About the European Commission’s Omnibus Simplification Proposal on EU Sustainability Due Diligence and Reporting Laws

In 2024, the President of the European Commission announced that the Commission would bring forward a proposal to simplify requirements and reduce burdens on smaller companies, including in connection with the recently adopted Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) and the more established Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD). In February 2025, the Commission announced its ‘Omnibus Simplification Proposal’. While the goals are reasonable ones for European Union (EU) policy-makers to pursue, in fact the proposal risks making life more complicated for both large and small companies.

You can read Shift’s initial assessment of the Omnibus Proposal here. In it, we explain how the proposal would make it much harder for companies to ‘know and show’ that they are managing the human rights and environmental risks they face, and leave them on the back foot when they are ‘named and shamed’ by the media and NGOs when things go wrong in their supply chains.

Shift will continue to be actively involved in the Omnibus legislative process based on our mission to advance alignment of influential standards with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. We will regularly share resources and updates here, so please check back in or sign up to our newsletter here.

About the EU Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive

Beginning in 2017, several European states including France, Germany and the Netherlands began to adopt versions of human rights due diligence legislation. This created momentum for the EU to help level the playing field.

In 2022, the EU began negotiating a draft Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) which was finally adopted in May 2024. During this time, Shift’s focus was on ensuring the CSDDD was anchored in the international standards on sustainability due diligence – the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises. Despite limitations with regard to the scope of companies covered under the Directive, and limited obligations with regard to due diligence on downstream impacts, the core content of the final law was substantially aligned with the UNGPs – making it more likely to be both impactful for people and planet and manageable for companies to implement. The Directive provides that EU Member States have two years to transpose it into their national laws. Enforcement would then commence one year later for the first batch of covered companies, with the others following after. The Directive was expected to cover more than 5500 companies. For more information, check out Shift’s responses to Frequently Asked Questions about the CS3D.

How should companies respond to the current regulatory uncertainty?

Given the uncertainties created by the Omnibus Proposal and negotiation process, our advice to companies that want to know how they should respond is simple – keep doing risk-based due diligence in line with the existing international standards. That remains the single best investment companies can make to prepare to meet current and future demands, whether from investors, lenders, customers, civil society or EU policy-makers as this process moves forwards.

Core Resources

Our analysis

5 resources

Frequently Asked Questions about the EU Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive

In this resource, Rachel Davis (Co-Founder), and Ruben Zandvliet (Deputy Director for Standards), answer companies’ frequently asked questions about the new Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive. Since the approval of the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CS3D) by senior officials from EU Member States in Council on 15 March, we’ve received numerous questions from companies […]

Aligning the EU Due Diligence Directive with the International Standards: Key Issues in the Negotiations

Aligning the CS3D with the core concepts in the international standards The EU is currently in the process of negotiating a legal instrument that will establish new corporate human rights and environmental due diligence duties across the single market – the draft Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CS3D). At the heart of the negotiations is […]

Designing an EU Due Diligence Duty that Delivers Better Outcomes

What is the CS3D? Starting in 2022, the European Union has been negotiating a draft Directive on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence (CS3D), with discussions on a final law expected to begin by mid-2023. The draft Directive aims to ensure companies active in the single European market contribute to sustainable development by preventing and addressing negative human rights and environmental impacts. […]

Shift’s Analysis of the EU Commission’s Proposal for a Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive

On 23 February 2022, the European Commission released its ‘Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence. Its overall objective is to ensure that companies active in the internal market contribute to sustainable development …through the identification, prevention and mitigation, bringing to an end and minimization […]

“Signals of Seriousness” for Human Rights Due Diligence

This discussion draft is intended for the consideration of the European Commission and other stakeholders as the Commission develops proposals on mandatory human rights and environmental due diligence (mHREDD) and considers how national regulators would implement any such legislation. Shift is submitting this draft together with our formal response to DG JUST’s consultation on a […]

Previous Comments and Analysis by Shift

- Rachel Davis’ March 2022 COMMENTS to the European Parliament RBC Working Group on the release of the Commission’s proposal

- Our March 2022 ANALYSIS of the Commission’s proposal for a draft Directive

- Our October 2021 Key Design Considerations for the Enforcement of Mandatory Due Diligence, developed in collaboration with the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights

