The Indicator Design Tool provides a simple way for business practitioners –and other stakeholders, to develop targets and indicators focused on better outcomes for people.

The Indicator Design tool helps users learn about what is working and why in order to make evidence-based decisions on how to allocate resources, adjust programs and ultimately, deliver improved outcomes for workers, consumers and communities. The Tool can be applied to a wide range of efforts aimed at preventing, mitigating and remediating human rights impacts, regardless of industry, operating context or human rights issue.

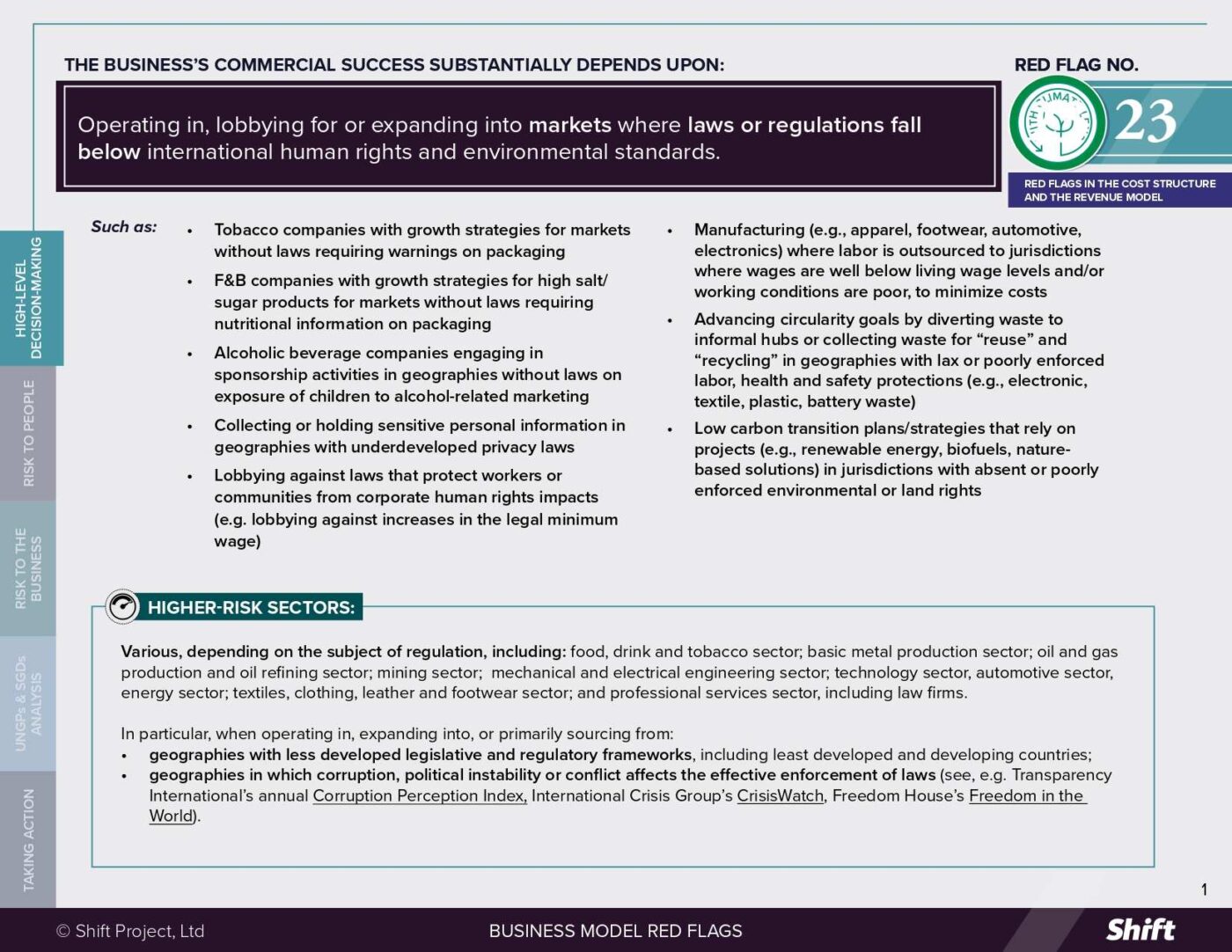

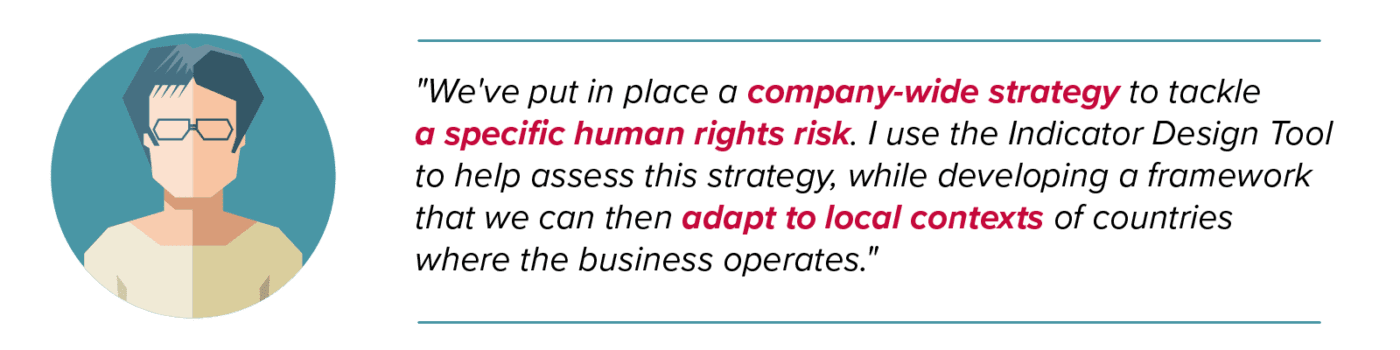

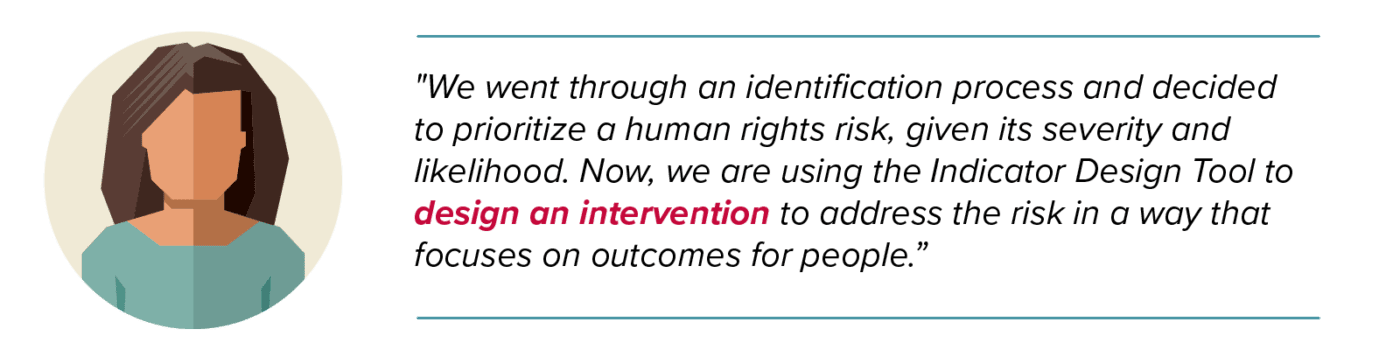

Here are a few hypothetical examples:

NOTE: These quotes are fictitious and are offered with the purpose of illustrating potential ways in which the Indicator Design Tool can be used.

The Methodology

At the core of this tool is an approach known as Theory of Change thinking: a well-established monitoring and evaluation practice from the fields of international development and public policy.

About Theory of Change

About Theory of Change

Theory of change models follow an “if/then” logic along the sequence from inputs to activities, outputs, outcomes and impacts: if these inputs are in place, then we can do these activities; if we do these activities, we will deliver these outputs, and so on. This is a simple way of thinking that addresses the, often unexamined, space between what we do (activities, programs, initiatives) and the ultimate goals we want to achieve. It forces clarity on what is required at each step to achieve results.

A theory of change model stretches us to think about indicators and information needs at all stages in an intervention, and the relationship between them. The resulting inter-related set of indicators and real-word data then allows us to see the actual relationships of cause and effect across the theory of change. This provides an evidence base to identify how our activities relate to the change we are trying to deliver.

The theory of change framework used in the Indicator Design Tool is shown in the diagram below. This framework has been adapted from traditional theory of change models to suit the realities of business and human rights challenges.

This version of the theory of change adapts the typical model in three ways:

We’ve added ‘practices and behaviors’ between ‘outputs’ and ‘outcomes’

It can be relatively easy to measure the outputs of an activity such as knowledge gained by participants in a training event, or corrective actions identified through an audit process. Both activities may aim to improve the treatment of workers in factories, but will by no means necessarily achieve that outcome. Yet measuring the actual outcome for workers consistently over time can be difficult and resource-intensive.

