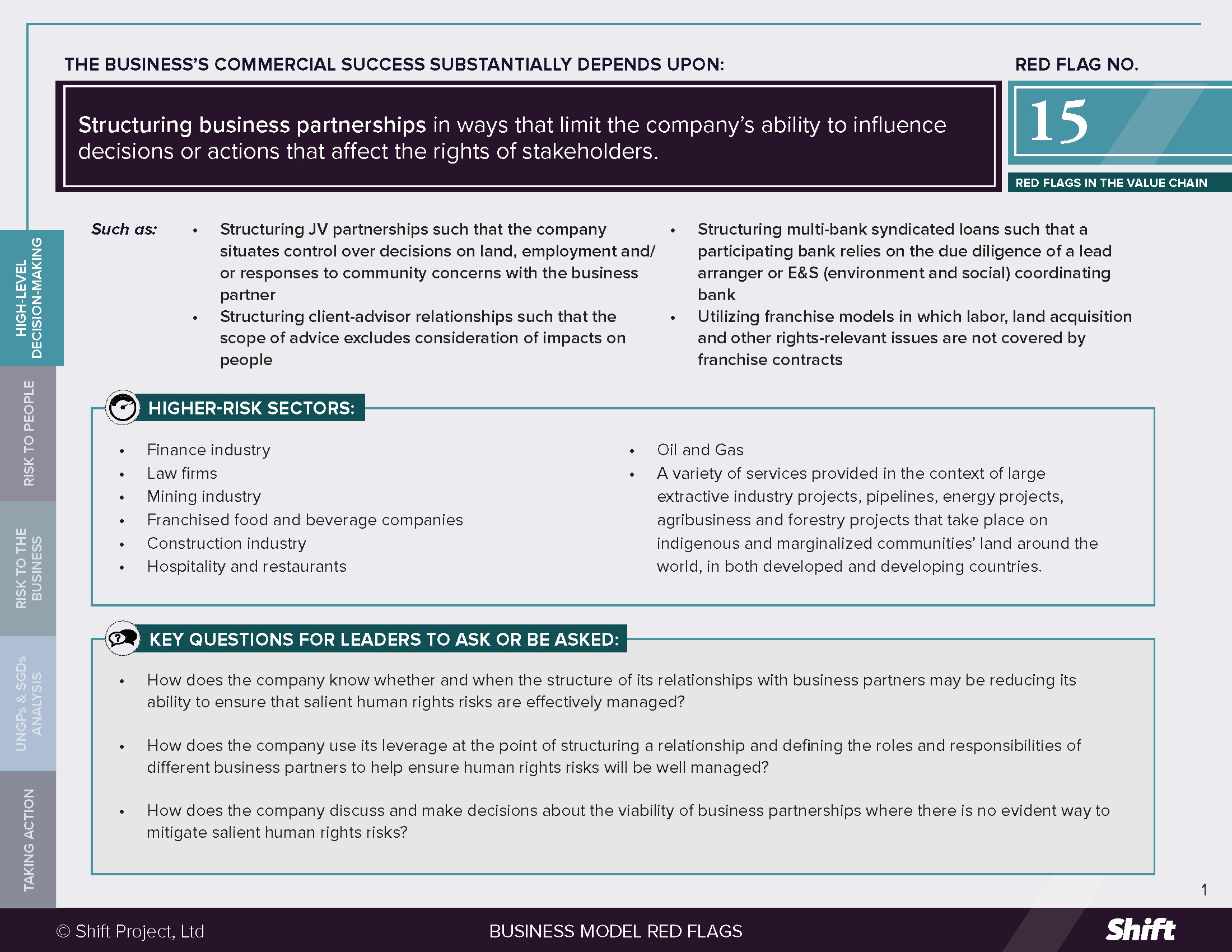

RED FLAG # 15

Structuring business partnerships in ways that limit the company’s ability to influence decisions or actions that affect the rights of stakeholders.

