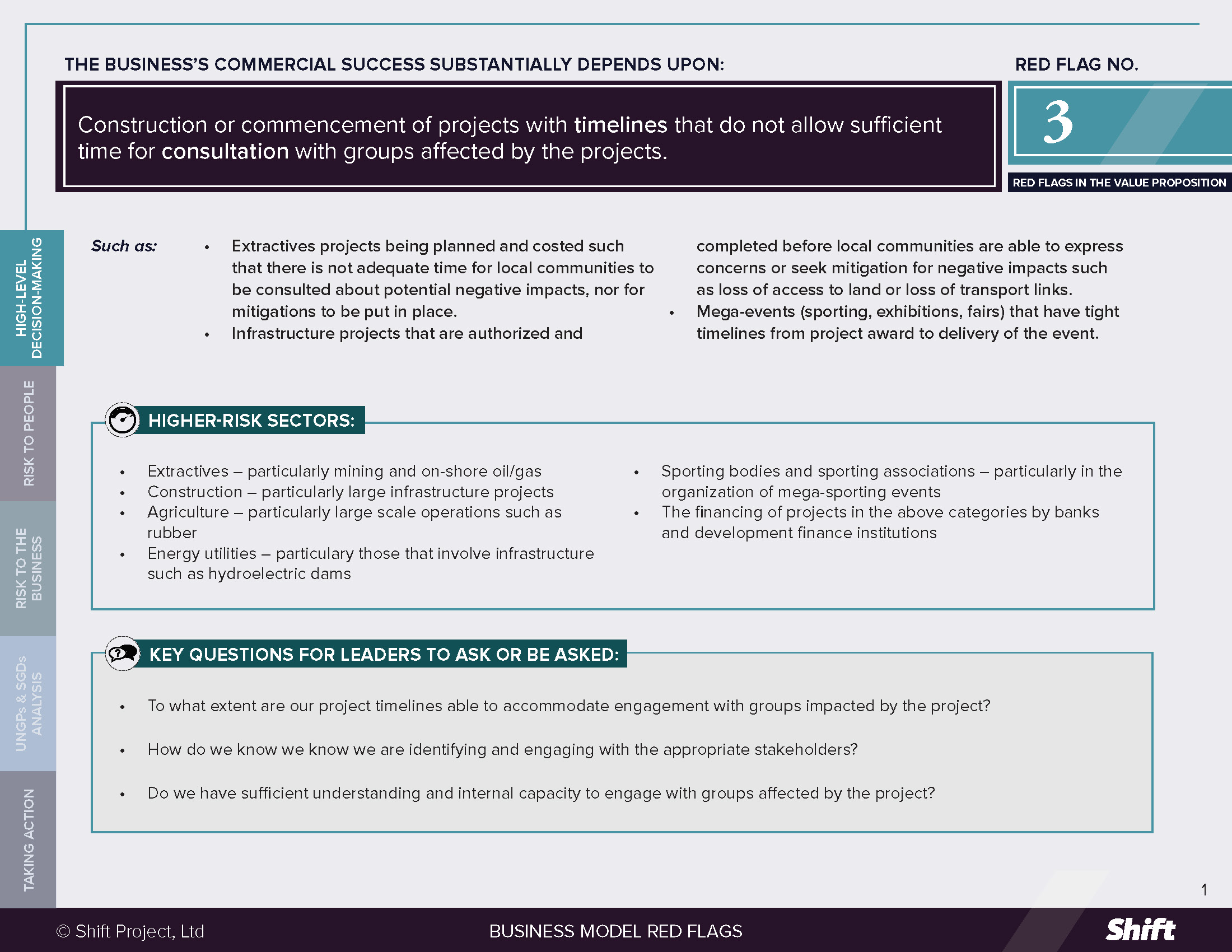

RED FLAG # 3

Construction or commencement of projects with timelines that do not allow sufficient time for consultation with groups affected by the projects.

For Example

- Extractives projects being planned and costed such that there is not adequate time for local communities to be consulted about potential negative impacts, nor for mitigations to be put in place.

- Infrastructure projects that are authorized and completed before local communities are able to express concerns or seek mitigation for negative impacts such as loss of access to land or loss of transport links.

