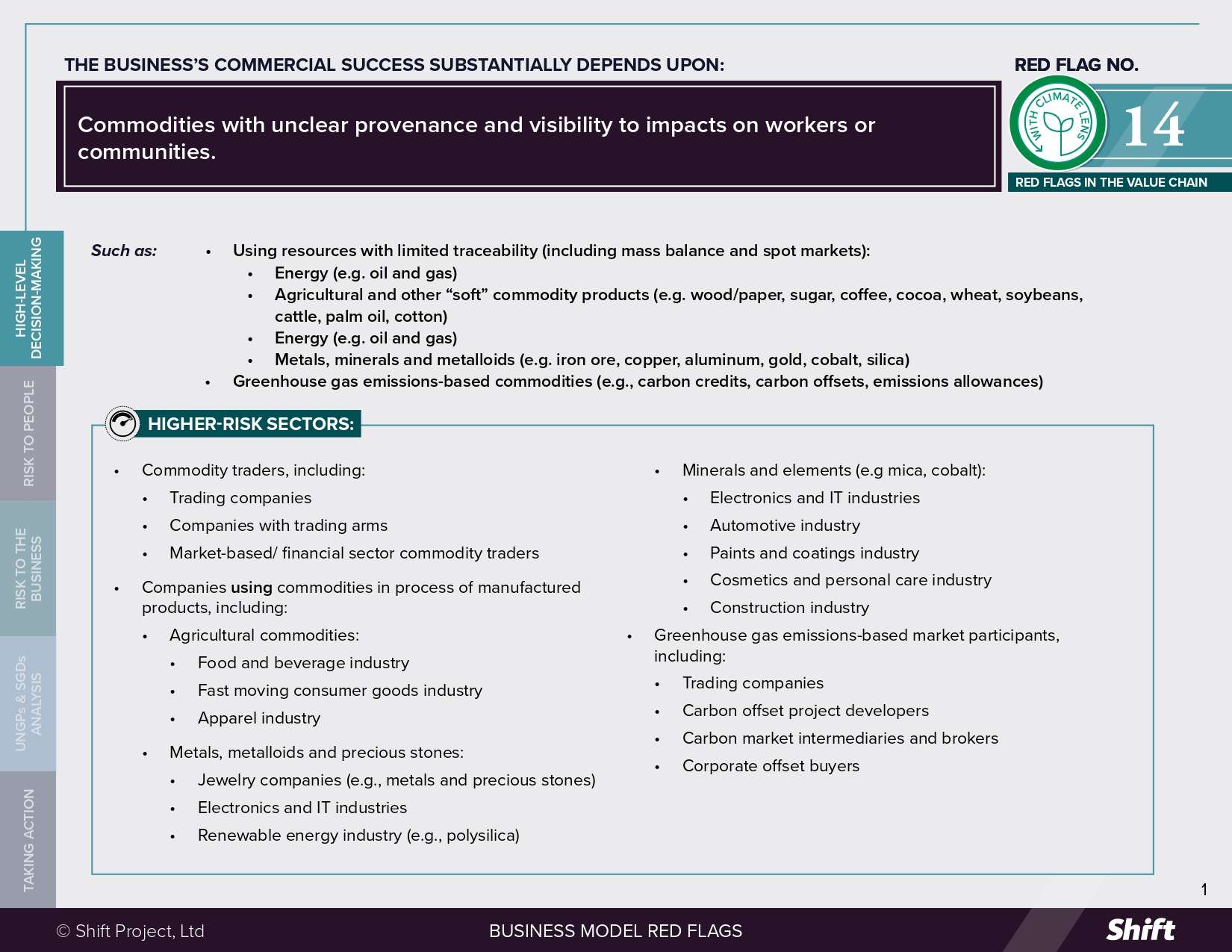

RED FLAG # 14

The business’s commercial success substantially depends upon commodities with unclear provenance and visibility into impacts on workers or communities.

