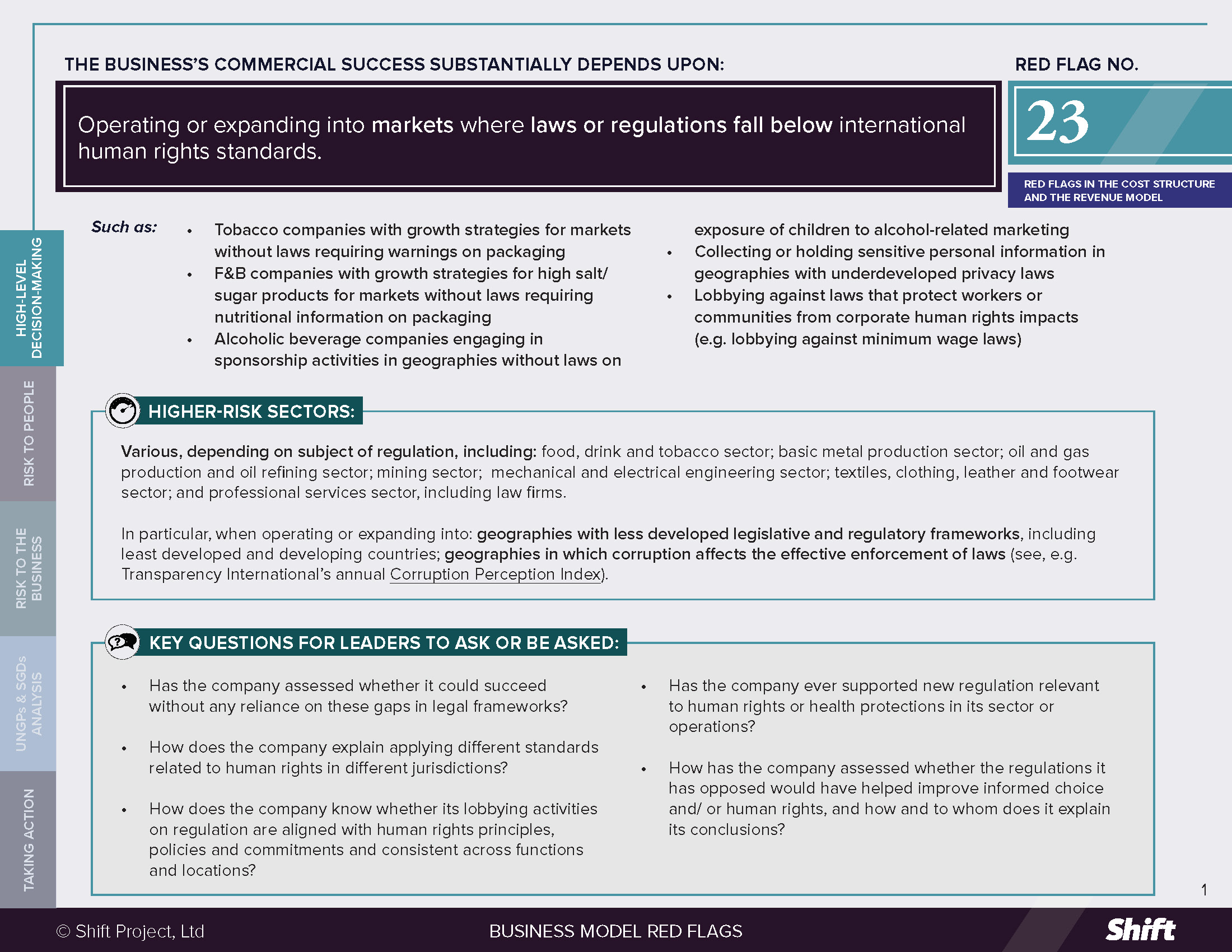

RED FLAG # 23

Operating or expanding into markets where laws or regulations fall below international human rights standards.

For Example

- Tobacco companies with growth strategies for markets without laws requiring warnings on packaging

- F&B companies with growth strategies for high salt/ sugar products for markets without laws requiring nutritional information on packaging

- Alcoholic beverage companies engaging in sponsorship activities in geographies without laws on exposure of children to alcohol-related marketing

- Collecting or holding sensitive personal information in geographies with underdeveloped privacy laws

- Lobbying against laws that protect workers or communities from corporate human rights impacts (e.g. lobbying against minimum wage laws)

Higher-Risk Sectors

Various, depending on subject of regulation, including: food, drink and tobacco sector; basic metal production sector; oil and gas production and oil refining sector; mining sector; mechanical and electrical engineering sector; textiles, clothing, leather and footwear sector; and professional services sector, including law firms.

