These remarks were originally delivered by Shift’s President Caroline Rees at the Expert Conference on Sustainable Supply Chains on February 21st, 2019 in Berlin.

I’m grateful for the invitation to join you today for a conversation that is both important and timely, looking at the distinct roles and responsibilities of business and governments when it comes to sustainable supply chains, and the rights-respecting business practices on which they depend.

In sharing with you a few reflections this morning, I’d like to start by taking us back briefly to the reason why it was, and is, so important to understand the distinct roles of business and government; and to remind us why this conversation has never been more central to the challenges of our time.

And then I’ll share with you a few reflections about what the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights mean when they call for a ‘smart mix’ of government measures, and what that might imply for your own deliberations here in Germany.

First, let me take us back a few years.

Before John Ruggie’s mandate was created, I was representing the UK Government at the then UN Commission on Human Rights – just before it became today’s Human Rights Council.

That was 2004, and the idea that companies have a responsibility with regard to people’s human rights was hotly disputed.

- Many in the business arena felt that claims of such a responsibility were merely an excuse to push onto business the obligations of states.

- And many in civil society saw a conveyer belt of severe business impacts on people that were treated as if business had no responsibility at all.

Little surprise that discussions were heated!

And little surprise that as we negotiated the mandate for a new role of Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General on Business and Human Rights – which Kofi Annan then invited John Ruggie to take on – the task of identifying the distinct roles and responsibilities of governments and business was front and center.

Fast forward to 2011, and of course the UN Human Rights Council endorsed the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights that John had developed over six years of research and consultation, and which were built on three distinct pillars:

- The duty of states to protect human rights against abuse by third parties, including business;

- The responsibility of business to respect human rights

– meaning to avoid infringing on people’s human rights through their

operations and value chains, and address any impacts that do;

- And the need for anyone whose human rights are harmed by business to have access to remedy through effective judicial and non-judicial mechanisms – which reflects responsibilities of both states and business.

Let me highlight two critical points from the UN Guiding Principles:

- First, the corporate responsibility to respect human rights

is not an optional extra, or a sign-up proposition – it is a baseline

expectation for all companies, everywhere. This is no longer about voluntarism.

- Second, the responsibility of business does not increase or decrease depending on what governments do. It remains the same. But it is considerably harder to implement the responsibility to respect human rights where governments fail to meet their own duties.

That brings us to the heart of our discussion today: what can and should governments do? What constitutes what the Guiding Principles call a ‘smart mix’ of measures on the part of governments in meeting their own duty to protect?

Before I say more about the idea of a ‘smart mix’, it’s important to understand this conversation about business and human rights in context.

Because of the way the discussion on business and human rights emerged onto the international stage, it can sometimes appear to be a bit of a niche topic, a side-show, or perhaps a small sub-set of what the investment arena refers to as ‘ESG’ – environmental, social and governance factors.

The question of business respect for human rights lies at the heart of one of the most pressing challenges of our time: gross inequality.

It is none of the above. Quite the opposite: the question of business respect for human rights lies at the heart of one of the most pressing challenges of our time: gross inequality. As such, it needs to be approached with the same seriousness, attention and resources as is the role of business impacts on the environment in the context of our other most pressing challenge: climate change.

Let me pause on that for a moment.

A critical turning point in the discussion of climate change and the role of business came when climate change was understood as a tragedy of the commons.

What does that mean?

- It means that we realized our planet and the environment it provides

us with is a precious shared resource system on which we all depend;

- and if companies and others draw down on this resource individually for their own narrow self-interest, collectively they erode the very resource on which we all – business included – depend.

There is an analogous kind of tragedy of the commons in the gross inequalities that now characterize societies in so many countries – including developed and emerging market economies – and the backlash against globalization that this has engendered.

Why is this a tragedy of the commons?

Well, we have another shared resource system on which we all depend to survive and thrive – namely, social cohesion and stability.

This relies in good part on advancing human dignity, equality, hope and opportunity: the sense that people of all backgrounds can better their lot and build a brighter future for their children.