- Our August 2021 viewpoint on how legislating a new standard of conduct CONNECTS TO OUTCOMES FOR PEOPLE

- Our July 2021 viewpoint on the relationship between HUMAN RIGHTS AND ENVIRONMENTAL DUE DILIGENCE

- Our June 2021 viewpoint on the need to include SMEs in the scope of new regulations while allowing them APPROPRIATE FLEXIBILITY

- Our April 2021 recap of the mHRDD debate in Europe (see below)

- Our February 2021 RESPONSE to the European Commission’s initial consultation on the need for an initiative on sustainable corporate governance

Accountability as part of Mandatory Human Rights Due Diligence: Three Key Considerations for Business

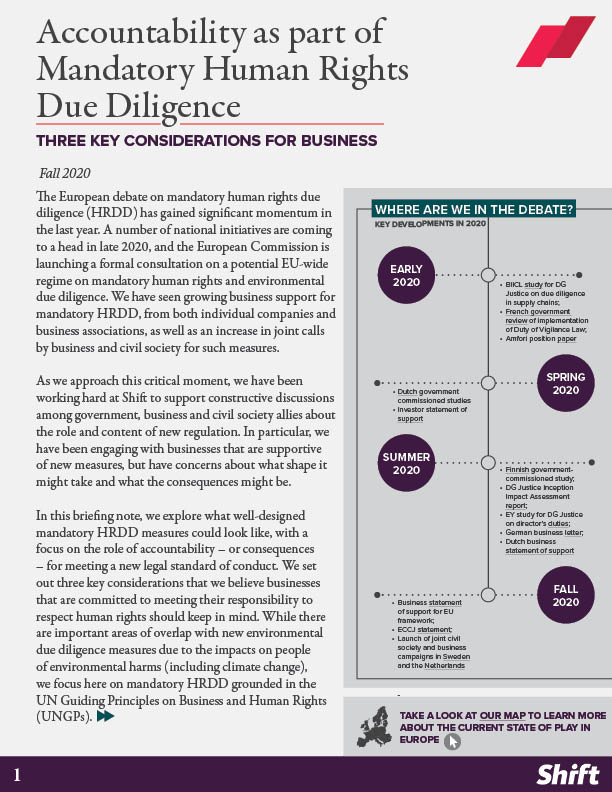

The European debate on mandatory human rights due diligence (HRDD) has gained significant momentum in the last year. A number of national initiatives are coming to a head in late 2020, and the European Commission is launching a formal consultation on a potential EU-wide regime on mandatory human rights and environmental due diligence. We have seen growing business support for mandatory HRDD, from both individual companies and business associations, as well as an increase in joint calls by business and civil society for such measures.

Also Read

October 2020 |

Opening Remarks by John Ruggie at the Conference “Human Rights and Decent Work in Global Supply Chains”

ReadAs we approach this critical moment, we have been working hard at Shift to support constructive discussions among government, business and civil society allies about the role and content of new regulation. In particular, we have been engaging with businesses that are supportive of new measures, but have concerns about what shape it might take and what the consequences might be.

In this briefing note, we explore what well-designed mandatory HRDD measures could look like, with a focus on the role of accountability – or consequences – for meeting a new legal standard of conduct. We set out three key considerations that we believe businesses that are committed to meeting their responsibility to respect human rights should keep in mind:

- The legitimate role of liability in implementing the UN Guiding Principles

- Incentivizing robust HRDD through accountability measures that go beyond liability

- Assessing the quality of a company’s due diligence

“Effective regulation should take account of the legitimate concerns of various stakeholder groups. For mandatory HRDD, that means forging legislation that speaks to businesses’ concerns that liability on its own won’t incentivize the right kinds of practices and behaviors by companies throughout their value chains. But it also has to address the understandable views of civil society that a failure to meet an agreed standard of conduct should result in robust consequences, including a basis for those harmed to seek remedy.”

Rachel davis, vice president of shift

Shift’s Submission on Human Rights Opportunities in the EU Non-Financial Reporting Directive Review Process

In February, the European Commission began seeking stakeholder feedback to inform the revision of the EU Non-financial reporting directive (NFRD) as part of its strategy to strengthen the foundations for sustainable investment.

Shift made this submission as part of the consultation, drawing on our work over several years to strengthen human rights reporting standards in line with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.

