Also read: News announcement for this report | Our short framework for action on how any company can and should contribute to the SDGs

Update: In January 2017 the Business and Sustainable Development Commission, which commissioned this report, published its position paper on business’s role in sustainable development, Better Business, Better World. That position paper draws on this report and strongly supports its message that respect for human rights must be at the heart of any company’s efforts to contribute to the Sustainable Development Goals.

The summary below is excerpted from the report.

Summary

The United Nations Guiding Principles (UNGP) on Business and Human Rights set the global standard for what companies need to do to address negative impacts on people’s human rights connected with their business. The Guiding Principles look at how companies make their profits, not how they spend them. They are not a sign-up proposition, nor an optional extra, but an expectation of all companies everywhere and increasingly viewed as part of soft law.

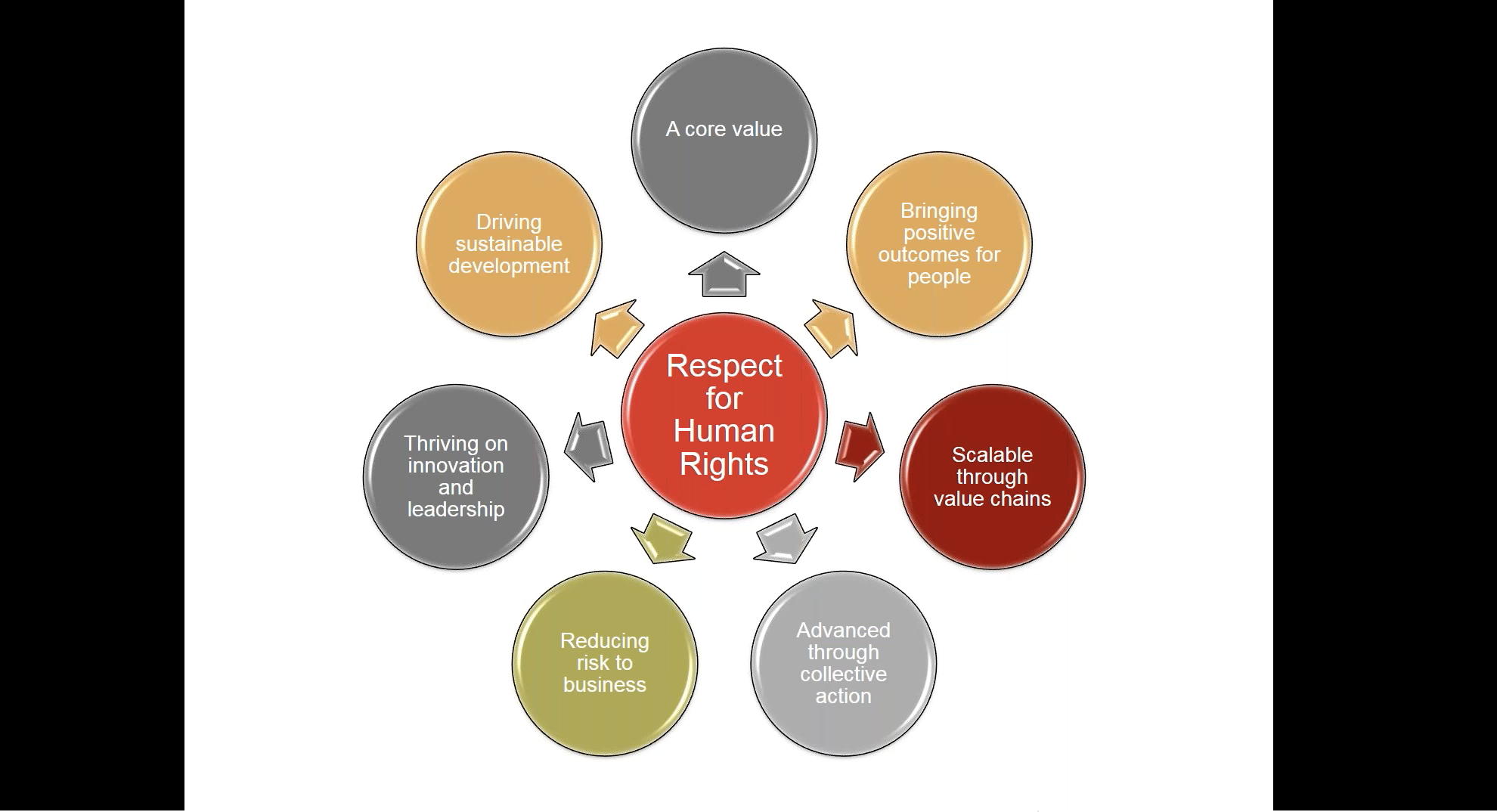

Yet the UN Guiding Principles are often cast as simply a ‘do no harm’ requirement, a matter of compliance or ‘just the starting point’ en route to more mature or innovative approaches to responsible business. This overlooks their tremendous potential to drive positive change for hundreds of millions of the poorest and most marginalised people in our societies – those least able to enjoy the fruits of development.

One of the most transformative aspects of the UN Guiding Principles is their recognition that a company’s responsibility to respect human rights is not just about what happens in their own operations where they largely control outcomes, but it extends also to human rights impacts connected to their products and services through their networks of business relationships. This often means creating and using leverage in those relationships to bring about greater respect for human rights. For many human rights challenges – particularly those that sit in global value chains – that means collaborating to drive change. This is the key to how business can, and should, make its largest positive contributions to the ‘people part’ of sustainable development.

This paper makes the case for the Business and Sustainable Development Commission (BSDC) to take a lead in changing the current outdated discourse on business and social development, by recognising and harnessing this unique potential of the UNGPs. First it reviews some statistical evidence of the scale of populations across global supply chains that are exposed to abuses of their human rights. It then reviews the evidence of the strong and growing convergence between these severe risks to people and risks to business itself – operational, financial, reputational, legal or in staff recruitment and retention. The subsequent sections explore the increasing attention of international leaders – including in the G7, International Labour Organization (ILO), European Union (EU) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) – to human rights risks in global value chains and to the role that implementation of the UNGPs must play if we are to accelerate change. Following a brief review of the UNGPs, the paper explores the evolution in initiatives that use collective leverage to advance respect for human rights. It highlights a new generation of such initiatives in the form of “joint action and accountability platforms”, which focus on specific human rights challenges, involve the key agents of change in setting action-oriented targets that address the issues holistically and incorporate accountability for progress in meeting them.

The final sections of this paper explore why the current discourse on the role of business in social development has skipped over the tremendous scale of positive impacts to be achieved through advancing respect for human rights. They look back at the historical focus on philanthropy and social investment and the more recent preoccupation with new business innovations and models such as “shared value”. The paper argues that while these approaches can bring hugely valuable benefits to societies as well as the companies concerned, they will always remain constrained to certain market opportunities and policy environments.

The paper concludes that the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) present an opportunity not just to update our vision of the role of business in sustainable development, but to change it fundamentally. There is no more pressing or more powerful way for business to accelerate social development than by driving respect for human rights across their value chains. The proposition that all companies not only can contribute at scale to development through these networks of business relationships, but that they have a responsibility to do so, is the quiet revolution that sits at the heart of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. The paper closes with a set of specific recommendations about how to embed this vision at the heart of how business gets done.