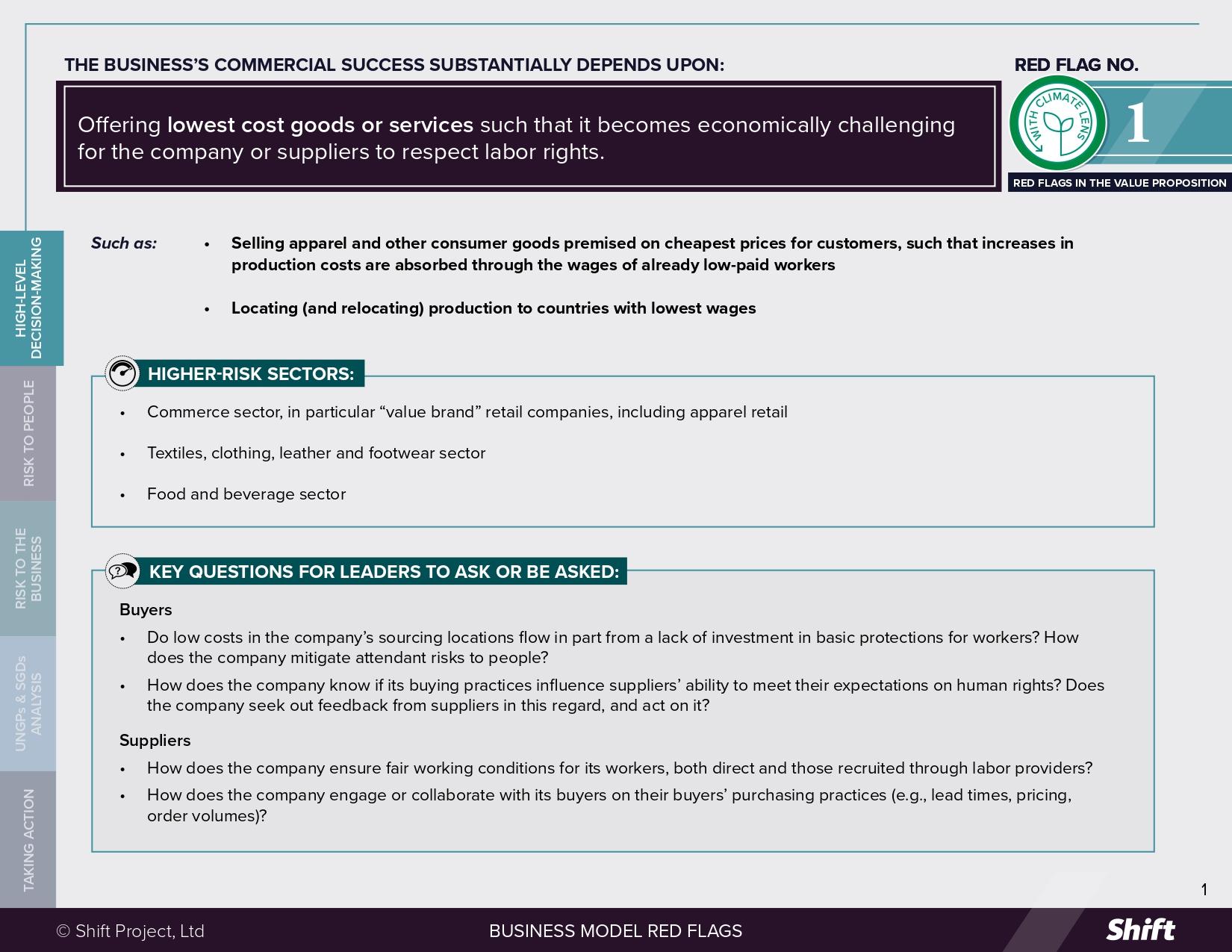

RED FLAG # 1

The business’s commercial success substantially depends upon offering lowest cost goods or services such that it becomes economically challenging for the company or suppliers to respect labor rights.

FOR EXAMPLE

- Selling apparel and other consumer goods premised on cheapest prices for customers, such that increases in production costs are absorbed through the wages of already low-paid workers

- Locating (and relocating) production to countries with lowest wages

HIGHER-RISK SECTORS

- Commerce sector, in particular “value brand” retail companies, including apparel retail

- Textiles, clothing, leather and footwear sector

- Food and beverage sector

Questions for Leaders

Buyers

- Do low costs in the company’s sourcing locations flow in part from a lack of investment in basic protections for workers? How does the company mitigate attendant risks to people?

