Gender Equality

Women and girls comprise half of the planet’s population; their empowerment is essential in expanding economic growth and promoting social development in a sustainable way.

Gender inequality remains an everyday reality for the world’s women and girls. It can begin right at the moment of birth and continue throughout the course of a woman’s life.

Despite critical advances over the course of recent history, women in all countries and across all socioeconomic levels in society can face various forms of unfair treatment, including discrimination, harassment, domestic violence and sexual abuse. Other forms of abuse that are particularly prevalent in certain countries or cultural contexts include forced marriage, honor killings, deprivation of education, denial of land and property rights, and lack of access to work and to health care.

An estimated 1 out of every 3 women worldwide has experienced sexual or physical violence at home, in her community, and/or in the workplace.

Women may experience human rights abuses at different points in their working lives, including during recruitment, hiring, promotion and termination processes, as well as in daily interactions with colleagues and supervisors.

Outside of the workplace, women are often particularly vulnerable to the social and environmental impacts of business activities. For example, in many developing countries, women and girls are primarily responsible for fetching and hauling water. When company operations contaminate local sources, it is they who carry the burden of walking, often for hours, to the nearest substitute, which can prevent them from working or going to school.

According to the UN Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women (UN Women), gender “refers to the social attributes and opportunities associated with being male and female and the relationships between women and men and girls and boys, as well as the relations between women and those between men. These attributes, opportunities and relationships are socially constructed and are learned through socialization processes.”

Furthermore, gender equality “refers to the equal rights, responsibilities and opportunities of women and men and girls and boys. Equality does not mean that women and men will become the same but that women’s and men’s rights, responsibilities and opportunities will not depend on whether they are born male or female.”

Globally, working women still earn 24% less than men on average.

Women and girls comprise half of the planet’s population; their empowerment is essential in expanding economic growth and promoting social development in a sustainable way. In many cases, the full participation of women in the workforce would add double-digit percentage points to national growth rates. Evidence from around the world shows that gender equality advancements have a ripple effect on all areas of sustainable development, from reducing poverty, hunger and even carbon emissions to enhancing the health, well-being and education of entire families, communities and countries. In fact, “[e]quality between women and men is seen both as a human rights issue and as a precondition for, and indicator of, sustainable people-centered development.”

Globally, working women still earn 24% less than men on average.

