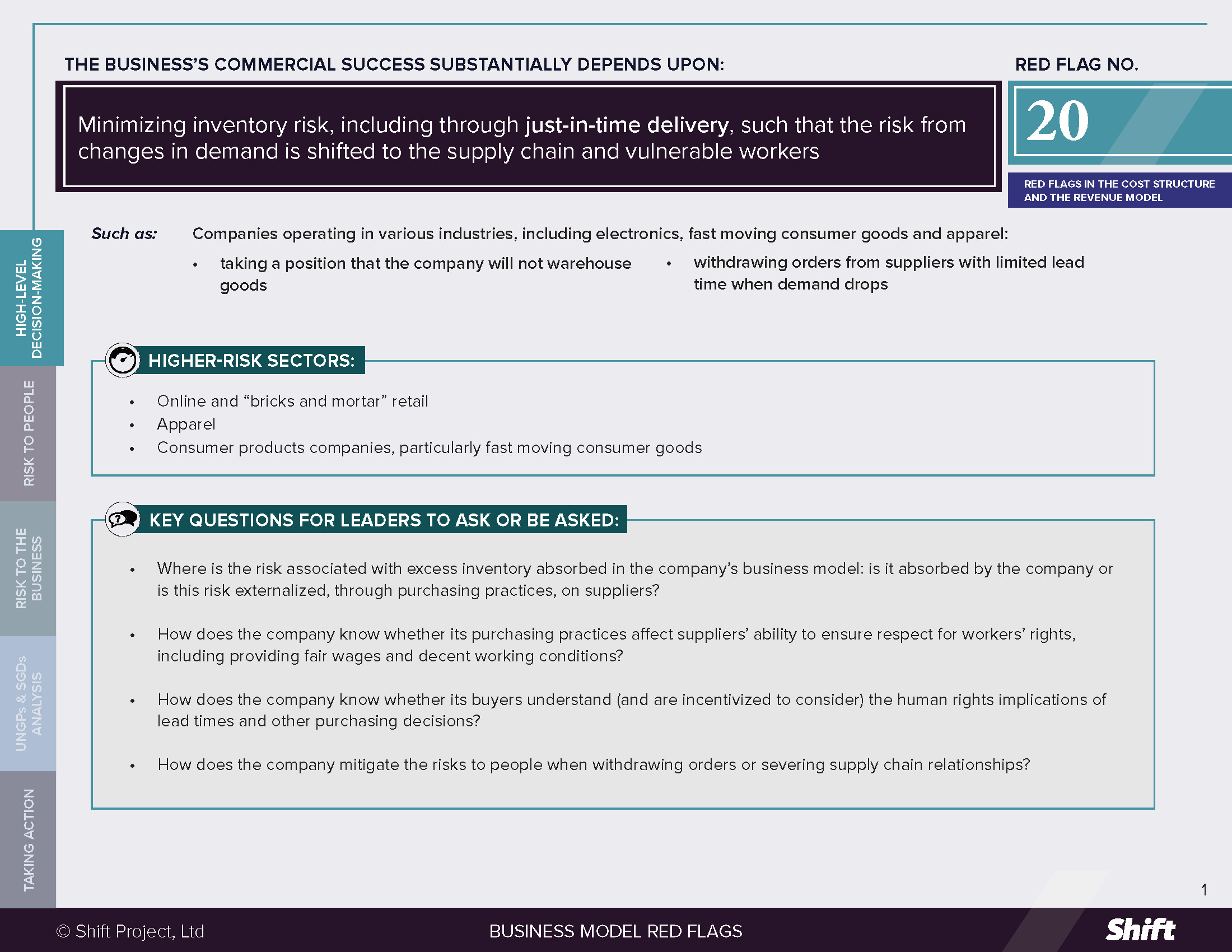

RED FLAG # 20

Minimizing inventory risk, including through just-in-time delivery, such that the risk from changes in demand is shifted to the supply chain and vulnerable workers.

For Example

Companies operating in various industries, including electronics, fast moving consumer goods and apparel:

- taking a position that the company will not warehouse goods

- withdrawing orders from suppliers with limited lead time when demand drops

Higher-Risk Sectors

- Online and “bricks and mortar” retail

- Apparel

- Consumer products companies, particularly fast moving consumer goods

Questions for Leaders

- Where is the risk associated with excess inventory absorbed in the company’s business model: is it absorbed by the company or is this risk externalized, through purchasing practices, on suppliers?

- How does the company know whether its purchasing practices affect suppliers’ ability to ensure respect for workers’ rights, including providing fair wages and decent working conditions?

- How does the company know whether its buyers understand (and are incentivized to consider) the human rights implications of lead times and other purchasing decisions?

