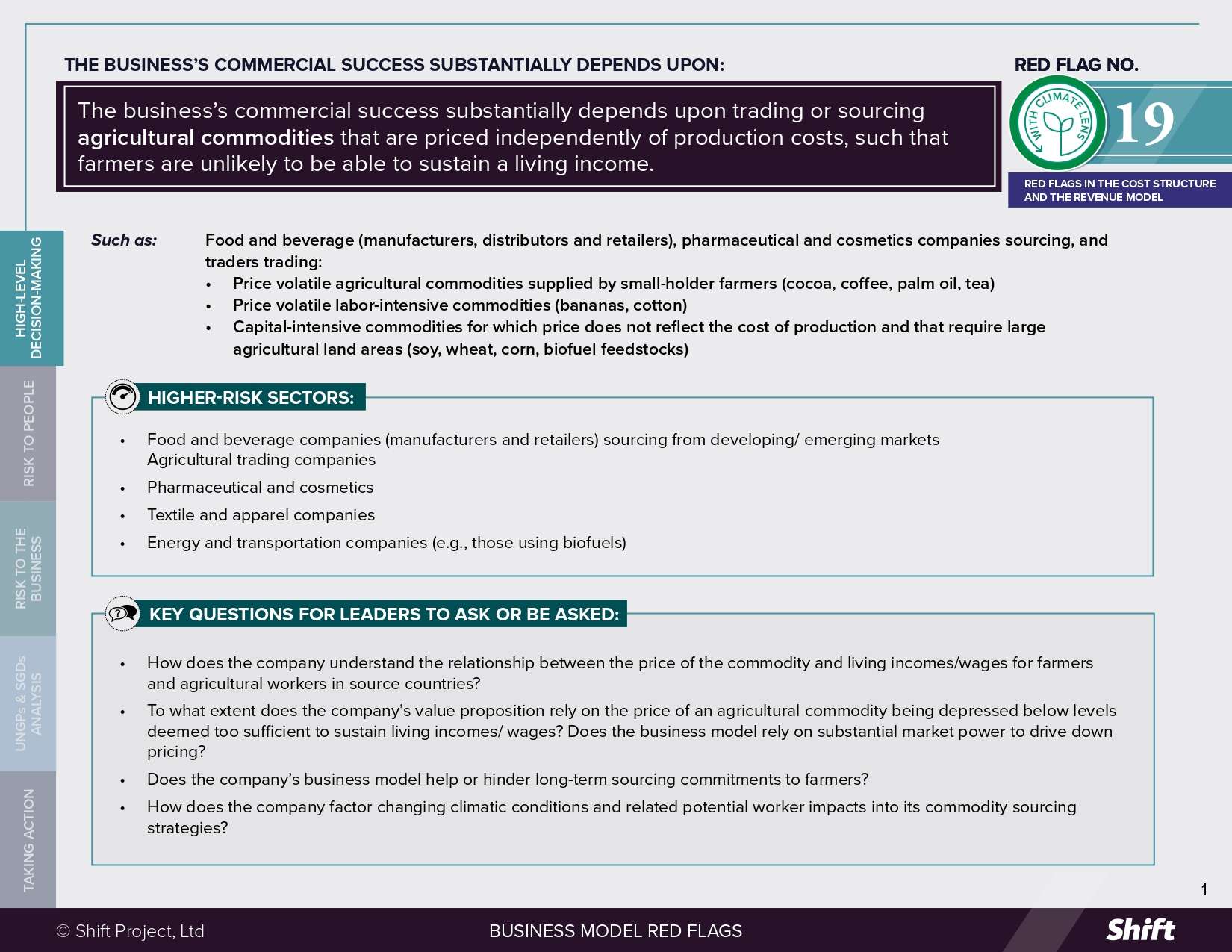

RED FLAG # 19

The business’s commercial success substantially depends upon trading or sourcing agricultural commodities that are priced independently of production costs, such that farmers are unlikely to be able to sustain a living income.