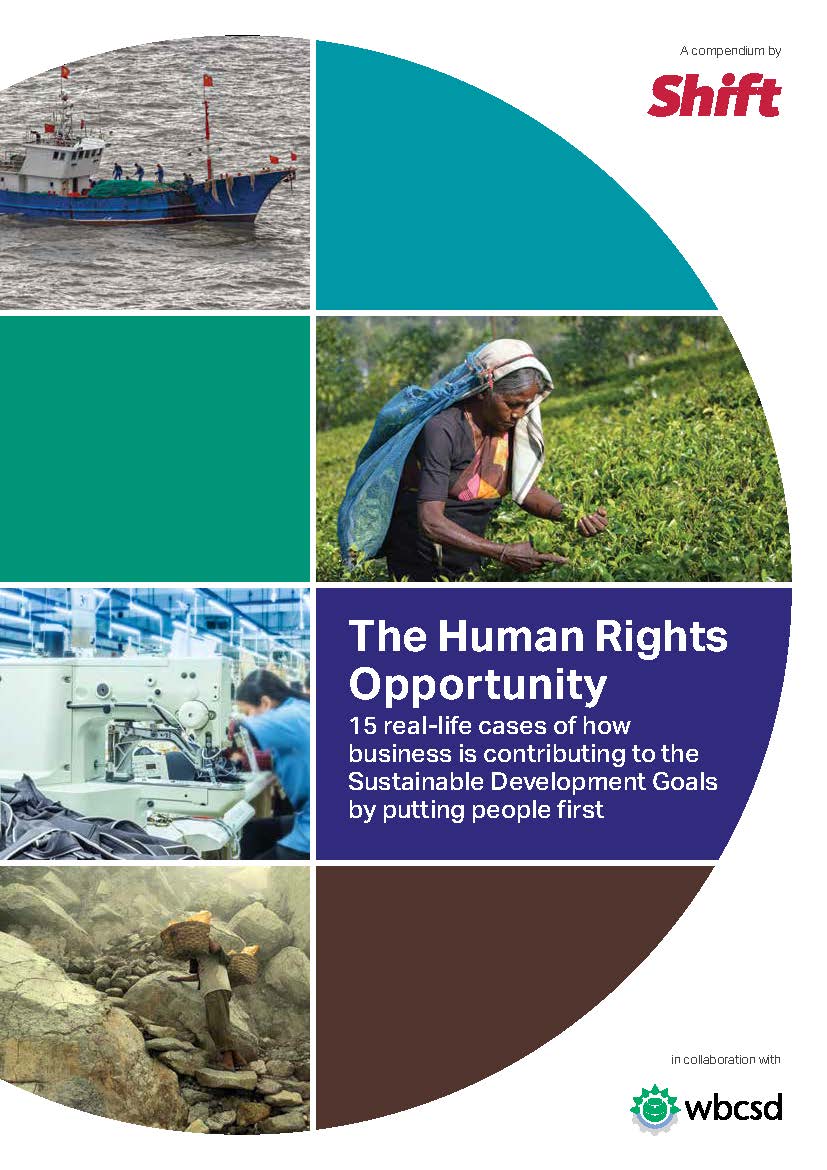

As illustrated in the figure above, and depending on the specifics of the relevant corporate initiative, addressing gender-related impacts in connection with business may contribute to the achievement of an array of the Global Goals, including:

- Goal 1: End poverty in all its forms everywhere [v]

- Goal 2: End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture [vi]

- Goal 3: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages [vii]

- Goal 4: Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all [viii]

- Goal 5: Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls [ix]

- Goal 6: Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all [x]

- Goal 8: Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all [xi]

- Goal 10: Reduce inequality within and among countries [xii]

- Goal 11: Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable [xiii]

- Goal 13: Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts [xiv]

- Goal 16: Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels [xv]

So, how are companies currently supporting a world in which these goals can become a reality – a world in which the rights of women and girls are respected across all areas of business activity?

Examples illustrated by the case studies below include:

- An individual clothing brand is piloting a peer educator training program: A global apparel company is aiming to address issues around women’s health and equality in the workplace via peer-to-peer training, sensitization among senior management, and accessible complaint channels at the factory level.

- Actors along a global value chain are collectively addressing the human rights impacts associated with a specific product: The largest supermarkets in the United Kingdom are working together on a product-specific project that engages importers and local civil society groups, government actors, exporters, farmers and workers to promote decent work for strawberry pickers in Morocco who are women.

- Brands are playing a key role in a worker-driven social impact program that uses market enforcement mechanisms to drive positive change: The agricultural industry in the United States is seeing real transformation in the lives of women farmworkers who too often face gender discrimination and sexual abuse in the fields.

The case studies explore each of these innovative and evolving models in more detail. Each case study captures publicly available information on the initiative, alongside experiences and opinions from various actors involved.

These summaries do not claim to give a definitive account of a specific initiative or of all perspectives on that case study; instead, they are intended to serve as illustrative examples of how action toward corporate respect for human rights can make a critical contribution to the achievement of various goals and targets under the SDGs.

Key Takeaways on Gender Equality

Individual Company Action

Individual Company Action

- Many human rights risks and impacts associated with women’s rights are intersectional, meaning that they do not exist separately from one another but are complexly interwoven. As such, gender issues may most effectively be addressed through holistic and coordinated approaches that recognize and link related issues (such as health, socioeconomic status, education, race, etc.) in activities and outreach.

- Programs that equip affected women to raise awareness themselves and provide resources to their peers may be an empowering means of expanding the scope, sustainability and accessibility of such programs.

- Buy-in from suppliers and behavior changes at the management level are key in enhancing the long-term impacts of initiatives that may be initiated by global brands but require sustained commitments from suppliers.

- Strategic partnerships with technical experts and peer companies within a sourcing country are instrumental in addressing systemic issues affecting women.