For Example

- Using resources with limited traceability (including mass balance and spot markets):

- Agricultural and other “soft” commodity products (e.g., wood/paper, sugar, coffee, cocoa, wheat, soybeans, cattle, palm oil, cotton)

- Energy (e.g., oil and gas)

- Metals, minerals and metalloids (e.g., iron ore, copper, aluminum, gold, cobalt, silica)

Higher-Risk Sectors

- Commodity traders, including:

- Trading companies

- Companies with trading arms

- Market-based/ financial sector commodity traders

- Companies using commodities in the process of manufactured products, including:

- Agricultural commodities:

- Food and beverage industry

- Fast-moving consumer goods industry

- Apparel industry

- Metals, metalloids and precious stones:

- Jewelry companies (e.g., metals and precious stones)

- Electronics and IT industries

- Renewable energy industry (e.g., polysilica)

- Minerals and elements (e.g., mica, cobalt):

- Electronics and IT industries

- Automotive industry

- Paints and coatings industry

- Cosmetics and personal care industry

- Construction industry

- Agricultural commodities:

- Greenhouse gas emissions-based market participants, including:

- Trading companies

- Carbon offset project developers

- Carbon market intermediaries and brokers

- Corporate offset buyers

Questions for leaders

- What effort has the company made to understand the sources of its key inputs/ingredients and the environmental or socially-related risks/issues that arise in the value chain?

- How does the company find out about human rights risks associated with the commodities on which it relies? Does it do so at the stage of product design or sourcing? What does it do to address the risks it finds?

- What is the company’s view on building longer-term sourcing commitments for the commodities on which it relies in order to make them more traceable?

- How is climate change (water scarcity, temperature increases, extreme weather events) affecting the people where the commodity is sourced, processed or distributed?

- To what extent does the company’s value proposition rely on the price of an agricultural commodity being depressed below levels deemed sufficient to sustain living incomes/ wages? Does the business model rely on substantial market power to drive down pricing? (See further Red Flag 19).

How to use this resource. ( Click on the “+” sign to expand each section. You can use the side menu to return to the full list of red flags, download this Red Flag as a PDF or share this resource. )

Understanding Risks and Opportunities

Risks to People

- IHRB notes that a wide range of agricultural and mined commodities can be associated with adverse human rights impacts “at the point of production or extraction”, including impacts on:

- Workers: Such as unfair, unsafe or unhealthy working conditions, child and forced labor, as well as exploitation and/or discrimination of migrant workers. Where lowest cost is the largest business driver (e.g. in the commodities market), farmers, stockbreeders, fishermen and smallholders have limited influence in negotiating terms of trade and receive an ever-diminishing share of the fruits of their labor. (See further Red Flags 1 and 19).

- Communities: Such as activities taking place in the absence of adequate community consent, resettlement of indigenous communities without Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC), public/private security forces infringing on workers’, Indigenous Peoples’, and communities’ rights.”

- Where commodities of unknown provenance are bought, sold, traded and hedged, it becomes difficult for companies upstream in the value chain to understand where the materials came from or under what conditions they were produced, and therefore to influence these decisions so as to address potential negative impacts on the rights of people in the value chain.

- The physical impacts of climate change, already being felt in certain regions, are expected to further intensify the impacts on people in the value chain. A recent report by PWC, details how extreme heat and prolonged drought are expected to disrupt major commodity supply chains—for example, by 2050 over 70% of cobalt and lithium production will be impacted—due to concentrated sourcing patterns in particular regions. These conditions not only threaten yield and extraction costs—they are also anticipated to drive down worker productivity and directly endanger the health, safety, and livelihoods of miners and farmworkers.

- In parallel, the global transition to a low carbon economy and the digital transformation are increasing demand for a number of commodities that have been linked to severe human rights risks and impacts. The extraction, processing and, in some cases, transportation of key minerals used in clean energy and information technology applications have been linked to issues such as child labour, forced labour, land grabbing, deforestation and environmental pollution. Reports indicate that companies accounting for 75 percent of the global battery market have connections to one or more supply chain companies facing allegations of severe human rights abuses. This is a worrying trend, particularly when coupled with projections for dramatically increasing demand for such commodities. The International Energy Agency has predicted that mineral demand for clean energy applications alone is set to grow by three and a half times by 2030 on the pathway to reaching global net zero emissions by 2050.