- How does the company know if its buying practices influence suppliers’ ability to meet its expectations on human rights? Does the company seek out feedback from suppliers in this regard, and act on it?

Suppliers

- How does the company ensure fair working conditions for its workers, both direct and those recruited through labor providers?

- How does the company engage or collaborate with its buyers on their buyers’ purchasing practices (e.g., lead times, pricing, order volumes)?

How to use this resource. ( Click on the “+” sign to expand each section. You can use the side menu to return to the full list of red flags, download this Red Flag as a PDF or share this resource. )

Understanding Risks and Opportunities

Risks to People

- Where the business model is premised on securing cheapest prices for customers (as opposed to other differentiating factors such as quality or service), retail prices often remain constant or reduce, even when costs of production, raw materials or demands for high-speed or just-in-time delivery increase. In such cases the company may use its purchasing power to place heavy price pressure on suppliers working on narrow margins, such that costs are passed onto the most vulnerable people in supply chains – such as factory workers, including migrant workers, women workers, producers and small-holder farmers – affecting their livelihoods and those of their families. (Right to fair/living wage; Right to adequate standard of living)

- Suppliers under excessive price pressure may be incentivized to demand excessive overtime from workers, not pay or suppress wages or overtime, or not provide safe working conditions. Risks are exacerbated when the company provides little or no commitment to long-term sourcing, disincentivizing investment in improving working conditions. (Right to just and favorable conditions of work; Right to Health)

- Risks are greatest where the company locates (and relocates) production to countries where minimum or industry wages leave workers in poverty and workers lack adequate protections in law or in practice. These same countries are then incentivized to keep labor costs low to maintain competitive advantage and continue to attract foreign investment from multinational companies. (Right to an adequate standard of living; Right to fair/living wage)

- Business models centered on delivering low-cost goods and services often impose intense cost pressures on suppliers, leaving little room for investments in worker protections or sustainable practices. As the world transitions to a lower carbon economy, many companies are facing pressure to decarbonize across their value chains. Buyers’ supply chain emissions reduction targets can exacerbate the inherent pressures of the low-cost goods and services business model, when responsibility for emissions compliance, including associated costs, are passed on to suppliers without guidance or financial support for making the necessary emissions reductions. To implement low carbon workflows or investments to satisfy buyers’ emissions requirements in an already cost-constrained environment, suppliers may reduce workers’ wages, require excessive overtime, or underinvest in workplace safety, particularly in regions with weak labor protections. Other buyers’ decarbonization strategies that could negatively impact supply chain workers if not managed appropriately, include:

- shifting sourcing patterns (e.g., supply chain consolidation or diversification, “agile” supply chains, or nearshoring/reshoring);

- automating or introducing new low carbon technology or machinery, and;

- circular economy measures (e.g., reducing production, reducing waste, renewable or recycled materials).

- Further, as the physical impacts of climate change intensify — including rising temperatures and more frequent extreme weather events, such as storms and flooding — workers in supply chains face escalating risks, particularly in labor-intensive sectors like fashion & textiles, and food and beverage. In environments where employers, under pressure to keep production costs low, are unwilling or unable to invest in climate change adaptation measures, such as heat adapted conditions, adjusted working hours, or paid leave during extreme weather, workers endure growing exposure to heat stress, dehydration, or accidents. Productivity losses – already shown to be linked to extreme heat – impact employers’ costs and output potential, as well as workers’ wages and job security. A study by the Global Labor Institute found that without significant investment in climate change adaptation, physical climate impacts on workers in the fashion sector will only get more pronounced as global temperatures rise, with increasingly devastating impacts on workers and job availability in major production hubs like Vietnam and Bangladesh. These impacts will be particularly acute for groups that are already more economically and socially vulnerable, such as migrant workers, women, or smallholder farmers. Thus, failure to adapt or maladaptation has the potential to further exacerbate the negative risks to people inherent in this business model.

Risk to the Business

- Financial, Reputational, and Operational Risks: Companies operating in a hyper flexible sourcing context (i.e. where sourcing can move quickly and easily between multiple locations) may benefit from lowest prices, but face reputational risks linked to the ease of exploitation of low-skilled, low-paid workers in such sourcing geographies with minimal protections for them. The short-term and remote nature of many supplier relationships can reduce buyers’ leverage to do anything about abusive behaviors in their supply chain when they are highlighted by civil society, consumers or their own audits.

