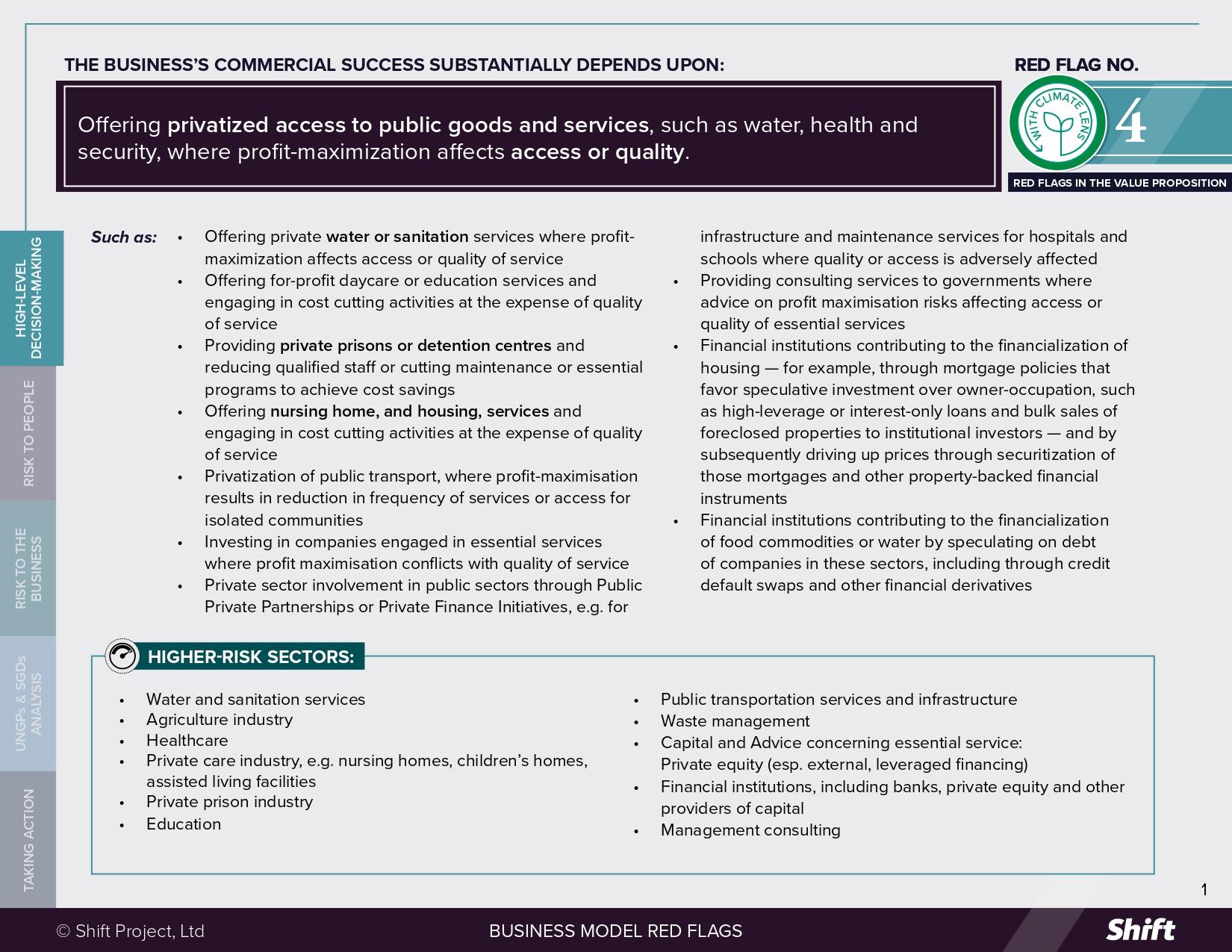

RED FLAG # 4

The business’s commercial success substantially depends upon offering privatized access to public goods and services, such as water, health, security and housing, where profit-maximization affects

access or quality

For Example

- Offering private water or sanitation services where profit-maximization affects access or quality of service

- Offering nursing home services and engaging in cost-cutting activities at the expense of quality of service

- Offering for-profit daycare or education services and engaging in cost cutting activities at the expense of quality of service

- Providing private prisons or detention centres and reducing qualified staff or cutting maintenance or essential programs to achieve cost savings

- Privatization of public transport, where profit-maximisation results in reduction in frequency of services or access for isolated communities

- Investing in companies engaged in essential services where profit maximisation conflicts with quality of service

- Private sector involvement in public sectors through Public Private Partnerships or Private Finance Initiatives, e.g. for infrastructure and maintenance services for hospitals and schools where quality or access is adversely affected

- Providing consulting services to governments where advice on profit maximisation risks affecting access or quality of essential services

- Financial institutions contributing to the financialization of housing — for example, through mortgage policies that favor speculative investment over owner-occupation, such as high-leverage or interest-only loans and bulk sales of foreclosed properties to institutional investors — and by subsequently driving up prices through securitization of those mortgages and other property-backed financial instruments.

