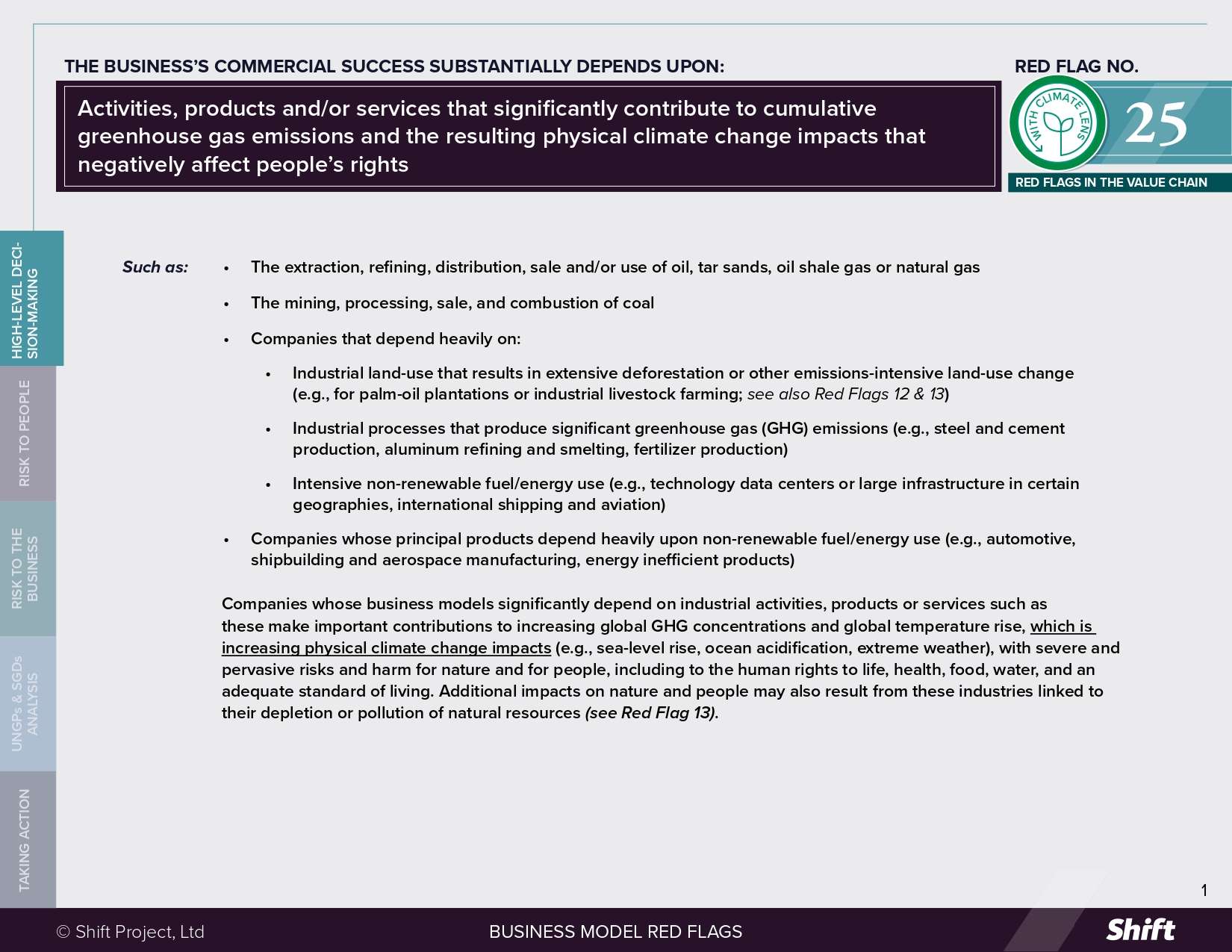

RED FLAG # 25

Activities, products and/or services that significantly contribute to cumulative greenhouse gas emissions and the resulting physical climate change impacts that negatively affect people’s rights

FOR EXAMPLE

- The extraction, refining, distribution, sale and/or use of oil, tar sands, oil shale gas or natural gas

- The mining, processing, sale, and combustion of coal

- Companies that depend heavily on:

- Industrial land-use that results in extensive deforestation or other emissions-intensive land-use change (e.g., for palm-oil plantations or industrial livestock farming; see also Red Flags 12 & 13)

- Industrial processes that produce significant greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (e.g., steel and cement production, aluminum refining and smelting, fertilizer production)

- Intensive non-renewable fuel/energy use (e.g., technology data centers or large infrastructure in certain geographies, international shipping and aviation)

