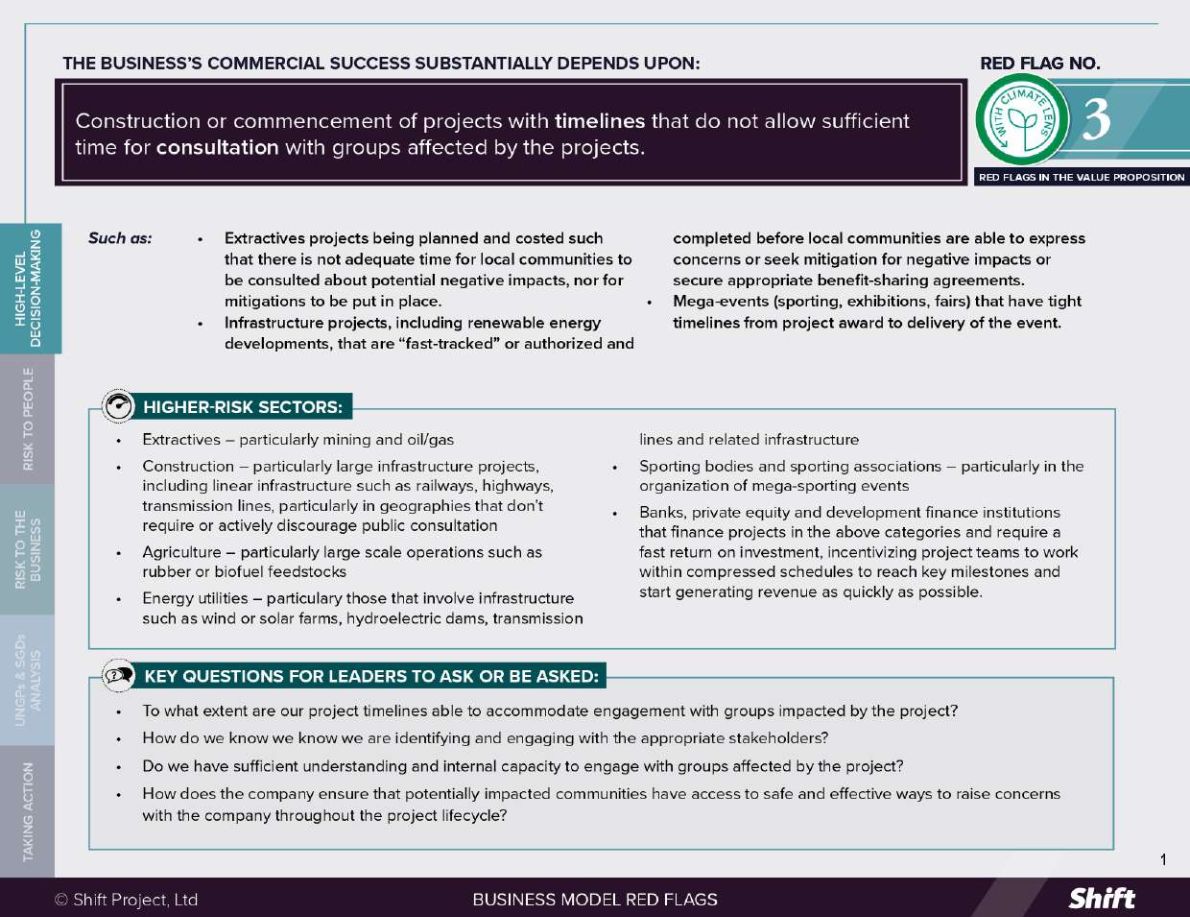

RED FLAG # 3

The business’s commercial success substantially depends upon construction or commencement of projects with timelines that do not allow sufficient time for consultation with groups affected by the projects.

For Example

- Extractives projects being planned and costed such that there is not adequate time for local communities to be consulted about potential negative impacts, nor for mitigations to be put in place.

- Infrastructure projects, including renewable energy developments, that are “fast-tracked” or authorized and completed before local communities are able to express concerns, seek mitigation for negative impacts or secure appropriate benefit-sharing agreements.

- Mega-events (sporting, exhibitions, fairs) that have tight timelines from project award to delivery of the event.

