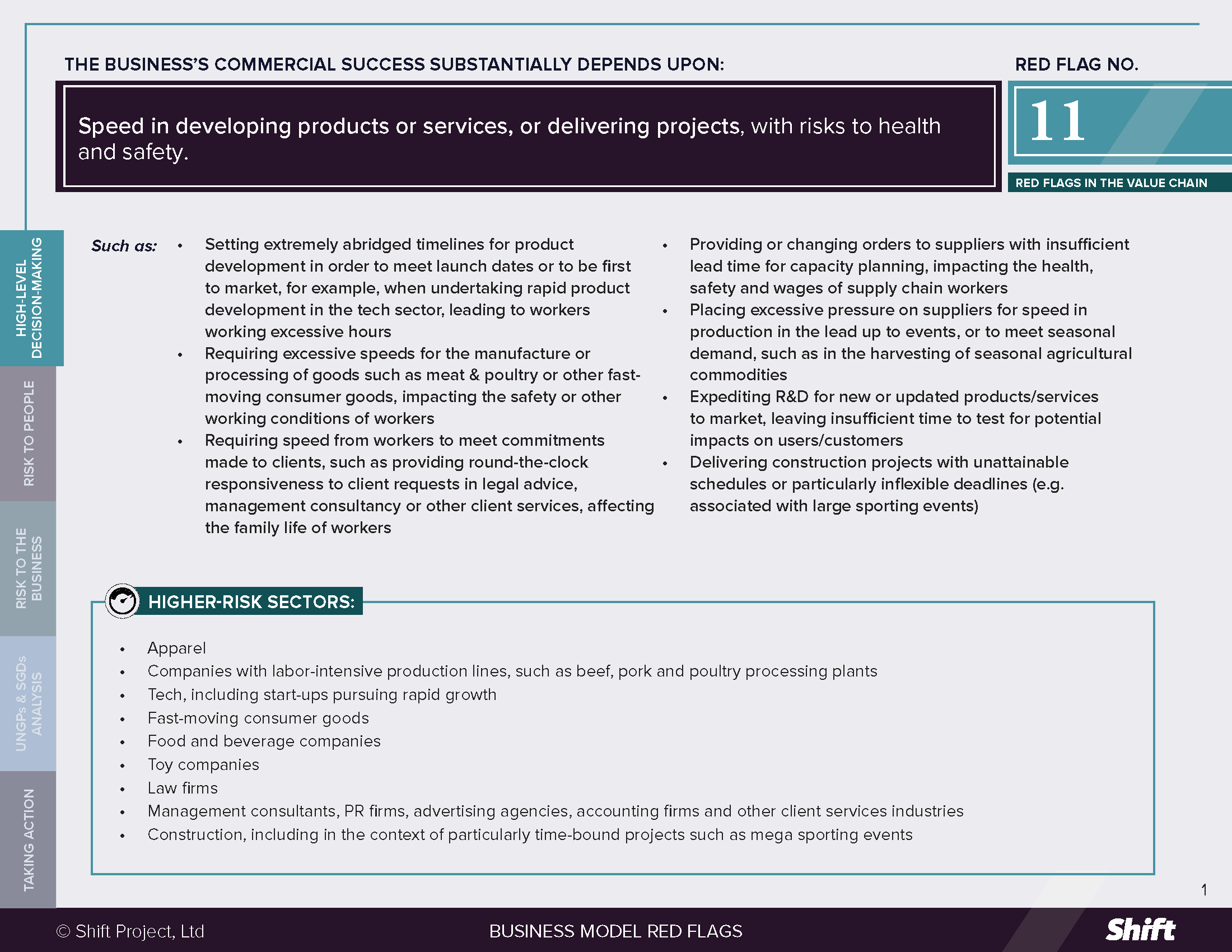

RED FLAG # 11

Speed in developing products or services, or delivering projects, with risks to health and safety.

For Example

- Setting extremely abridged timelines for product development in order to meet launch dates or to be first to market, for example, when undertaking rapid product development in the tech sector, leading to workers working excessive hours

- Requiring excessive speeds for the manufacture or processing of goods such as meat & poultry or other fast- moving consumer goods, impacting the safety or other working conditions of workers

- Requiring speed from workers to meet commitments made to clients, such as providing round-the-clock responsiveness to client requests in legal advice, management consultancy or other client services, affecting the family life of workers

- Providing or changing orders to suppliers with insufficient lead time for capacity planning, impacting the health, safety and wages of supply chain workers

- Placing excessive pressure on suppliers for speed in production in the lead up to events, or to meet seasonal demand, such as in the harvesting of seasonal agricultural commodities

- Expediting R&D for new or updated products/services to market, leaving insufficient time to test for potential impacts on users/customers

- Delivering construction projects with unattainable schedules or particularly inflexible deadlines (e.g. associated with large sporting events)

Higher-Risk Sectors

- Apparel

- Companies with labor-intensive production lines, such as beef, pork and poultry processing plants

- Tech, including start-ups pursuing rapid growth

- Fast-moving consumer goods

- Food and beverage companies

- Toy companies

- Law firms

- Management consultants, PR firms, advertising agencies, accounting firms and other client services industries

- Construction, including in the context of particularly time-bound projects such as mega sporting events

Questions For Leaders

- How does the company understand whether and to what extent the incorporation of speed in the value proposition impacts the human rights of workers, suppliers or other business partners?