For Example

Food and beverage (manufacturers, distributors and retailers), pharmaceutical and cosmetics companies sourcing, and traders trading:

- Price-volatile agricultural commodities supplied by small-holder farmers (cocoa, coffee, palm oil, tea, milk)

- Price-volatile labor-intensive commodities (bananas, cotton)

- Capital-intensive commodities for which the price does not reflect the cost of production and that require large agricultural land areas (soy, wheat, corn, biofuel feedstocks)

Higher-Risk Sectors

- Food and beverage companies (manufacturers and retailers) sourcing from developing/ emerging markets

- Agricultural trading companies

- Pharmaceutical and cosmetics

- Textile and apparel companies

- Energy and transportation companies (e.g., those using biofuels)

Questions for Leaders

- How does the company understand the relationship between the price of the commodity and living incomes/wages for farmers and agricultural workers in source countries?

- To what extent does the company’s value proposition rely on the price of an agricultural commodity being depressed below levels deemed sufficient to sustain living incomes/ wages? Does the business model rely on substantial market power to drive down pricing?

- Does the company’s business model help or hinder long-term sourcing commitments to farmers?

- How does the company factor changing climatic conditions and related potential worker impacts into its commodity sourcing strategies?

How to use this resource. ( Click on the “+” sign to expand each section. You can use the side menu to return to the full list of red flags, download this Red Flag as a PDF or share this resource. )

Understanding Risks and Opportunities

Risks to People

-

An estimated 1.23 billion people are directly employed in agrifood systems, contributing to food supply through complex value chains. According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), while agrifood systems provide employment around the world, they do not always provide an acceptable standard of living and quality of life. In fact, too often, vulnerable populations are left behind across agrifood systems” and often they “bear the greatest burden of the social hidden costs of agrifood systems.”

-

Farmers and smallholders have limited influence in negotiating terms of trade and capture only 6% of all generated income from the global food system supply chain.

-

A range of structural barriers underlie this disadvantage, at the levels of the supply chain, commodity sector and public policy. ETI notes that business models intersect with these barriers in many ways, including:

-

Consolidation of the market into a limited number of food retailers with substantial market power, that is often used to drive down prices and leave farmers unable to negotiate higher pricing;

-

The effect of lowest cost or “discounter models” in the food retail sector, driving price competition and increased pressure on prices in the supply chain

-

-

Price squeezes on suppliers increase the risk of human and labor rights violations in food and farming supply chains, often affecting the most vulnerable in rural communities, including small-holder farmers, particularly women and migrants. For example, as of September 2022, cocoa farmers in Cote D’Ivoire were earning between 38 and 42 percent of a living income and in Ghana, roughly 40 percent of a living income. The inability of a farmer to provide for his or her family leads to a considerable loss of dignity in some rural communities, increasing marginalization and compounding the risk of human rights impacts.

-

With respect to some commodities, farmers and their families find themselves in a poverty trap: without funds or investment to grow high-quality produce or plan ahead, they face low prices and/or harvest early, reinforcing the poverty cycle.

-

Further, a lack of living income is closely linked to wider human rights abuses in global agricultural supply chains. In sectors like cocoa in West Africa, where many farmers earn far below a subsistence income, families often rely on child labor to meet harvest demands. This income deprivation fuels cycles of poverty, limiting access to education, healthcare, and decent work for future generations. Addressing living incomes for farmers is therefore central to breaking the systemic conditions that enable child labor to persist. Further, without capital to invest in new farming equipment they are unable to upgrade to equipment that is safer, more energy efficient and less labor intensive.

-

Climate change can intensify the impacts resulting from this business model risk in a variety of ways. Climate stresses are increasing the vulnerability of small-scale farmers and their households to poverty. As global and local temperatures increase, smallholder farmers are more frequently facing heat stress, which can impact productivity, as well as farmer health and ability to work. These risks are expected to compound and cascade as temperatures continue to rise. For example, a study published by the World Meteorological Organization projects that in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia, heat stress in a 3°C climate scenario will result in a 30-50% reduction of agricultural labor capacity, which would then increase food prices, making food stuffs increasingly unaffordable for poorer communities.