For Example

- Structuring JV partnerships such that the company situates control over decisions on land, employment and/or responses to community concerns with the business partner

- Structuring client-advisor relationships such that then scope of advice excludes consideration of impacts on people

- Structuring multi-bank syndicated loans such that a participating bank relies on the due diligence of a lead arranger or E&S (environment and social) coordinating bank

- Utilizing franchise models in which labor, land acquisition and other rights-relevant issues are not covered by franchise contracts

Higher-Risk Sectors

- Finance industry

- Law firms

- Mining industry

- Franchised food and beverage companies

- Construction industry

- Hospitality and restaurants

- Oil and Gas

- A variety of services provided in the context of large extractive industry projects, pipelines, energy projects, agribusiness and forestry projects that take place on indigenous and marginalized communities’ land around the world, in both developed and developing countries.

Questions for Leaders

- How does the company know whether and when the structure of its relationships with business partners may be reducing its ability to ensure that salient human rights risks are effectively managed?

- How does the company use its leverage at the point of structuring a relationship and defining the roles and responsibilities of different business partners to help ensure human rights risks will be well managed?

- How does the company discuss and make decisions about the viability of business partnerships where there is no evident way to mitigate salient human rights risks?

How to use this resource. ( Click on the “+” sign to expand each section. You can use the side menu to return to the full list of red flags, download this Red Flag as a PDF or share this resource. )

Understanding Risks and Opportunities

Risks to People

The way in which companies decide to structure their business relationships can have an effect on their ability to meet their human rights responsibilities. In particular, companies may routinely structure relationships in ways that limit their leverage over business partners.

Below are examples of ways in which companies structure relationships that may lead to a reduction in their ability to identify, prevent, mitigate and account for human rights impacts, or may reduce their perception of their responsibility to do so.

- In a syndicated loan, this may arise where the bank:

- relies on human rights due diligence conducted or commissioned by another participating bank in the syndicate;

- has little (direct) interaction with the E&S coordinating bank and/or the other participating banks on human rights impacts;

- has little interaction with stakeholders potentially affected by the project or those representing their interests

- has no influence over the creation or effective management of grievance mechanisms for affected stakeholders.

- In a JV partnership, this may arise where one party takes sole or primary responsibility for communication and dispute resolution with third parties, or where a company situates control over decisions on land and employment with the partner. This can be particularly problematic where the partner with this responsibility is an enterprise wholly or partially owned by a government that has a history of causing or ignoring impacts on vulnerable groups in the country, and the company has little practical leverage available to it.

- In a franchising relationship, this may arise where contracts retain franchisor control over businesses’ methods, procedures and standards, but not set out requirements on – nor accept responsibility for – rights-related issues such as employment practices, land acquisition, and environmental issues.

- In an advisory relationship, such as a lawyer-client relationship, this may arise where the advisor limits (or accept their client’s instructions to limit) their advice to exclude some or all potential impacts on human rights, at best closing the door to an important avenue for leverage held by advisors, and at worst playing a role in rendering it more likely that the client will impact rights through the relevant activities. (See related discussion on the role of the corporate legal advisor here).

In circumstances such as those above, a responsibility gap can emerge where neither business partner is engaged with addressing potential impacts, or where the contractual responsibility to do so is situated with a partner less able to do so. Further, a remedy gap emerges where neither business partner engages with grievances, impacting stakeholders’ right to remedy.

Risks to the Business

- Operational, Financial and Reputational Risks: A company’s understanding and implementation of its own responsibility in relation to impacts can be undermined when it structures a relationship in ways that limit its own scope for action and its accountability.

- For example, risks can arise where there are mistaken assumptions that due diligence conducted or commissioned by the E&S coordinating bank in a syndicated loan for project finance is sufficiently thorough. High profile examples of community conflict halting projects have highlighted that each financier is expected to know (and to show) that the HRDD conducted meets expectations: according to Banktrack, banks participating in the financing of the Dakota Access Pipeline “found themselves on the receiving end of the #DefundDAPL divestment campaign after the project violated Indigenous People’s rights – estimated to have cost them between US$8 and $20 billion in deposit withdrawals.”

- Legal Risks: The have been several lawsuits seeking to hold US company McDonald’s responsible for the treatment of franchise workers. In the United States the responsibility of franchisors to assume responsibility for employment conditions is a contested area. The company has stated that “franchisees are independent businesses that want to make their own decisions about hiring, pay and other matters.” Worker advocacy groups have “argued that many companies use contracting and franchising as ashield from responsibility for workers who make their business possible.” In 2020, a complaint was brought to the Dutch National Contact Point against McDonald’s on the basis that the company had not met OECD guidelines which “require due diligence by institutional shareholders in companies to ensure responsible business conduct.” The complainants alleged that due to “systemic sexual harassment” at franchised restaurants, the company had “neglected to act to create a safe workplace” for franchise employees.