- Mega-events (sporting, exhibitions, fairs) that have tight timelines from project award to delivery of the event.

Higher-Risk Sectors

- Extractives – particularly mining and on-shore oil/gas

- Construction – particularly large infrastructure projects Agriculture – particularly large scale operations such as rubber

- Energy utilities – particulary those that involve infrastructure such as hydroelectric dams

- Sporting bodies and sporting associations – particularly in the organization of mega-sporting events

- The financing of projects in the above categories by banks and development finance institutions

Questions for Leaders

- To what extent are our project timelines able to accommodate engagement with groups impacted by the project?

- How do we know we know we are identifying and engaging with the appropriate stakeholders?

- Do we have sufficient understanding and internal capacity to engage with groups affected by the project?

How to use this resource. ( Click on the “+” sign to expand each section. You can use the side menu to return to the full list of red flags, download this Red Flag as a PDF or share this resource. )

Understanding Risks and Opportunities

Risks to People

Research in the mining sector shows that often there is a tension between “technical time” – the time needed for the construction or completion of a project – and “social time” – the time needed to address community concerns related to the project.

Oftentimes, even when companies see the importance of consulting affected communities; their approaches are not effective.

- A survey of construction project managers shows that while they believe engagement with the local community improves relationships, they see it as a burdensome, arduous, time consuming and costly process.

- A Chatham House report with perspectives from the extractives sector shows that even though setbacks from break-downs in community relations are costly, community engagement often fails because it is seen as a “distraction,” as a box-ticking exercise, or because community relations officers are marginalized or only involved when things go wrong.

- Oxfam’s research shows that while more companies are making commitments to free, prior, informe consent (FPIC), implementation is still weak and gaps remain between policy commitments and practices.

Even companies or financial institutions that have policy commitments to community engagement can sometimes have business models that depend on project timelines which do not allow for sufficient time for consultation with affected stakeholders.This can lead to the following risks to people:

- Loss of Livelihood and Negative Health Impacts: In Mexico, Indigenous communities near a newly built dam in Sonora were not consulted or informed when the dam started to be filled. As the dam was filled, the communities reported they had not yet been relocated, that the dam had flooded areas where they used to access medicinal vegetation and that the project had cut road links to other communities. In Myanmar, opposition to the Myitsone dam on the Irrawaddy river forced the government in 2011 to put the project on hold. The 3.6 billion USD dam was to be financed by China. The dam itself would displace thousands of people and affect fishermen and communities downstream. The reservoir was expected to flood an area the size of Singapore. Local communities reported losing their farmland, which was the source of their income. In addition, the dam would affect cultural rights, as the Myitsone area is believed to be the birthplace of the Kachin people. In recent years, fears that the project may be revived have sparked new protests.

- Forced Displacement: In Brazil, residents of Vila Autódromo resisted displacement to clear land for construction of the Olympic Park in Rio de Janeiro for the 2016 Rio Olympics. Although the majority of the residents had been offered compensation, others preferred not to leave their homes and felt the government’s plans to go ahead with construction amounted to forced eviction. More generally, research shows that in the 20 years to 2007, approximately 2 million people in different countries were displaced by the Olympic Games. Non-sporting mega-events have also led to forced evictions and displacement: for example, 18,000 households were displaced in Shanghai, China, in preparation for the World Expo 2010.

- Access to Water: In the US, the Standing Rock Sioux and other American Indian tribes raised concerns that the Dakota Access Pipeline could damage their water supply and cultural heritage. In 2020, a court ordered a temporary shutdown of the pipeline, finding that the environmental impact assessment had been inadequate. In Peru, local opposition to Newmont’s Conga mine forced the company in 2016 to remove the 4.8 bilion USD project from its pipeline. The project had been approved by the national government despite 78% of people in the province of Cajamarca were opposed to it. Local communities challenged the environmental impact of the project: it would cause the loss of four mountain lakes and damage five river basins on which the lives of local comminuties depend. This would not only impact the health and livelihoods of local communities, but also the culture and tradition of campesino communities (traditional farming communities).