Pillar 1

The State Duty to Protect

The first pillar of the Guiding Principles provides recommendations on how states can meet their existing international human rights obligations to protect against business-related human rights abuses by creating an environment that is conducive to business respect for human rights, including by:

- Working to achieve greater legal and policy coherence between their human rights obligations and their actions with respect to business, including by enforcing existing laws, identifying and addressing any policy or regulatory gaps and providing effective guidance to business;

- Fostering business respect for human rights both at home and abroad;

- Taking particular measures where there is a close nexus between the state and business such as ownership or when a state conducts commercial transactions with business (such as through government procurement or the provision of trade or export credit support);

- Helping ensure that businesses operating in conflict-affected areas do not commit or contribute to serious human rights abuses;

- Fulfilling their duty to protect when they participate in multilateral institutions (e.g., World Bank, OECD) with other states.

Keynote Address by John Ruggie at the Conference ‘Business & Human Rights: Towards a Common Agenda for Action’

These remarks were originally delivered by Professor John Ruggie at the Conference ‘Business & Human Rights: Towards a Common Agenda for Action’, on December 2, 2019. The Conference was co-organized by Shift and the Finnish Presidency of the Council of the EU.

Many thanks to the government of Finland for convening this timely and important conference.

It is timely because a new European Parliament has been elected and a new Commission selected. It is important because we live in a turbulent world that challenges foundational premises we had been able to take for granted. The European Union is one of the most significant governance innovations in modern times. It all began modestly, with six countries coordinating their coal and steel sectors in the wake of World War II. Today, the EU – whether it is 27 or 28 – constitutes an economic and social superpower. Now more than ever, the EU needs to think of itself in those terms.

I am pleased that Finland chose business

and human rights as the focus of its EU Presidency and of this

conference. It leads us to address the people part of the people and

planet challenges faced by all humanity. The conference agenda asks the

question: How do we most effectively advance action on the EU level? My

job this morning is to sketch out the backstory to our discussions and

suggest some strategic directions.

Let me begin with the most basic question:

What is business and human rights all about? The answer varies depending on the vantage point. In big-picture terms, it is about the social sustainability of globalization. Some years ago, my favorite boss, Kofi Annan, said: “if we cannot make globalization work for all, in the end it will work for none.” Today, people around the world are telling us that we have fallen short, that the benefits and burdens of globalization have been unequally distributed within and among nations. The result is public resentment and loss of trust in institutions of all kinds.

When seen from the perspective of enterprises, business and human rights is about ways they can recover trust and manage the risk of harmful impacts. Undeniable progress has been achieved by individual firms, business associations, and even sports organizations. But not enough, and not by enough of them.

For governments, business and human rights is at the core of new social contracts they need to construct for and with their populations. This includes decent work and living wages, equal pay for work of equal value, social and economic inclusion, education suitable to the needs and opportunities of the 21st century, and effective social safety nets to buffer unexpected shocks to the economy or the person.

For governments, business and human rights is at the core of new social contracts they need to construct for and with their populations.

For the individual person whose rights are impacted by enterprises, business and human rights is about nothing more – but also nothing less – than being treated with respect, no matter who they are and whatever their station in life may be, and to obtain remedy where harm is done.

My second point is to remind us that

formal international recognition of business and human rights as a

distinct policy domain is relatively recent. At the UN level, the first

and thus far only formal recognition dates to 2011, when the Human

Rights Council unanimously endorsed the Guiding Principles on Business

and Human Rights.

The UN Guiding Principles rest on three pillars:

The state duty to protect against human rights harm by third parties, including business; the responsibility of enterprises to respect human rights, regardless of whether states meet their own obligations; and the need for greater access to remedy

by people whose human rights have been abused by business conduct. The

OECD Guidelines on Multinational Enterprises quickly incorporated Pillar

II virtually verbatim.

The UNGPs comprise 31 Principles and Commentary on what each means and implies for all actors: states, enterprises, as well as affected individuals and communities. They are not merely a text. They were intended to help generate a new regulatory dynamic, one in which public and private governance systems, corporate as well as civil, each come to add distinct value, compensate for one another’s weaknesses, and play mutually reinforcing roles—out of which a more comprehensive and effective global regime might evolve.