Yet business practices have too often drawn down on human welfare for narrow, profit-focused self-interest, squeezing out dignity and opportunity for so many in a process of globalization that has failed to protect the most vulnerable in our societies.

We have seen this in moves to seek out ever lower-paid workers around the world, in land acquisitions and permits that have dispossessed rural communities without consultation or due compensation, in the over-excited embrace of a gig economy that commoditizes people’s labor and the exploitation of people’s data that commoditizes their very identities.

And so social cohesion and stability – this shared resource system – has been gradually depleted, to the point where the resulting tensions and anger – exploited by some for political ends – tear our societies apart and make obvious what we should have known all along: that ultimately, we all lose.

This is the story of business and human rights.

And this is why it is no side show, but must be center stage in any search for solutions to the challenges of our time.

As with climate change, it reinforces why we need urgent action by both business and government – separately and collaboratively with each other and with civil society – to address gross inequalities and the human rights impacts that cause and result from them.

A smart mix.

As we look, then, at the role of governments, this is where a ‘smart mix’ of interventions comes in.

When the Guiding Principles speak about the need for governments to adopt a ‘smart mix’ of measures, the word ‘mix’ should be understood to be as important as the word ‘smart’.

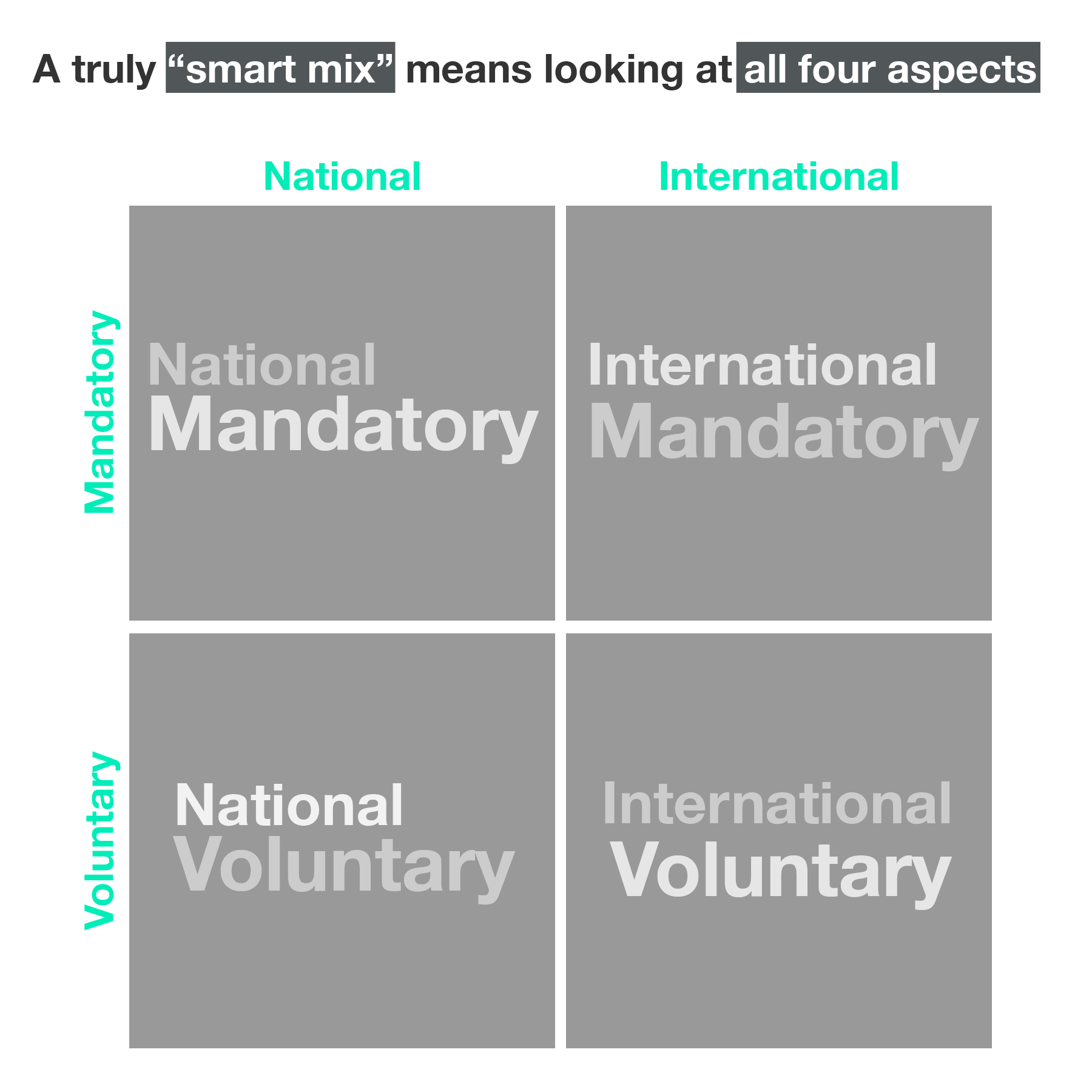

The commentary to UN Guiding Principle 3 states that, “States should not assume that businesses invariably prefer, or benefit from, State inaction, and they should consider a smart mix of measures – national and international, mandatory and voluntary – to foster business respect for human rights.

As we explore today what we might, from all our different perspectives, consider more or less ‘smart’ measures, let’s not forget that this is equally about a ‘mix’: comprising measures across all those categories of ‘national and international’ and ‘mandatory and voluntary’.

Let’s consider five distinct kinds of role that governments can take as part of a smart mix, all of which are covered in the UNGPs. They include:

- policies and exhortation,

- guidance and support,

- integration in government’s own transactions with business,

- legislation or regulation, and

- ensuring access to remedy.

As we look at each of these measures, we see why a smart mix is essential, as no one of them can be effective without some or all of the others.

First, there is the role of policies and exhortation. UN Guiding Principle 2 makes clear that ‘States should set out clearly the expectation that all business enterprises domiciled in their territory and/or jurisdiction respect human rights throughout their operations.’

