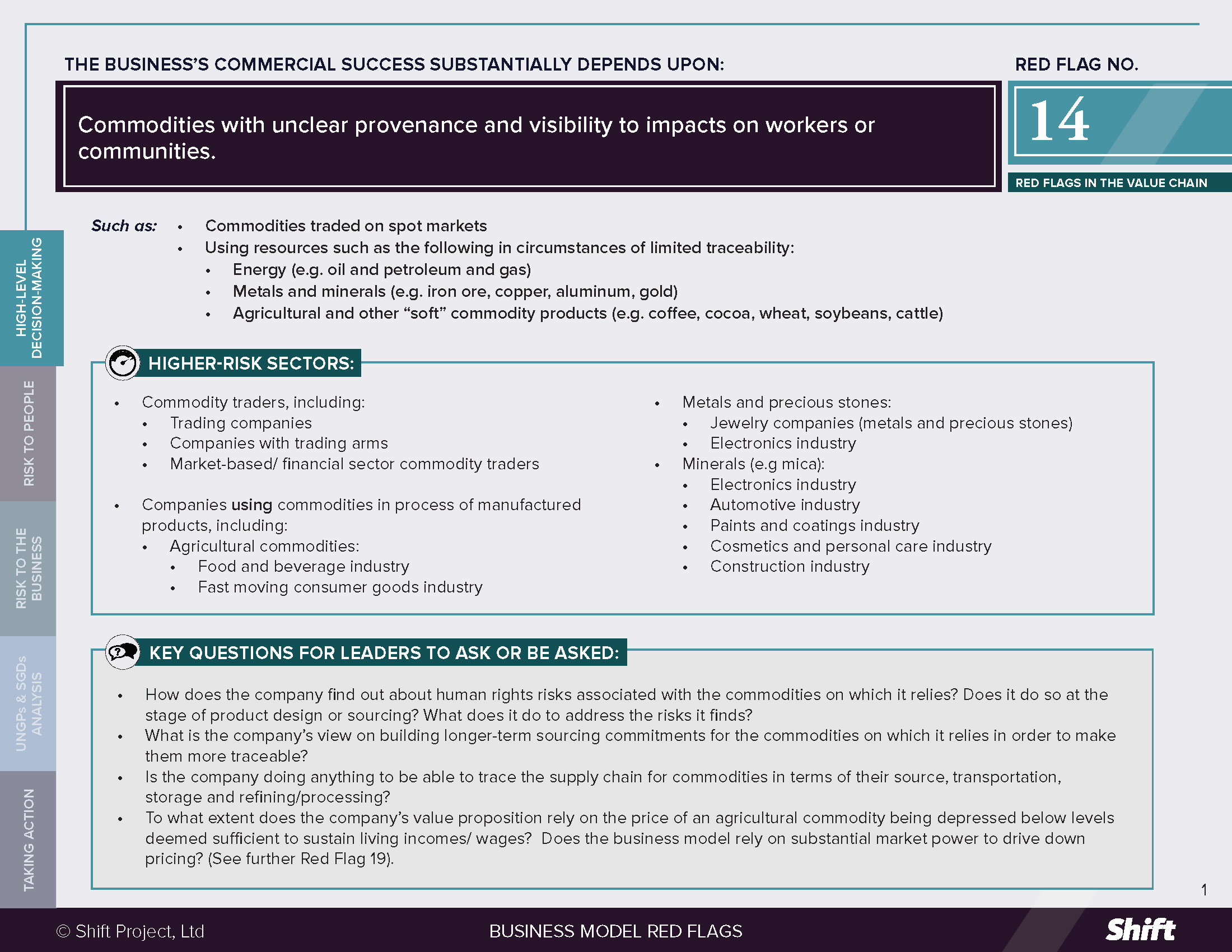

RED FLAG # 14

Commodities with unclear provenance and visibility to impacts on workers or communities.

