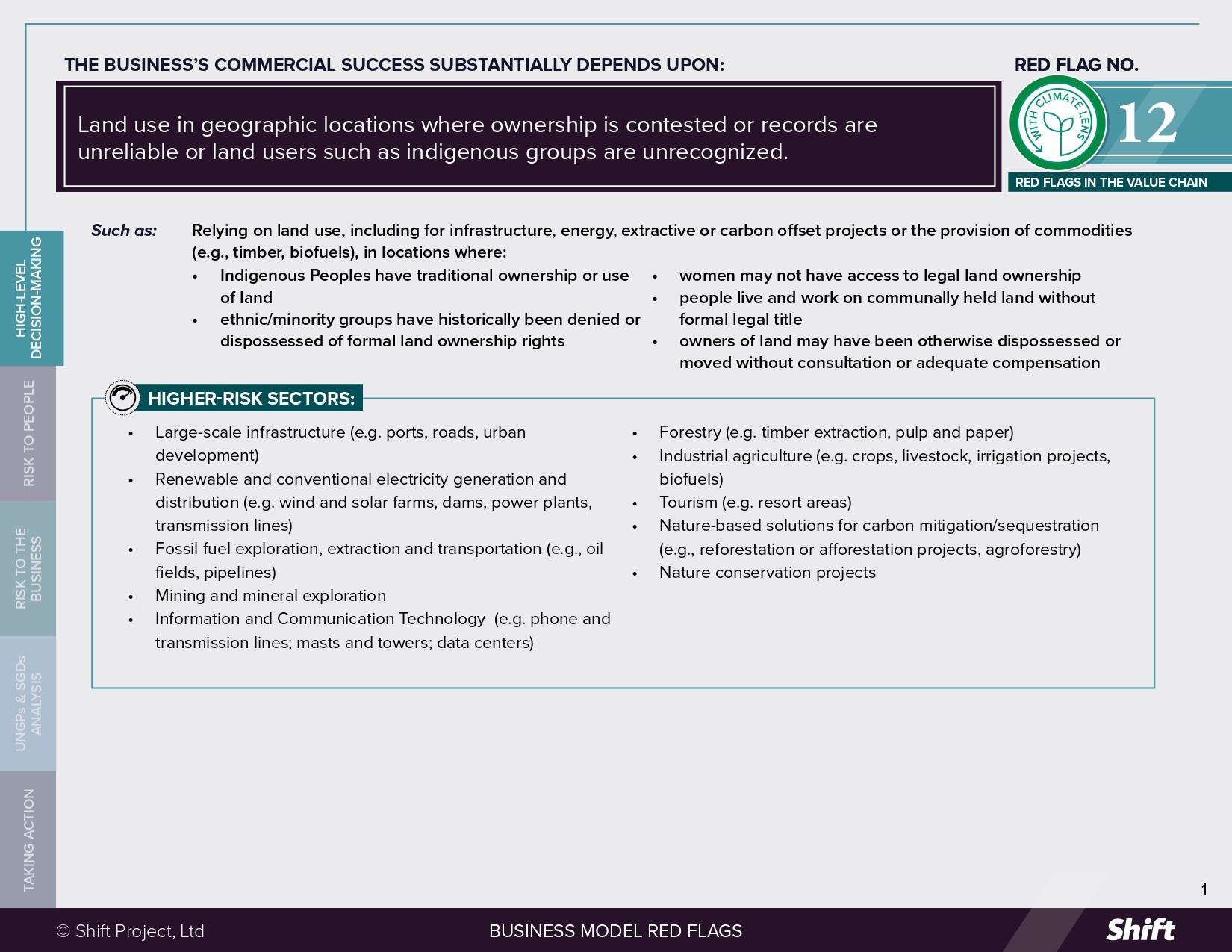

RED FLAG # 12

Land use in geographic locations where ownership is contested or records are unreliable or land users such as indigenous groups are unrecognized.