- In October 2022, a UK documentary alleged exploitative labor practices in Shein‘s supply chain. The allegations highlighted systemic issues within the ultra-fast fashion model, which emphasizes rapid production and low costs, often at the expense of worker welfare. In response, Shein pledged a $15 million investment over three to four years to improve working conditions and oversight. Despite these efforts, subsequent reports, including Shein‘s 2023 Sustainability Report, disclosed ongoing concerns, such as instances of child labor and excessive working hours within its supply chain. These findings have continued to attract scrutiny from regulators and human rights organizations (see investor briefing here), impacting Shein’s attempts to pursue public listings in major markets.

- In 2020, a UK-based low cost online retailer, Boohoo Group, faced significant backlash after reports emerged of labor rights abuses in its UK-based supply chain. The scandal led to a sharp decline in Boohoo‘s share price (wiping more than GBP1.5B off its valuation over a week-long period) and prompted several retailers to drop its products. The company commissioned an independent review, which confirmed the allegations. While there has been some follow-up to address the issues identified, the company faces ongoing criticism regarding systemic labor violations in their supply chain. Further, in May 2024, 49 of its investors filed a legal claim seeking GBP100M in damages alleging the company made “untrue or misleading statements and failed to disclose material information” about the matter to the market.

- In July 2020, Violet Apparel, a Cambodian factory owned by Ramatex Group, closed “with less than one week’s notice”, terminating 1,284 workers without paying USD1.4 million in legally mandated severance. Although, a workers rights organization alleges that Nike-branded products were produced there, Nike maintains it hasn’t sourced from Violet Apparel since 2006. However, more than 50 human rights groups and over 70 investors have urged Nike to ensure compensation, alleging failures in supply chain oversight and due diligence.

- An increasing number of institutional investors view payment of a living wage as a material investment factor linked to financial, reputational, and operational performance. In Europe, the Platform Living Wage Financials coalition—comprising 22 financial institutions overseeing over €7 trillion in assets—posits that paying a living wage can reduce operational risks, particularly in company value chains. Meanwhile, UK investors such as Scottish Widows, Axa and Aviva Investors have recently backed shareholder resolutions linking living wage commitments with long-term business resilience, recognizing that not paying a living wage poses risks to talent retention, productivity, and shareholder value.

- Tragedies affecting workers in the supply chains of global brands that benefit from low cost production implicate entire industries: in the wake of the Rana Plaza collapse, companies sourcing from Bangladesh that did not have garments produced in at Rana Plaza were equally affected by campaigns that focused on the complicity of the “entire industry” in conditions leading to the tragedy.

- Operational, Regulatory and Reputational Risks: Companies may find themselves unable to guarantee traceability as suppliers under extreme price pressure often sub-contract production, leading to a longer, less transparent and less controllable supply chain.

- In December 2024, a report by China Labor Watch revealed that coffee farms supplying Nestlé and Starbucks were engaging in labor practices that violated both companies’ sourcing standards. The investigation uncovered that the drive to meet demand for lower cost coffee products resulted in suppliers sub-contracting from smaller, uncertified “ghost farms” at which there were recorded instances of child labor, excessive working hours, lack of formal contracts, and inadequate safety measures. This resulted in operational, regulatory and reputational risks for Nestle and Starbucks who were: (i) accused of contravening their own ethical sourcing standards, (ii) at risk of non-compliance with supply chain regulation in key markets, and (iii) making headlines in major news outlets.

- Financial Risk and Business Opportunity Risk: Data shows consumer concerns about lowest price apparel goods, for example, and an increase in the number of consumers, particularly younger consumers and higher income consumers, who state that they would be willing to pay more for ethically sourced, sustainable goods. This suggests that there could be important shifts in consumer preferences that will impact lowest cost goods. Failure to address this may have financial implications including in the form of missed opportunities to adapt.

- Financial and Operational Risks: The Global Labor Institute at Cornell University published a study mapping out the supply chains of six unidentified low cost global apparel brands operating in Bangladesh, Cambodia, Pakistan and Vietnam. The study found that all six would be hit materially by extreme heat and flooding, which could “erase USD 65 billion in apparel export earnings” by 2030, as workers struggle under high temperatures and factories close.