- Companies whose principal products depend heavily upon non-renewable fuel/energy use (e.g., automotive, shipbuilding and aerospace manufacturing, energy inefficient products)

HIGHER-RISK SECTORS

- Oil and gas exploration, extraction and transportation

- Coal mining, processing and transportation

- Fossil fuel-based power generation (e.g., lignite, coal, oil and natural gas)

- Carbon-intensive industrial sectors (e.g., petrochemicals, steel, iron, cement, aluminum and construction inputs)

- Industrial-scale conventional agriculture (e.g., industrial livestock farming, palm oil plantations, and other commercial farming activities)

- Forestry and forest products

- Large-scale transportation (e.g., industrial land transport, marine shipping, aviation)

- Transportation manufacturing (e.g., automotive, shipbuilding, aerospace)

- Large-scale infrastructure, including real estate

- Information and Communication Technology (see also Red Flag 21)

- Financial institutions that are significantly financing higher-risk industries that lack robust transition planning

Companies whose business models significantly depend on industrial activities, products or services such as these make important contributions to increasing global GHG concentrations and global temperature rise, which is increasing physical climate change

impacts (e.g., sea-level rise, ocean acidification, extreme weather), with severe and pervasive risks and harm for nature and for people, including to the human rights to life, health, food, water, and an adequate standard of living. Additional impacts on nature and people may also result from these industries linked to their depletion or pollution of natural resources (see Red Flag 13).

Questions for Leaders

- How is your business model compatible with the objectives of the Paris Agreement?

- How do you consider the impact of your climate action or inaction on people and how have you identified and engaged with potentially impacted workers (including value chain workers), communities, or consumers?

- To what extent have you integrated human rights considerations into your approach to managing your climate change impacts?

- Have you considered the regulatory, reputational, legal and financial risks associated with maintaining business as usual or taking insufficient action to address your climate impacts, including those risks that flow from the human consequences of your climate impacts?

- To what extent have you explored potential business opportunities in developing products or services that help achieve net zero in ways that respect and advance human rights?

How to use this resource. ( Click on the “+” sign to expand each section. You can use the side menu to return to the full list of red flags, download this Red Flag as a PDF or share this resource. )

Understanding Risks and Opportunities

Risks to People

|

Risk to the Business

-

Reputational risks: Individual company climate change impacts that affect human rights can generate considerable attention and multinational corporations are often targeted for criticism, particularly where people believe that appealing to governments may have little effect.

-

Even where legal action against a company relating to the human rights impacts of climate action or lack of action is unsuccessful, this can still present considerable reputational risk to the company.

-

Non-judicial proceedings can create reputational risks. Examples include communications by UN experts on the responsibilities of the financial backers of Saudi Aramco under the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, and a complaint with the American National Contact Point against insurance broker Marsh challenging the East African Crude Oil Pipeline planned by TotalEnergies in Uganda.

-

In 2022, the UN Commission on Human Rights (CHR) of the Philippines published its final report finding that the world’s biggest polluting companies can be held responsible for human rights violations and threats arising from climate impacts. CHR announced that the 47 investor-owned corporations, including Shell, ExxonMobil, Chevron, BP, Repsol, Sasol, and Total, could be found legally and morally liable for human rights harms to Filipinos resulting from climate change.

-

In 2025, the UK charity ActionAid publicly cut ties with HSBC, citing the bank’s continued financing of fossil fuel and industrial agriculture projects—amounting to over £153 billion between 2021 and 2023—as evidence the company is consistently “choosing profit over people and planet”. Civil society groups like BankTrack, Indigenous rights advocates, and major investor coalitions such as ShareAction have raised similar concerns about HSBC’s increasing financial, legal, and reputational risks tied to climate change.

-

-

Legal, financial and regulatory risks: Companies that do not take action to address their climate change impacts can face legal action for their contribution or preemptive legal action to avoid company activities that are perceived to negatively impact local communities or other stakeholders. Since 2016, there has been significant growth in climate change-related legislation. As of July 2025, 2967 climate change cases have been filed globally. Around 20% of climate cases filed in 2024 targeted companies, or their directors and officers. According to the London School of Economics’ Grantham Institute, which analyzes climate change litigation annually, “The range of targets of corporate strategic litigation continues to expand, including new cases against professional services firms for facilitated emissions, and the agricultural sector for climate disinformation”. While highly anticipated legal decisions have faced evidentiary hurdles, they have: (a) acknowledged the connection between GHG emissions, physical climate change and impacts on people, (b) scrutinized whether companies are taking reasonable and sufficient action to mitigate their impacts, and (c) explored the principle of companies being held liable for climate-related harm. Some notable legal developments include:

-

Litigants have had high profile successes in international courts and tribunals, including at the International Court of Justice and European Court of Human Rights, as well as advisory opinions form the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. The decisions and opinions emerging from these international bodies, which broadly affirm the right to a healthy environment, including a stable climate, provide important points of reference for litigation more broadly.