For Example

Relying on land use, including for infrastructure, energy, extractive or carbon offset projects or the provision of commodities (e.g., timber, biofuels), in locations where:

- Indigenous Peoples have traditional ownership or use of land

- Ethnic/minority groups have historically been denied or dispossessed of formal land ownership rights

- Women may not have access to legal land ownership

- People live and work on communally held land without formal legal title

- Owners of land may have been otherwise dispossessed or moved without consultation or adequate compensation

Higher-Risk Sectors

- Large-scale infrastructure (e.g., ports, roads, urban development)

- Renewable and conventional electricity generation and distribution (e.g., wind and solar farms, dams, power plants, transmission lines)

- Fossil fuel exploration, extraction and transportation (e.g., oil fields, pipelines)

- Mining and mineral exploration

- Information and Communication Technology (e.g., phone and transmission lines; masts and towers; data centers)

- Forestry (e.g., timber extraction, pulp and paper)

- Industrial agriculture (e.g., crops, livestock, irrigation projects, biofuels)

- Tourism (e.g., resort areas)

- Nature-based solutions for carbon mitigation/sequestration (e.g., reforestation or afforestation projects, agroforestry)

- Nature conservation projects

Questions for Leaders

- How does the company confirm that the land acquisitions or use rights granted in higher-risk geographies do not in fact infringe legal or traditional ownership or use rights?

- Are there existing agreements with Indigenous Peoples and, if so, how does the company know whether these agreements are based on free, prior and informed consent and fair and equitable benefit sharing?

- How does the company ensure that it does not participate in or benefit from improper forced relocations, and adequately compensates inhabitants in voluntary relocations?

- How does the company ensure that potentially impacted communities have access to safe and effective ways to raise land-related concerns with the company?

- What specific actions does your company take to ensure that land used in your operations is restored to an equivalent or improved condition after use? How are you planning to finance such actions?

How to use this resource. ( Click on the “+” sign to expand each section. You can use the side menu to return to the full list of red flags, download this Red Flag as a PDF or share this resource. )

Understanding Risks and Opportunities

Risks to People

-

As stated by the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), “[l]and is not a mere commodity, but an essential element for the realization of many human rights”. As a source of livelihood and a strong element of the identities of Indigenous Peoples, pastoralists, campesinos and other local communities, land is a fundamental aspect of economic, social and cultural rights. The rights of smallholder farmers are also impacted in locations where land use is contested, as competing interests from governments, corporations, and conservation projects can lead to displacement or restricted access. In such contexts, weak land tenure systems and lack of formal recognition of customary land rights leave smallholders especially vulnerable. This has implications not only for farmers’ livelihoods and food security but also broader sustainable development objectives, such as environmental stewardship.

-

Companies can be involved with negative impacts where they acquire land rights in locations in which rights to land are contested, relying on assurances from sellers or lessors, whether governments or private individuals, without further due diligence to identify whether competing claims exist.

-

Human Rights Watch released a detailed report documenting illegal land confiscation from farmers in Myanmar, some of which was sold to companies.

-

-

The transition toward a low carbon economy is expanding the range of businesses that carry this business model risk.

-

This is exemplified by the renewable energy value chain, wherein there is not only a voracious appetite for land to develop low carbon energy projects (e.g., wind and solar farms or biofuel processing facilities) there is also increasing demand for land-derived inputs for these low carbon technologies, such as critical minerals or biomass. One study found that the demand for transition minerals is so great that severe shortages are anticipated for several of them by 2100. Given that Indigenous Peoples manage an estimated 20% or more of the Earth’s land surface and over 50% of transition minerals needed for the energy transition are located on or near Indigenous territories, these demands for land across the renewable energy value chain are putting further pressure on the rights of Indigenous Peoples, as well as other vulnerable communities.

-

National and corporate net zero commitments are also driving demand for land-based carbon sequestration and mitigation projects (“nature-based solutions”) to supply global carbon markets with carbon credits. While such projects are, in principle, undertaken to support positive climate outcomes, the environmental and social safeguards underpinning such projects vary widely. Almost all carbon credit methodologies, standards and certification schemes lack rigorous human rights due diligence and, as a result, can lead to real and acute harms to people. For example, a “REDD+” carbon offsetting project in Cambodia has recently been accused of violating the rights of Indigenous communities by excluding them from decision-making, restricting access to ancestral lands, disrupting livelihoods and failing to uphold protections for Indigenous land tenure and cultural rights.