- Increased representation of women within worker committees and at all levels of a company may be essential in accurately reflecting gender-related risks and building the trust necessary to capture and address impacts.

Collective Action

Collective Action

- Economic empowerment and social security are integral to reducing negative business impacts on the human rights of women and maximizing outcomes for sustainable development.

- All actors along a global value chain can use and build their leverage in unique ways to facilitate change at the international, national and local levels.

- Collaborative efforts across a specific sector can inspire and equip affected women to collaborate and organize among themselves, potentially contributing to longer term advancements in addressing risks and impacts.

- Worker-driven standard-setting and feedback loops can capture risks and impacts in a way that traditional social policies and audit systems might not.

- Market enforcement mechanisms are instrumental in driving real change on the ground and can be embedded in initiatives in ways that both ensure accountability and create benefits for all actors involved.

Inditex’s Sakhi Health and Gender Equity Project

Implementing worker-centric strategies through peer educator programs

The challenge

There are more than 1.5 million workers in Inditex’s supply chain, and the overwhelming majority of them are women. As such, a key objective of the global apparel brand is to “promote gender equality and women’s empowerment” across the company’s own staff and throughout its supply chain.

In India, women comprise up to 80% of the workforce in the factories that Inditex sources from. Most of these women are from rural areas with limited economic and educational opportunities. Human rights risks are particularly severe when it comes to their health and well-being. For instance, factory facilities may not be equipped to accommodate the reproductive health needs of women workers; and instances of harassment, abuse and discrimination inside and within the vicinity of factories may run high.

“The textile industry is a mainstay of the economy in many of the countries where we operate and women occupy most of the jobs in all stages of production. For this reason, Inditex’s supply chain is mostly female. And it is our duty and mission to contribute to all these workers having the best working conditions and enjoying the same opportunities as a man.”

Inditex Annual Report 2016

The response

Inditex recognized these widespread challenges in its Indian supply chain and thus launched the Sakhi Health and Gender Equity Project in 2016 with the dual objectives of addressing women’s health risks in the workplace and preventing harassment or abuse.

The project is carried out in partnership with St. John’s National Academy of Health Services (Bangalore) and the Swasti Health Catalyst. The pilot phase of the program has so far been initiated at six factories within Inditex’s supply chain in India, covering a total of 4,290 workers to date.

Key aspects of the initiative

Named after the Hindi word for “female friend,” the Sakhi project centers on a peer educator training program where senior women workers are trained to raise awareness at the factory level and educate their colleagues in the areas of health and gender equity.

“I know that these women [peer educators] will help another ten more, and that ten will help another ten more. So, I think this whole idea of creating awareness is cascading into something which is much bigger and not just restricted to this industry.”

– DR. DEEPTHI SHANBHAG, ST. JOHN’S MEDICAL COLLEGE

The Sakhi Health component of the project is carried out with St. John’s National Academy of Health Services (Bangalore) in the following ways:

- Awareness raising and sensitization workshops with workers, supervisors and factory management in the areas of reproductive and maternal health, nutrition, hygiene, HIV/AIDS, ergonomics and access to local health care services.

“The majority of workers at the factory level in the garment industry in South India are women; and many of them are coming from rural areas with very little information about their health and how to access basic health services. This is a risk for a company like Inditex that is sourcing from factories situated in South India. They have recognized this and are trying to skill up both workers and management through the peer educator program, which is periodically assessed and adapted.”

Dr. Naveen Ramesh, St. Johns Medical College

According to Inditex:

- Two factories have initiated these programs so far, covering 740 workers.

- Going forward, the project aims to bring together factory-level peer educators at periodic conferences to discuss challenges, share good practices and explore collective solutions.

The Sakhi Gender Equity component of the project is carried out with the Swasti Health Catalyst in the following ways:

- Sensitization training of top management and production heads in 100% of Inditex’s suppliers in India in an effort to raise awareness of gender equality issues primarily among men in senior management at the manufacturing level.

“We want to make sure that management at the supplier level is accountable for the successful running of these programs. It has to be a supplier run and owned project for the solutions to be sustainable and we are thankfully seeing this happen as suppliers are more and more building, on their own, the activities of the Sakhi project into their production calendars going forward.”