The category of ‘practices and behaviors’ provides a midpoint of evaluation that focuses on the desired changes in human behavior. For instance, it shows whether knowledge acquired or a corrective action identified actually changes what gets done in the workplace and how. This is a much stronger indication of whether workers are likely to be treated better than we get from outputs alone. Practices and behaviors can often be more easily and consistently measured than can the ultimate outcomes themselves. Once a clear and replicable connection between practices/behaviors and outcomes is established, they can be valuable and scalable indicators of likely outcomes.

The focus is on “outcomes for people”, not on general impacts.

This model omits the category of ‘impact’ that is often placed after ‘outcomes’, and represents a higher-level societal benefit that is desired over a longer period of time, such as ‘increasing median wages by 20% in the next 15 years’. It can be helpful to have this kind of higher-level impact in mind when thinking about a theory of change. However, given the number of factors involved, it is particularly difficult to evaluate how one company, or even industry, has contributed to it. Therefore, it did not seem useful to include in this model.

We’ve emphasized the distinction between ‘outcomes for people’ and ‘outcomes for business’

The aim of responsible business initiatives and practices is to improve outcomes for people (and/or planet). However, it can be helpful to show where these efforts also bring benefits to the business itself – for example in cost savings, reputational improvements, or new business opportunities. This builds the case for embedding these practices routinely into how business gets done. At the same time, positive outcomes for business are not necessarily positive outcomes for people. For example, a company may eradicate forced labor from its own supply chain, but the workers concerned may simply have been pushed into other jobs in which conditions of forced labor persist. This distinction, therefore, requires us to evaluate the two types of outcomes separately.

This tool alone won’t work if you don’t engage with stakeholders

Stakeholder engagement is a critical aspect of using this tool successfully. Stakeholders should include internal issue owners and subject-matter experts; affected stakeholders and/or their legitimate representatives; and where appropriate, companies (such as peers, suppliers, partners or customers) that are an integral part of achieving the outcomes you are seeking to achieve.

Why engage with stakeholders?

Why engage with stakeholders?

Each company will decide the most effective and robust way to do this, for example: via one-to-one consultations, workshops on specific parts of the process, or sharing draft content for inputs. Regardless of the method used, engagement will tend to offer numerous benefits:

- Informing new ideas about how to achieve change by building on the company’s own experience, and leading practices of other companies.

- Understanding what needs to change for the better from the perspective of affected groups, as well as their views on how that change might be achieved.

- Establishing a full and complete understanding of contextual factors that will impact the effectiveness of interventions, including internal organizational dynamics such as incentives, and local legal or cultural issues;

- Building internal and external buy-in for indicators and support with data collection, and

- Increasing the chances that stakeholders will view disclosure of data about progress and impact as credible.

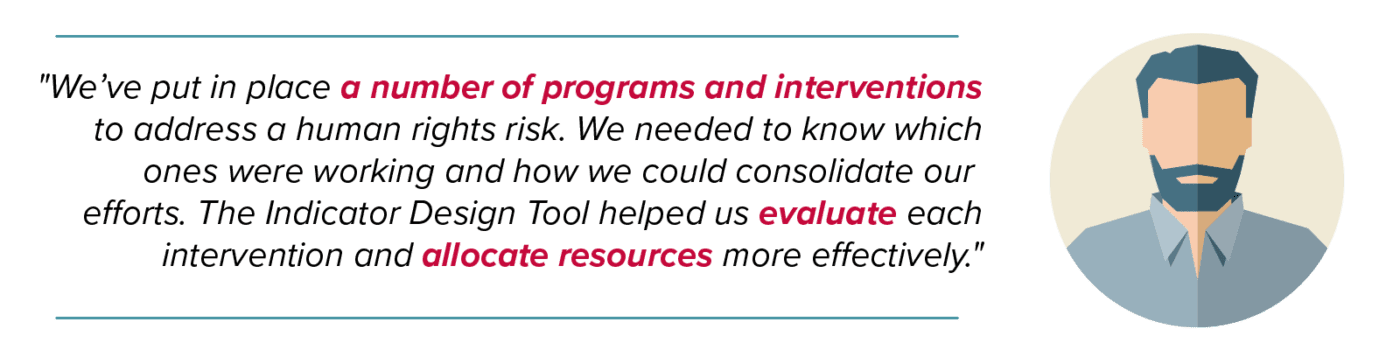

Business Model Red Flags

Business Model Red Flags  Tool for Indicator Design

Tool for Indicator Design