- Environmental Damage: The lack of consultation in the construction of a tourist train in Yucatán, Mexico raised concerns that the new towns that will be created along the line will put pressure on biodiversity and nature reserves which are managed by local communities.

- Loss of Cultural Heritage: In Australia, the Wangan and Jagalingou community challenged the provision by Siemens of rail signaling to the Adani coalmine, stating that they had not provided approval for the project and the mine would cause environmental damage and limit their access to ancestral ceremonial grounds. In Cambodia, communities from Ratanakiri province filed complaints with the Compliance Advisory Ombudsman (CAO) of the International Finance Corporation (IFC) related to the IFC’s investment in Vietnamese rubber company Hoang Anh Gia Lai (HAGL). Besides IFC, other financial institutions that invested in HAGL included Deutsche Bank, Credit Suisse and Dragon Capital Group. Local communites complained that HAGL’s use of its rubber land concessions had resulted in loss of forest and grazing land, destruction of burial grounds, and lack of access to resin trees and non-timber forest products necessariy to sustain livelihoods. Moreover, communites reported that no effort was made by HAGL to obtained their free, prior informed consent, involve affected communities in the decision-making process, or provide adequate information to them. The CAO facilitated a dispute resolution process, which resulted in HAGL agreeing to a number of remedial measures. However, the company later unilaterally witdrew from the process. As of 2020, the case is still ongoing.

- Violation of Indigenous Peoples Rights: It is important to highlight Indigenous peoples as a vulnerable group among affected stakeholders. Failure to obtain FPIC can undermine Indigenous peoples’ right to self-determination. It can also undermine their access to other Indigenous peoples’ rights such as life, liberty, security, culture, language, spirituality, education, information, employment, etc. In some contexts, Indigenous leaders play the role of human rights defenders; they are therefore at risk of persecution from state or non-state actors. In Guatemala, UN human rights experts including the Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, raised concerns about the imprisonment of an Indigenous leader for campaigning against a hydroelectric project. The Oxec hydroelectric dam project had started without the consent of the affected communities.

Guatemala’s Supreme Court suspended the project and then the Constitutional Court recognized the right to free, prior, informed consent of the q’eechí’ peoples. However, in 2018, Indigenous leader Bernardo Caal Xól was sentenced to seven years and four months’ imprisonment on charges brought by representatives of the hydroelectric company.

Risks to the Business

Business models that substantially depend on project timelines which do not allow for sufficient time for consultation with affected stakeholders can lead to the following risks to companies:

- Reputational Damage: Public backlash has forced cities that intended to host mega-sporting events to withdraw from the process (Boston) or scale-down their amibitions (Tokyo).

- Financial Risks: The shutdown of the US Dakota Access pipeline is estimated to cost $643 million in 2020 and $1.4 billion in 2021. Representatives from the extractives sector reported that delayed production in a major mining project due can cost $20 million per week.

- Operational Risks Linked to Social Unrest: From the riots related to the Rio 2016 summer Olympics to the deaths of demonstrators protesting the Conga Mine in Peru, social unrest can create operational risks for the company as well as security risks for company staff and local communities.

- Legal Risks: Companies operating in contexts where the local government does not follow international standards on Free, Prior, Informed Consent (FPIC) risk facing legal action locally or internationally. For instance, civil society organizations in Guatemala challenged the government before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) for failing to consult local communities in line with International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention 169 regarding the authorization of the Marlin Mine.

What the UN Guiding Principles say

*For an explanation of how companies can be involved in human rightsimpacts, and their related responsibilities, see here.

- Companies can cause adverse human rights impacts when they fail to carry out meaningful consultation with affected stakeholders and their actions negatively affect human rights. A failure to allow time for the conduct of Free, Prior and Informed Consultation (FPIC) with affected Indigenous communities, or to ensure that FPIC with these communities has been conducted by others, is itself a breach of Indigenous people’s human rights. More generally, a company may cause human rights impacts when it sets timescales which preclude consultation with affected communities as part of a risk assessment and mitigation process, and the company’s actions then have negative impacts on communities such as forced displacement, depriving communities of access to water, food or livelihoods or preventing them of entering cultural sites.