- How does the company mitigate the risks to people when withdrawing orders or severing supply chain relationships?

How to use this resource. ( Click on the “+” sign to expand each section. You can use the side menu to return to the full list of red flags, download this Red Flag as a PDF or share this resource. )

Understanding Risks and Opportunities

Risks to People

- Some business models support commercial viability by externalizing the risks associated with changing levels of consumer demand on suppliers, rather than absorbing it in the business model.

- Companies may do this by way of:

- Making last minute demands, changes or cancellation of orders;

- Using contracts by which the supplier assumes the cost and risk of the product until delivered;

- Avoiding warehousing goods by utilizing a “just in time” inventory/sourcing model.

- As a result:

- When demand spikes, and the purchasing company places large volume orders with short lead times, suppliers may see no alternative but to demand excessive overtime. (Right to just and favorable conditions of work; Right to a family life; Right to Health).

- A joint ETI/ILO survey on purchasing practices in 2017, to which responses were received from over 1,400 suppliers in 87 countries, found that only 17% of suppliers surveyed considered their orders to have enough lead time.

- When demand drops, the purchasing company may cancel orders on short notice and/or refuse to take responsibility for goods that have already been produced. IndustriALL has noted that such cancellations leave factories holding the goods, unable to sell them to the customer that ordered them, and in many cases unable to pay the wages of the workers who made them.

- When demand spikes, and the purchasing company places large volume orders with short lead times, suppliers may see no alternative but to demand excessive overtime. (Right to just and favorable conditions of work; Right to a family life; Right to Health).

- Purchasing practices such as this may, without appropriate mitigation measures, place heavy pressure on suppliers working on narrow margins. Risk and its associated costs are pushed up the supply chain and absorbed by the most vulnerable people – such as factory workers, including migrant workers, women workers, producers and small-holder farmers – affecting their livelihoods and those of their families. Suppliers under excessive pressure may not pay wages or overtime, or not provide safe working conditions; they may pregnancy test workers pursuant to a view that pregnant workers are not financially viable. Risks are exacerbated when the purchasing company(ies) provide little or no commitment to long-term sourcing, disincentivizing investment in improving working conditions (Right to just and favorable conditions of work; Right to Health).

Risks to the Business

- Operational Risks:

- Purchasing practices that situate inventory risk with suppliers can leave suppliers with cash flow challenges and unpredictability that disincentivizes them from investing in compliance with codes of conduct. Such practices can also cause suppliers to outsource (including illegally) to subcontractors, increasing the complexity of the supply chain and reducing visibility and control on the part of the buying company.

- Where the company does not keep an inventory of its products and relies on a small number of suppliers, it can be vulnerable to inventory shortages: in 2019, German-based Adidas’s sales growth declined due to “supply chain shortages” when “the company’s suppliers—nearly all of whom are based outside Germany—did not keep up with customer demand.”

- The Covid-19 situation in 2020 further demonstrated the risks to the company of relying on, inter alia, just in time models and the detrimental impact of this practice on supply chain resilience.

- Reputational and Financial Risks:

- Companies with purchasing practices that lag behind leading practices may receive poor results in the Better Buying review, a growing online platform that allows suppliers to anonymously rank the buying practices of brands and retailers.

- During the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic, companies leaving overseas suppliers with excess inventory received negative publicity, including through Workers’ Rights Consortium’s “Brand Tracker” which listed apparel labels and retailers that were and were not paying their suppliers for orders in production or completed. From an investment perspective, research on the link between public sentiment on corporate responses to the pandemic and financial flows found that companies with labor and supply chain practices that were seen as taking action to secure their supply chain experienced higher institutional money flows and less negative returns.

What the UN guiding principles say

*For an explanation of how companies can be involved in human rights impacts, and their related responsibilities, see here.

The UNGPs note that companies should “strive for coherence between their responsibility to respect human rights and policies and procedures that govern their wider business activities and relationships [including] …. procurement practices.” (Principle 16, Commentary).

If a company engages in purchasing practices that place undue time and/or financial pressure on suppliers, incentivizing or facilitating them to cause human rights impacts on workers, they contribute to impacts.

Possible Contributions to the SDGs

Addressing risks to people associated with this red flag indicator can contribute to, inter alia:

SDG 10: Reducing inequalities within and between countries.

This goal becomes relevant as profit margins and returns are concentrated at the buyer/investor level, with less and less value making it into the pockets of the poorest in the supply chain.

SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth, in particular Target 8.8 on protecting “labor rights and promot[ing] safe and secure working environments for all workers, including migrant workers, in particular women migrants, and those in precarious employment.

SDG 1: End Poverty in All its Forms Everywhere, in particular Targets 1.1 and 1.2 on eradicating extreme poverty and reducing by half the number of people living in poverty (according to national definitions).