That brings me to the key issue of strategy – how to reinforce and add to this transformative dynamic. The Guiding Principles embody two core strategic concepts: advocating a “smart mix of measures,” and using “leverage.” I’ll take them up in turn.

We often hear the term “smart mix of measures” being employed to mean voluntary measures alone. But that gets it wrong. Guiding Principle 1 says that states must have effective legislation and regulation in place to protect against human rights harm by businesses. Guiding Principle 3 adds that states should periodically review the adequacy of such measures and update them if necessary. They should also ensure that related areas of law, for example corporate law and securities regulation, do not constrain but enable business respect for human rights. So, a smart mix means exactly what it says: a combination of voluntary and mandatory, as well as national and international measures.

We often hear the term “smart mix of measures” being employed to mean voluntary measures alone. But that gets it wrong. (…) A smart mix means exactly what it says: a combination of voluntary and mandatory, as well as national and international measures.

A number of EU member states and the EU as a whole have begun to put in place mandatory measures that reinforce what previously was voluntary guidance to firms on corporate responsibility. These include reporting requirements regarding modern slavery, conflict minerals, and non-financial performance more broadly, as well as human rights and environmental due diligence. Such initiatives are aligned with the spirit of the UNGPs, and they are important steps in adding “mandatory measures” into the mix. Still, many leave a lot to the imagination – of company staff, consulting firms, and civil society actors among others. More should be done to specify what meaningful implementation looks like, in order to avoid contributing to the proliferation of self-defined standards and storytelling by firms. Also, with limited exceptions currently no direct consequences follow from non-compliance. Nevertheless, the ascent of Pillar I is underway.

Using leverage

A second key strategic concept embedded in the UNGPs is “leverage.” Here are three examples of how leverage can play into the core question of how most effectively to advance implementation at the EU level.

- First, individual member states and the EU as a whole are economic actors: they procure goods and services, provide export credit and investment insurance, issue official loans and grants, and so on. Each agency involved has particular objectives of its own, to be sure. But in all cases, they should consider the actual and potential human rights impacts of beneficiary enterprises with which they engage.

- Second, the UNGPs state that the responsibility of enterprises to respect human rights requires that they avoid causing, contributing to, or otherwise being linked to adverse impacts, and to address them when they occur. This extends throughout their value chains. Of course, all firms, including the suppliers of goods and services within global value chains, have the same responsibility to respect. But parent companies and companies at the apex of producer- or buyer-led value chains should also use whatever leverage they have in relation to their subsidiaries, contractors, and other actors in their network of business relationships. They should establish clear policies and operational procedures that embed respecting rights throughout their entire value chain system. Where leverage is limited it may be possible to increase it, for example by providing incentives or collaborating with other actors.

In turn, home, as well as host states of multinational enterprises, have significant roles to play through laws and regulations that enable and support private international ordering of this sort. Global value chains are exceedingly complex. If parent or lead companies fear that they may be held legally liable for any human rights harm anywhere within their value chains, irrespective of the circumstances of their involvement, it would create the perverse incentive to distance themselves from such entities. It is important that regulation gets the balance right. - A third way in which leverage can play into effective implementation at the EU level is by reinforcing positive trends already underway in the business community, but which need strengthening. Perhaps the most important instance today is ESG investing – investment decisions that combine environmental, social, and governance criteria with financial analytics. ESG investing now accounts for $31 trillion of all assets under management worldwide, or one-quarter of the global total. And while it may not be known to many investors themselves, the S in ESG is all about human rights. It seeks to assess how firms conduct themselves in relation to the broad spectrum of internal and external stakeholders – workers, end-users, and communities. It typically includes such categories as health and safety, workplace relations, diversity and social inclusion, human capital development, responsible marketing and R&D, community relations, and company involvement in projects that may affect vulnerable populations in particular.

But here is the problem: it is now generally agreed that a major impediment to the further rapid growth in ESG investing is the poor quality of ESG data provided by raters. Common taxonomies and templates are still in their infancy and evolving haphazardly even as demand for ESG products is increasing. This poses problems for investors who seek ESG opportunities and may be paying a high price for flawed data, as well as for companies striving to improve their practices that go unrecognized. The problem is especially severe in the S category – addressing human rights-related issues.

In short, a great variety of opportunities exists for exercising leverage in order to generate further positive developments in business and human rights.