-

Royal Dutch Shell was taken to court in 2019 in the Netherlands on human rights grounds relating to the climate impact of its business. Although Shell won an appeal of the case brought by Milieudefensie in 2024, the court emphasised that companies, especially those that have contributed to climate change, have a responsibility and power to contribute to combating climate change. Further, the court affirmed in unequivocal terms that “protection from dangerous climate change is a human right” and these rights extend to what can be required of Shell.

-

A Peruvian farmer filed a lawsuit against German Energy giant RWE in German courts. His case argued that because RWE’s GHG emissions—estimated at 0.5% of historical global emissions—contributed significantly to glacial melting and heightened flood risk that impacted his property in Huaraz, Peru, RWE should compensate him for 0.5% of the costs of his flood protection investments. While the case was ultimately dismissed, after multiple appeals and years of litigation, for the first time, a court affirmed that large emitters could be held civilly liable under German law for climate damage—even across borders—based on scientific attribution and proportionate responsibility.

-

In September 2015, typhoon survivors and civil society groups in the Philippines, supported by Greenpeace and NGOs, filed a first‑of‑its‑kind petition with the Philippine Commission on Human Rights (PCHR), calling for a formal inquiry into whether 47 major corporate emitters (including Shell, ExxonMobil, Chevron, BP, Repsol, Sasol and Total) violated Filipinos’ rights by fueling climate change. The PCHR officially accepted the complaint in December 2015, held hearings from 2016 to 2018, and gathered extensive scientific data, testimonials, and expert briefs. In May 2022, the PCHR released its National Inquiry on Climate Change report, which concluded that the companies engaged in “wilful obfuscation” of climate science and that their actions were both morally and legally liable for human rights harms to Filipinos resulting from climate change.

-

In May 2024, Vermont became the first U.S. state to pass a “climate superfund” law aimed at holding major fossil fuel companies financially accountable for the costs of climate change. The law targets companies responsible for over one billion metric tons of GHG emissions and seeks to recover the state’s climate-related costs—including infrastructure damage, public health impacts, and other social harms—dating back to 1995. The move has inspired similar legislative efforts in states like New York, Maryland, and California. As of mid-2025, Vermont is still in the implementation phase, developing a damages assessment, while facing a legal challenge from the fossil fuel industry aiming to block the law before enforcement begins.

-

- Regulatory risks: Regulators globally are increasingly holding high-emitting companies accountable for both climate and human rights impacts. Governments are implementing carbon pricing mechanisms and stricter emissions standards, which increase operational costs for high emitting industries. Further, the EU’s Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive requires large firms to identify and mitigate adverse environmental and human rights impacts across their value chains and expects companies to transition their operations and value chains to a net zero economy in a rights-respecting way. (Note: As of publication, the existing text has been suspended pending a renewed legislative process that is expected to introduce some revisions.)

- Financial risks: Financial institutions are increasingly concerned about the longer-term, climate-linked financial stability of their portfolios, with investors increasingly favoring companies with robust climate strategies, potentially leading to reduced capital access for firms that fail to evolve their business models or do so at too slow a pace. Climate-related shareholder activism has increased dramatically in recent years.

- Business continuity risks: Companies that fail to address their contribution to climate change contribute to systemic risks with material, economy-wide implications for business continuity. For example:

- operational disruptions from extreme heat and declining worker productivity—estimated to fall 2–3% for every degree Celsius above 20°C, affecting billions of workers worldwide (e.g., in agricultural, construction, and manufacturing sectors).