-

-

The physical impacts of climate change, including increased drought, flooding, and extreme heat, can magnify the risks associated with this business model feature by intensifying competition over scarce resources, accelerating land degradation, and triggering displacement of vulnerable communities. Further, insecure tenure rights limit the ability of these communities to invest in adaptive measures such as soil restoration, water management, or agroforestry, leaving them less able to withstand climate shocks and compounding the impacts on people resulting from this business model feature.

-

Impacts on land rights, including those arising from corporate activities, affect people differently, with disproportionately negative effects on individuals and groups who are traditionally discriminated against and marginalized, including women, indigenous peoples, rural communities and small-scale farmers. Where tenure is insecure, business activities can inadvertently cause these groups to lose rights to lands and resources, triggering a range of negative social impacts.

-

Rural poor: In low- and middle-income countries, up to 28 per cent of people have limited access to land or don’t have security of tenure. For the rural poor, access to land is the most critical way to make a living. Farming lands, forests, water and fisheries are essential resources for the enjoyment of their right to an adequate standard of living, including the right to adequate food and nutrition, water, and sanitation. Many rural poor people access land and other natural resources under informal systems with limited systematically documented rights, which leaves them vulnerable to dispossession by those who are more powerful.

-

Indigenous Peoples: Indigenous Peoples have specific human rights to own, use, develop and control the lands, territories and resources that they possess by reason of traditional ownership or other traditional occupation or use, as well as those which they have otherwise acquired. In line with their land-related human rights, set out in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, any project that affects their territories and resources should only be undertaken with their Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC). The lack of recognition of indigenous peoples and of their land rights, and differing interpretations of what actions and evidence are needed to demonstrate FPIC have led to the dispossession and forced evictions of Indigenous Peoples from their ancestral lands, as well as associated impacts to their cultural heritage and traditional practices. Indigenous Peoples’ representatives have highlighted “the increasing trend of criminalization and attacks against Indigenous Peoples Human Rights Defenders”, including in the context of the low carbon transition.

-

Women: Women also face severe challenges regarding access, use and ownership over land and its resources in many regions, with statistics showing that women consistently own less land than men, regardless of how ownership is conceptualized. Discrimination in inheritance, and/or the lack of proper land tenure and control can affect women’s livelihoods, food security, economic independence and physical security, making them more vulnerable to poverty, hunger, gender-based violence and displacement.

-

Ethnic minorities are disproportionately affected by low access to and ownership of land, often because of wider societal discrimination. ‘Land grabbing’ is compounding the vulnerability of minorities.

-

-

Land-related conflicts are getting more violent. Between 2012 and 2023, more than 2100 people, including both Indigenous and non-Indigenous human rights defenders, have been killed or disappeared for standing up to protect their homes and lands, with almost 40% of those cases linked to mining & extractives, agribusiness, logging and hydropower.

Risks to the Business

|

What the UN guiding principles say

A company may cause impacts where it fails to conduct resettlement processes in line with human rights standards and due process, including the use of excessive force to remove people from land it has acquired. It could also cause negative impacts on people’s human rights where it fails to provide adequate remedy for any damage to land, property, water access and quality, or land-based livelihoods resulting from its activities.

A company may contribute to negative impacts where it acquires land from a State or a third party in circumstances in which it is, or should be, aware that there may be competing claims to the land and does not conduct proper due diligence to investigate land ownership and consult with affected groups. It may also contribute to impacts where it makes it more difficult or impossible for the rightful owners to access and benefit from the acquired land.

Companies downstream of land usage in their supply chain may be linked to land-related impacts by way of their products or services. For example, a company in the food and beverage industry that purchases agricultural commodities through a food processing company, or directly from a sugar grower or other agricultural company, may be linked to land related abuses occurring at source. Moreover, linkage may occur when a company acquires or uses disputed land despite having taken reasonable measures to verify that the land titles were fully legitimate and not the result of dispossession or any other type of denial of ownership by rightful communities.