- This requires a clear and unambiguous assertion of what the government expects of business – right across their value chain. It should provide predictability and be coherent across all parts of the government.

- But a statement of expectation is quickly undermined if it is unsupported by other interventions.

- For example, if the government does not scrutinize whether the

companies it procures from, or to which it gives trade support, have

identified and addressed human rights risks, it will be quickly assumed

by businesses that they are not truly expected to do the same themselves.

- For example, if the government does not scrutinize whether the

companies it procures from, or to which it gives trade support, have

identified and addressed human rights risks, it will be quickly assumed

by businesses that they are not truly expected to do the same themselves.

- In sum, government policy that is undermined by government practices quickly becomes a non-policy.

Second, is the role of government in providing support and guidance to companies. We must be honest and clear-eyed in recognizing that implementation of respect for human rights is not straightforward. It take considerable time, commitment and effort. And the job is never done.

- So government has a critical role to play in assisting companies in

making progress – including through advice at home and through overseas

missions, and through guidance, resources and other forms of support.

- For example:

- The UK Equality and Human Rights Commission issued guidance to company boards on respect for human rights.

- A number of governments have played a critical role in initiating

and chairing the Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights – a

key international initiative including both business and civil society

members.

- The Dutch government commissioned an independent evaluation of human rights risks in the global supply chains of 13 sectors and has supported the development of binding agreements among stakeholders in those sectors.

- The UK Equality and Human Rights Commission issued guidance to company boards on respect for human rights.

- Yet guidance is just that – a resource one may choose to use. Those companies that do not see a need to make progress can and will ignore it.

- Progress will be limited if no evidence is required that indeed progress is being made.

- So again, we must think of other measures as well.

- Progress will be limited if no evidence is required that indeed progress is being made.

Raising expectations and demands alone is inadequate to help business on the journey of implementation.

Third is the role of government when it does business with business. The UNGPs call this the ‘state-business nexus’ and refer explicitly to activities such as procurement and the provision of export credit guarantees, investment insurance, development aid and development finance, as well as government actions in ownership or control of state-owned enterprises.