- Regulatory Risk: Operating on a low cost goods and services business model can be associated with regulatory risk. Regulation has been tabled in some jurisdictions to reduce waste associated with low cost goods. Some examples include:

- In 2025, France’s Senate approved a law seeking to curb advertising by companies selling garments with extremely rapid turnover, low cost and short lifespans, with enforcement now awaiting passage through a joint committee and presidential signature. It targets all media advertising—including digital, traditional, and influencer ads—and is proposed to take effect on January 1, 2026.

- Noting, among other things, that “garment workers face the brunt of the [fast fashion] industry’s race to the bottom”, lawmakers introduced legislation during New York’s 2025/26 legislative session seeking to mandate environmental and social due diligence for the apparel and footwear sectors for companies with over $100 million in global revenue, requiring supply chain transparency and due diligence, with penalties for non-compliance.

- The EU has agreed on binding rules that force brands—especially low-cost, fast-fashion producers—to finance textile waste collection, sorting, and recycling under an extended producer responsibility system, with fees targeting ultra-fast production. From January 1, 2025, all EU member states are required to implement separate textile collection, while digital passports and stricter eco-design standards further mandate durability, recyclability, and supply-chain transparency and traceability.

What the UN Guiding Principles Say

The UNGPs note that companies should “strive for coherence between their responsibility to respect human rights and policies and procedures that govern their wider business activities and relationships [including] …. procurement practices” (Principle 16, Commentary).

Where the incentives for impacts are embedded in the buying company’s purchasing practices, it may systematically rewards buyers for placing extreme pressure on suppliers, and punish those that invest in protections for workers in ways that raise their costs (and therefore prices to the buying company). In such circumstances, the company may be considered to contribute to impacts on supply chain workers. Similarly, where the company executes a strategy to benefit from wages below a living wage, including, in some cases, by lobbying against minimum wage increases, it may contribute to the impacts experienced by workers.

Possible contributions to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

Addressing impacts to people associated with this red flag can contribute to, inter alia:

-

SDG 1: End Poverty in All its Forms Everywhere, in particular

-

Targets 1.1 and 1.2 on eradicating extreme poverty and reducing by half the number of people living in poverty (according to national definitions).

-

-

SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth, in particular

-

Target 8.8 on protecting “labor rights and promot[ing] safe and secure working environments for all workers, including migrant workers, in particular women migrants, and those in precarious employment.”

-

-

SDG 10: Reducing inequalities within and between countries

This goal becomes relevant as profit margins and returns are concentrated at the buyer/investor level, with less and less value making it into the pockets of the poorest in the supply chain

-

SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production, in particular

-

Target 12.5 on substantially reducing waste generation through prevention, reduction, recycling and reuse.

-

Taking Action

Due Diligence Lines of Inquiry

For Buyers:

-

Do our contracting/tendering processes unduly incentivize cost cutting or disincentivize supplier investment in rights-related improvements (e.g. annual bidding for contracts; procurement decisions based on lowest-cost alone). How do we ensure that lowest price bids reflect greater efficiencies rather than externalization of costs onto supply chain workers? Have we considered the five principles of responsible purchasing that Better Buying has identified that affect a supplier’s ability to provide good working conditions?

-

How do we incentivize and reward our in-house buyers and how do they perceive the factors on which they are judged to succeed? Do we consider factors other than lowest price (e.g. relationship and capacity building; adherence to sustainability codes etc.)?

-

Do our in-house buying staff have sufficient knowledge, incentives and support to assess how and when their decisions will place human rights at risk, and to know from whom to seek assistance when they do?

-

How do we know whether our buyers follow our processes, rules or guidelines in practice when engaging or contracting with suppliers?

-

Do we engage with our suppliers in ways that help us understand how far they can go to meet our demands while still respecting the rights of their workers? Do we work with suppliers in countries of production to increase worker protections?

-

Do we take a short term, transactional approach to supply chains or do we develop supply chain partnerships?

-

How are we engaging with our industry peers to uphold human rights in our shared supply chains, recognizing this is a pre-competitive issue? Are we engaging in multi-stakeholder initiatives that are actively working to improve wages and livelihoods in the supply chain?

-

How have we engaged with our suppliers on our GHG emissions reduction strategies and the potential implications those strategies could have for supply chain workers?

-

How are we integrating the potential impacts on supply chain workers of physical climate change impacts (e.g., extreme heat and flooding) into our expectations for suppliers?

For suppliers:

-

Do we have sufficient knowledge, incentives and support to assess how and when buyer decisions will place human rights at risk?