– CHRISTIAN CHANDRAN, INDITEX

- A collaborative study with other brands working in India to identify and analyze worker needs. The study aims to advance worker well-being, better understand the challenges faced by migrant workers, and address issues related to gender-based violence, harassment and discrimination as a means of better informing factory-level programs.

- Development of an anti-discrimination and anti-harassment guide with Swasti Health Catalyst based on consultations with suppliers and anonymous surveys of workers, supervisors, and management.

“We aim to find and implement solutions together with companies. There’s a way to achieve business objectives without compromising on values and human rights, and we’re trying to support businesses like Inditex in first understanding these issues accurately and then taking action in an informed way.”

Joseph Julian K.G. and Shankar A G, Swasti Health Catalyst

- Strengthened systems to address sexual harassment grievances in factories by establishing policies and carrying out capacity building for management and members of worker committees.

- Creation of Social Protection help desks at the factory level where workers can more easily access social protection resources and services.

- 4 factories have initiated these programs so far, covering 3,550 workers.

- 36 employment agencies and 327 peer educators have been trained in the prevention of gender-based abuse in employment practices.

“Our Sakhi related work is not just a project. It’s a movement, and it’s creating change both inside and outside of factories. We’re aiming to achieve this positive change toward gender equality and worker health in a culturally aware, progressive way by adding new dimensions every year and committing to the long-term work of changing mindsets and – most importantly – behaviors.”

– MAYANK KAUSHIK, INDITEX

Better Strawberries Group

Enhancing women’s social security and economic empowerment

The challenge

At the break of dawn, thousands of women across the Larache province in northern Morocco pack into vans and travel long distances along rough roads to strawberry fields. There, they pick strawberries for eight hours or more, often for less than minimum wage and without the social security protections offered at the national level. They may never interact with farm owners and instead deal only with labor intermediaries (waqqaf) regarding recruitment, negotiation of wages, transportation, supervision and payment. They may face sexual harassment and verbal abuse from their supervisors who are mostly men. And some do not have protective gear to safeguard their health from the heavy use of pesticides in the berry industry nor regular access to hygienic toilets and clean water throughout their work days.

Morocco is one of the largest exporters of strawberries in the world; and the berry business is a key player in the Moroccan government’s national development plans. Field workers in this burgeoning industry are overwhelmingly women; an estimated 20,000 women are brought into strawberry jobs each year. While this growth has brought significant working opportunities for women in Morocco, it has also created mounting pressure on growers to rapidly hire for these labor-intensive positions without sufficient attention to, or concern for, putting decent working conditions in place.

“Morocco’s female strawberry pickers, in many cases, could possibly be regarded as a real and classic example of women’s low-paid labour facilitating greater profits for others … [W]hile the sector has been growing significantly and contributing to positive economic results, unfortunately working conditions within the supply chain have evolved in a ‘predominantly informal and precarious environment.’”

Sian Jones, Oxfam

The response

In 2011, after Oxfam began to highlight the increasingly precarious situation of women workers in the Moroccan strawberry industry, the Ethical Trading Initiative (ETI) and Oxfam brought together most of the United Kingdom’s major supermarkets (including Marks & Spencer’s, Tesco and Sainbury’s) and berry importers to develop a plan of action regarding the issue. Termed the Better Strawberries Group, the initiative has thus far focused on the United Kingdom as one of the largest importers of fresh Moroccan strawberries. It has increasingly engaged with retailers and brands in France, Spain and Sweden as well.

“Most of the major retailers in the UK are ETI members and already working with key suppliers, so it made sense to build on these established relationships to try and address the issues faced by these women workers in Morocco. It’s important to look at all of the actors involved in these global supply chains, facilitating collaboration and momentum at the international level while engaging the government as well as producers, civil society and workers directly in Morocco.”

– SLOANE HAMILTON, OXFAM

Shortly after the formation of the Better Strawberries Group, a stakeholder meeting was held in Morocco in 2012 where the British importers and supermarkets involved began the process of engaging Moroccan berry growers, their key associations, and civil society groups to further outline a collective 2012-2015 action plan.