- The Norwegian export credit agency has long shown leadership in its

own human rights due diligence on clients and in action that has

leveraged positive change, and the agencies of Denmark, Sweden, the

Netherlands and Canada are also stepping up to their role in this

regard.

- The Finnish Government has perhaps shown unique coherence in

bringing together all five of its public finance instruments to evolve

their own implementation of human rights due diligence collectively and

in coordination.

- The US Federal Acquisition Regulation, which governs public

procurement in the US, prohibits child labor, forced labor and human

trafficking, and various Executive Orders have further expanded specific

human rights protections in the procurement context.

- Yet this kind of action by governments when they do business with business also requires support from other measures. Raising expectations and demands alone is inadequate to help business on the journey of implementation.

- The UK’s Development Finance Institution has developed due diligence

guidance and practical training for fund managers in the private equity

firms it invests in in high-risk markets.

- And the US General Services Administration also makes guidance to procurement officers in government public to assist them and their suppliers in meeting expectations.

- The UK’s Development Finance Institution has developed due diligence

guidance and practical training for fund managers in the private equity

firms it invests in in high-risk markets.

Fourth comes the role of legislation and regulation. Of course, legislation has always been a feature of business and human rights, even when not labeled as such. Typical examples include laws on health and safety, consumer protection, non-discrimination in the work place, freedom of association and data privacy.

We have seen a range of legislative initiatives in recent years, including on child labor and modern slavery in supply chains, on conflict minerals in supply chains, and on human rights reporting in the context of wider non-financial reporting

Recently, of course, we have seen a groundswell of support in various European states for mandatory human rights due diligence legislation.

- The French Duty of Vigilance law was a first example and will be discussed further today.

- The popular initiative that is under discussion in the Swiss legislature warrants close attention as showing some very thoughtful balances in requiring that companies demonstrate the adequacy of their due diligence when complaints are raised, but also allowing that where companies do so, this can also be a defense against liability.

- The 2016 revisions to the US Tariff Act of 1930 takes a similar approach to requiring the demonstration of adequate due diligence, in the specific case of forced labor.

- Anyone who has reason to believe that products produced by forced labor are being or likely to be imported to the US may report this to Customs and Border Protection for investigation.

- Products can then be withheld until documentation of due diligence for forced labor is provided by the company. A list of products being withheld or released is made public.

- Anyone who has reason to believe that products produced by forced labor are being or likely to be imported to the US may report this to Customs and Border Protection for investigation.

Let me highlight three of the benefits we see that can flow from robust and workable human rights due diligence legislation:

- It can elevate the examination of human rights risk to senior levels of the company and the board, as well as mainstreaming it into business functions that otherwise too often see it as a diversion and distraction;

- It can level the playing field for companies. This

helps ensure that it is not only those companies with brand names or

other forms of public exposure that are pressured to improve. It also

avoids the current danger that companies that are de facto leaders are

more critiqued than those who may have done little or nothing but manage

to fly below the radar of attention.

- It can provide a means for people who have been harmed by business activities to find an avenue for remedy, where it includes civil liability for companies. Since these are often the most vulnerable people in societies around the world, the importance of these all-too-rare means for them to access remedy cannot be overstated.

Of course, legislation can also be poorly crafted. That leads not just to inefficiencies and frustration, but can also have perverse consequences – including for human rights. Let me highlight three particular risks.

Respect for human rights is not simply a compliance proposition. It fails if and when it is treated as such.

- First, the desire for clarity can quickly lead to a tick-box, compliance-led approach to the drafting of legislation.

- But respect for human rights is not simply a compliance proposition. It fails if and when it is treated as such.

- Rather, it is a way of thinking about business decisions and action,

a way of considering the implications of what the company does for

people inside and outside the company.

- Respect for human rights is fundamentally about culture and

behavior. And for that, tick-box lists and mechanical approaches are

insufficient.

- But we can look to various other fields, from health and safety to consumer protection to find lessons in how to avoid this pitfall.

- But respect for human rights is not simply a compliance proposition. It fails if and when it is treated as such.

- That raises a second point, which is that it is important to strike a careful balance in how precisely laws prescribe what is asked of companies.