Taking Action

Due Diligence Lines of Inquiry

- Do we have sufficient budget allocated to warehousing products? If not, how are we ensuring that factories can produce in advance and keep overtime within acceptable limits?

- Do buyers have sufficient knowledge, incentives and support to assess how and when their decisions will place human rights at risk, and to know from whom to seek assistance when they do?

- How do we know whether our buyers follow our processes, rules or guidelines in practice when engaging or contracting with suppliers?

- Do we engage with our suppliers in ways that help us understand how far they can go to meet our demands while still respecting the rights of their workers? Do we work with suppliers in countries of production to increase worker protections?

- Do we take a short term, transactional approach to supply chains or do we develop supply chain partnerships? For example, do we see high turnover among suppliers?

Mitigation Examples

*Mitigation examples are current or historical examples for reference, but do not offer insight into their relative maturity or effectiveness.

- “Kellogg undertakes a ‘joint business planning process’ with its key suppliers that includes the evaluation of its responsible sourcing practices. Issues such as purchasing practices, ordering, lead-time expectations, production schedule changes, and complicated specifications for ingredients and sizes are discussed with suppliers and that responsible sourcing is also embedded in global sourcing events and category development. In addition, Kellogg discloses that procurement leadership and category managers are responsible for the execution of the Global Sustainability Commitments, including social accountability, which is reflected in their annual performance plans and annual incentives.” (Know the Chain).

- ACT (Action, Collaboration, Transformation) is an “agreement between global brands and retailers and trade unions to transform garment, textile and footwear industry and achieve living wages for workers through collective bargaining at industry level linked to purchasing practices.” In September 2019, ACT adopted a joint due diligence framework including Global Purchasing Practices Commitments, a Responsible Exit Policy and Check List and a Purchasing Practices Self-Assessment tool (covering64 different aspects of purchasing practices in 16 areas), including a commitment to “fair terms of payment” and “better planning and forecasting.” The ACT Accountability and Monitoring framework provides ACT member brands with an agreed set of indicators and monitoring instruments to implement their purchasing practices commitments.

- At a time of decreased sales during the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic, UK supermarket Morrisons committed to advancing payments to its smaller foodmakers, farmers and businesses that stock its shelves; H&M announced that it would take delivery of already produced garments, as well as goods in production, and that the goods would be paid for under previously agreed payment terms and prices; L’Oréal prioritized immediate payments to and shortening payment terms with suppliers who were at risk of going out of business; and Unilever offered early payment to its most vulnerable small and medium-sized suppliers to help them with financial liquidity. (See Triponel and Sherman (2020)). Primark created the Primark Wage Fund, Asia to help pay the wages of garment workers affected by Primark’s decision to cancel clothing orders.

Alternative Models

Spanish fashion company Alohas’ “business model revolve[s] around an on-demand production process.” The company previews upcoming designs to customers early in the season and makes them available at a discount rate. Once it calculates how many units of each new style should be produced it commences manufacturing. Alohas notes that “on-demand reverts the sales cycle by applying a discount for early purchases and offering the product at full price only once stock has been made available. Meaning we don’t adhere to the traditional sales calendar anymore.”

Other Tools and Resources

- ACT (Action, Collaboration, Transformation), including the ACT Global Purchasing Practices Commitments.

- ILO (2017) Purchasing practices and working conditions in global supply chains: Global Survey results: provides the results of an ILO/ETI global survey on purchasing practices and working conditions, to which over 1,400 suppliers from 87 countries responded, with the sample covering nearly 1.5 million workers.

- ETI (2017) Guide to Buying Responsibly: The guide includes best practice examples and outlines the five key business practices that influence wages and working conditions.

- Better Buying has created a tool for suppliers to anonymously rate their buyers against 7 purchasing practices, developed through consultation with suppliers. Buttle (2018) Can there be fair rules for the ‘purchasing practices’ game?: a ETI blog post from ETI’s Apparel and Textiles Lead summarizes standards for company purchasing practices and offers recommendations for improvements in practice.

- Workers’ Rights Consortium’s “Brand Tracker” lists apparel labels and retailers that were and were not paying their suppliers for orders in production or completed during the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic.

- A. Triponel and C Bader (2020) Coronavirus is shining the spotlight on unhealthy supply chains: cleaning them up will help both business resilience and worker wellbeing.

- A. Triponel and J. F. Sherman (2020) Moral bankruptcy during times of crisis: H&M just thought twice before triggering force majeure clauses with suppliers, and here’s why you should too.

Business Model Red Flags

Business Model Red Flags  Tool for Indicator Design

Tool for Indicator Design