In particular, when operating or expanding into: geographies with less developed legislative and regulatory frameworks, including least developed and developing countries; geographies in which corruption affects the effective enforcement of laws (see, e.g. Transparency International’s annual Corruption Perception Index).

Questions for Leaders

- Has the company assessed whether it could succeed without any reliance on these gaps in legal frameworks?

- How does the company explain applying different standards related to human rights in different jurisdictions?

- How does the company know whether its lobbying activities on regulation are aligned with human rights principles, policies and commitments and consistent across functions and locations?

- Has the company ever supported new regulation relevant to human rights or health protections in its sector or operations?

- How has the company assessed whether the regulations it has opposed would have helped improve informed choice and/ or human rights, and how and to whom does it explain its conclusions?

How to use this resource. ( Click on the “+” sign to expand each section. You can use the side menu to return to the full list of red flags, download this Red Flag as a PDF or share this resource. )

Understanding Risks and Opportunities

Risks to People

Where the business model is substantially dependent on gaps in legal frameworks, the company may engage in:

- Practices associated with maintaining this business model feature risk perpetuating a “race to the bottom,” as countries compete with lower regulatory standards to attract corporate investment.

- Lobbying against measures or laws that protect people from human rights impacts, for example lobbying against:

- (increased) minimum wage laws, affecting, inter alia, the right to just and favorable conditions of work, including decent remuneration;

- Indigenous title to land affecting, inter alia, Indigenous people’s rights;

- restrictions on emissions into land, sea and air, affecting the right to an adequate standard of living;

- laws that support informed choice, affecting the right to health.

- Legal strategies that prevent the state from protecting people from human rights impacts (potentially various), for example:

- seeking to use investment treaties (including stabilization clauses) to limit states’ abilities to enact or amend legislation or regulations that increase human rights protection;

- seeking to enforce intellectual property rights against public health imperatives.

Risks to the business

- Reputational and Operational: risks arise due to inconsistencies between what the company says in public and in private regarding regulatory protections, and in what it does in different parts of the world based on different levels of regulatory protection. Reputations may also be open to attack where the company invests considerable resources in weakening human rights protections.

- Legal and Financial Risk: where a company mounts an unsuccessful legal challenge to government regulation aimed at public protection, it may face financial penalties. For example, tobacco company Philip Morris was ordered to pay the Australian government millions of dollars after unsuccessfully suing the nation over its plain-packaging laws.

- Financial Risks: can arise where investors consider companies’ attempts to influence public policy in their investment decisions. For example, US-based Trillium Asset Management reportedly monitors the levels and recipients of corporate giving, corporate policies on political contributions and membership of industry (lobbying) associations as part of their background research for stock selection in their socially responsible investment funds.

- Business Continuity Risks: where business contributes to the degradation of resources or people on which the business relies, e.g. by lobbying against laws that protect consumers or the community or limit environmental degradation.

What the UN Guiding principles say

*For an explanation of how companies can be involved in human rights impacts, and their related responsibilities, see here.

- Under the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, the corporate responsibility to respect human rights “exists independently of States’ abilities and/or willingness to fulfil their own human rights obligations, and … exists over and above compliance with national laws and regulations protecting human rights.” (Principle 11, Commentary) In other words, “all business enterprises have the same responsibility to respect human rights wherever they operate” (Principle 23, Commentary), whether or not they have a domestic legal obligation to do so. As such, adopting an inherently uneven, compliance-based approach risks breaching the company’s responsibility in places where laws do not meet internationally accepted human rights standards.

- The UNGPs note that companies should, “strive for coherence between their responsibility to respect human rights and policies and procedures that govern their wider business activities and relationships [including] …. lobbying activities where human rights are at stake.” (Principle 16, Commentary).

- Where the company actively lobbies against or takes action to constrain laws that have the practical effect of furthering respect for human rights, it risks contributing to human rights impacts, whether as a sole contributor or as a result of the aggregate contribution of several actors.