The EU has developed a comprehensive taxonomy for investment on climate-related standards, indices, and disclosure. That should have a significant impact for strengthening the E in ESG. Also issuing official guidance to the S in ESG investing, making clear its human rights bases, could have a transformative effect on global capital markets.

In short, a great variety of opportunities exists for exercising leverage in order to generate further positive developments in business and human rights.

Allow me briefly to add two thoughts in closing.

The first is that business and human rights, by definition, is a domain that requires horizontal vision and cross-functional collaboration – whether within companies, governments, or the EU. Within the European Commission the task has been largely left to the External Action Service, with the support of other directorates-general. That is too narrow a lens to do justice to the broad array of challenges, and to have the impact that could be achieved. One of the singular contributions of National Action Plans for implementing the Guiding Principles is that they have required the whole of governments, for the first time ever, to consider business and human rights as a single policy space. The same holds true at the EU level.

My other concluding thought concerns the ongoing negotiations on a binding business and human rights treaty in Geneva. International legalization is both inevitable and desirable to help level the playing field in a world of global business. In fact, at the conclusion of my mandate in 2011, I proposed that governments negotiate a targeted legal instrument addressing business involvement in gross human rights violations, coupled with the need for greater cooperation between states to provide remedy. Some parties objected on the grounds that this did not go far enough, others that it went too far. It became the only one of my recommendations that did not get adopted.

International legalization is both inevitable and desirable to help level the playing field in a world of global business.

The current treaty process began in 2014. From the outset, I expressed my doubts about attempting to shoehorn the entire business and human rights domain into a single, overarching treaty. In my judgment, this is far too complex and too contested a domain for such an endeavor to produce meaningful results. Indeed, the risk is that if it were to “succeed” in the sense of being adopted by some minimum required number of states, it would be by locking in lower expectations and fewer incentives for innovative practical approaches than exist today. Nothing I have seen in the five years of negotiations suggest otherwise.

Having said all that, I do find it puzzling that the EU has taken no substantive position in these treaty negotiations. It is puzzling because the EU was an early supporter of the “smart mix of measures” idea. This leads me once again to thank the government of Finland for bringing business and human rights to the forefront of its EU Presidency, with the aim of contributing to a common agenda for action. I very much hope that Finland’s successors – as well as the Commission and Parliament – will continue on this path.

Thank you for your attention, and I look forward to our discussions.

The Role of Regulation in a Mix of Measures to Foster Responsible Business Conduct

This panel was moderated by our Vice President, Rachel Davis. The panelists were:

- Nina Norjama, Director of Social Responsibility at UPM

- Salla Saastamoinen, Director for Civil and Commercial Justice at DG Just

- Filip Gregor, Head of Responsible Companies Section at Frank Bold

- Virginie Mahin, Global Social Sustainability and Human Rights Lead at Mondelez

Let’s Talk Mandatory Measures: Supporting a Meaningful Discussion Among all Stakeholders

