In 2018, our work on the Valuing Respect project made one thing clear: better evaluation of business respect for human rights starts with reconnecting to what we are trying to achieve in the world.

That is, to remember that corporate policies, systems and programs have always been the means, not the ends, of the responsible business agenda. As we continue our research in 2019, we are field testing a new approach by asking investors, civil society and businesses to step out of their comfort zones and question their assumptions using the beta version of our first Valuing Respect tool.

Valuing Respect Project Lead Mark Hodge facilitating a consult in Singapore

Image courtesy ASEAN CSR Network

Looking Back

2018 was a fascinating year. We engaged with hundreds of people from business, civil society, government and the investment community, and held consultations in Europe, South-East Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa and North America. In parallel, we conducted empirical research to understand why the way we measure corporate human rights performance isn’t working. For example, we came to realize that 70% of the 400+ “S” indicators used across the major ESG tools, focus on policy commitments, inputs, and activities, not on actual results.

In sum, we confirmed our main hypothesis: when testing the effectiveness of a company’s process or program, most people jump straight to measurement. They develop indicators, agree on metrics and start collecting data. This certainly offers more information about what is happening. For example, data can tell us which companies are making policy commitments, the general scale and location of forced or child labor in a supply chain, the number and nature of local community grievances at a mining location, or even the views of workers on their workplace realities.

But measurement and monitoring alone do not help us to understand why and how things are happening, nor whether the things we measure are a sign that we are achieving desired outcomes. We end up flooded with information, but with no rigorous way of making sense of it. As one participant in our New York consultation noted, we end up “counting without context”. We have more knowledge, but not always more wisdom.

A New Logic

2018 helped us see the problem, but it also got us thinking about what a better approach looks like. After much thought–and hundreds of hours of consultation– we came up with an interesting proposition: what if we looked at measurement using a theory of change (TOC) model?

TOC forces a focus on outcomes for the specific people affected by business activities. It also offers an additional component: building the connection between risk to people and risk to business.

We realized that a TOC model offers an interesting new perspective. It moves away from ‘measuring for the sake of measuring’, and demands that we think systematically and robustly about the necessary requirements and conditions to achieve a desired outcome. It also provides a way for companies and their stakeholders to develop indicators with reference to the outcomes they want to attain, the means by which they are trying to achieve them, and the assumptions their approach depends upon.

Theory of change models are often developed in the fields of international development and public policy, where they tend to include the same core elements: inputs, activities, outputs, outcomes and impacts, based on a cause and effect sequence. In the Valuing Respect project, we have adapted the model to fit the particularities of evaluating business respect for human rights.

Whereas other models focus on a broader and more remote societal impact, which may hide negative impacts on the most vulnerable groups through appeal to overall social benefit, TOC forces a focus on outcomes for the specific people affected by business activities. It also offers an additional component: building the connection between risk to people and risk to business.

Perhaps the most important adaptation we made to the model is adding a deliberate focus on ‘practices and behaviors’ between ‘outputs’ and ‘outcomes’. That is, to look beyond activities and their immediate outputs, and to focus on the desired changes in human behavior (and thus, in outcomes for people. )

We need to go from ‘it makes sense’ to, ‘it makes a difference’.

This changes the measurement paradigm. Rather than ticking boxes and counting actions, the TOC model tells us whether our approach to solving issues is resulting in positive outcomes. Whether, for example, audits, trainings, or policies are leading to better working conditions. Once a clear and replicable connection between certain practices/behaviors and outcomes is established, the former can become valuable indicators of the latter, as they can be more easily measured over time and at scale.

Field Testing

We know this makes sense in theory, but now we need to see it in action. We need to go from ‘it makes sense’ to ‘it makes a difference’. That is why, in 2019, we are working with companies and their stakeholders to field-test the beta version of our Theory of Change tool.

The tool aims to provide a simple step-by-step method for companies and their stakeholders to develop and work with indicators in ways that support learning about what is working and why, in relation to their specific objectives for advancing business respect for human rights. We will be testing it with practitioners both in the design phase of new interventions, and to evaluate and improve existing interventions. We will consider how to apply it to action taken by companies individually, as well as with industry peers or via multi-stakeholder initiatives.