- Where a company is benefiting from an absence of protection of rights in the countries where it operates, it may be directly linked to impacts; where it is aware of this and does nothing, it may, depending on a number of factors, be considered to be contributing to the impacts.

Possible Contributions to the SDGs

Addressing impacts on people associated with this red flag indicator can contribute to a range of SDGs depending on the impact concerned, for example:

SDG 3: Good Health and Well Being, in particular Target 3.5: strengthen the prevention and treatment of substance abuse, including narcotic drug abuse and harmful use of alcohol; and Target 3.10: strengthen the implementation of the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control in all countries, as appropriate.

SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth, in particular Target 8.5: by 2030, achieve full and productive employment and decent work for all women and men, including for young people and persons with disabilities, and equal pay for work of equal value.

SDG 16: Peace, justice and strong institutions, in particular Target 16.7: ensure responsive, inclusive, participatory and representative decision-making at all levels; and Target 16.10: ensure public access to information and protect fundamental freedoms, in accordance with national legislation and international agreements.

Taking Action

Due Diligence Lines of Inquiry

- What legal frameworks are we actively seeking, supporting or opposing in order to execute our strategy? E.g. what regulatory drivers determine our entry into or exit from a sourcing location or sales market? How do these legal frameworks (or relevant elements) map against gaps in human rights protections?

- Do we have a policy on when and how we will lobby against regulatory initiatives that include provisions aimed at increasing consumer access to information about their health choices or at protecting other human rights?

- Have we assessed whether and to what extent our engagements with governments on regulatory developments are in line with our responsibility to respect human rights and enable governments to introduce human rights protections? Have we examined our lobbying activities in light of our own human rights commitments and strategies?

- Do our government affairs team engage routinely with our corporate responsibility/ sustainability/ human rights teams, with a view to internal alignment?

- Where we use external lobbying organizations, are our corporate responsibility/ sustainability/ human rights team consulted on the terms of their mandate?

- Do we disclose our position on key public policy issues? Do we reveal our external memberships, donations and methods of influence? If not, why not?

Mitigation Examples

*Mitigation examples are current or historical examples for reference, but do not offer insight into their relative maturity or effectiveness.

Applying purpose and principles to lobbying activities:

- In 2017 Campbell’s Soup withdrew from the Grocery Manufacturers Association citing “our purpose and principles,” including positions on food labelling. When the United States Food and Drug Administration agreed to extend a deadline for food and beverage companies’ to introduce a “Nutrition Facts Panel,” the company announced it was “continuing to strive to meet the original deadline.”

- The CEO Water Mandate’s Guide to Responsible Business Engagement with Water Policy (2010) contains “Principles for Responsible Water Policy Engagement.” Principles 1 and 2 provide that “responsible corporate engagement in water policy must be motivated by a genuine interest in furthering efficient, equitable, and ecologically sustainable water management” and that companies should ensure “that activities do not infringe upon, but rather support, the government’s mandate and responsibilities to develop and implement water policy…”.

Contributing to a regulatory environment that enables respect for rights:

- Oil and gas companies have jointly pressed a government to improve transparency requirements before proceeding with bids for concessions, in order to level the playing field and avoid human rights performance becoming a competitive issue. (See Shift’s Using Leverage guide at p. 22).

- In 2014, eight apparel brands wrote to the Cambodian deputy prime minister and the chairman of the local Garment Manufacturers Association to say they were “ready to factor higher wages” into their pricing.

Alternative Models

Companies striving to ensure a living wage across their operations and supply chain seek to mitigate the effects of operations in countries in which there is no, or an inadequate, minimum wage. ACT (Action, Collaboration, Transformation) is an “agreement between global brands and retailers and trade unions to transform garment, textile and footwear industry and achieve living wages for workers through collective bargaining at industry level linked to purchasing practices.” Through industry-level collective bargaining in sourcing countries, companies seek to avoid competing with each other based on lower wages (and regulations that enable this), but rather on other factors.

Other tools and Resources

- Business for Social Responsibility (2019) Human Rights Policy Engagement: The Role of Companies: a BSR report on a human rights-supportive approach to public policy engagement.

Business Model Red Flags

Business Model Red Flags  Tool for Indicator Design

Tool for Indicator Design