“You buyers put pressure on quality with the products. You can also put pressure on the quality of the conditions for workers. Strawberry farm owners listen to you.”

Woman worker in the Moroccan strawberry industry

A unique analytical tool called SenseMaker was used in 2016 to capture the stories and insights of women workers in a way that empowered them, rather than demeaning or re-vicitimizing them. The open-ended “micro-narratives” shared by the workers through this methodology and the nuanced quantitative data captured alongside it have informed and supported the program.

Key aspects of the initiative

The Better Strawberries Group and its affiliated programs have a distinct focus on improving the working conditions of strawberry pickers in Morocco who are women and the provision of social security services at the local level. Its activities and results to date are centered on the following three components:

- Campaign: In partnership with the National Social Security Fund (CNSS) in Morocco and local civil society coalitions, the initiative set up “caravan” tents near work sites, transport spots and villages to facilitate the formalization of strawberry pickers’ work. This involved assisting the women in obtaining national identification cards that allow them to sign formal work contracts, register for social security entitlements, and access free health care services. Producers were also increasingly registered with CNSS as part of the program to aid the Moroccan government in the enforcement of employer contributions to social security programs, as well as minimum wage and minimum age laws. Women with two children may receive up to 40% more income due to government contributions as part of the CNSS program.

- Approximately 16,100 women workers were reached as of 2014.

- More than 1,400 women received national identification cards.

- Over the course of the project, 14,027 individuals, including 9,205 women, received CNSS cards or verified existing cards.

- The number of people registered with CNSS in the Larache province increased by 40% in 2012 and 70% in 2013.

- The registration of workers with CNSS sits around 65% for the Larache province.

- The Moroccan government has provided support staff for the registration caravans.

- Employers have reported increased productivity and more stable workforces.

- Observatory: Each campaign caravan also houses an “observatory” where local civil society organizations raise awareness of labor rights in Morocco, detect and collect labor rights violation cases, provide guidance and resources to the workers, and record instances for further processing. In 2016, the observatory collected 362 rights violation cases.

- Training on the Moroccan labor code and appropriate worker relations took place with 17 producers.

- Agricultural transporters formed their own association; and sensitization training on safe and humane practices was carried out with government representatives.

- Association of women workers: With support from the Better Strawberries Group, women workers came together to form their own workers association, called “Al Karama,” which means “dignity” in Arabic. The group has been an active part of the various components of the program, liaising with the campaign caravans, carrying out labor rights training and awareness raising, collectively demanding safer transport and decent working conditions, and providing referrals to workers when they report specific issues. A second association, named “Al Amal,” was created in 2013 to ensure women workers’ representation among local authorities and local growers, helping to reduce women’s vulnerability by providing a direct link between workers.

“[The women workers] have acquired a legitimacy that now allows them to organize activities independently, thereby further strengthening the social fabric among those involved.”

– 2014 OXFAM REPORT

The Better Strawberries Group has met regularly in London to discuss progress and challenges. Annual meetings take place in Morocco among the various stakeholders involved. Growers involved in the program have also joined a “Producers Platform” hosted by Oxfam to meet and discuss challenges and successes. They are in the process of developing a Code of Conduct that is drawn from the ETI’s base code.

Fair Food Program

Taking worker-driven standards and enforcement mechanisms to scale

The challenge

The #MeToo and Time’s Up movements continue to make headlines around the world every day. As these and other campaign efforts have made clear over many decades, some level of gender discrimination, sexual harassment, abuse and/or violence in the workplace is pervasive across industries and geographies.

The agriculture sector in the United States is no exception. In fact, women farmworkers face some of the worst gender inequality conditions in the country – it is estimated that 80% of farmworkers who are women are sexually harassed or assaulted in the course of their work.

“[Sexual harassment] is the dark underbelly of American agriculture.”John Esformes, Pacific Tomato Growers“Women are routinely – routinely – sexually harassed or assaulted in the fields.”