- Laws that are too prescriptive risk being inappropriate to the actual operating realities of many companies, and can distort practices in unhelpful ways.

- On the other hand, laws that are too general can end up being interpreted in ways that easily disregard their actual intent.

- This again reminds us of the importance of other measures to complement legal provisions, which will always be constrained to a certain level of generality. Their intent can be reinforced, for example, through implementing regulations, government guidance, or complaints mechanisms and access to remedy.

- Laws that are too prescriptive risk being inappropriate to the actual operating realities of many companies, and can distort practices in unhelpful ways.

- That brings me to my third point. That is, that

great care must be taken to understand and preserve the distinctions

between the actual scope of companies’ responsibility to respect human

rights and the reasonable scope of any civil liability provisions that legislation may introduce.

- The UNGPs make clear that companies have a responsibility not only

where they cause or contribute to a human rights harm, but also where

abuses are linked directly to their products and services – including at

remote tiers of their value chain – without any contribution on their

part.

- Legislative proposals that aim to include civil liability provisions

need a narrower scope. It would be unreasonable to attach liability to

scenarios where the company has not contributed to a harm.

- Yet laws should not imply that an absence of civil liability means an absence of responsibility.

- One way to address this distinction could be to require reporting by companies on the full scope of their responsibility, while constraining any civil liability provisions to situations where the company’s own actions or decisions have played a role.

- The UNGPs make clear that companies have a responsibility not only

where they cause or contribute to a human rights harm, but also where

abuses are linked directly to their products and services – including at

remote tiers of their value chain – without any contribution on their

part.

Enabling remedy is one of the most compelling arguments for considering civil liability in the context of legislation on human rights due diligence.

The fifth and final role of governments in this ‘smart mix’ is of course in providing access to remedy. This would warrant a separate discussion all of its own given the central importance for human rights of ensuring that people whose human rights are harmed can seek and secure remedy for those harms.

- Enabling remedy is one of the most compelling arguments for

considering civil liability in the context of legislation on human

rights due diligence.

- National development finance institutions or export credit agencies

may also offer some form of recourse to raise concerns about decisions

that have been made to support certain businesses or investments. The

independent complaints mechanism for the German, Dutch and French DFIs

has initiated a mediation process in response to a complaint from

communities in the DRC about a land conflict with a local subsidiary of a

Canadian company.

- Of course, the OECD National Contact Points may offer another mechanism for remedy at the international level, with governments intended to use their own leverage to bring companies and stakeholders to the table to resolve complaints. Unfortunately, most NCPs have failed to deliver on their promise so far. And they have almost never gone so far as to provide remedy to those harmed, with the refreshing and admirable exception in the case of Heineken working with the Dutch NCP and civil society last year.

So let me leave you with these key reflections by way of summary.

Efforts to embed respect for human rights into how business gets done are indispensable if we are to tackle the gross inequalities that plague societies today, and the threats to social cohesion and stability that are their ever more frequent result.

While the corporate responsibility to respect human rights is not voluntary or optional; it is far harder to implement where governments do not meet their own duties to protect human rights.

A critical role of government – which can thread among and between these five categories – is collaboration.

When the Guiding Principles speak about the need for governments to adopt a ‘smart mix’ of measures, the word ‘mix’ should be understood to be as important as the word ‘smart’.

There are five key types of measure that can make up such a mix: policy measures, guidance and support, integration in governments’ own transactions with business, legislation and regulation, and ensuring access to remedy. Yet each of these types of measure is inadequate on its own, and each is much stronger where most or all of the others are present.

Finally, I would be remiss not to note that a critical role of government – which can thread among and between these five categories – is collaboration.

Here in Germany there is a strong history of collaborative decision-making and consensus-building. This is seen also with regard to business and human rights – whether through your long history of social dialogue or through recent initiatives such as the Textile Industry Roundtable.

I look forward to joining you in some really collaborative thinking through the rest of the day as you explore the options to bring your different roles and responsibilities together, and start to define a smart mix of measures on the part of government, with the common purpose of building sustainable global supply chains based on rights-respecting business practices.