Also Read

February 2019 |

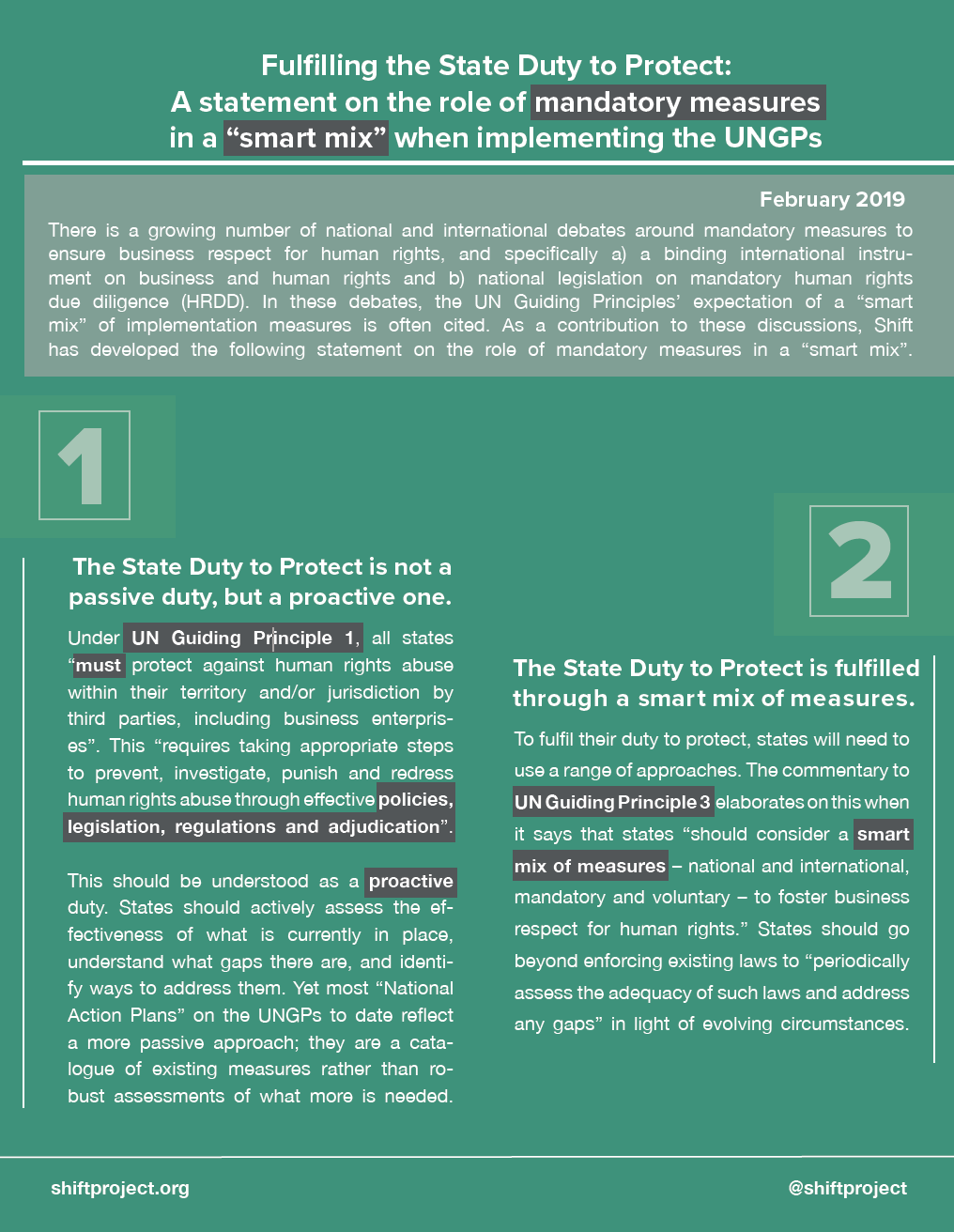

Fulfilling the State Duty to Protect: A Statement on the Role of Mandatory Measures in a “Smart Mix”

ReadUnder Pillar 1 of the UN Guiding Principles, all states “must protect against human rights abuse within their territory and/or jurisdiction by third parties, including business enterprises”. To do so, states “should consider a smart mix of measures – national and international, mandatory and voluntary – to foster business respect for human rights.”

Yet despite this encouragement to consider them, mandatory measures have not been a central part of the mix considered by states in the initial years of UNGPs implementation, outside of certain reporting requirements. That is now changing, particularly in Europe. A growing number of states are actively considering the use of mandatory due diligence measures to advance business respect for human rights.

In France, the Netherlands, Germany, Finland, the UK, Norway and Switzerland, we see governments and legislatures adopting or exploring mandatory measures as part of a mix of policy tools to incentivize business respect for human rights. In a growing number of cases, these measures go beyond reporting obligations to encompass comprehensive human rights due diligence. Continue reading…

“The UNGPs always envisaged that states would adopt a smart mix of measures – voluntary and mandatory – to ensure that businesses respect human rights. We’ve heard the phrase a lot over the last eight years, but it’s mostly been used to describe voluntary measures and states have generally been less willing to explore the mandatory part of the picture. That is now starting to change. As the company, government and civil society voices highlighted here show, there is a growing consensus that we need to get better at talking about what mandatory measures could look like. At Shift, we have made it a priority to support this conversation.”

Rachel Davis – Vice President of Shift

Business and Human Rights Meets Behavioral Science: A Background Note

This pre-read for our April 26th consultation in London provides a brief overview of current thinking in behavioral science, and ways we might apply that thinking in a business and human rights context to improve outcomes for people.