- Business Opportunity Risks: Where advisors do not advise clients appropriately on the human rights risks associated with corporate decisions or activity, they risk losing repeat business when that advice proves inadequate in practice. The International Bar Association notes that:

- “There is growing recognition that a strong business case exists for respecting human rights and that the management of risks, including legal risks, increasingly means that lawyers, and particularly business lawyers, need to take human rights into account in their advice and services. The UNGPs are relevant to many areas of business legal practice, including but not limited to corporate governance, reporting and disclosure, litigation and dispute resolution, contracts and agreements, land acquisition, development and use, resource exploration and extraction, labour and employment, tax, intellectual property, lobbying, bilateral treaty negotiation, and arbitration.”

What the UN Guiding Principles say

*For an explanation of how companies can be involved in human rights impacts, and their related responsibilities, see here.

The parties to a business relationship may decide to allocate formal responsibilities in a particular way in their agreements – including responsibilities for identifying and addressing human rights risks. However, that does not remove them from any responsibility should human rights harms occur. For example, a company will still have a responsibility as a result of being linked to (and in some cases potentially contributing to) human rights impacts:

- In the context of a JV:

- whether it is a majority or minority stakeholder;

- whether or not it has primary responsibility for communication and dispute resolution with third parties;

- In the context of advice to clients:

- regardless of unilateral or agreed caveats with respect to what the advice does and does not address;

- In the context of syndicated loans for project finance:

- regardless of decisions on who will conduct/lead due diligence.

Similarly, a franchisor will still be linked (or potentially contributing) to impacts caused by franchisees vis-à-vis franchise employees.

Business relationships that are structured in these ways will typically affect the company’s ability to exercise leverage to mitigate human rights risks or impacts unless specific measures are included to address this. Where human rights impacts were foreseeable and the company still took on a role where its control or leverage was limited, this may be seen to suggest that the company contributed by omission to impacts caused by a business partner.

Possible Contributions to the SDGs

Where a company retains and uses leverage with business partners to strengthen respect for human rights, it can contribute to various SDGs. It may also build the capacity of its partners to contribute to the SDGs, by helping them understand and implement their own responsibilities, thereby contributing to:

SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals, in particular: Target 17.6 Enhance the global partnership for sustainable development, complemented by multi-stakeholder partnerships that mobilize and share knowledge, expertise, technology and financial resources, to support the achievement of the sustainable development goals in all countries, in particular developing countries. Target 17.17 Encourage and promote effective public, public-private and civil society partnerships, building on the experience and resourcing strategies of partnerships.

Taking Action

Due Diligence Lines of Inquiry

- Do we clearly communicate our human rights expectations to our partners?

- For joint ventures with significant human rights risks, do we ensure that legal and other agreements underpinning the ventures provide the necessary basis to ensure that human rights are respected in their operations? (See OHCHR and Business Dilemmas Forum)? For example:

- How do our agreements with partners allocate roles with relevance to the human rights of stakeholders, such as decisions on land,employment or dispute resolution with third parties?

- How do we ensure our partners carry out these roles in ways that respect human rights?

- Do we have pre-agreement on how human rights incidents and disputes will be dealt with, once they arise?

- Do we have the right to conduct audits of overall human rights compliance?

- Do we have the right to terminate the agreement in the event that human rights non-compliances are identified during such audits and are not rectified within a reasonable amount of time?

- How thorough are our due diligence procedures and do they include human rights risks? Do we tend to defer to or rely on processes of another partner without our own investigations? Are we prohibited from making contact with stakeholders by our agreements with business partners? How do we identify gaps between others’ processes and international human rights standards? How do we address these gaps? Do we look for early opportunities (e.g. at point of market entry) to create leverage? Do we include a leverage mapping into our due diligence procedure?

- Does the structure or duration of the relationship significantly limit our leverage?

- Do we have or participate in an effective grievance mechanism through which affected persons can raise human rights issues related to our partners’ activities?