-

Do we engage regularly with our buyers to help them understand the implications of their demands on respecting the rights of workers?

-

Do we provide constructive feedback to buyers on purchasing practices that have negative impacts on workers, either through direct engagement or through buyer ratings services?

-

How have we explored using legislative requirements (e.g., from the EU) to engage with buyers on their purchasing practices and changes that can support more effective due diligence?

-

Do we understand the potential impacts of buyers’ climate-related emissions reduction requirements on our workforce and have we communicated them to the buyers?

-

How have we factored physical climate change impacts (e.g., increasing frequency, duration and severity of extreme heat) into our operations and expectations of our workers?

Mitigation Examples

*Mitigation examples are current or historical examples for reference, but do not offer insight into their relative maturity or effectiveness.

-

Increasing leverage through collaboration: Given the systemic nature of the issues, collaborating with other companies may be one of the most effective ways to affect change. For example:

-

ACT is a coalition of over 40 global apparel brands, working alongside IndustriALL Global Union to secure living wages through industry-level collective bargaining. Building on the original Memorandum of Understanding, brands are committed to ensuring their purchasing practices support higher wages via five key commitments—including itemized labor costs, fair terms, responsible exit strategies, and mandatory training—underpinned by the ACT Labour Costing Protocol and a robust Accountability & Monitoring Framework. In May 2024, ACT and IndustriALL signed bilateral support agreements focused on wage improvements and better working conditions in the Cambodian garment and footwear sector.

-

Launched in 2023, the UN Global Compact Forward Faster initiative calls on companies to commit to ensuring 100% of their employees earn a living wage by 2030. Participating companies must also develop joint action plans with suppliers to extend fair wage practices through their supply chains. Early steps include wage assessments, pilot pay adjustments, and public reporting to drive sector-wide accountability. Over 1,400 businesses, including JA Solar and Adiantes, have joined with measurable, time-bound wage targets.

-

-

Understanding and addressing pressures on farmers and suppliers: The Farmer Income Lab, launched by Mars, with Dalberg and Wageningen universities and Oxfam USA, is a collaborative effort to identify ways to increase smallholder farmers’ incomes – beginning with Mars’ supply chains in developing countries – and to understand how to create positive outcomes for farmers at scale.

-

Focusing on purchasing practices: The Better Buying Institute (recently acquired by Cascale) is an organization that provides tools and research to help companies improve purchasing practices in ways that support fairer, more sustainable supply chains. Better Buying’s anonymous supplier feedback system enables suppliers to confidentially evaluate their customers’ purchasing practices across areas such as planning and forecasting, payment terms, and order changes, which provides structured and candid insights that might not otherwise be shared openly, helping buyers and suppliers to identify where practices may create unnecessary cost pressures or labour rights risks. For example, Under Armour has used these supplier evaluations to address issues such as forecast accuracy, production timelines, and vendor training. SanMar, a large US-based wholesale apparel supplier, has publicly shared its Better Buying scores to demonstrate its commitment to transparency and accountability. The company has also used the supplier feedback to refine its forecasting processes, reduce last-minute order changes, and improve communication with manufacturing partners.

-

Exploring customer willingness to pay for better practices: In April 2024, as part of its participation in the Tony’s Open Chain initiative, Waitrose introduced a small yellow “Tony’s Open Chain” label on its private-label chocolate bars and raised prices by about 10%, which the company reported having had a positive impact on its sales, at least in the early weeks of its sales. Member brands of the Tony’s Open Chain collaboration— which includes Waitrose, Aldi, and Ben & Jerry’s—commit to paying a living-income premium above Fairtrade prices to bridge income gaps for cocoa farmers. The initiative is reporting early positive outcomes related to reduced child labor rates and reduced deforestation.

-

Partnering with expert organizations to pilot new approaches: In 2021, Brands Fashion, in partnership with GIZ and Fairtrade, piloted a living wage initiative covering around 1,000 textile workers in India. The project certified the company’s entire supply chain under the Fairtrade Textile Standard, making it the first apparel firm to achieve this. These 1,000 workers were employed in selected certified factories where Brands Fashion had established relationships and sufficient influence to implement wage increases, worker training, and democratic representation.