Greg Asbed, Coalition of Immokalee Workers, Co-Founder of the Fair Food Program

On farms and in fields across the country, women farmworkers are often verbally or physically abused by supervisors or managers, frequently under threat of losing their jobs or the ability to work in the United States if they resist or report being raped, groped, grabbed, harassed, demeaned, discriminated against, or exposed to other such behaviors.

Moreover, “[w]omen farmworkers, just as their male counterparts, in fact suffer a wide range of degradations, including sub-standard wages, wage theft, physical and verbal abuse, gender and racial/ethnic discrimination, and high injury and fatality rates.”

The response

The Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW), built on a foundation of farmworker community organizing in Florida since 1993, established the Fair Food Program (FFP) in 2011.

CIW, farmworkers on participating farms, farmers and retail food companies implement the FFP. The Fair Food Standards Council (FFSC) is the program’s independent monitoring body and the only dedicated third party oversight organization of its kind for agriculture in the United States.

The FFP “harnesses the power of consumer demand to give farmworkers a voice in the decisions that affect their lives, and to eliminate the longstanding abuses that have plagued agriculture for generations,” including sexual harassment, violence, discrimination and abuse.

“The Fair Food Program is tackling gender-based violence and harassment alongside sub-poverty wages, forced labor, access to remedy, and many other human rights-related issues that have afflicted this industry in the past.”

– STEVEN HITOV, COALITION OF IMMOKALEE WORKERS

The FFP currently boasts 14 participating buyers, including Yum Brands (which includes Taco Bell), Walmart, Chipotle, Trader Joe’s, Subway, Whole Foods, Burger King, and McDonald’s. Growers of 90% of Florida’s tomato production have signed on to the program. The FFP also involves strawberry and bell pepper farmers in Florida, as well as tomato growers across Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Virginia, Maryland and New Jersey. In mid-2018, the FFP will be expanding into other crops in Texas.

Key aspects of the initiative

The components of the FFP make up what is called the “Worker-driven Social Responsibility” (WSR) model. The key FFP mechanisms and relevant data to date include:

- Legally binding Fair Food Agreements between participating buyers and CIW: These agreements require the buyer to contribute to the Fair Food Premium aspect of the program, outlined below. They also provide market enforcement provisions to uphold the Fair Food Code of Conduct, which goes beyond legal compliance to set a more robust industry standard around sexual harassment and abuse, as well as issues such as forced labor, child labor, wage theft, working hours, direct employment and decent working conditions, including shade tents, clean drinking water, regular bathroom breaks, safe transportation and an end to forced overfilling of buckets, which contributes to underpaying workers while adding to the physical strain of farm work.

“[The FFP] ends up being a win-win-win proposition. Farmworkers’ lives are improved – immeasurably – every day. The growers individually become better operations, with less risk. And buyers no longer have to worry about the possibility of another case coming out.We’re taking a business approach to human rights that is worker-driven and based on the principle that companies need to use their market power to improve people’s lives.

Our ‘Worker-driven Social Responsibility’ (WSR) model works, and it can be replicated across other industries and geographies if more and more businesses get involved. The WSR Network is supporting these efforts, spreading the model to other areas in the United States, such as with the Milk with Dignity program in Vermont, and even overseas, feeding into the Bangladesh Accord and tackling workers’ rights issues in the seafood industry in Southeast Asia.”

– GREG ASBED, COALITION OF IMMOKALEE WORKERS, CO-FOUNDER OF THE FAIR FOOD PROGRAM

- Fair Food Premiums: Outlined within the Fair Food Agreements, this mechanism commits participating buyers to pay a “penny per pound” premium on top of the regular price paid for tomatoes or other covered products. The premium is then passed through by farmers as a bonus on worker’s paychecks, which are monitored by the FFSC. This component of the FFP has been lauded as an innovative living wage initiative that recognizes that “workers who worry about putting the next meal on their family’s table are often too constrained by fear to be effective monitors and defenders of [their own] rights,” including those relating to gender equality. Since the FFP’s inception, over US$26 million have been added to farmworkers’ payrolls.