- Do our agreements with partners contain confidentiality or consent requirements that constrain our ability to disclose information about our operations in higher risk areas? If so how do we ensure that stakeholders have access to information relevant to understanding how they may be affected and to claiming their rights?

Mitigation Examples

*Mitigation examples are current or historical examples for reference, but do not offer insight into their relative maturity or effectiveness.

There are numerous examples of a company seeking to influence the behavior of a business partner, including where that partner has primary responsibility for areas that impact rights.

(The following anonymized examples are adapted from Shift’s publication, Using Leverage in Business Relationships to Reduce Human Rights Risks).

- Shadowing Partners: A company has shadowed a joint venture partner as it conducted a stakeholder engagement.

- Seconding Staff: A company has seconded staff to a JV operation to lead on community relations and/or human rights risk management.

- Shared Audits: A company has conducted an internal audit of its own human rights performance at an operation, and shared results with key business partners, with an invitation/ offer to collaborate with them on addressing shared challenges, as well as on future such audits.

In the context of syndicated loans, responsible banks individually evaluate projects or borrowers against their own human rights and project-specific policies, including to address gaps between standards applied by the E&S (environment and social) coordinating bank and expectations under the UN Guiding Principles. Even where a bank has a smaller ticket in a syndicated loan, recognized expertise in the field of social impacts has allowed such banks to exert outsize leverage with other participating banks to ensure potential social impacts are adequately considered and addressed.

- Contract Provisions: Companies have negotiated various human rights-related provisions in contracts with business partners that created leverage later in the relationship. Examples include contract provisions that:

- set out a commitment to meet certain standards (e.g., Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights, IFC Performance Standards);

- give the company (even when a junior partner) the lead in managing human rights-related issues or in staffing the community relations function at an extractive project;

- require a higher voting majority of the board on human rights-related issues.

- Company Policies and Code of Conducts: Companies have negotiated the inclusion of references to their own standards or policies in joint agreements, such as a Code of Conduct or policies on security. In the context of non-operated joint ventures, Total reports that it “make[s] ongoing efforts so that the operating party applies equivalent principles to ours.”

- Multi-stakeholder (Industry) Initiatives (MSIs) with Human Rights Commitments: A company may require or suggest that a partner join a credible multi-stakeholder (industry) initiative, or may jointly join an initiative with them: for example, PNG and FGB jointly joined the FLA in furtherance of “a desire to drive long-term change in the palm oil supply chain for the industry as a whole.” Companies have [also] highlighted partners’ existing commitments – including those made in the context of MSIs – when seeking to exert leverage to bring the partner’s attention to addressing impacts.

- Introducing a Non-Essential Partner with Strong Standards: Companies have involved the International Finance Corporation as a small percentage financier of a project, so they could reference their Performance Standards in project contracts and in broader discussions with project partners.

- Strategic Role: Some companies identify the committees with oversight of areas likely to be associated with salient human rights impacts associated with a joint venture (e.g. health and safety; procurement or sustainability), and ensure they play a strategic role in them, even when they are a minority partner.

- Capacity Building: A company may extend training and other capacity and awareness building activities to partners and/or industry players to enhance and to bolster the likelihood of their conducting adequate human rights due diligence.

Alternative Models

There may be opportunities for increasing leverage to address actual and potential human rights impacts in a joint venture context through a coordinated approach. For example, in 2016 BHP created the Non-Operated Joint Ventures (NOJV) Asset within Minerals Americas in order to establish effective engagement with its joint venture partners and companies in line with BHP’s Charter. The Asset creates a single point of accountability with responsibility for all non-operated joint ventures in Minerals Americas and its purpose includes having transparency over JV companies’ risks and opportunities, in an active feedback process, whilst maintaining the JV company’s management independence.

Other tools and resources

General:

- Shift (2015) Human Rights Due Diligence in High Risk Circumstances: Practical Strategies for Businesses: highlights strategies and practices that certain businesses have found most effective when conducting human rights due diligence in high risk circumstances. It includes “higher risk business relationships” such as those with business partners.

- Shift (2013) Using Leverage in Business Relationships to Reduce Human Rights Risks addresses various business relationships, including joint ventures.

Joint Ventures:

- IHRB (2012) Chapter 5: Respect for Human Rights in Joint Ventures Relationships of State of Play – Human Rights in Business Relationships: assists, inter alia, with identification and mitigation of human risks arising in connection with JV partners.