Higher-Risk Sectors

- Extractives – particularly mining and oil/gas

- Construction – particularly large infrastructure projects, including linear infrastructure such as railways, highways, transmission lines, particularly in geographies that don’t require or actively discourage public consultation

- Agriculture – particularly large-scale operations such as rubber or biofuel feedstocks

- Energy utilities – particularly those that involve infrastructure such as wind or solar farms, hydroelectric dams, transmission lines and related infrastructure

- Sporting bodies and sporting associations – particularly in the organization of mega-sporting events

- Banks, private equity and development finance institutions that finance projects in the above categories and require a fast return on investment, incentivizing project teams to work within compressed schedules to reach key milestones and start generating revenue as quickly as possible.

Questions for Leaders

- To what extent are our project timelines able to accommodate engagement with groups impacted by the project?

- How do we know we are identifying and engaging with the appropriate stakeholders?

- Do we have sufficient understanding and internal capacity to engage with groups affected by the project?

- How does the company ensure that potentially impacted communities have access to safe and effective ways to raise concerns with the company throughout the project lifecycle?

How to use this resource. ( Click on the “+” sign to expand each section. You can use the side menu to return to the full list of red flags, download this Red Flag as a PDF or share this resource. )

Understanding Risks and Opportunities

Risks to People

|

Research in the mining sector shows that often there is a tension between “technical time” – the time needed for the construction or completion of a project – and “social time” – the time needed to address community concerns related to the project. Even when companies see the importance of consulting affected communities, their approaches are not always effective.

Even companies or financial institutions that have policy commitments to community engagement can sometimes have business models that depend on project timelines which do not allow for sufficient time for consultation with affected stakeholders. The low carbon transition is leading to a growth in business models that carry this risk. The urgency of the global climate challenge and the imperative of transitioning as quickly as possible to a lower carbon economy have, in certain cases, resulted in states and companies “fast-tracking” development of transition mining projects and/or low emissions energy projects. A 2022 study found that, in the case of energy transition minerals, not only is there a risk that procedural safeguards for consultation and consent will be diluted, but also that the future supply of energy transition minerals will exacerbate social inequalities in already vulnerable locations. For example, an estimated 54% of energy transition minerals are located on or near Indigenous Peoples’ land. An Amnesty International study looking at the impact of cobalt and copper mining expansions in the DRC found that many communities around the key mining locations have endured significant impacts as a result of energy transition mineral mining, including the absence of any community consultation and forced evictions. On the renewable energy front, several jurisdictions, including India, South Africa, and Japan, have adopted legislation intended to speed up project development. Unfortunately, such legislation often exempts project companies from or reduces requirements for prior consultations with communities and/or enables forced expropriation of land. A business model focused on expedited timelines that don’t allow for sufficient consultations, can lead to the following risks to people:

|

Risks to the Business

|

Business models that substantially depend on project timelines which do not allow for sufficient time for consultation with affected stakeholders can lead to the following risks to companies: Financial, Legal and Reputational Risks:

Operational Risks Linked to Social Unrest:

|

What the UN Guiding Principles say

-

Companies can cause adverse human rights impacts when they fail to carry out meaningful consultation with affected stakeholders and their actions negatively affect human rights. A failure to allow time for the conduct of Free, Prior and Informed Consultation (FPIC) with affected Indigenous communities, or to ensure that FPIC with these communities has been conducted by others, is itself a breach of Indigenous people’s human rights. More generally, a company may cause human rights impacts when it sets timescales which preclude consultation with affected communities as part of a risk assessment and mitigation process, and the company’s actions then have negative impacts on communities such as forced displacement, depriving communities of access to water, food or livelihoods or preventing them of entering cultural sites.

-

Organizations (including companies, mega-event organizers and financial institutions) can contribute to adverse human rights impacts when their business models create demand for speed in the delivery of projects by third parties, and the demand for speed prevents third parties from carrying out meaningful consultation with local communities, resulting in adverse human rights impacts.

Possible Contributions to the SDGs

Addressing impacts on people associated with this red flag can contribute to ensuring responsible, inclusive and participatory and representative decision-making at all levels (Target 16.7 of SDG 16: promoting peaceful and inclusive societies).

The results of consultation with groups affected by projects can enable companies to better understand and mitigate risks to people, which can contribute to the following SDGs:

-

SDG 1: End poverty in all its forms everywhere. Meaningful consultation can help ensure that people – particularly vulnerable communities – have equal rights to economic resources, including ownership and control over land.