In cases of linkage, once the company becomes aware of the claims, it may move into a situation of contribution over time if it takes no action to investigate and/or address the impact.

Possible Contributions to the SDGs

|

According to the Voluntary Guidelines on the Governance of Tenure, published by the UN FAO, securing land tenure rights and ensuring responsible land governance is key to achieving the SDGs. Addressing impacts on people associated with this red flag can contribute to, among other things: SDG 1.4 End poverty in all its forms everywhere By 2030, ensure that all men and women, in particular the poor and the vulnerable, have equal rights to economic resources, as well as access to basic services, ownership and control over land and other forms of property, inheritance, natural resources, appropriate new technology and financial services, including microfinance Indicator 1.4.2 Proportion of total adult population with secure tenure rights to land, with legally recognized documentation and who perceive their rights to land as secure, by sex and by type of tenure

SDG 2.3 End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture By 2030, double the agricultural productivity and incomes of small-scale food producers, in particular women, indigenous peoples, family farmers, pastoralists and fishers, including through secure and equal access to land, other productive resources and inputs, knowledge, financial services, markets and opportunities for value addition and non-farm employment

SDG 5.a Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls Undertake reforms to give women equal rights to economic resources, as well as access to ownership and control over land and other forms of property, financial services, inheritance and natural resources, in accordance with national laws Indicator 5.a.1.(a) Proportion of total agricultural population with ownership or secure rights over agricultural land, by sex; (b) Share of women among owners or rights-bearers of agricultural land, by type of tenure. Indicator 5.a.2. Proportion of countries where the legal framework (including customary law) guarantees women’s equal rights to land ownership and/or control.

SDG 7. Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all Indicator 7.2 By 2030, increase substantially the share of renewable energy in the global energy mix |

Taking Action

Due Diligence Lines of Inquiry

Due Diligence Lines of Inquiry adapted from the Danish Institute for Human Rights’ Human Rights Compliance Assessment Quick Check.

-

Are the State policies and laws that ensure tenure rights non-discriminatory and gender sensitive? Does the State ensure equal tenure rights for women and men, including the right to inherit and pass on these rights?

-

Does the State recognize as indigenous any groups that claim indigenous status, and does it recognize Indigenous People’s rights with regard to land, as set out in the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples?

-

Before purchasing land, did we investigate all existing claims and conflicts and consult with all affected parties, including both legal and customary owners, and if Indigenous Peoples are involved, did we obtain their free, prior and informed consent and have we come to any agreements around fair and equitable benefit-sharing?

-

Considering that government maps do not always accurately reflect the traditional land usage of Indigenous Peoples, are we verifying this information, such as with the help of a person with deep expertise in and understanding of indigenous cultures and local tenure arrangements?

-

Do we understand the way in which the land may be used by other local, non-Indigenous, communities and the potential implications that our proposed land-use may have on those communities? Do we have a process by which to arrive at benefit-sharing agreements with these non-Indigenous communities?

-

When purchasing or leasing property from governments or large-scale landowners, did we investigate past occupation of the land to ensure that no forced relocations had been performed, unless done in conformity with international standards?

-

Do we conduct due diligence with regard to the ownership and usage of land from which we derive key commodities or services through our supply chain, where such land is in regions with weak protections for traditional land rights or a history of land-related conflicts?

-

Do we ensure that we do not participate in or benefit from improper forced relocations, and that we adequately compensate inhabitants involved in voluntary relocations?

-

Does the company honor the rights of local or Indigenous Peoples on company-controlled land?

-

Are our employees and security personnel trained to interact appropriately with indigenous and other local communities, allowing safe and unimpeded use of the land and its resources without harassment or intimidation?

-

Do we have on-going processes in place to engage with local communities in order to understand any land-related impacts that may arise from our activities? Are we confident that local communities – women as well as men – feel able to raise issues with the company as part of those dialogues?

-

Have we considered women’s uses of land? Have women been involved in any decision-making processes about how land will be used and appropriate mitigation measures?