Finance:

Project Finance:

- Shift (2018) Enhancing the Alignment of the Equator Principles with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights: A Public Summary of Shift’s Advice to the Equator Principles Association.

- Equator Principles (2020) Equator Principles EP4.

- Equator Principles (2020) Guidance note on Implementation of human rights assessments under the Equator Principles.

- Equator Principles (2020) Guidance note on evaluating projects with affected indigenous peoples.

Corporate Lending:

- IRBC Agreements, The Dutch Banking Sector Agreement (2019) DBA’s Analysis of Severe Human Rights Issues in the Palm Oil Value Chain and Follow-up actions.

- IRBC Agreements, The Dutch Banking Sector Agreement (2019) Increasing leverage working group: Progress report phase I working group paper.

Legal Advice:

- International Bar Association (2016) Practical Guide on Business and Human Rights for Business Lawyers and Business and Human Rights Guidance for Bar Associations.

- A4ID, The UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights: A guide for the legal profession: provides an analysis, with case examples, of:

- a law firms’ implementation of rights and responsibilities in client relationships;

- the relationship between the UNGPs and codes of professional conduct for the legal profession.

- IBA, Handbook for company and commercial lawyers on Business and Human Rights: about the links between different kinds of risks (drafted with help and advice from practitioners from some big law firms).

- UN Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner (2011) Principles for responsible contracts: Integrating the management of human rights risks into state-investor contracts.