- Financial institutions contributing to the financialization of food commodities or water by speculating on debt of companies in these sectors, including through credit default swaps and other financial derivatives

Higher-Risk Sectors

- Water and sanitation services

- Agriculture industry

- Healthcare

- Care industry, e.g. nursing homes, children’s homes, assisted living facilities

- Private prison industry

- Education

- Public transportation services and infrastructure

- Waste management

- Capital and Advice concerning essential service:

- Private equity (esp. external, leveraged financing)

- Financial institutions, including banks, private equity and other providers of capital

- Management consulting

Questions for leaders

- How does the company identify and respond to any tensions between its responsibility to ensure access and quality, on the one hand, and the need to deliver financial results on the other? What policies guide decision-making?

- How does the company ensure that its lobbying positions (for example, on regulation relating to access or quality) do not have a potential impact on human rights?

- What systems does the company have in place to ensure that early warnings with regard to issues of access or quality of service make their way to senior decision makers?

- How does the company ensure access to remedies for people denied adequate access or quality of service?

- Are there any inherent perverse incentives in the company’s business model, whereby the denial or reduction of service automatically reduces costs and/or increases revenues without jeopardizing customer retention — for example, by limiting access to high-cost services, deferring maintenance or upgrades, shortening service hours, or prioritizing profitable customer segments over those with greater need?

How to use this resource. ( Click on the “+” sign to expand each section. You can use the side menu to return to the full list of red flags, download this Red Flag as a PDF or share this resource. )

Understanding Risks and Opportunities

Risks to People

|

Risks to the Business

-

Financial and Legal Risks, including Loss of Investment:

-

Water: In 2014 a water crisis occurred in Flint, Michigan, where the water utility was managed by Veolia, a French multinational. The crisis exposed residents to high levels of lead, which is a neurotoxin and “a decade later, community members continue to grapple with the long term physical and mental health problems unleashed by the water crisis”. According to reports, Veolia knew about issues related to lead in the water, but at the time it was “interested in securing future work with Flint”, so did not take appropriate action. After several years of litigation involving multiple defendants, including the State of Michigan and Veolia North America, there have been several financial settlements for impacted Flint residents, amounting to an estimated USD660 million, as of October 2024. In March 2025 in the United Kingdom, water company Thames Water narrowly avoided temporary nationalization; 30 years of privatization, including issues associated with the involvement of financial institutions, are said to have led to accelerated costs of borrowing and higher costs to consumers.

-

Security: Investors in a company to which the Australian government outsourced the operation of offshore detention facilities for asylum seekers, came under pressure from civil society to divest due to allegations of inhumane conditions at the camps. A sustained campaign by faith-based investors and investment networks from 2017 to 2019 focused on investment in the private prison industry. The investors “raised questions about human rights abuses in the companies’ prisons that were uncovered by investigations and identified in lawsuits”, and cited “inmate deaths, poor medical care, allegations of physical and sexual abuse of detainees, and violence.” JPMorgan Chase announced in March 2019 that it “will no longer bank the private prison industry.” In 2021 a US prison snacks provider faced investor pushback on a debt deal, with one investor noting that “[a]ny business whose model is a beneficiary of increased levels of incarceration is really being met with a number of institutions that are outright prohibiting participation” and noting that this “limits the potential buyer base.” A “prolific private equity investor in prisons” also faced criticism along with the prison companies themselves for business models that “very clearly prey on communities of color” by effectively turning systemic racial inequalities into a source of revenue.

-

Housing: There has been considerable public concern about financialization of housing. In Ireland in 2021, almost 40,000 people signed a petition to demand the Government take more action against “vulture” investment funds purchasing large quantities of (distressed or undervalued) residential real estate. Several U.S. Senators have publicly addressed concerns about Blackstone’s role in the housing market, including a 2022 letter urging the firm to halt evictions and criticizing its impact on rental affordability.

-

-

Reputational, financial and legal risks:

-

Privatized essential service providers have heightened exposure to bribery and corruption risks, particularly in the context of high-value, large-scale contracts and complex procurement processes. This is exacerbated in regions with weak oversight and regulatory frameworks. Transparency International highlights that the water sector, in particular, is characterized by high-risk procurement, with various forms of bribery related to licensing, procurement, and construction. Moreover, the Water Integrity Network reports that corruption can increase the costs of building water infrastructure by as much as 40%, equating to an additional $12 billion annually needed to provide worldwide safe drinking water and sanitation.