-

Does the company have a broader community engagement or Indigenous Peoples policy and process, which includes the principle of Free, Prior and Informed Consent?

-

Do we have processes in place to integrate issues raised by communities into company decision-making in a timely fashion?

-

Have we committed sufficient internal resources, capacity and time towards implementing strong policies on respecting rights of Indigenous Peoples and implementation of free, prior and informed consent?

-

Does the State provide access to impartial and competent judicial and administrative bodies to resolve disputes over tenure rights, including effective remedies where appropriate?

-

Do we have mechanisms for hearing, processing, and settling any grievances of local communities? How confident are we that communities trust those mechanisms and feel able to use them in practice?

-

To what extent have we developed a plan for how we might decommission our project at end-of-life? Is this plan adequately financed and has it been consulted with potentially affected stakeholders or their proxies?

Mitigation Examples

|

* Mitigation examples are current or historical examples for reference, but do not offer insight into their relative maturity or effectiveness.

|

Alternative Models

|

Other Tools and resources

Guidance for Companies

-

Landesa Business Enterprise Supporting Materials: https://ripl.landesa.org/support/1

-

Landscope (a system for measuring tenure risk) https://landportal.org/library/resources/landscope

-

Shift, The Human Rights Opportunity: Land Rights, https://www.shiftproject.org/sdgs/land-rights/

-

Exploring Shared Prosperity: Indigenous leadership and partnerships for a just transition (2024),

-

Indigenous Peoples Major Group, with contributions from the Danish Institute for Human Rights (2018) Doing it right! Sustainable energy and indigenous peoples

-

Human Rights and Biodiversity Working Group (2022) A rights-based path for people and planet

-

UN Global Compact (2013) Business Guide to the UNDRIP

-

UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), Respecting Free, Prior and Informed Consent: Practical Guidance for Governments, Companies, NGOs, Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities in Relation to Land Acquisition, Governance of Tenure Technical Guide No. 3 (2014),

-

First Nations Major Projects Coalition – Tools & Resources

-

First Nations Clean Energy Network (2023) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Best Practice Principles for Clean Energy Projects

-

World Economic Forum (2023) Using a People-positive Approach to Accelerate the Scale-up of Clean Power – A C-Suite Guide for Community Engagement (White Paper)

Key Standards

-

IFC (2012) Performance Standard 5, Land Acquisition and Involuntary Resettlement,

-

UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, “Basic Principles and Guidelines on Development Based Evictions and Displacements,” (Annex 1 of the report of the Special Rapporteur on adequate housing as a component of the right to an adequate standard of living).

-

UN OHCHR (2015) Land and Human Rights: Standards and Applications, HR/PUB/15/5/Add.1,

Other Useful Materials

-

Global Reporting Initiative (2016) Land Tenure Rights,

-

Danish Institute for Human Rights (2024) Human Rights Land Navigator

-

Measuring global perceptions of land and property rights (2024), https://www.prindex.net

-

International Land Coalition (2024) A Land Use and Tenure Indicator to Protect Traditional Knowledge

-

ODI and TMP Systems (2019) QTR Tenure Risk Tool

-

Realizing Women’s Rights to Land and Other Productive Resources , https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Publications/RealizingWomensRightstoLand_2ndedition.pdf

-

LandLinks, Fact Sheet: Land Tenure and Women’s Empowerment, https://www.land-links.org/issue-brief/fact-sheet-land-tenure-womens-empowerment/

-

Securing Women’s Land Rights for Increased Gender Equality, Food Security and Economic Empowerment, UN Chronicle (2023) https://www.un.org/en/un-chronicle/securing-women’s-land-rights-increased-gender-equality-food-security-and-economic

-

Rights and Resources Initiative, Who Owns the Land? – A global baseline of formally recognized indigenous and community land rights (2015), https://rightsandresources.org/wp-content/uploads/GlobalBaseline_web.pdf

Citation of research papers and other resources does not constitute an endorsement by Shift of their conclusions.

Business Model Red Flags

Business Model Red Flags  Tool for Indicator Design

Tool for Indicator Design