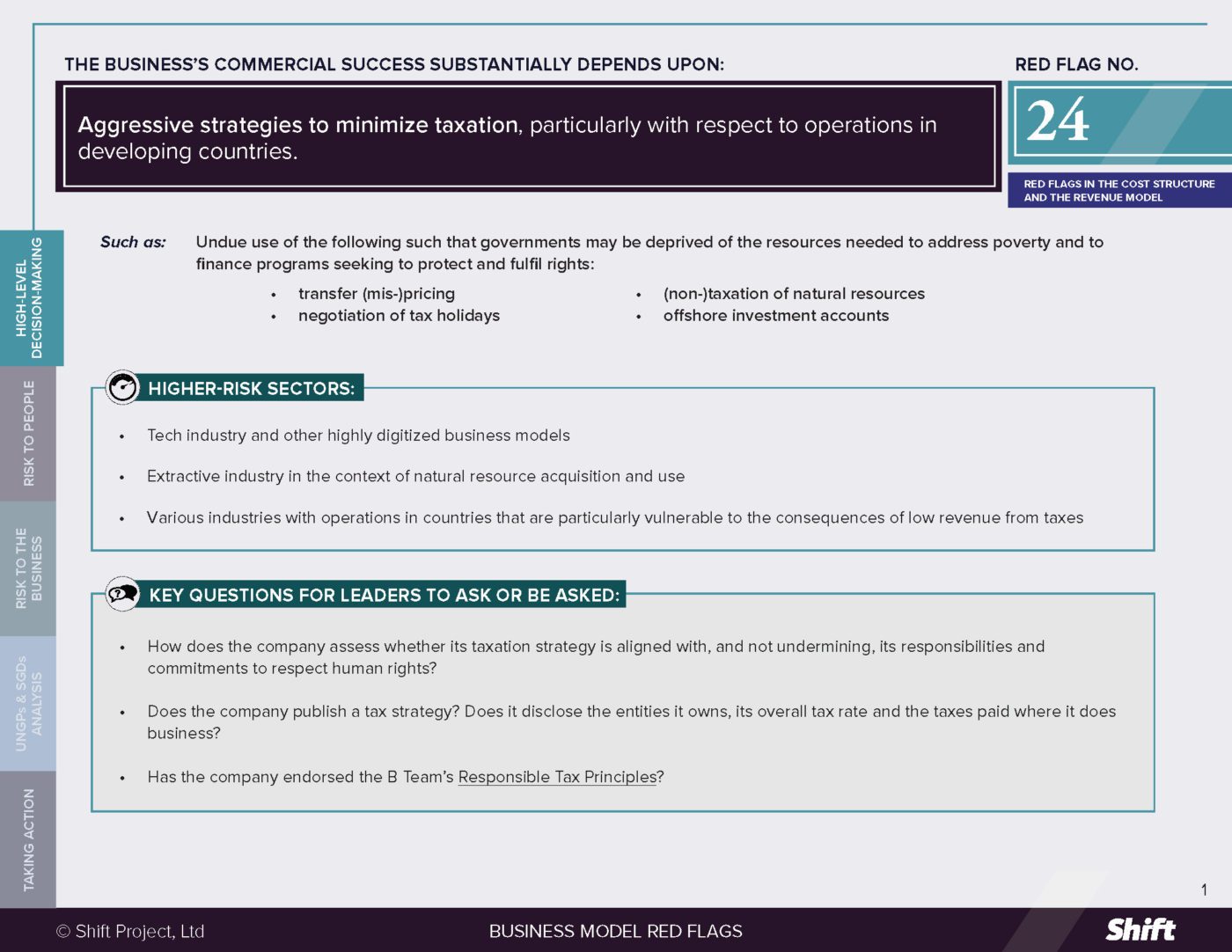

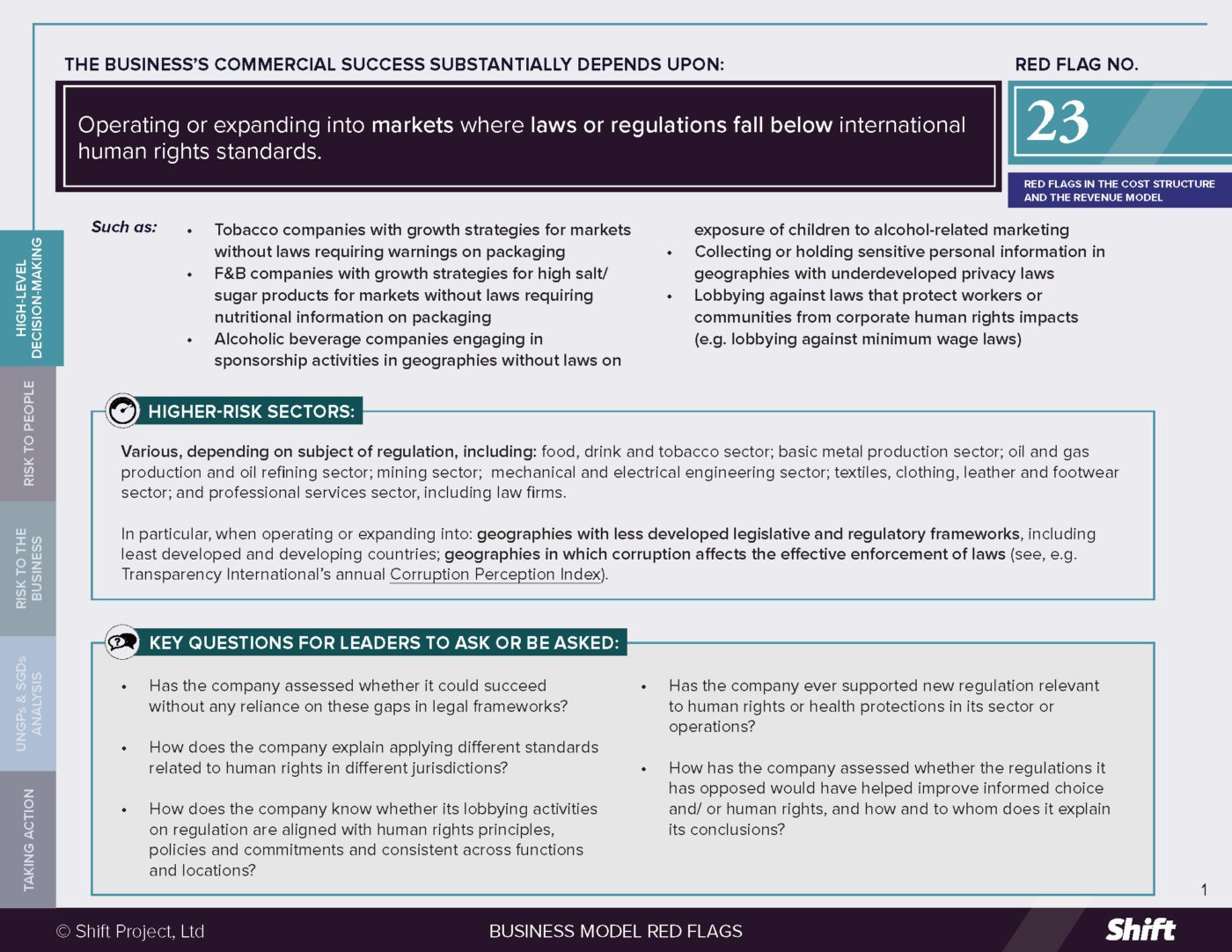