-

Increased frequency and duration of extreme heat, along with droughts and floods, can result in crop losses, impacting crop production, crop lifetimes, and pricing with corresponding impacts on farmer livelihoods. For certain crops, land suitability will be at risk: for example, analysis from Zurich University of Applied Sciences suggests that climate change will reduce the most suitable existing coffee lands by more than 50% by 2050.

-

While there is evidence of smallholder farmers exploring different adaptation strategies in response to increased climate stress, they face several challenges, including limited access to information, finance, technological options, knowledge, and skill – and, for women farmers, gender discrimination. And without effective and sustained adaptation strategies, worsening climate conditions can make farmers’ earnings even more unpredictable and precarious, further intensifying the impacts of this business model feature.

-

Finally, in response to corporate net zero commitments, company climate mitigation actions that fail to consider impacts on people can also impact agricultural value chains. Pressure to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and move to regenerative agriculture could lead companies to reduce reliance on smallholder farmers within company value chains, adjust sourcing strategies to minimize transportation emissions or place greater emissions reduction requirements on farmers with limited resources, putting further downward pressure on farmer incomes.

Risks to The Business

-

Legal, Financial, Regulatory, Operational and Reputational Risks:

-

Undue price pressure on supply chains in certain geographies can lead to civil society campaigns, resulting in damage to reputation, brand and customer loyalty. For example:

-

Amnesty International’s “Big Palm Oil Scandal” campaign, named several large brands (e.g., Nestle, Colgate-Palmolive, Wilmar) highlighting poor labor practices at the plantations supplying their palm oil.

-

The 2023 Corporate Accountability Lab report on the cocoa supply chain names several multinational cocoa and chocolate companies (e.g., Mars, Nestle, Cargill and Ferrero) and highlights the incongruities between seemingly extravagant corporate capital expenditures with the comparative costs of paying agricultural suppliers a living income.

-

-

Extreme price pressure on farmers can undermine availability of product and stability of supply in the near term; over time it can contribute to an exodus from farming. For example, in Australia, two major Australian supermarkets (Woolworths and Coles) were accused of aggressive negotiating tactics by farmers’ representatives, who claimed that farmers were being “held to ransom by a large corporate duopoly”, which is in turn “contributing to the wide-scale bulldozing of orchards and an industry exodus.” The allegations resulted in significant media scrutiny, public demands to “break up” the large super market chains, a senate inquiry, as well as a government-imposed mandatory Food & Grocery Code of Conduct for retailers and wholesalers with over AUD 5 billion in annual grocery revenue. As of 1 April 2025, breaches of the code face financial penalties (greater of: AUD 10M, 3 times the value of the contravening conduct, or 10% of turnover for the preceding 12 months).

-

-

Business Opportunity:

-

A brand proactively addressing the ways in which commodities are sourced to minimize adverse impacts on people can be rewarded with positive consumer perceptions. For example in a 2023 survey, 79% of consumers said that if a brand’s products bear the Fairtrade International mark that would positively impact their perception of that brand.

-

Proactively addressing human rights risks related to farmer incomes strengthens supply chain resilience, reduces supply disruption risks, bolsters stakeholder trust, and enhances long-term sourcing reliability.

-

What the UN guiding principles say

The UNGPs note that companies should “strive for coherence between their responsibility to respect human rights and policies and procedures that govern their wider business activities and relationships [including] …. procurement practices” (Principle 16, Commentary).

-

Companies sourcing commodities through their supply chain from farmers who receive less than a living income may be directly linked to impacts on the adequacy of the farmers’ standard of living.

-

If a company’s purchasing practices push costs upstream in the supply chain – whether alone or as part of an industry-wide behavior – in ways that prevent farmers from achieving a living income, they contribute to the impacts experienced by farmers.

Possible Contributions to the SDGs

Addressing impacts on people associated with this red flag indicator can contribute to, among other things:

-

SDG 1: Eradication of poverty in all its forms

-

SDG 10: Reduce inequality within and among countries

-

SDG 13: Take Urgent Action to Combat Climate Change and its Impacts, in particular target 13.1 Strengthen resilience and adaptive capacity to climate-related hazards and natural disasters in all countries

Oxfam has noted that, “perpetually low income levels are one of the key reasons why farmers remain stuck in poverty…For many small-scale farmers, significant gaps exist between their actual income and income levels sufficient to ensure a decent standard of living…”. Oxfam cites structural barriers, including at the level of individual supply chains, which reinforce the “significant imbalance between the risks of agriculture shouldered by farmers and their power to shape their own market participation.”