- How does the company ensure that demands for speed in the R&D process leave sufficient time for considering and mitigating potential unintended impacts on customers/end users?

How to use this resource. ( Click on the “+” sign to expand each section. You can use the side menu to return to the full list of red flags, download this Red Flag as a PDF or share this resource. )

Understanding Risks and Opportunities

Risks to People

Speed is a key element of the value proposition and value chain in many business models. For some, speed is “the most important thing for [a] business”; it is “everything in business.” Speed in product innovation, speed to market, speed in delivery, speed in the preparation of targeted marketing campaigns that react to cultural events: the importance of speed as a competitive advantage is said to be increasing, with commentators stating that “with the pace at which society progresses, companies have to do whatever it takes to stay relevant.”

Demands for speed in the business model become problematic from a rights perspective when they are absorbed in ways that place undue pressure on vulnerable people in the company’s operations and value chain. Demands for speed can have effects across the value chain, often on the most vulnerable people – such as young workers; factory workers, including migrant workers and women workers; and small-holder farmers. Some examples of impacts are below, with impacts on workers’ right to health, right to just and favorable conditions of work (including rest, leisure and adequate limitation of working hours), right to a family life, and in some cases where excessive hours are demanded, right to fair wages or right to a living wage for hours worked.

- Client Services Firms may promise delivery of services to clients in ways that place undue pressure on workers, often at a junior level in the organization, leading to excessive hours and/or round-the-clock availability with resulting risks to physical and mental health. This is exacerbated when factors such as the high price of services and/or representations by partners in the firm to clients, create an understanding that the firm will respond to client demands immediately at all hours.

- Tech Companies for which providing the “latest” updates or functionality is a key part of the value proposition, or tech start- ups with a “grow fast or die” mindset, pursuing “hockey-stick growth”, can “burn through employees” as workers become mentally or physically unable to maintain the work-levels expected.

- For production line jobs, intense pressure to keep up with production can risk injury and disabling illness.

- In 2019 Human Rights Watch reported high rates of serious injury and chronic illness among workers at chicken, hog, and cattle slaughtering and processing plants; interviews with workers found that “nearly all the interviewed workers identified production speed as the factor that made their job dangerous.” Advocacy organizations in the US have expressed concern about risks increasing as the “government has also proposed regulations that would bring in new inspection systems and eliminate caps on slaughter line speeds.”

- For apparel companies or FMCG companies speed of product innovation and delivery may be a key element of the value proposition and be reflected in purchasing practices. If not addressed through effective mitigation measures, this can adversely impact the health, safety and/or income of workers at various tiers of the supply chain as the pressure ripples throughout the value chain. For example:

- Supply chain factories given short lead times can feel obliged to require workers to work unreasonable hours, or to discriminate against pregnant workers on the basis that they cannot meet such demands. (See also Red Flag 1).

- Logistics providers can work to unreasonable deadlines or schedules. (See also Red Flag 2).

- Farmers or others working at the level of cultivating raw materials can face sudden and unmeetable demands for increased supply.

- Factories producing seasonal products, such as Christmas toys, can require excessive overtime of workers.

- In the construction industry, schedule pressure and deadlines can erode safety and promote risk-taking. One of the many contexts in which this can be observed is the “extreme pressure that often characterises the construction phase prior to mega sporting events.” For example, in 2016 the Guardian reported that the Chief Inspector of Labor Conditions for the 2016 Rio Olympic Games had criticized the organizers of the Rio Olympics at a memorial service for 11 workers killed on construction projects, stating that “rushed construction caused by delays and poor planning was the primary factor in the high number of fatalities on Games-related infrastructure projects.”

Risks to the business

- Financial and Business Continuity Risks:

- Where taken to the extreme, speed of roll-outs has been noted as a factor in “tech product launch fail[ures].”

- Where workers reach the limits of their capacity to absorb demands for greater speed, continued demands risk injuring and/or alienating the workforce. Employees may resist through the only means available where appropriate avenues to discuss the impacts of speed are unavailable: in the poultry processing industry, following injuries and unmet requests from workers to slow line speeds, “workers began jamming chicken bones into the machinery to stop the processing line. It was the only way they could get some relief from the frantic pace.” (See Southern Poverty Law Centre).

- Operational and Reputational Risks: Where excessive speed is built into the business model, it can undermine sustainability efforts at the operational level. Moreover, increasingly savvy consumers, advocacy organizations and investors are looking beyond individual sustainability initiatives and programs and are quick to label them “greenwashing” if they perceive that the business model continues to increase risk of negative impacts.