- In response to net zero emissions commitments, demand has increased for greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions-based commodities, notably carbon credits. These commodities represent GHG emissions that were avoided, reduced or removed, for example through projects that prevent deforestation or plant trees. Governments, companies, and individuals may purchase these credits to compensate for, or “offset,” their emissions elsewhere. However, human rights due diligence on projects generating carbon credits is often inconsistent—many schemes fall short on meaningful community consultation, land rights protections, and equitable benefit-sharing. As a result, some of the underlying projects from which market-based carbon commodities are sourced have been linked to human rights violations.

- Some examples of risks to people associated with this business model include:

- Child Labor: Research by Impact details the pervasiveness of child labor throughout the artisanal cobalt mining sector in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). For example, mica mining, particularly in illegal small-scale artisanal mines, has been associated with child labor. Over 22,000 child laborers have been identified across only two geographic areas in India (which cover less than half the so-called “mica mining belt”).

- Forced Labor: Research across multiple organizations has explored how the textile/apparel, agricultural and renewable energy sectors have pervasive connections to forced labor in China’s Uyghur Region, with implications across international commodities markets associated with these sectors, including for cotton, tomatoes and polysilicon (used for solar panels). A recent study by Global Rights Compliance has detailed how China’s expansion of critical mineral exploration, mining, process and manufacturing in Xinjiang region is a critical risk for companies across multiple sectors – from electronics to aerospace to energy.

- Land grabbing and forced evictions: In the DRC, Amnesty International has documented multiple cases of forced evictions of entire communities as companies seek to expand industrial-scale cobalt and copper mining projects in response to the growing demand for these commodities for use in rechargeable batteries.

- Violation of free, prior and informed consent: In Cambodia, a two-year investigation by Human Rights Watch of Cambodia’s Southern Cardamon REDD+ carbon crediting project revealed widespread mistreatment of the Chong people, as well as extended project-related activities in the absence of consent of impacted Chong communities.

- Deforestation and environmental pollution: In Indonesia, the world’s largest producer of nickel (a critical input to renewable energy and electric vehicle batteries), Climate Rights International found that there has been extensive deforestation and water pollution as part of the nickel industry’s recent expansion there, resulting in severe impacts for the livelihoods of local communities.

Risks to The Business

- Business, Reputational, Operational, Regulatory and Legal Risks: Commodity markets are synonymous with extreme price pressure on farmers and other workers at source, which can undermine availability of product and stability of supply. The company also risks being involved in business relationships with disreputable organizations or individuals, including groups using forced or child labor or operating unsafe working environments, or may be financially supporting conflict. Operational challenges, reputational damage and even legal risks can arise where such connections come to light and the business must act reactively to exclude such sources from their value chain. Where traceability to individual companies is limited, entire industries can face civil society pressure to improve (e.g. in the case of palm oil).

-

The US Government enacted the Uyghur Force Labor Prevention Act in 2021, which prevents the entry of products made with forced labor into the United States by investigating and acting upon allegations of forced labor in supply chains. Thousands of shipments from the electronics, apparel, footwear, pharmaceutical, agricultural, industrial, and automotive sectors have been reviewed for connections to forced labor, resulting in goods “totaling hundreds of millions of US dollars” being denied entry at the US border.

-

In 2023 the Amsterdam City Council decided to ban Colombian coal from the Port of Amsterdam in response to reports and complaints that this “blood coal” was associated with serious human rights violations. Relatedly, in August 2025, the Dutch National Contact Point formally accepted a complaint by Colombian farming communities, supported by PAX and SOMO, against HES International and the port authorities of Rotterdam and Amsterdam for their involvement in transporting “blood coal” linked to forced displacement of over 59,000 people in a northern mining region of Colombia.