By addressing the impacts on living income from corporate sourcing practices and price influencing, companies can contribute to lifting the poorest people in agriculture into more sustainable livelihoods, and in turn help them to escape poverty and realize their rights, from better health to nutrition to education.

Taking Action

Due Diligence Lines of Inquiry

-

Are our purchasing practices designed to drive down pricing, or do they have the effect of doing so? How do we know?

-

Is the duration of our supply chain commitments/contracts helping or hindering our ability to use our leverage to secure better prices for farmers?

-

Have we explored increasing dialogue with, or forming partnerships with, farmers or cooperatives in our supply chain? Have we sought to understand the real costs associated with production of the commodity, based on their experience?

-

Are we engaging in multi-stakeholder initiatives (MSIs) aimed at addressing human rights impacts with respect to the commodity on which we rely? Where a relevant MSI doesn’t exist, can we learn from such initiatives for other commodities and explore opportunities to create one?

-

Have we explored how to engage and educate our customers if they must absorb some price increase to protect farmer living standards?

-

Are we prepared to experiment – and learn from failures or missteps – in tackling the difficult challenge of livelihoods in supply chains? Can we explore opportunities to promote and facilitate the growth of new forms of business in our supply chain that can channel more resources to farmers (e.g. cooperatives, women-owned enterprises, social enterprises)?

-

Do we understand the ways in which climate variability is impacting our suppliers and the steps we can take to address potential impacts for farmer incomes? What measures are we taking to address climate-related impacts on our suppliers?

Mitigation Examples

* Mitigation examples are current or historical examples for reference, but do not offer insight into their relative maturity or effectiveness.

-

The Farmer Income Lab, launched by Mars, with Dalberg Advisors, Wageningen University and Oxfam USA, is a collaborative effort to identify ways to increase smallholder farmers’ incomes – beginning with Mars’ supply chains in developing countries – and to understand how to create positive outcomes for farmers at scale.

-

Companies participating in the voluntary Sustainable Vanilla Initiative commit to pre-competitive projects to improve quality, product traceability, good market governance and the livelihoods of smallholder farmers who form the foundation of the global vanilla bean trade.

-

Nestle has developed its Income Accelerator Program, which aims to close the living income gap and reduce child labor risks, the progress of which is being independently monitored by the KIT Institute. The program pays cocoa-farming families annual cash incentives for practices like child schooling, agroforestry, and income diversification, with payments split between spouses to boost gender equality and resilience.

-

Tony’s Open Chain, started by Tony’s Chocolonely in 2019, is an industry initiative in which participating cocoa companies sign on to the mission “to ensure cocoa households achieve a living income, eradicate child labor and protect forests by enabling responsible business conduct”. They pledge to source cocoa beans according to Tony’s 5 Sourcing Principles: traceability, higher prices, long-term commitments, strong farmer partnerships, and enhanced quality and productivity.

-

OFI, one of the world’s largest cocoa, coffee, and nut traders, uses its Living Income Calculator to design income generating strategies for farmer groups across several of its sourcing locations and has committed to a living income target of 200,000 farmers achieving a living income and 1 million farmers receiving enhanced livelihood support, both by 2030.

-

McCormick’s Grown for Good program is a third-party verified sustainability standard that directly links sourcing practices to farmer welfare. The company works with their “suppliers to increase the direct economic benefits generated by farmers and to remove unnecessary intermediaries”. The program also provides farmers with services like health insurance, access to finance and access to inputs which can help the farmers improve their yields and profitability and, in turn, build the reliability and resilience of McCormick’s supply chain.

Alternative Models

-

Oxfam has highlighted several examples of alternative models, including:

-

UK company Sainsbury’s Dairy Development Group: farmers have full membership within the group and equal votes in decision making on milk price.