John Ruggie Letter to European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker

A copy of this letter was sent to European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker on February 24, 2017. Click the download link above to view the original letter.

Dear President Juncker,

I write as the former UN Secretary-General’s Special Representative for Business and Human Rights and the author of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, which the UN Human Rights council endorsed unanimously in 2011.

My reason for writing is to express concern that this agenda seems today to be increasingly set aside by the European Commission. An EU Action Plan on CSR/responsible business conduct that has long been promised is yet to emerge, despite two calls last year from all Member States for one to be issued. Indeed, work across Directorates-General that could and should support business respect for human rights appears not to have materialized, or has been stalled altogether.

In the past, leadership from the European Commission alongside other EU institutions has been exceedingly important, helping to drive action across Member State governments, industry associations, investor groupings and other institutions within and beyond Europe. In 2011 the European Commission exercised important leadership in its Communication on Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), setting out a new, clear and simple definition of CSR, namely, “the responsibility of enterprises for their impacts on society.” The Directive stated the Commission’s expectation that all European enterprises should “meet the corporate responsibility to respect human rights, as defined in the UN Guiding Principles.” Among other actions, it announced plans for a legislative initiative on non-financial reporting, which resulted in the directive of 2014 that came into force in January, and which has widely been hailed as a significant contribution to supporting responsible business conduct.

Today, EU leadership is needed as never before. As I observed in my keynote remarks at a G-20 meeting on employment and labor rights in Hamburg just last week, former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan warned already in 1999, in a speech to the World Economic Forum, that unless globalization has strong social pillars it will be fragile and vulnerable—“vulnerable to backlash from all the ‘isms’ of our post-cold war world: protectionism; populism; nationalism; ethnic chauvinism; fanaticism; and terrorism.” If we cannot make globalization work for all, he added on another occasion, in the end it will work for none.

The prescience of this statement is striking today. Now more than ever, we need governments and business to work together to ensure that those most vulnerable to negative impacts from business activities and globalized supply chains are protected and respected. Never has it been more imperative to understand that business’s single greatest contribution to the ‘people part’ of sustainable development should be through efforts to embed respect for human rights across their operations and value chains.

The G7 recognized this in its 2015 Elmau Declaration where leaders underlined the importance of promoting labor rights, decent working conditions and environmental protection in global supply chains. They expressed strong support for the UN Guiding Principles, welcomed efforts to set up substantive National Action Plans for their implementation, and urged the private sector to implement human rights due diligence.

At this critical time when the fate of globalization itself is at stake, the European Union’s voice is needed on the world stage to reiterate these messages clearly and constructively. Yet, as noted, the anticipated EU Action Plan on implementation of the UNGPs has still not been issued. Commission papers on the SDGs seem divorced from any understanding of the central role that respect for human rights must play in the private sector’s contribution to that agenda. And the Commission’s draft guidance to companies on the non-financial reporting directive dilutes and undermines the language of the UN Guiding Principles, provides negligible guidance on the human rights content of the directive, and fails to reference the sole reporting framework – the UNGP Reporting Framework – that is precisely tailored to help companies improve their human rights disclosure fully in line with the UNGPs.

The Commission’s past leadership on responsible business conduct, and in particular on business and human rights, had a catalytic effect on a whole range of actions, across the EU and beyond, that brought substantive progress in business practices. I respectfully urge you and your colleagues to renew that leadership and help build the foundations for a socially sustainable development without which neither our societies nor our businesses can thrive.

As you know well, we live at a pivotal moment in post-World War II history. Globalization itself is at risk unless and until its social pillars can be significantly strengthened. None of us, least of all the EU, should want a roll-back into the mercantilism that has had such destructive consequences in past eras. Responsible business conduct is a central building block of a socially sustainable globalization. And the EU can and should be a central actor in advancing this aim.

Very truly yours,

John G. Ruggie

ESG Toolkit for Fund Managers: Briefing Note on Human Rights

This resource, developed with support from Shift, explains the relationship between human rights and traditional environmental and social due diligence. It aims to provide fund managers with a practical introduction to human rights issues that may be relevant to their investments. It gives fund managers:

- A clear understanding of what human rights risks and impacts are, why they are important and how they relate to traditional environmental and social (E&S) risks and impacts;

- A practical approach to integrating human rights lens into existing E&S due diligence approaches, aligned with international standards.