-

In 2022, Peruvian indigenous leaders filed a case with the Dutch National Contact Point against the Louis Dreyfus Company B.V. (LDC) arguing that despite abundant public information concerning grave environmental and human rights impacts, LDC continued to purchase crude palm oil from the Ocho Sur Group whose oil palm plantations are involved in the illegal deforestation of over 12,000 ha of Amazon virgin forest, human rights violations of the Indigenous Community of Santa Clara de Uchunya and the Shipibo-Konibo people and corruption schemes for land grabbing.

-

A Global Witness report found that several major international brands were sourcing palm oil from Brazilian plantations linked to violence, torture and land fraud. Based on mill lists or on public information available on trade data systems, Global Witness identifies 20 companies, including Danone, Ferrero, Bunge, Hershey, Kellogg, Nestlé and Pepsico, with direct or indirect links to human rights abuses.

-

In December 2021, the non-profit organization Public Eye released research alleging that Swiss-based commodity traders, together owning over 550 plantations of various agricultural commodities across the world on at least 2.7 million hectares, fail to take sufficient responsibility for human rights and environmental abuses on their land holdings, including evictions, labor abuse, and deforestation. Their interactive platform names several agricultural traders, including Archer Daniels Midland, Bunge, Cargill, Chiquita, LDC, Neumann Kaffee Gruppe and Viterra.

-

In 2023, the Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations (SOMO), published a report documenting allegations of sexual abuse, harassment and exploitation linked to the Kasigau Corridor conservation project in southern Kenya, operated by the California-based firm Wildlife Works. This project is the source of “carbon offsets” purchased by companies such as Shell and Netflix.

- The Dutch National Contact Point for the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises (NCP) received a complaint from a consortium of 22 Italian associations and NGOs in 2022 alleging violation of the OECD Guidelines by Stallantis N.V. and FCA Italy S.p.A and requesting the disclosure of detailed information on their suppliers’ operations at cobalt and other minerals mining sites in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The complaint, which represents one of the first focused on a company’s mineral supply chain, was accepted by the Dutch NCP (after being deferred by the Italian NCP) and is pending decision.

- Regulatory Risk: The EU’s deforestation regulation, currently scheduled to come into effect from 30 December 2025 (and June 2026 for smaller companies) requires companies to prove key agricultural commodities (e.g., soy, palm oil, coffee, cocoa) coming into the EU have deforestation-free origins. The regulation also includes provisions around violations of nationally applicable laws that relate to land rights, environmental protection, labor rights, and free, prior and informed consent.

- Business Opportunity: Focusing on improved livelihoods for people within the supply chain helps to build more resilient corporate supply chains. Opportunities for price reduction and new sources can be unlocked:

Barry Parkin, Chief Procurement and Sustainability Officer of Mars, has noted that supply chains are “broken.” In a 2018 article arguing that the “commodity era is over,” he identifies win-win opportunities to “move beyond commodities that are bought and sold in markets where the lowest cost is the largest business driver. Instead, we must shift to long-term models for corporate buying that are anchored on building mutuality, reliability, resilience and risk management into the core of our buying patterns.”

What the UN guiding principles say

*For an explanation of how companies can be involved in human rights impacts, and their related responsibilities, see here.

- Companies risk being directly linked to human rights impacts as a result of harmful practices associated with the commodities going into their products.

- Where companies ought to be aware of risks associated with commodities incorporated in their products, including, for example, where a commodity is overwhelmingly sourced from one location where it is associated with human rights impacts, the company may be contributing to impacts if it fails to use its leverage to try to address the impacts, either alone, or in collaboration with others.

Possible Contrubutions to the SDGs

Addressing impacts on people associated with this red flag indicator can contribute to a variety of SDGs, depending on the impacts associated with the commodities. This may include, for example:

- SDG 1: Eradication of poverty in all its forms.

- SDG8:Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all, in particular:

- Target 8.7 Eradication of forced labor, modern slavery and human trafficking, securing the prohibition and elimination of the worst forms of child labor, including the recruitment and use of child soldiers, and ending child labor in all its forms by 2025.

- SDG 10: Reduce inequality within and among countries.

