UNGPs: Remedy

Pillar 3

Even where states and business do their best to implement the Guiding Principles, negative human rights impacts may still result from a company’s operations. Therefore, affected people need to be able to seek redress through effective judicial and non-judicial grievance mechanisms. The third pillar of the Guiding Principles sets out such mechanisms can be strengthened by both states and businesses:

- As part of their duty to protect, states must take appropriate steps to ensure that when abuses occur, victims have access to effective judicial and non-judicial state-based grievance mechanisms;

- Non-state-based grievance mechanisms should complement state-based mechanisms. This includes mechanisms at the operational level (meaning that companies are involved in implementing them), at a national level, or as part of multistakeholder initiatives or international institutions;

- All non-judicial grievance mechanisms should meet key effectiveness criteria by being legitimate, accessible, predictable, equitable, transparent, rights-compatible, a source of continuous learning, and (in the case of operational-level mechanisms) based on dialogue and engagement.

Business and Human Rights Meets Behavioral Science: A Background Note

This pre-read for our April 26th consultation in London provides a brief overview of current thinking in behavioral science, and ways we might apply that thinking in a business and human rights context to improve outcomes for people.

Business and Human Rights in New Zealand

This series took place the week of August 8, 2016 as part of the New Zealand Human Rights Commission inaugural Business and Human Rights Forum.

In collaboration with the New Zealand Human Rights Commission and the New Zealand Superannuation Fund, Shift is pleased to have delivered an education and awareness series about the Guiding Principles for government representatives, parliamentarians, investors, directors, CEOs, company practitioners and civil society representatives in New Zealand. The series took place in August 2016.

Topics that were addressed during the weeklong series in Wellington and Auckland include global uptake of the Guiding Principles, various governments’ actions on business and human rights including in the areas of procurement and disclosure, sharing of leading practices by investors in assessing human rights risks, the role of board directors in overseeing their company’s management of human rights, and exploration of specific business and human rights risks in the New Zealand context. The Australian Human Rights Commission also participated in the program as part of their collaboration with the Commission of New Zealand.

Corporate Accountability for Human Rights Abuses: A Guide for Victims and NGOs on Recourse Mechanisms

The summary is excerpted from the resource.

Summary

With this guide, the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) seeks to provide a practical tool for victims, and their (legal) representatives, NGOs and other civil society groups (unions, peasant associations, social movements, activists) to seek justice and obtain reparation for victims of human rights abuses involving multinational corporations. To do so, the guide explores the different judicial and non-judicial recourse mechanisms available to victims.

In practice, strategies for seeking justice are not limited to the use of recourse mechanisms, and various other strategies have been used in the past. Civil society organisations have for instance set up innovative campaigns on various issues such as baby-milk marketing in Global South countries, sweatshops in the textile industry profiting multinationals or illicit diamond trafficking fuelling conflicts in Africa. Such actions have yielded results and can turn out to be equally (or even more) effective than using formal channels. While this guide will not focus on such strategies, they are often used alongside and reinforce the use of recourse mechanisms. The main focus of this guide is violations committed in third countries by or with the support of a multinational company, its subsidiary or its commercial partner. Hence, the guide focuses in particular on the use of extraterritorial jurisdiction to strengthen corporate accountability.

This guide does not address challenges specifically faced by small and medium-size enterprises. While all types of enterprise play a crucial role in ensuring respect for human rights, we focus on multinational groups. At the top of the chain, it is considered that they have the power to change practices and behaviours, that their behaviour conditions the rest of the chain and that they are in a position to influence their commercial partners, including small and medium-size enterprises. The guide is comprised of five sections. Each examines a different type of instrument.

The first section looks at mechanisms to address the responsibility of States to ensure the protection of human rights. International and regional intergovernmental mechanisms of quasi-judicial nature are explored, namely the United Nations system for the protection of human rights (Treaty Bodies and Special Procedures), the International Labour Organisation complaint mechanisms and regional systems for the protection of human rights at the European, Inter-American and African levels, including possibilities provided by African economic community tribunals.