- Reputational Risks: The prefix “fast” has developed negative connotations when associated with products (and industries producing such products) due to concerns about both environmental impacts and impacts on supply chain workers, as well as community and worker health.

What the UN guiding principles say

*For an explanation of how companies can be involved in human rights impacts, and their related responsibilities, see here.

Where a company demands excessive speed from its workers, it may cause impacts on their health, safety or other working conditions. The company may also cause impacts if products are unsafe due to excessive speed in R&D phases.

Where a company’s purchasing practices create demands for speed in the supply chain, they may contribute to impacts caused by suppliers at different tiers in their chain, in their efforts to comply with these demands.

Possible contributions to the SDGs

Addressing impacts to people associated with this red flag can contribute to, inter alia:

SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth, in particular Target 8.8 on protecting, “labor rights and promot[ing] safe and secure working environments for all workers, including migrant workers, in particular women migrants, and those in precarious employment.” Engagement with the human dimensions of “fast” business models can have positive environmental impacts, and contribute to Target 8.4, “Improve progressively, through 2030, global resource efficiency in consumption and production and endeavour to decouple economic growth from environmental degradation, in accordance with the 10- year framework of programmes on sustainable consumption and production, with developed countries taking the lead.”

Taking Action

Due Diligence lines of Inquiry

- Can we map where demands for speed are originating – both internally and externally to our business?

- How are demands for speed absorbed within our value chain and by whom? How do we know whether or to what extent those pressures are passed onto vulnerable workers in our value chain?

- How do we attempt to avoid or reduce such impacts and how do we know whether we are succeeding?

- What channels do we have for hearing concerns from our own workers, and workers in our value chain, related to any impacts from demands for speed, and to hear their views on how we could reduce these impacts? How do we know whether people feel able to use them?

- Do we involve internal human rights experts at the R&D stage to help identify potential risks to people from rapid product roll-outs and adaptations?

Mitigation Examples

*Mitigation examples are current or historical examples for reference, but do not offer insight into their relative maturity or effectiveness.

Speed in the Supply Chain

- Buyer strategies to mitigate the demand for speed include joint capacity planning: “Kellogg undertakes a “joint business planning process” with its key suppliers that includes the evaluation of its responsible sourcing practices. Issues such as “… lead-time expectations [and] production schedule changes… are discussed with suppliers.” (From Know the Chain).

- Primark seeks to mitigate the impact of fast fashion by “selling a lot of the same items” rather than responding to changing fashion demands, and this allows them to “plac[e] large orders with the factories and suppliers.” Primark focuses on uses “off-season factory time for production [which] lengthens the lead time and helps a factory to plan their production more effectively and provides stable employment in typical low seasons.” This model may assist suppliers to manage fluctuating demand, including demands for speed from other buyers.

Speed in Meeting Deadlines for Construction

- In the construction context, researchers studying strategies to counter the effects of schedule pressure highlight the importance of, for example, attainable schedules, proactive planning and extensive communication with workers. Simulation models have highlighted two critical success factors for safety management in construction operations: managing rework and schedule delays. See further here.

Alternative Models

- In the tech world, some have called for alternative business models, particularly for start-ups, that reframe success as long-term or organic growth.

- In apparel and FMCG, various “slow” movements have recognized the social and environmental advantages of reducing the speed imperative from the business model.

- The “slow food” movement encourages the consumption of organically grown regional produce at accessible prices for consumers and fair conditions and pay for producers.

- The “slow goods” movement applies slow movement principles to the concept, design and manufacturing of physical objects. It focuses on “low production runs, the usage of craftspeople within the process and on-shore manufacturing. Proponents of this philosophy seek and collaborate with smaller, local supply and service partners.” (Wikipedia).

- Slow Fashion: Slow and Steady Wins the Race is a US clothing collection that creates classic garments and accessories made using simple, durable materials. The company introduces new styles at a regulated pace year-round, rather than the usual accelerated pace of the seasonal fashion schedule.

-

- Various other examples, including Patagonia and Boden, are detailed in the article “35 Ethical & Sustainable Clothing Brands Betting Against Fast Fashion” here.

Other tools and Resources

On Production Lines

- Human Rights Watch (2019) When We’re Dead and Buried, Our Bones Will Keep Hurting: Workers’ Rights Under Threat in US Meat and Poultry Plants.

- South Poverty Law Centre (2013) Unsafe at These Speeds.

On Technology-based Start-ups

- Medium, Stanier (2019) Silicon Valley’s Grow-or-Die Culture Is Costing Us: Startup founders must set a new tone instead of burning through their employees.

On Construction

- Industrial Safety and Hygiene News, Leemann (2016) Deadlines can erode safety and promote risk-taking: Summarizes studies on the identification and mitigation of impacts from demands for speed in construction.

Business Model Red Flags

Business Model Red Flags  Tool for Indicator Design

Tool for Indicator Design