- SDG 12: Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns, in particular:

- Target 12.6 Encourage companies, especially large and transnational companies, to adopt sustainable practices and to integrate sustainability information into their reporting cycle.

- SDG 16: Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels, in particular:

- Target 16.2 End abuse, exploitation, trafficking, and all forms of violence against and torture of children.

Taking Action

Due Diligence Lines of Inquiry

Risk Identification and assessment

- What opportunities exist to build greater visibility into our direct and indirect sourcing relationships?

- Which commodities that we use may be of higher risk from a human rights perspective, based on known information about potential source countries?

- How might the company’s actions to address its climate-related risks and opportunities change its reliance on certain commodities? How does the company determine the human rights risks associated with those changes? How has the company factored such considerations into its overall approach to its climate change mitigation and adaptation planning and implementation?

- How have environmental, social and human rights-related safeguards been built into the process of sourcing carbon-based commodities?

- Where information about impacts associated with the commodity is scant, how can we learn from known information about human rights impacts associated with other commodities sourced from the same area?

- Which partnerships, including with peers, international organizations, academics or NGOs, can we leverage to gain greater transparency or ensure traceability? Where no initiatives exist, can we create one?

Taking action

- What leverage do we have with our direct suppliers, traders and processors to address risks and impacts?

- How can we increase our leverage e.g., through contractual clauses, commercial conversations, expertise, joint capacity building, etc?

- Have we considered whether and how we can reduce our reliance on commodities markets and increase our engagement, visibility and leverage with the producers of the raw materials on which our business relies? Have we considered available examples from other companies to articulate the longer-term business benefits of this approach?

Mitigation Examples

Transparency, shortening of supply chains and longer-term commitments from buyers can “demystify complex supply chains,” and allow “different actors [to] identify and minimize risks and improve conditions on the ground and inform whether and where progress is being made.”

- The Child Labour Platform, a multistakeholder initiative, aims to convene stakeholders to address the root cases of child labor in the agricultural and mining sectors – with a focus on cocoa and cobalt – through initiatives aimed at prevention, assessment and remediation, provision of guidance to improve company practice, as well as to develop innovative collaboration models.

- In September 2024, the Solar Energy Industry Association sought public comments on their draft solar supply chain traceability standard which is the first of its kind and details how to conduct forced labor-focused due diligence, including building a traceability system to trace the provenance of materials from upstream suppliers. As of September 2025, the updated standard is still awaiting final publication.

- In 2018, the BMW Group and Codelco, a Chilean copper mining company, signed an agreement to cooperate on a sustainable and transparent supply of copper. In the “decommoditized” copper market, prices reflect differences in levels of certification.

- Many large consumer goods companies are disclosing the source of their palm oil through the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, including Unilever, which, in 2018 announced that it was “the first consumer goods company to publicly disclose the palm oil suppliers and mills it sources from” (both directly and indirectly), and Nestle, which reported that by the end of 2023, 96% of its palm oil supply was deforestation-free and has implemented satellite monitoring systems to detect and address deforestation risks. The Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) maintains a “Shared Responsibility” framework, requiring members to incrementally increase their uptake of certified sustainable palm oil, with specific targets set for different member categories. In 2024, the RSPO introduced a verification manual and sanction mechanisms to ensure compliance with these commitments.

-

The Global Battery Alliance convenes actors across the battery value chain to align on sustainability performance expectations for batteries around principles of transparency, traceability, accountability and circularity. The organization’s Battery Passport is an emerging global sustainability reporting and certification scheme for batteries, which can help supply chain companies demonstrate their commitment to build supply chain transparency, while managing reputation risk and becoming more resilient to supply chain disruptions.

-

The Taskforce on Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets was a multi-stakeholder initiative working “to scale effective and efficient voluntary carbon markets”. Members, including buyers and sellers of carbon credits, standard setters, civil society, and academics, were focused on recommending solutions to issues compromising the integrity and effectiveness of voluntary carbon markets, including ongoing concerns about the social impacts of carbon projects. The Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market was one of the outcomes of this initiative.