The second section explores legal options for victims to hold a company liable for violations committed abroad. The first part analyses opportunities for victims to engage States’ extraterritorial obligations, e.g., to seek redress from parent companies both for civil and criminal liability. The section then goes on to explore the promising yet still very limited windows of opportunity within international tribunals and the International Criminal Court. The guide sets out the conditions under which courts of home States of parent companies may have jurisdiction over human rights violations committed by or with the complicity of multinationals. The obstacles that victims tend to face when dealing with transnational litigation — which are numerous and important — are highlighted. While this section does not pretend to provide an exhaustive overview of all existing legal possibilities, it emphasizes different legal systems, mostly those of the European Union and the United States. In addition to practical considerations, this choice is also justified by the fact that parent companies of multinational corporations are often located in the US and the EU (although many are now based in emerging countries); the volume of legal proceedings against multinationals head-quartered in these countries has increased; and, these legal systems present interesting procedures to hold companies (or their directors) accountable for abuses committed abroad.

The third section looks at mediation mechanisms that have the potential to address directly the responsibility of companies. With a particular focus on the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and the National Contact Points countries set up to ensure respect of the guidelines, the section looks at the process, advantages and disadvantages of this procedure. The section also briefly highlights developments within National Human Rights Institutions and other innovative ombudsman initiatives.

The fourth section touches upon one of the driving forces of corporate activities: the financial support companies receive. The first part reviews complaints mechanisms available within International Financial Institutions as well as regional development banks that are available to people affected by projects financed by these institutions. Largely criticized by civil society organisations in the last decades, these institutions have faced increased pressure to adapt their functioning for greater coherence between their mandate and the projects they finance. Most of the regional banks addressed in this guide have gone through recent consultation processes and subsequent changes of their policies, standards and structure of their complaint mechanisms. Their use presents interesting potential for victims. The second part looks at available mechanisms within export-credit agencies, as public actors are being increasingly scrutinized for their involvement in financing projects with high risks of human rights abuses. Not forgetting the role private banks can play in fuelling human rights violations, the third part of this section addresses one initiative of the private sector, namely the Equator Principles for private banks. The fourth and last part of this section discusses ways to engage with the shareholders of a company. Shareholder activism is an emerging trend that may represent a viable way to raise awareness of shareholders on violations that may be occurring with their financial support. Even more important, the increasing attention paid by investors (in particular institutional investors) to environmental, social and governance criteria can be a powerful lever.

Last but not least, the fifth section explores voluntary initiatives set up through multistakeholder, sectoral or company-based CSR initiatives. As mentioned above, various companies have publicly committed to respect human rights principles and environmental standards. As far as implementation is concerned, a number of grievance mechanisms have been put in place and can, depending on the context, contribute to solve situations of conflict. Interestingly, such commitments may also be used, including through legal processes by victims and other interested groups such as consumers to ensure that companies live up to their commitments. This section provides an overview of such avenues.

Improving Accountability and Access to Remedy for Victims of Business-Related Human Rights Abuse

Shift supported two rounds of workshops with member states that fed into this report’s development, particularly the recommendations on cross-border cases. The overview below is excerpted from the report.

Overview

The present report sets out guidance to improve accountability and access to remedy for victims of business-related human rights abuses, following the Accountability and Remedy Project of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) and in response to the request by the Human Rights Council in its resolution 26/22.

The report comprises two parts. The first part provides an introduction to the guidance, including an explanation of its scope, potential usage and important cross-cutting contextual issues. This is followed, in the annex, by the guidance itself, which takes the form of “policy objectives” for domestic legal responses, supported by a series of elements intended to demonstrate the different ways in which States can work towards meeting those objectives in practice. The report is complemented by an addendum (A/HRC/32/19/Add.1), prepared as a companion to the guidance, providing additional explanation and context drawn from the two-year research process of OHCHR.

Accountability and access to remedy: the urgent need for action

Business enterprises can be involved with human rights abuses in many different ways; because of the adverse impacts that business enterprises may cause or contribute to through their own activities, or by virtue of their business relationships. Ensuring the legal accountability of business enterprises and access to effective remedy for persons affected by such abuses is a vital part of a State’s duty to protect against business-related human rights abuse.

At present, accountability and remedy in such cases is often elusive. Although causing or contributing to severe human rights abuses would amount to a crime in many jurisdictions, business enterprises are seldom the subject of law enforcement and criminal sanctions.

Human rights impacts caused by business activities give rise to causes of action in many jurisdictions, yet private claims often fail to proceed to judgment and, where a legal remedy is obtained, it frequently does not meet the international standard of “adequate, effective and prompt reparation for harm suffered”.

State-based judicial mechanisms are not the only means of achieving accountability and access to remedy in cases of business-related human rights abuses. Other possibilities may include State-based non-judicial mechanisms and non-State grievance mechanisms, such as operational level grievance mechanisms. However, effective State-based judicial mechanisms are “at the core of ensuring access to remedy”.