-

critical process disruptions due to lack of raw materials (e.g., water-intensive manufacturing processes being halted by droughts)

-

supply chain disruptions from climate-related events, which could lead to up to $2.5 trillion in net losses by mid-century

What the UN Guiding Principles Say

|

In June 2023, the UN Working Group on the issue of human rights and transnational corporations and other business enterprises issued an information note on the UNGPs and climate change. In reference to the human rights instruments identified in UN Guiding Principle 12, the Commentary on Principle 12, the widely recognized right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment, and the understanding that anthropogenic GHG emissions are known to cause foreseeable and severe human rights impacts, the working group states that “States and business enterprises have obligations and responsibilities with respect to climate change, and with respect to the impacts of climate change on human rights.” According to the Working Group, “The obligations of States under the Guiding Principles to protect against human rights impacts arising from business activities includes the duty to protect against foreseeable impacts related to climate change.” With respect to business enterprises, the Working Group confirms that the responsibilities of those enterprises “under the Guiding Principles to respect human rights and not to cause, contribute to or be directly linked to human rights impacts arising from business activities, include the responsibility to act in regard to actual and potential impacts related to climate change.” As physical climate impacts are primarily the result of cumulative, global GHG emissions, it may be difficult to establish that any one company has caused a particular, location-specific climate-related harm (e.g., that one company’s GHG emissions in Australia are directly responsible for an extreme weather event in India). However, where a company makes a substantial contribution to cumulative GHG emissions, because their business model substantially relies upon them doing so, that company can be said to have contributed to climate harm, thus requiring the company to “take the necessary steps to cease or prevent its contribution and use its leverage to mitigate any remaining impact to the greatest extent possible”. This supports the expectation that companies with this business model feature should develop and implement robust, credible and Paris-aligned climate transition plans that respect the rights of workers and communities, as well as use their leverage toward achieving broader systemic transition. Corporations can also be linked to the human rights impacts associated with climate change through their business relationships. Examples of such linkage include a retailer sourcing from a supplier whose operations are carbon intensive, without any indication that the supplier will reduce them; or an investment fund holding equity in a fossil fuel company that has no discernible strategy to reduce its contributions to climate change. |

Possible contributions to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

Addressing impacts on people associated with this red flag can contribute to a range of SDGs depending on the impact concerned, but the most obvious and notable is:

-

SDG 13: Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts

Taking Action

Due Diligence Lines of Inquiry

-

Are we developing or have we published a robust, credible and science-based climate action strategy or transition plan that recognizes and addresses impacts on workers and communities arising from climate action?

-

How are we engaging our own workforce, our value chain workers, affected local communities and consumers/end-users in discussions about potential or actual action to address climate change impacts?

-

How are we evolving our governance, strategy, risk management and metrics/targets to ensure alignment with the objectives of the Paris agreement? How have we integrated potential impacts on people evolving from that evolution?

-

Recognizing both the consequences for the climate and for people’s human rights of GHG emissions:

-

Do we: undertake a robust analysis and disclosure of our contribution to global GHG emissions, including the following?

-

Identifying all our Scope 1, 2 and 3 GHG emissions throughout all our operations, with such identification being science-based, verifiable and informed by input from experts

-

Identifying hotspots across our operations and value chains

-

Disclosing climate-related information through recognized frameworks, such as GRI, CDP, TCFD, ESRS E1, or IFRS S2

-

-

Do we set ambitious, transparent and verifiable climate-related targets, including:

-

GHG emissions reduction targets across Scopes 1, 2 and 3 emissions

-

Transition-specific alignment targets that directly reflect our company’s progress on critical decarbonization milestones within our sector

-

-

-

Do we disclose the details of how our capital expenditure plan aligns with our climate action and human rights objectives?

-

Have we undertaken scenario analysis to assess resilience of the company’s operations and value chains, as well as the people its operations and value chains may impact, under various warming pathways (e.g., 1.5°C or 4°C)?

-

How do we ensure that our public affairs and policy advocacy activities are aligned with the objectives of our climate and human rights actions?

-

Do we rely on land-based carbon dioxide removals or the use of carbon credits to meet our GHG emissions reduction targets? If so, do we have mechanisms in place to evaluate the social and environmental integrity of doing so?

-

How do we assess whether our climate-related strategies and plans could impact stakeholder groups, namely, our own workers, workers in the value chain, communities and end users, with a particular focus on vulnerable populations?

Mitigation Examples

For companies whose business models substantially rely upon high emitting activities, products or services, examples of integrated, ambitious, organization-wide, and Paris-aligned action is not yet common. However, there are examples of companies that are making important, if partial, strides to address their contribution to climate impacts. For example:

Partial business model transition:

-

TransAlta is one of Canada’s largest electricity producers and is in the progress of changing its business model, undergoing a partial low carbon transition away from being a predominantly coal-fired power producer towards natural gas, renewables and energy storage. The company also played an active role in the provincial government’s measures to support workers and communities impacted by the transition.

-

Volvo Cars is attempting to transition its business model from producing vehicles dependent on fossil fuels to an electrified vehicle fleet. It originally targeted a fully electric vehicle offering by 2030, but the company updated its target in 2024 to 90–100% electrified sales by 2030. To address human rights-related risks in its value chain resulting from the transition to electric vehicles, particularly around critical minerals for components such as batteries, Volvo is exploring the use of different traceability techniques and “battery passports” that record the origins of raw materials, components, recycled content and carbon footprint of the battery.