For Example

- Commodities traded on spot markets

- Using resources such as the following in circumstances of limited traceability:

- Energy (e.g. oil and petroleum and gas)

- Metals and minerals (e.g. iron ore, copper, aluminum, gold)

- Agricultural and other “soft” commodity products (e.g. coffee, cocoa, wheat, soybeans, cattle)

Higher-Risk Sectors

- Commodity traders, including:

- Trading companies

- Companies with trading arms

- Market-based/ financial sector commodity traders

- Companies using commodities in process of manufactured products, including:

- Agricultural commodities:

- Food and beverage industry

- Fast moving consumer goods industry

- Metals and precious stones:

- Jewelry companies (metals and precious stones)

- Electronics industry

- Minerals (e.g mica):

- Electronics industry

- Automotive industry

- Paints and coatings industry

- Cosmetics and personal care industry

- Construction industry

- Agricultural commodities:

Questions for leaders

- How does the company find out about human rights risks associated with the commodities on which it relies? Does it do so at the stage of product design or sourcing? What does it do to address the risks it finds?

- What is the company’s view on building longer-term sourcing commitments for the commodities on which it relies in order to make them more traceable?

- Is the company doing anything to be able to trace the supply chain for commodities in terms of their source, transportation, storage and refining/processing?

- To what extent does the company’s value proposition rely on the price of an agricultural commodity being depressed below levels deemed sufficient to sustain living incomes/ wages? Does the business model rely on substantial market power to drive down pricing? (See further Red Flag 19).

How to use this resource. ( Click on the “+” sign to expand each section. You can use the side menu to return to the full list of red flags, download this Red Flag as a PDF or share this resource. )

Understanding Risks and Opportunities

Risks to People

- IHRB notes that commodities can be associated with adverse human rights impacts “at the point of production or extraction e.g. unfair working conditions, activities taking place in absence of adequate community consent, child and forced labor, health and safety abuses, discrimination of migrant workers, resettlement of communities without Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC), abuses of public/private security forces infringing workers’, indigenous peoples’, and communities’ rights.” In addition, where lowest cost is the largest business driver, e.g. in the commodities market, farmers, fishermen and smallholders have limited influence in negotiating terms of trade and receive an ever-diminishing share of the fruits of their labor. (See further Red Flags 1 and 19).

- As just one example, sheet mining of mica is a labor-intensive process, and is predominantly carried out by the very poor and vulnerable in low-wage countries. Mica mining, particularly in illegal small-scale artisanal mines, has been associated with child labor; 22,000 child laborers were identified in two areas of India, which, geographically, covered less than half of the so-called “mica mining belt.”

- Where commodities of unknown provenance are bought, sold, traded and hedged, purchasing companies in the value chain focus on price, defined specifications and quality standards rather than where the materials came from or under what conditions they were produced. It becomes difficult for companies upstream in the value chain to influence these decisions so as to address potential negative impacts on the rights of people in the value chain.

- Transparency, shortening of supply chains and longer-term commitments from buyers can “demystify complex supply chains,” and allow “different actors [to] identify and minimize risks and improve conditions on the ground and inform whether and where progress is being made.”

Risks to The Business

- Business Continuity Risks: Extreme price pressure on farmers and other workers at source can undermine availability of product and stability of supply.

- Reputational, Operational and Legal Risks: The company risks being involved in business relationships with disreputable organizations or individuals, including groups using forced or child labor or providing unsafe working environments, or may be financially supporting conflict. Operational challenges and even legal risks can arise where such connections come to light and the business must act reactively to exclude such sources from their value chain. Where traceability to individual companies is limited, entire industries can face civil society pressure to improve (e.g. in the case of palm oil).

- Business Opportunity: Focusing on improved livelihoods for people within the supply chain helps to bring them into the consumer base; failure to do so foregoes this opportunity. Opportunities for price reduction and new sources can be unlocked:

- Barry Parkin, Chief Procurement and Sustainability Officer of Mars, has noted that supply chains are “broken.” In an article arguing that the “commodity era is over,” he identifies win-win opportunities to “mov[e] beyond commodities that are bought and sold in markets where the lowest cost is the largest business driver,” and “[shift] to long-term models for corporate buying that are anchored on building mutuality, reliability, resilience and risk management into the core of our buying patterns.”

What the UN guiding principles say

*For an explanation of how companies can be involved in human rights impacts, and their related responsibilities, see here.

- Companies risk being directly linked to human rights impacts as a result of unknown and therefore unaddressed practices associated with the commodities going into their products.

- Where companies ought to be aware of risks associated with commodities incorporated in their products, including, for example, where a commodity is overwhelmingly sourced from one location where it is associated with human rights impacts, the company may be contributing to impacts if it fails to use its leverage to try to address the impacts, either alone, or in collaboration with others.

