Action to address climate change is urgent and essential for our shared future.

This action should shape better lives for all, not leave the poorest and most marginalized left out and worse off. We already see the consequences of today’s high levels of inequality all around us in social polarization, political backlash, economic protectionism and instability. Climate action that fuels these dynamics will only increase opposition to the kinds of changes we need to make to build a more sustainable future. Instead, we need to achieve what is termed a ‘just transition’ – a transition to a low carbon and climate-resilient future that minimizes harm to vulnerable workers, communities and consumers.

Companies, standard setters and financial institutions increasingly recognize the need to bring a human rights perspective to climate action in service of a just transition. And standard-setters are already reflecting these expectations in the laws, regulations and other standards they develop. We see more and more organizations using narrative – or ‘qualitative’ – indicators to describe how human rights considerations are integrated into companies’ efforts to mitigate and adapt to climate change. However, descriptions alone will not enable companies and others to know just how successful these efforts are in practice. We are missing the quantitative metrics that are also needed to measure what is working and what isn’t, to know which are the successful approaches that should be scaled and replicated, and to be able to account for the results.

Shift has been exploring the opportunity to build broad consensus around a core set of quantitative, sector-agnostic metrics that can supplement qualitative indicators and help provide the full picture necessary to assess the ‘justness’ of the climate transition.

We aim to keep this a simple set of sector-agnostic metrics that does not – because it cannot – address all issues and variations. We hope that they can then be built on further in the future to meet the specific circumstances and needs of different sectors, with their differing roles in achieving a just transition, and the differing local contexts in which they operate.

We will also need to keep these initial metrics within the realm of data that can reasonably be gathered and provided by companies, while recognizing – and hoping – that the art of the possible will improve over time. They should be capable of being applied in the context of full ‘transition plans’ or in relation to more diffuse activities targeted at the transition. In either case, the metrics would apply within the same ‘boundaries’ – in terms of facilities, locations or other fields of action – as those plans and activities and their associated climate metrics.

The final set of just transition metrics should be one that can be embedded in sustainability reporting standards alongside important contextual information.