Alternative Models

- A growing share of food commodities are now marketed as value-added (sustainable) products. California-based B-Corp Uncommon Cacao supplies raw cocoa beans to artisan chocolate makers disconnected from world market prices. It aims to provide a transparent alternative to commodity exchange and certified cocoa by setting fixed farm gate and export prices annually to help farmer incomes grow.

- In September 2019, Mars launched “Our Palm Positive Plan”, which is focused on transforming their “palm supply chain to deliver deforestation-free palm oil and advance respect for human rights”. A key element of their approach is simplifying, validating and making their palm oil supply chain more transparent, including publication of their palm oil suppliers and mills, which declined from more than 1500 to less than 100 in the initial stages of their commitment. They have also focused on fostering and building long-term relationships with suppliers based on their alignment to and performance against criteria set by Mars, including criteria focused on targeting damaging recruitment fees typically paid by migrant plantation workers. As of 2024, the company reports 100% traceability to mill level and 96.3% to plantation level, with 99.8% of its palm oil certified under the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) standards. Mars has also made commitments to responsible cocoa procurement.

- An impact investing fund created by Danone, Firmenich, Mars and Veolia with respect to vanilla, offered a 10-year commitment, cooperative and a minimum price, through an “innovative model where formers and industry players share both the benefits and risks.” The project estimates that 60% of cured vanilla’s value will go back to farmers (compared to initially observed shares of 5% to 20%).

- Amsterdam-based startup Sourcery is a global sourcing and digital trade platform that aims to connect brands, manufacturers, traders and growers in the cotton supply chain. The platform enables concrete, verifiable data on the conditions around cotton growing – tracked by and licensed to the farmers who grow it – to be attached to the cotton traded on international markets, which has the potential to increase transparency and traceability of cotton supply chains.

Other tools and Resources

- Finance Against Slavery & Trafficking (FAST) is a multi-stakeholder initiative that works to mobilize the financial sector against modern slavery and human trafficking. They offer a number of tools, including a connection and risk tool, as well as a leverage practice matrix.

- SOMO (2024) Facing the facts: carbon offsets unmasked is a series of articles focused on the human dimension of corporate carbon offsets and the associated voluntary carbon markets.

- SEIA (2021). Solar Supply Chain Traceability Protocol is a set of recommended policies and procedures designed to identify the source of a product’s material inputs and trace the movement of these inputs throughout the supply chain.

- Public Eye (2019) Agricultural Commodity Traders in Switzerland – Benefitting from Misery? Details how agri-food commodity traders are linked to human rights violations and how power asymmetry needs to be addressed

- PWC (2024) Climate risks to nine key commodities: Protecting people and prosperity

- Global Rights Compliance (2025) Risk at the Source: Critical Mineral Supply Chains and State-Imposed Forced Labour in the Uyghur Region

- Blas, J., & Farchy, J. (2021). The world for sale: Money, power, and the traders who barter the Earth’s resources. Oxford University Press.

- IHRB (2018) The Commodity Trading Sector: Guidance on Implementing the UNGPs is a tool for the commodities trading sector as a whole in developing a shared practice of responsible trading which is consistent with international standards relevant for the respect of human rights.

- SOMO (2018) Global Mica Mining and the Impact On Children’s Rights is a mica-focused report that maps global production of a commodity and seeks to identify direct or indirect links to child labor or any other relevant children’s rights violations.

- OECD-FAO Guidance for Responsible Agricultural Supply Chains provides guidance for enterprises across the agricultural supply chain, from the farm to the consumer, anchored by a “framework on risk-based due diligence.”

- The BHRRC Transition Minerals Tracker which provides information on the human rights implications of the seven key commodities vital to the low carbon transition.

- International Cocoa Initiative which works to protect the rights of children and adults in cocoa-growing areas in West Africa.

Citation of research papers and other resources does not constitute an endorsement by Shift of their conclusions.

Business Model Red Flags

Business Model Red Flags  Tool for Indicator Design

Tool for Indicator Design