-

Private company Apicultura Lilian, in Honduras: the company has a sourcing strategy focused on establishing a direct link with honey producers; it distributes 10% of its profits to supplier network and provides technical support and inputs to increase yields

-

-

Princes Industrie Alimentari based in Italy is committed to ethical working conditions in the tomato supply chain and ahead of the 2022 harvest season they signed contracts to enhance financial security among growers.

-

In India, the Regenerative Production Landscape Collaborative, initiated by the Laudes Foundation, IDH, and WWF India, offers a model of regenerative agriculture that addresses both livelihood and environmental challenges, such as pesticide pollution and persistent drought. This collaborative works to shift smallholder farmers across Madhya Pradesh from monsoon‑dependent monoculture cotton to regenerative intercropping and vegetable diversification. It brings together government, civil society, farmers, brands (e.g., H&M, Inditex, IKEA, PepsiCo) to drive regenerative practices, improve ecosystem health, and secure supply accountability. Early results report significant improvement in soil health, crop yields and farmer incomes through diversified crops and reduced input costs.

-

Some initiatives appear to aim at “de-commoditization”: An impact investing fund created by Danone, Firmenich, Mars and Veolia with respect to vanilla, offers a 10-year commitment, cooperative and a minimum price, through an “innovative model where farmers and industry players share both the benefits and risks.” The project estimates that 60% of cured vanilla’s value will go back to farmers (compared to initially observed shares of 5% to 20%).

Other tools and Resources

Cocoa

-

Oxfam (2025) Raising the Bar: Supermarkets Must Urgently Address Structural Exploitation of Cocoa Farmers outlines the role supermarkets can play in supporting living incomes for cocoa farmers.

-

Corporate Accountability Lab (2023) There Will be No More Cocoa Here: How Companies are Extracting the West African Cocoa Sector to Death.

-

Wageningen University & Research (2024) High-level analysis of recent and current yield in the West African cocoa sector: Trends, possible causes and recommendations for interventions.

-

Peter Stanbury and Toby Webb’s How to deliver real sustainability in the cocoa sector? Collaborative development governance puts the case for cross-cutting, long-term action.

Coffee

-

Global Coffee Platform is a multistakeholder membership association focused on collective action on local priorities and critical issues for coffee farmers.

Tea

-

Ethical Tea Partnership (2021) Climate Change and Tea explores how climate change is impacting the tea sector, including for the farmers and communities who rely on it for their living.

-

Banerji, Sabita, Willoughby, Robin (2019) Addressing the Human Cost of Assam Tea: An agenda for change to respect, protect and fulfil human rights on Assam tea plantations. Oxfam Policy and Practice.

-

Ethical Tea Partnership’s Responsible Contracting Pilot aims to embed responsible business practices in contracts.

-

Business and Human Rights Resource Center Tea Supply Chain Tracker evaluated companies operating in the tea industry based on their human rights policies and standards.

Multiple commodities

-

Fairtrade International (2024) Climate and the Environment reports on how climate change is eroding farmer incomes across multiple commodities and advocates for minimum pricing floors and living income benchmarks to mitigate these risks.

-

The Living Income Community of Practice aims to increase understanding of living income measurement and the income gaps, identify and discuss strategies for closing the income gap and facilitate collaboration.

-

Oxfam (2018), A Living Income for Small-Scale Farmers: Tackling unequal risks and market power discusses the barriers to raising small-scale former incomes and entry points for change.

-

Oxfam (2018) Fair value: Case studies of business structures for a more equitable distribution of value in food supply chains explores 12 case studies to demonstrate that equitable business structures, such as farmer-owned cooperatives, and business arrangements including long-term and transparent contracts, profit sharing and producer participation in pricing committees, can result in farmers receiving a greater share of the value of the food they produce.

-

FAO (2015) Inclusive Business Models Guidelines for improving linkages between producer groups and buyers of agricultural produce. FAO has developed guidelines that contain, inter alia, useful methodologies for buyers seeking to organize farmers into suppliers, which includes contract farming or out grower schemes.

Citation of research papers and other resources does not constitute an endorsement by Shift of their conclusions.

Business Model Red Flags

Business Model Red Flags  Tool for Indicator Design

Tool for Indicator Design