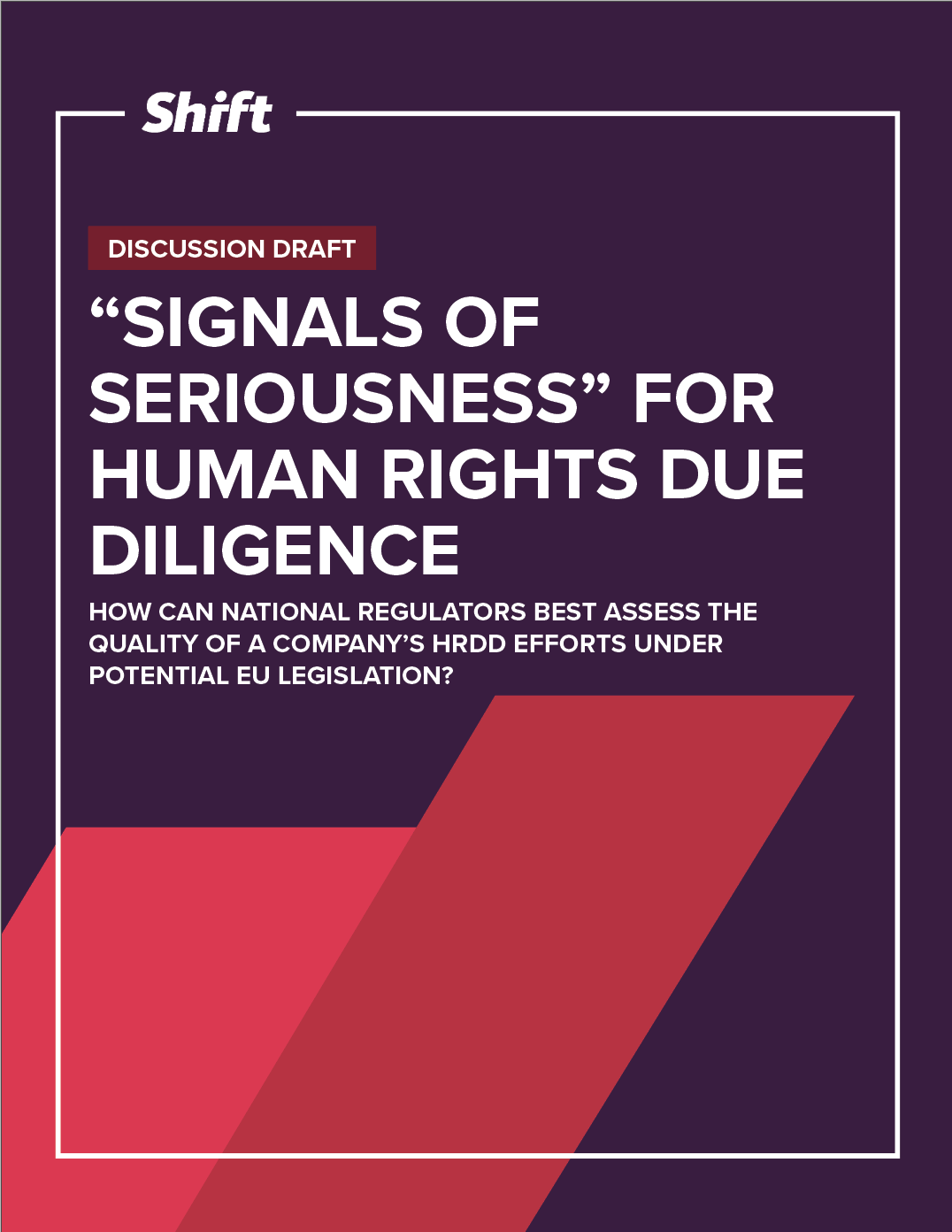

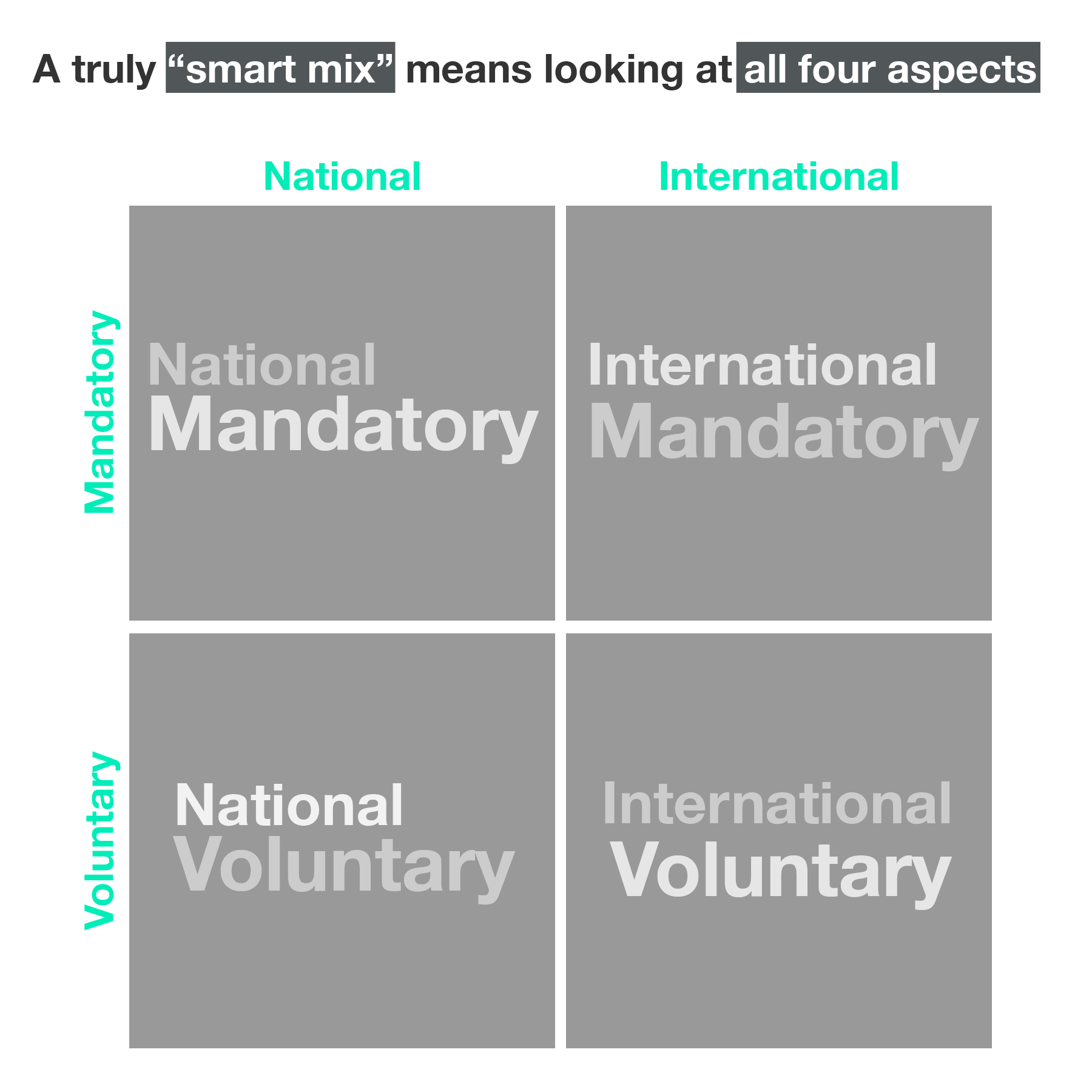

Figure 1 demonstrates how they might fit into the four-pillar structure that is common to many reporting standards today.

Figure 1

GOVERNANCE – High-level oversight of policy/strategy/transition planning – Human Rights Due Diligence process linked to transition planning and implementation – Approval of targets | STRATEGY – Just transition commitment – Decent jobs commitment – Social dialogue commitment – Identification of and meaningful engagement with affected stakeholders – Workforce composition |

| RISK AND IMPACT MANAGEMENT – Highest risk climate actions and locations – Measures taken to mitigate risks – Process for identifying and addressing skills gaps and opportunities | METRICS & TARGETS (this is our focus) – Job security Reskilling, upskilling and redeployment – Remuneration & living wage – Engagement with workers and communities |

We are sharing here an early draft – a work in progress – of a potential set of such metrics. They build on our experience working with the Global Reporting Initiative, which has made ground-breaking progress on just transition metrics as part of its 2025 revision of its Climate Change reporting standard. They also reflect inputs and suggestions from various organizations and ‘just transition’ experts. We are grateful to all those who have provided their insights to date.

We plan to continue and expand these conversations in the months ahead, as we know there is much that remains to be improved. Achieving a broad consensus around the current best-in-class metrics should bring clarity and value to all stakeholders: companies themselves as they try to measure what matters; data providers and investors who need this information for their own services and decisions; and reporting standard-setters needing to ensure consistency for preparers and insight for users of disclosed information.

We look forward to engaging with organizations interested in providing expertise and feedback to this effort, including organizations from the Global South. We welcome all inputs and advice as part of this continuing collaboration.