Those seeking to use judicial mechanisms to obtain a remedy face many challenges. While those challenges vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, there are persistent problems common to many jurisdictions. These include fragmented, poorly designed or incomplete legal regimes; lack of legal development; lack of awareness of the scope and operation of regimes; structural complexities within business enterprises; problems in gaining access to sufficient funding for private law claims; and a lack of enforcement. Those problems have all contributed to a system of domestic law remedies that is “patchy, unpredictable, often ineffective and fragile”.

The challenges are exacerbated in cross-border cases. While many domestic legal regimes focus primarily on within-territory business activities and impacts, the realities of global supply chains, cross-border trade, investment, communications and movement of people are placing new demands on domestic legal regimes and those responsible for enforcing them.

The experiences of those seeking remedy suggest that there remain serious deficiencies in the implementation by many States of their international obligations with respect to access to remedy. The right to an effective remedy for harm is a core tenet of international human rights law. The obligations of States with respect to this right have been reflected in the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights: Implementing the Protect, Respect and Remedy Framework in terms of a “State duty to protect” against business-related human rights abuses, of which providing access to an effective remedy is an integral part.

Rectifying these deficiencies — which, in many cases, are rooted in wider social, economic and legal challenges — will not be straightforward. It will require concerted and multifaceted efforts from all States, encompassing actions relating to law reform and legal development, improvements to the functioning of judicial mechanisms, law enforcement, policy development and closer international cooperation. However, this is essential work towards realizing the imperatives of accountability and remedy for business-related human rights abuses.

How to Do Business With Respect for Children’s Right to Be Free From Child Labour

This guidance was developed with input from companies and other stakeholders participating in the ILO’s Child Labour Platform. | Learn about the collaboration that supported the development of this resource.

For companies concerned about child labor connected to their business operations, particularly in global value chains, this comprehensive guidance walks readers through each step of implementing the Guiding Principles. It features an explanation of what constitutes child labor, foundational explanations of Guiding Principles elements, case studies, discussions about common dilemmas, diagnostic questions and tips about pitfalls to avoid. It builds on prior guidance from the ILO and IOE about how to prevent child labor in a company’s own operations, and focuses on the expectations of the Guiding Principles when it comes to preventing and addressing child labor that is several tiers removed in the supply chain. It includes a series of “hard questions” responding to real challenges that companies face.

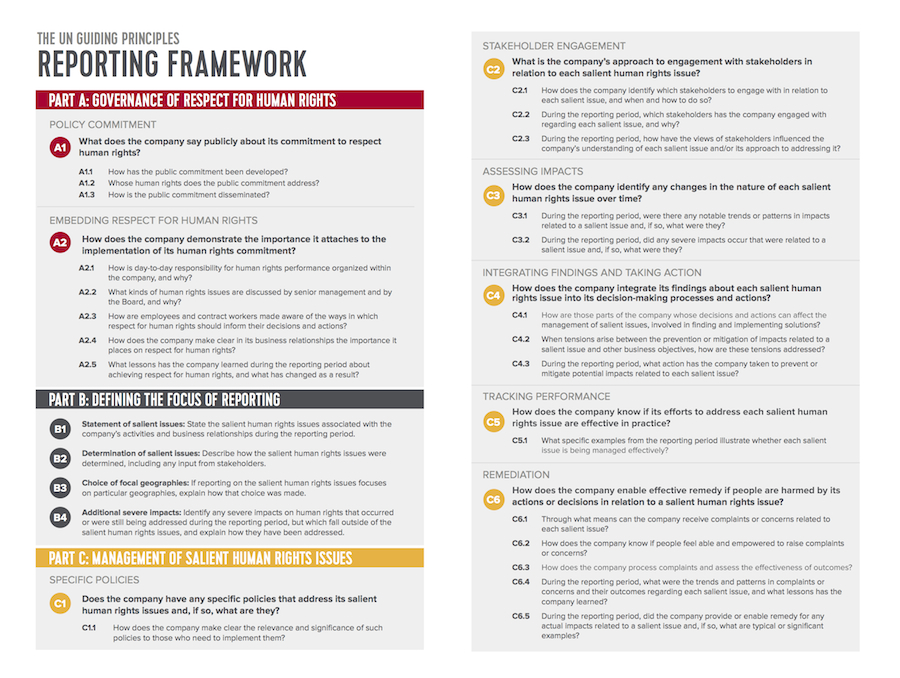

UN Guiding Principles Reporting Framework

This resource is available in multiple languages. Click here to see which translations are available or in progress.