-

In 2018, the US Department of Education deemed a number of private-equity owned for-profit colleges “not financially responsible.”

-

-

Business Opportunity and Continuity Risks: Risk of loss of government contracts, increased scrutiny and reconsideration of the social license to operate of the entire industry, potentially leading to government intervention, including renationalization or “remunicipalization” of services.

-

Following the G4S immigration center scandal mentioned above, the Independent newspaper ran an article by the paper’s Chief Business Commentator with the headline “Private companies should not be doing this sort of work.” The company later announced it would end its involvement in the immigration and asylum sector but remain involved in the private prison sector.

-

In 2016 following mounting criticism on conditions, the US Justice Department ended its use of private prisons. Civil society noted that the move “should prompt other federal departments and state governments” to follow suit (see Human Rights Watch).

-

In 2017 the Australian government closed its main offshore immigration detention processing center on Manus Island following allegations of inhumane conditions at the center, operated by a private company.

-

A “significant global trend” has been observed involving the “rejection of the private sector, due to its failures to provide adequate services” in water and sanitation, leading to renewed public ownership of those services (see UN Special Rapporteur for Special Rapporteur on the human rights to water and sanitation). Civil society has produced guides for remunicipalization of water for communities and policy makers, premised on claims that “PPPs turn out to be worse for public budgets in the long term, and lead to poor services and a loss of democratic transparency.” In the UK, there have been calls to “abandon the notion that public transport can be left to the private market” from the perspective of quality and accessibility of services.

-

Following years of concern about safety, accountability, financial oversight, and fragmented operations in the context of privatized rail infrastructure, the UK has been phasing out passenger rail franchising, with services being brought into public ownership under the Passenger Railway Services (Public Ownership) Act 2024. The process is expected to be completed by late 2027.

-

In 2015, a Swedish council became the first to limit private profits in healthcare (specifically capping private profits in publicly funded healthcare at a regional level).

-

What the UN Guiding Principles Say

The UNGPs address privatization directly in Principle 5 and its commentary, noting that “States do not relinquish their international human rights law obligations when they privatize the delivery of services that may impact upon the enjoyment of human rights”. As such in the context of privatization, both the state duty to protect, and the corporate responsibility to respect, human rights are directly relevant to these types of impact.

If they fail to meet basic standards for enjoyment of rights, companies offering services upon which dependent populations rely to realize their rights, are at risk of causing a human rights impact.

The following situations are examples of situations that may give rise to an argument of contributing to impacts:

-

A private company reduces services to a level that creates an environment in which violence flourishes (e.g. in a private prison);

-

Aggressive pricing by the company is a factor in rendering the final price of a good or service too high for vulnerable or isolated populations to access it.

Possible Contributions to the SDGs

|

Providing products and services in the sectors addressed in this red flag can contribute a range of SDGs, including:

|

Taking Action

Due Diligence Lines of Inquiry

Example in focus: Nursing Care Facilities

Example in focus: Investment in Housing (From SHARE)

|

Mitigation Examples

* Mitigation examples are current or historical examples for reference, but do not offer insight into their relative maturity or effectiveness.

-

In Senegal, private company Senegalaise des Eaux (SDE), a subsidiary of Saur International, has been the private partner in a public-private partnership for water management since 1996. Water supply and sanitation in Senegal is characterized by a relatively high level of access compared to the average of Sub-Saharan Africa. The company extended the service to reach low-income settlements, with social tariffs available to ensure affordability, and offers detailed customer surveys and a complaints system (see C. de Albuquerque)

-

Other mitigation examples have involved action on the part of the state to maintain or reclaim control over aspects of the service provision that intersects with respect for stakeholders’ rights.

-

For example, following accusations of abuse of detainees, the BBC reported that the UK Home Office had concluded that contracts for the private provision of services in migrant detention centers were “no longer fit for purpose, given the lack of scope to impose financial penalties and enforce improvements in conditions and treatment” and that it had plans to include in new contracts “performance measures covering staff recruitment, induction, training, mentoring and culture” and “a contractual role for the Home Office to monitor the appropriateness of the use of force against detainees and the care of staff and detainees following an incident”.

-

In the nursing care space, US researchers have called for “policy changes that better align private equity incentives with the interests of consumers, or patients” such as by “linking provider payments to performance, which could include metrics like quality and efficiency”.