Possible Contrubutions to the SDGs

Addressing impacts on people associated with this red flag indicator can contribute to a variety of SDGs, depending on the impacts associated with the commodities. This may include, for example:

SDG 1: Eradication of poverty in all its forms.

SDG 8: Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all, in particular: Target 8.7 Eradication of forced labor, modern slavery and human trafficking, securing the prohibition and elimination of the worst forms of child labor, including the recruitment and use of child soldiers, and ending child labor in all its forms by 2025.

SDG 10: Reduce inequality within and among countries.

SDG 12: Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns, in particular: Target 12.6 Encourage companies, especially large and transnational companies, to adopt sustainable practices and to integrate sustainability information into their reporting cycle.

SDG 16: Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels, in particular: Target 16.2 End abuse, exploitation, trafficking, and all forms of violence against and torture of children.

Taking Action

Due Diligence Lines of Inquiry

- Which commodities that we use may be of higher risk from a human rights perspective, based on known information about potential source countries?

- Where information about impacts associated with the commodity is scant, how can we learn from known information about human rights impacts associated with other commodities sourced from the same area?

- Which partnerships, including with peers, international organizations, academics or NGOs, can we leverage to gain greater transparency or ensure traceability? Where no initiatives exist, can we create one?

- What opportunities exist/ can we create to build longer-term sourcing relationships?

Mitigation Examples

*Mitigation examples are current or historical examples for reference, but do not offer insight into their relative maturity or effectiveness.

- In 2018, the BMW Group and Codelco, a Chilean copper mining company, signed an agreement to cooperate on a sustainable and transparent supply of copper. In the “decommoditized” copper market, prices reflect differences in levels of certification.

- Many large consumer goods companies are disclosing the source of their palm oil through the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, including Unilever, which, in 2018 announced that it was “the first consumer goods company to publicly disclose the suppliers and mills it sources from” (both directly and indirectly), and Nestle, which has committed to achieving RSPO sustainable certification for 100% of its palm oil by 2023. In November 2019, the RSPO announced “shared responsibility” rules, that will require RSPO members who buy palm oil to increase the proportion of their sustainable purchases by 15% every year or face fines and possible suspension.

- Rather than prioritizing short-term electricity contracts, Mars is establishing long-term, country-level contracts in Mexico, the United Kingdom and the United States in an effort to contribute to addressing the environmental and social impacts of climate change. In this way, “electricity is no longer a commodity, but a long-term investment within which business is a market maker not simply a price taker.”

Alternative Models

- A growing share of food commodities are now marketed as value-added (sustainable) products. California-based B-Corp Uncommon Cacao supplies raw cocoa beans to artisan chocolate makers disconnected from world market prices. It aims to provide a transparent alternative to commodity exchange and certified cocoa by setting fixed farm gate and export prices annually to help farmer incomes grow.

-

An impact investing fund created by Danone, Firmenich, Mars and Veolia with respect to vanilla, offers a 10-year commitment, cooperative and a minimum price, through an “innovative model where formers and industry players share both the benefits and risks.” The project estimates that 60% of cured vanilla’s value will go back to farmers (compared to initially observed shares of 5% to 20%).

Other tools and Resources

- IHRB (2018) The Commodity Trading Sector: Guidance on Implementing the UNGPs is a tool for the commodities trading sector as a whole in developing a shared practice of responsible trading which is consistent with international standards relevant for the respect of human rights.

- Parkin (2018) Is the Commodity Era Over? is an article by the Chief Procurement and Sustainability Officer of Mars discussing the need for companies to “move beyond commodities that are bought and sold in markets where the lowest cost is the largest business driver.”

- SOMO (2018) Global Mica Mining and the Impact On Children’s Rights is a mica-focused report that maps global production of a commodity and seeks to identify direct or indirect links to child labor or any other relevant children’s rights violations.

- OECD-FAO Guidance for Responsible Agricultural Supply Chains provides guidance for enterprises across the agricultural supply chain, from the farm to the consumer, anchored by a “framework on risk-based due diligence.”

- The BHRRC has launched an updated Transition Minerals Tracker tool, which provides information on the human rights implications of the six key commodities vital to the transition to a net-zero carbon economy.

Business Model Red Flags

Business Model Red Flags  Tool for Indicator Design

Tool for Indicator Design