-

Recognizing and acting upon the correlation between human rights and overall supplier performance: Research by Business Fights Poverty and Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership, supported by Shift, has highlighted a direct correlation between how a supplier treats their workers and the overall performance of that supplier on a range of factors. Research interviews with buyers identified a clear link between the quality and reliability of suppliers, and the working conditions and levels of pay received by workers in supplier factories. As such, mitigating risks to supply chain workers can help to mitigate other risks associated with supplier performance and create the opportunity for improved business performance. To measure this correlation, the procurement teams of some leading companies now benchmark and track the corporate payback from investments in responsible purchasing practices.

-

Integrating extreme heat adaptation actions into supplier codes of conduct: Levi’s’ 2025 Supplier Code of Conduct addresses the brand’s expectations for workplace health and safety across its strategic suppliers and has explicit expectations for managing extreme heat, which specify requirements such as the provision of potable water near work areas, shaded or cooled rest zones, and defined work/rest schedules.

-

Contributing to a regulatory environment that enables respect for rights: In 2014, eight apparel brands wrote to the Cambodian deputy prime minister and the chairman of the local Garment Manufacturers Association to say they were “ready to factor higher wages” into their pricing.

Alternative Models

In the US, the Fair Food Program, established by The Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW) in 2011, brings together the CIW, farmworkers on participating farms, farmers and retail food companies. Among the many facets of the program is a “penny per pound” premium that is paid by participating buyers on top of the regular price paid for tomatoes or other covered products. The premium is then passed through by farmers as a bonus on worker’s paychecks, which are monitored by the Fair Food Standards Council, the program’s independent monitoring body. See further from Shift here.

Alternative models can focus on differentiating through quality and/or ethical and transparent sourcing. Various “slow” movements (“slow food,” “slow fashion”) etc. offer products in which the value proposition incorporates fair, transparent and sustainable sourcing and manufacturing, with a focus on durability and quality.

The ETI highlights examples in the apparel industry, including:

-

Nudie Jeans (higher priced but ethically sourced and more durable jeans)

-

People Tree (apparel produced using organic cotton, sustainable materials and traditional skills that support rural communities)

-

“Crowd farming” (consumers receive food directly from source and sponsor the cultivation of raw materials)

ASKET is a Swedish menswear company that operates on the premise of a permanent, season-less collection. They focus on producing only “essential” garments that are continually refined, reducing overproduction and quick style turnover. They sell directly to consumers at full cost transparency—detailing origin, factory working conditions, and itemized pricing—with the aim of shifting focus from cheap volume to long-term value. ASKET generates around $10 million in annual sales by relying on a transparent, durable-focused business model that also emphasizes repair and resale programs to support a full lifecycle approach and to differentiate from a low-cost, disposable fashion model.

Tony’s Chocolonely prioritizes ethical sourcing, fair labor practices, and long-term sustainability over price minimization. The company implements five core sourcing principles: 100% traceable beans, paying higher prices to farmers, empowering farmers to have greater control and bargaining power in the supply chain, establishing long-term purchase agreements, and supporting improvements in bean quality and productivity. The company also introduced a feature it refers to as “Mission Lock,” which is a legal structure focused on maintaining the company’s ethical mission, preventing any changes to its core values and sourcing principles.

Other tools and resources

-

Shift (2025) Living Wage Accounting Model and Progress Tool

-

Cascale’s Better Buying programme

-

Business and Human Rights Resource Centre (2025) The missing thread: Workers absent from fashion companies’ climate plans

-

Fashion Revolution (2024) What Fuels Fashion?

-

Global Labor Institute (2023) Higher Ground? Reports 1 & 2.

-

Ethical Trading Initiative (2024) Extreme heat: Risks for workers in global supply chains

-

Ethical Trading Initiative (2025) Flooding: Risks for workers in global supply chains

-

Ethical Trading Initiative (2025) Common Principles for Responsible Purchasing Practices in Manufacturing Industries

-

Ethical Trading Initiative (2024) Common Principles for Responsible Purchasing Practices in Food

-

Global Deal (2024) The Global Deal Flagship Report

-

Reinecke, J., Donaghey, J., Bocken, N. and Lauriano, L. (2019) Business Model and Labour Standards: Making the Connection Ethical Trading Initiative, London

-

Fair Labor Association (2020) Fair Compensation Strategy

-

IDH Roadmap on Living Wages: A Platform to Secure Living Wages in Supply Chains

Case example

-

Rana Plaza Factory Fire (IHRB)

Citation of research papers and other resources does not constitute an endorsement by Shift of their conclusions.

Business Model Red Flags

Business Model Red Flags  Tool for Indicator Design

Tool for Indicator Design