-

Alternate Models

-

Private Equity

-

New models of purpose-driven private equity firms state their goals to provide conscious capital driven by their values and the interests of stakeholders; see e.g. Spindletop Capital which aims to provide “purpose-driven healthcare growth equity”; Leapfrog Investments which states that it focuses on “providing critical health services to underserved consumers” in Africa and Asia, and ABC Impact with the stated aim of “provid[ing] growth equity to purposeful companies driving meaningful change in line with the UN Sustainable Development Goals” including in the fields of water solutions and healthcare and education, and measuring outcomes through an impact measurement model.

-

A 2018 legal proposition in Sweden to cap returns on invested capital in publicly funded services to 7% was directly related to concerns about private equity involvement in sectors like nursing homes and schools. Ultimately unsuccessful, the initiative aimed to limit excessive profits and ensure more funds were reinvested into improving service quality.

-

-

The Global Alliance for Banking on Values provides an overview of how values-based banks are working with affordable housing providers, “from developers to social organizations or public institutions, for reasons that range from viewing housing as a fundamental right, creating environment friendly and sustainable communities, or protecting disadvantaged communities such as migrants and individuals and families living on low incomes”. For example, GABV notes that in Germany, Umweltbank has financed the “City quartier Güterbahnhof” in the city of Tübingen wherein 93 out of the 157 flats are categorized as social housing.

Other Tools and Resources

General

-

University of Leeds paper (2018) discusses privatization and the exacerbation of inequality in the context of a various once-public services (e.g. water, electricity, transportation): Privatization, Inequality and Poverty in the UK: Briefing prepared for UN Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights

-

The OECD’s Infrastructure Anti-Corruption Toolbox (I ACT) is a holistic multi-stakeholder approach to empowering actors across the infrastructure value chain to prevent, detect and report corruption.

-

DIHR’s AAAQ (Availability, Accessibility, Acceptability and Quality) toolbox aims to support the operationalization of the rights to water, sanitation, food, housing, health, and education. Designed with a multi-stakeholder approach in mind, the open-source Toolbox offers common methodologies for all stakeholders as well as tailored tools for states, rights-holders, business, civil society and National Human Rights Institutions (NHRIs).

Private water and sanitation services:

-

The Special Rapporteur on the human rights to water and sanitation will focus his 2020 report on “privatization and the human rights to water and sanitation.” See concept note and progress of public consultations here.

-

Shift, Pacific Institute and UN Global Compact (2015) Guidance for Companies on Respecting the Human Rights to Water and Sanitation: Bringing a Human Rights Lens to Corporate Water Stewardship.

Private Prisons/ Detention Centers:

-

Human Rights Advocates submission on Article 9 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights discusses the effect of the profit motive on conditions in private prisons as a part of its “focus on what governments are required to do to avoid having detention becoming arbitrary when a person’s liberty is turned over to a private entity.”

-

Human Rights Watch (2017) Code Red: The Fatal Consequences of Dangerously Substandard Medical Care in Immigration Detention a report analyzing 15 deaths in immigration detention custody in the US, concluding that “healthcare and oversight failures … present in so many of them” point to “larger, systemic deficits in immigration detention facility health care” in both publicly and privately run facilities.

Residential Care Facilities

-

Human Rights Watch (2018) “They Want Docile”: How Nursing Homes in the United States Overmedicate People with Dementia.

-

See also below under Private Equity

Private Equity

-

Principles for Responsible Investment (2020) “Aligning private equity investment practices and structures with ESG goals”

-

Knowledge at Wharton (2024) “How to Align Private Equity Motives with Nursing Home Outcomes”

-

Bernaz, (2023) “Business Strategy as Human Rights Risk: The Case of Private Equity”: This article (which cites Shift’s Business Model Red Flags) applies business and human rights principles to private equity business strategy and concludes that “the underlying model makes these harms inevitable, and therefore […] the PE model itself should be considered a human rights risk”.

-

The Predistribution Initiative: “[PDI] is a nonpartisan, multistakeholder non-profit that works with investors and their stakeholders to improve financial analysis and investment decision-making processes in ways that more adequately value workers, communities and nature”.

Financialization of Housing

-

Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, Special Rapporteur (SR) on the Right to Adequate Housing. Financialization of Housing. This portal includes reports from the SR, including country-specific reports, resources including a documentary, and a response from Blackstone to a letter on the subject from the SR.

-

Responsible Investment Organisation SHARE has a portal on affordable housing, and Principles and Progressive Framework for Responsible Investment in Housing

Citation of research papers and other resources does not constitute an endorsement by Shift of their conclusions.

Business Model Red Flags

Business Model Red Flags  Tool for Indicator Design

Tool for Indicator Design