- Organizations (including companies, mega-event organizers and financial institutions) can contribute to adverse human rights impacts when their business models create demand for speed in the delivery of projects by third parties, and the demand for speed prevents third parties from carrying out meaningful consultation with local communities, resulting in adverse human rights impacts.

Possible Contributions to the SDGs

Addressing impacts on people associated with this red flag can contribute to ensuring responsible, inclusive and participatory and representative decision-making at all levels (Target 16.7 of SDG 16: promoting peaceful and inclusive societies). The results of consultation with groups affected by projects can enable companies to better understand and mitigate risks to people, which can contribute to the following SDGs:

SDG 1: End poverty in all its forms everywhere.

Adequate consultation can help ensure that people – particularly vulnerable communities – have equal rights to economic resources, including ownership and control over land.

SDG 2: Zero hunger.

Adequate consultation can help agricultural productivity and incomes of small-scale farmers, in particular women and Indigenous communities, including through secure and equal access to land and productive resources.

SDG 3: Good health and wellbeing.

Adequate consultation can help protect stakeholders’ health by preventing negative impacts such as pollution of soil, air or water sources, or impacts from poor working conditions such as fatigue, stress and accidents.

SDG 6: Clean water and sanitation.

Adequate consultation can help prevent pollution of water sources.

Taking Action

Due Diligence Lines of Inquiry

- Do we understand the local context and the potential ways in which our project can impact on people?

- Do we have a mechanism to sensitize our staff about local issues and the local context?

- Do we know which stakeholders we need to consult and how to structure the consultations to make them meaningful and accessible?

- Do our project plans allow sufficient time for the consultation to take place?

- Do we actively support the role of community relations managers to carry out the consultations?

- Are we prepared to act on the advice of community relations managers? Are we prepared to review the project plan based on insights from the consultations?

- Do we measure the cost of conflict with local communities?

Mitigation Examples

*Mitigation examples are current or historical examples for reference, but do not offer insight into their relative maturity or effectiveness.

- Encouraging active citizenship by building the capacity of civil society to unlock productive dialogue between the company and local communities. For example, Oxfam’s NORAD project in Ghana, Tanzania and Mozambique to improve petroleum governance.

- Dialogue tables co-owned by companies, local communities and stakeholders (civil society) as spaces for respectful, patient engagement and joint problem-solving. The dialogue tables can be facilitated by neutral third parties, which can help companies and communities build trust in the process. For instance, Anglo American participated in dialogue tables in the Quellaveco project in Peru. This enabled the company to make commitments to the local community on water management, environmental protection and social investment.

- Monitoring agencies set up between representatives of Indigenous peoples, local government and businesses to enable joint decision-making and monitoring compliance with the terms of the agreement between the company and local communities. The Snap Lake Environmental Monitoring Agency was set up by DeBeers, the Government of the Northwest Territories of Canada and a number of aboriginal groups. Its board was comprised of representatives of Indigenous groups, and the agency functioned as a “watchdog” to monitor environmental compliance by DeBeers.

- Tailored approaches that respond to community concerns and go beyond compliance can help companies and communities build trust. In New Zealand, Newmont Waihi Gold (NWG) wanted to expand their gold mining beneath homes of the local community. The company realized that a primary concern of the community related to property damage. In response, NWG set up a number of platforms that went beyond the legal requirements to provide transparency and enable the community a role in decision-making. These included an independent ombudsman for property matters, a policy to guide how the company would respond to matters of property damage, and a community forum with members of the community, the company and local government.

- Empowered community liaison officers who, in addition to being approachable and personable towards the local community, can take decisive action when concerns are raised. For instance, at Newmont Waihi Gold (NWG) in New Zealand, the community liaison officer had the power to stop operations when the community raised certain issues, even if the pit was operating within consent limits.

Other Tools and Resources

General:

Sector Specific Examples:

- IIED paper (2016) Meaningful community engagement in the extractives sector.

- IPIECA (2018) Free Prior Informed Consent (FPIC) toolkit, IPIECA

Business Model Red Flags

Business Model Red Flags  Tool for Indicator Design

Tool for Indicator Design