-

SDG 2: Zero hunger. Meaningful consultation can help agricultural productivity and incomes of small-scale farmers, in particular women and Indigenous communities, including through secure and equal access to land and productive resources.

-

SDG 3: Good health and wellbeing. Meaningful consultation can help protect stakeholders’ health by preventing negative impacts such as pollution of soil, air or water sources, or impacts from poor working conditions such as fatigue, stress and accidents.

-

SDG 6: Clean water and sanitation. Meaningful consultation can help prevent pollution of water sources.

-

SDG 7: Affordable and Clean Energy. Meaningful consultation can help to ensure that clean energy projects are advanced swiftly and with public support.

-

SDG 13: Climate action. Meaningful consultation can help to ensure that the transition to a lower carbon economy is fast because it is fair.

Taking Action

Due Diligence Lines of Inquiry

-

Do we understand the local context and the potential ways in which our project can impact on people?

-

Do we have a process to sensitize our staff about local issues and the local context?

-

Do we know which stakeholders we need to consult and how to structure the consultations to make them meaningful and accessible?

-

Have any vulnerable or historically marginalized groups been identified in or around the project site?

-

Do we know if groups that self-identify as Indigenous Peoples are impacted by the project and, if so, do we understand how that will impact project timelines?

-

Do those responsible for community engagement have the requisite skills and experience for engaging with affected stakeholders, including Indigenous Peoples?

-

Do our project plans allow sufficient time for consultation to take place?

-

Do we actively support community relations managers to carry out the consultations?

-

Does advice from community relations managers get reported to the executive?

-

Are we prepared to review the project plan based on insights from the consultations?

-

Do we measure and/or have we accounted for the cost of conflict with local communities?

Mitigation Examples

|

* Mitigation examples are current or historical examples for reference, but do not offer insight into their relative maturity or effectiveness.

|

Alternative Models

-

The Indigenous Peoples’ Rights International (IPRI) and the Business & Human Rights Resource Centre are making the case for a renewable energy transition that centers Indigenous Peoples’ rights, interests and prosperity, as determined by them, in pursuit of a global transition that is fast because it is fair and sustainable. Among other resources, the report outlines emerging benefit-sharing modalities with real-world examples of where and how they are being deployed, as well as recommendations for regulators, renewable energy developers and financial institutions.

-

In Alaska, the Red Dog Mine operation, which sources nearly 5% of global zinc supply, was developed through an operating agreement between Teck Resources and 15,000 Iñupiat shareholders of NANA Corporation.

-

One of the largest seafood companies in the southern hemisphere is 50% owned on behalf of the Māori people of New Zealand and 50% by the Japanese company Nissui.

Other Tools and Resources

General

-

Shift, UN Global Compact Netherlands & Oxfam. Doing Business with respect for human rights – Chapter 3.7: Stakeholder Engagement – Making it Meaningful

-

Shift (2018) Engaging Affected Stakeholders: Evaluating the quality of processes for company-community engagement

-

Investor HREDD Precision Tools (2025) Stakeholder Engagement Guide (beta)

-

Task Force on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (2023) Guidance on Engagement with Indigenous Peoples, Local Communities and affected stakeholders

-

Science-based Targets Network (2024) Stakeholder engagement and science-based targets for nature

-

UNEP Finance Initiative (2025) Human Rights Toolkit: Infrastructure

-

Buhmann, Karin et al. (2024) The Routledge Handbook on Meaningful Stakeholder Engagement

-

Amazon Watch (2023) Respecting Indigenous Rights: An Actionable Due Diligence Toolkit for Institutional Investors

-

Equator Principles (2021) To Enhance Access to Effective Grievance Mechanisms and Enable Effective Remedy

-

Equator Principles (2020) Guidance Note: Evaluating Projects with Affected Indigenous Peoples

-

IFC (2007) Note on ILO Convention 169 and the private sector

Sector specific:

-

Business and Human Rights Resources Centre (2024) Stop and listen: Pathways to meaningful engagement with rightsholders in the global rush to mine for transition minerals

-

Business and Human Rights Resource Centre (2024) Exploring Shared Prosperity: Indigenous leadership and partnerships for a just transition.

-

IIED paper (2016) Meaningful community engagement in the extractives sector

Citation of research papers and other resources does not constitute an endorsement by Shift of their conclusions.

Business Model Red Flags

Business Model Red Flags  Tool for Indicator Design

Tool for Indicator Design