Reconceptualizing climate-related target setting:

-

Large agrifood companies, such as Danone, Mars, Nestlé and PepsiCo, have acknowledged that, given the realities of the climate challenge within their sector, GHG emissions reduction targets are necessary but not sufficient. These companies have also set no-deforestation commitments for some or all high-risk commodities where deforestation is most prevalent. According to the 2025 Corporate Climate Responsibility Monitor, “these examples demonstrate how transition-specific alignment targets can complement emission reduction targets to guide sector-specific corporate transitions”.

Decision-useful climate disclosures that address the Just Transition:

-

Scottish and Southern Energy (SSE) in the UK has publicly disclosed its Just Transition strategy, which considers the impact its transition plan has on people.

-

In 2022, Enel was the first company to fully align its corporate climate disclosures with the Climate Action 100+ Net Zero Company Benchmark, which include Just Transition elements.

Collaborative initiatives that use leverage to affect change:

-

Climate Action 100+ is an investor-led initiative composed of around 700 investors globally and responsible for over USD 68 trillion in assets under management, which aims to ensure the world’s largest corporate greenhouse gas emitters take action on climate change.

Alternative Models

-

Orsted, the Danish energy company, was once one of the highest emitting energy companies in Europe, due to its coal-fired power and its oil and gas assets. Since 2009 it has undergone a transition to become a global leader in renewable energy, reducing its GHG emissions by 98% (from 2006 levels, scope 1 & 2 only) and aims to be net zero GHG emissions across its value chain (scope 3) by 2040. The company also continues to use its leverage in support of broader systemic transition, in the context of collaborative initiatives, as well as in advocating for the global elimination of fossil fuel subsidies. While there are concerns about the company’s transition strategy, including its 2017 oil and gas divestment (rather than gradual and actively managed decommissioning), this is one of very few examples of a high emitter’s strategic reorientation, with important lessons for other transitioning or soon-to-be transitioning companies.

-

Rivian’s business model distinguishes itself from traditional automakers by focusing exclusively on purpose-built electric vehicles, avoiding reliance on internal combustion engines that drive global greenhouse gas emissions. Its proprietary platform enables efficient production of multiple vehicle models, with efforts to address emissions and social-related risks elsewhere in its value chain. For example, the company is investing in a “supplier park” in close proximity to its Illinois manufacturing facility in order reduce transportation emissions and improve supplier oversight. The company is developing a series of strategic partnerships, including its Amazon electric delivery fleet, to expand market reach.

-

Oatly’s business model is built on replacing dairy with oat-based alternatives, which studies show have 62–78% lower greenhouse gas emissions per liter than cow’s milk. This positions the company as a lower-carbon option in the food sector, even if independent reviews caution that some of the carbon benefits are offset by the impacts from product processing, packaging, and sourcing.

-

In Australia, where the market for “carbon neutral cattle” is growing, farmers are experimenting with carbon neutral cattle systems focused on soil carbon sequestration to offset greenhouse gas emissions, aiming for net-zero emissions from cattle birth to sale.

-

In response to foreign competitive pressures Sweden has developed expertise in niche environmentally friendly steel products and is developing fossil fuel free steel. Such technological innovation is seen as essential to maintaining Swedish competitiveness in the sector.

Other tools and resources

-

Shift (2023) Climate Change & human rights: Avoiding pitfalls for financial institutions

-

Frequently asked questions on Human Rights and Climate Change, Fact Sheet No. 38, United Nations Hunan Rights Office of the High Commissioner, 2021

-

UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights’ Climate Change Hub

-

Amnesty International’s Climate Change Hub

-

BSR (2025) Transforming Business Models: A BSR framework to capture the opportunity of business transformation within planetary boundaries

-

Germanwatch (2018) Guidance on climate risks and human rights in the insurance sector

-

AIM Progress (2025) Bringing people and their rights into corporate climate action

-

Human Level (2024) Navigating the Just Transition: Practical Steps for Business Leaders

-

UN Working Group on the issue of human rights and transnational corporations and other business enterprises (2023) Information Note on Climate Change and the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights provides clear guidance (in section IV) on integrating climate considerations into HRDD.

Citation of research papers and other resources does not constitute an endorsement by Shift of their conclusions.

Business Model Red Flags

Business Model Red Flags  Tool for Indicator Design

Tool for Indicator Design