Whether your company is ready to report on its human rights management or is just trying to figure out where to get started, the UNGP Reporting Framework is a powerful tool for both performance and disclosure. Its 31 “smart” questions guide a company through the steps it should be taking to manage and report on its salient – or leading – human rights risks. The Framework was developed over a nearly two-year period through an extensive multistakeholder consultation process. | Learn more about the process of its development | Learn about our current reporting program

The UNGP Reporting Framework was developed through a joint initiative of Shift and international accountancy firm Mazars and is backed by an investor coalition of 87 investors with over $5.3 trillion assets under management, calling on companies to use the Reporting Framework.

The UNGP Reporting Framework has a dedicated website that includes the online version of the Reporting Framework and its two supporting guidances on implementation and assurance, as well as additional resources including an explanation of salient human rights issues, interviews with companies that use the Reporting Framework and a database of corporate reporting mapped to the expectations of the Guiding Principles.

Guidance for Companies on Respecting the Human Rights to Water and Sanitation

This guidance was developed with input from companies participating in the UN Global Compact’s CEO Water Mandate. | Learn more about the collaboration.

The summary below is excerpted from the resource.

Summary

This guidance aims to help companies (particularly heavy water users) translate their responsibility to respect the human rights to water and sanitation (HRWS) into their existing water management policies, processes, and company cultures.

What are the rights to water and sanitation?

- The human right to water entitles everyone to sufficient, safe, acceptable, physically accessible, and affordable water for personal and domestic (household) use.

- “Sanitation” is defined as a system for the collection, transport, treatment, disposal, or reuse of human excreta and associated hygiene. The human right to sanitation entitles everyone to sanitation services that are safe, socially and culturally acceptable, secure, hygienic, physically accessible and affordable, and that provide privacy and ensure dignity.

The main audiences for this guidance are staff with responsibility for human rights and those with responsibility for water stewardship within companies. Both large and small companies should find the guidance useful, but it should be particularly relevant for those with heavy water use in their operations.

In addition, the guidance should be of use to other stakeholders, including representatives of states, civil society organizations working on water and sanitation or on broader human rights issues, investors, international organizations, and others who have an interest in supporting, incentivizing, or requiring companies to meet their responsibility to respect the HRWS.

Translating Impacts on People Into Human Rights and Water Stewardship Terms

What is different when a company brings a human rights lens to its water management efforts? At its core, this means focusing on water-related risks to people rather than water-related risks to the business. This means that company efforts to understand their actual and potential impacts need to take full account of the severity of such impacts on “affected stakeholders,” as defined in the Guiding Principles. This could include workers, local community members, or other individuals or groups whose rights may be negatively affected. These impacts may involve the HRWS, but they may also have an effect on other human rights, such as the rights to health, life, and food. They may also have particular implications for individuals or groups who are at heightened risk of marginalization or vulnerability, who are entitled to additional protections under international human rights law.

Many impacts on the HRWS start as less severe social or environmental impacts, so it can be helpful to consider impacts as existing on a continuum. Preventing less severe social or environmental impacts can therefore help prevent negative impacts on the HRWS, as well as prevent negative impacts on other human rights.

Building the Capacity of OECD National Contact Points

Over a period of several years, Shift supported several National Contact Point (NCP) systems to help them better fulfill their role as part of the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises. The Guidelines are closely aligned with the Guiding Principles when it comes to the expectations of businesses to respect human rights.

This work included:

- Supporting the Danish National Contact Point — the Mediation and Complaints-Handling Institution for Responsible Business Conduct — as it undertook a peer review process. This built on Shift’s previous work supporting the Norwegian NCP as it underwent a similar review in early 2014.

- In 2014, Shift also provided expert support to the OECD Secretariat to conduct a range of capacity building workshops and activities with NCPs. Shift partnered with the Consensus Building Institute in this work. Specific, we delivered:

- A workshop to build the mediation skills and capacity of the Nordic group of NCPs in Oslo, Norway;

- The first “horizontal peer review” session among the NCPs at their annual meeting in Paris in June 2014, focused on strengthening good practices and sharing learning on handling the initial assessment phase of specific instances;

- A capacity building workshop with the Middle East and North African group of NCPs (Egypt, Jordan, Morocco and Tunisia) in Rabat, Morocco;

- A workshop to build the mediation skills and capacity of the Latin American group of NCPs in Santiago, Chile.