We’ll be sharing insights from practitioners on lessons learned, and how they affect decision making and resource allocation in favor of measures that deliver tangible outcomes for workers, consumers, and communities.

In early 2020, we will publish these insights along with the tested and refined methodology and supporting resources.

But wait! Don’t corporate policies, governance arrangements and business processes matter?

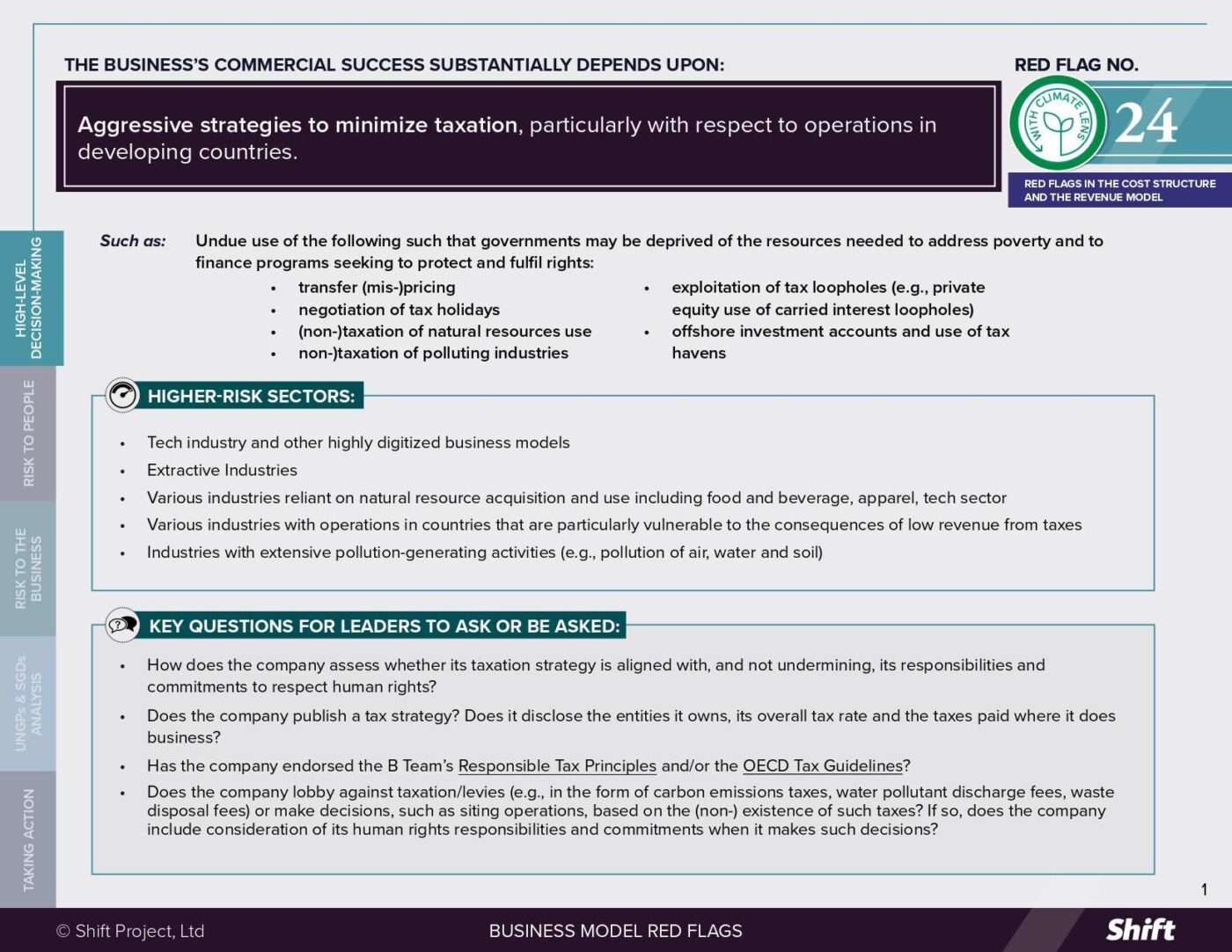

Yes, but with a twist. We’ll address this in the Valuing Respect project and our work on business-model red flags, leadership and governance indicators, and quality of business processes.

By Mark Hodge

By Mark Hodge