- Worker education: At the time of hire and throughout the growing season, each farmworker covered by the FFP receives training on the Fair Food Code of Conduct, including its zero tolerance policies on forced labor, child labor, sexual violence and abuse in the workplace. The CIW Worker Education Committee, which is comprised of farmworkers themselves, conducts worker-to-worker training that takes place on company time and with a company representative present to demonstrate support from the employer. To date, over 220,000 workers have received “Know Your Rights and Responsibility” materials (available in English, Spanish and Haitian Creole). CIW has educated nearly 52,000 workers face-to-face.

- Independent audits: Conducted by the FFSC, the independent and sometimes unannounced FFP audits involve extensive and ongoing document review and interviews with all levels of a farm’s management, from the boardroom to the field. Moreover, worker interviews take place with 50% or more of the workforce on any given farm, due in large part to auditors’ efforts to reach workers both in the fields and offsite, as auditors visit housing camps, ride buses and make themselves present at transport spots. Importantly, supervisors are not present when onsite interviews are conducted to ensure openness of workers in sharing challenges or concerns. Audit reports are then provided to the grower and to CIW. Over 20,000 workers have been interviewed as part of the FFP audit program. As of October 2017, the program has redressed 6,839 audit findings of non-compliance.

- Complaint resolution mechanism: In recognition that even unannounced audits are only a snapshot in time and acknowledging the right to remedy when human rights violations occur, the FFP includes a confidential complaints system that is independently run by the FFSC. This system centers on a toll-free, bilingual complaint line that FFSC investigators who know the relevant farms answer 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. The hotline information informs subsequent audit interviews and worker education programs. Since its start and covering around seven growing seasons so far, the program has resolved more than 2,000 complaints. Most complaints are resolved in less than two weeks and the vast majority in less than a month.

“We’ve received complaints and testimonies of hostile work environments, of supervisors asking for sexual favors in return for ensuring that this woman keeps her job. We’ve made sure that workers know that there are different avenues that they can take to make a complaint so that there isn’t any more sexual harassment in the fields.”

Lupita Aguila Arteaga, Fair Food Standards Council

When a complaint is submitted to the hotline, the FFSC investigates the situation either alone or in collaboration with the relevant grower, depending on the specifics of the situation, and then develops a corrective action plan for implementation by the farmer with support from FFSC. Whenever possible, resolutions of complaints are made known to the other workers to demonstrate a lack of retaliation for bringing complaints and to reconfirm the grower’s commitment to the program. The FFSC maintains a detailed database of complaints and corrective actions taken; an appeals mechanism is built into the system.

“In the instant information age, each brand is just one click away from being in the headlines for human rights violations. We’re holding the mirrors up to prevent the risk before it blows up in companies’ faces.In sexual assault and other cases, we’ve seen each mechanism of this program kicking in and working the way they’re supposed to. Only a program like this can give brands reassurance while at the same time ensuring the protection of workers that come forward with issues and early warnings. The headlines for the Florida tomato fields used to be ‘assault and slavery.’ Now, the industry is known as ‘the best work environment for agricultural workers in the entire United States.’”

– JUDGE LAURA SAFER ESPINOZA, FAIR FOOD STANDARDS COUNCIL

- Market enforcement: In the event that a serious violation of the Fair Food Code of Conduct arises at the farm level via any of the above mechanisms, the participating grower must remedy the situation. If the grower fails to do so, it is suspended from the FFP and the participating brands will therefore no longer buy from that supplier until it gains reentry to the FFP. This “real market” incentive within the FFP is a key contributor to the fact that sexual harassment and abuse are now the exception, rather than the rule, throughout the Florida tomato industry and in the additional farms covered by the program.According to the FFSC, “These measures have brought an end to impunity for sexual violence and other forms of sexual harassment at Fair Food Program farms, where there have been zero cases of rape or attempted rape since the implementation of FFP standards in Season One. Cases of sexual harassment by supervisors with any type of physical contact have been virtually eliminated, with only one such case found since 2013.”

“The work that [the FFP] does makes you feel that you are not so alone in this country. I think many women now have more courage to speak and not remain silent.”

AMALIA MEJIA DIAZ, FORMER FARMWORKER WHO FFSC HELPED WITH A SEXUAL ASSAULT CASE