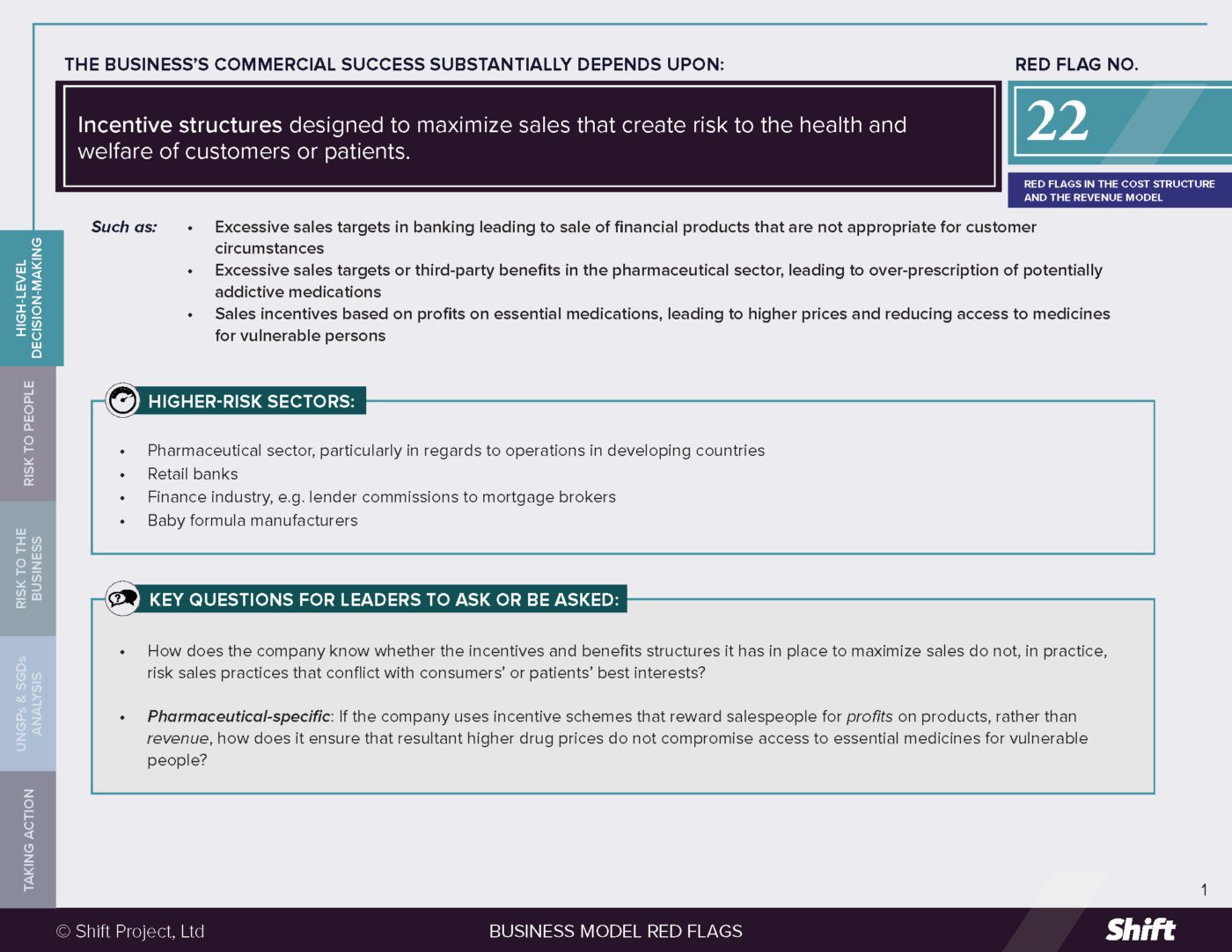

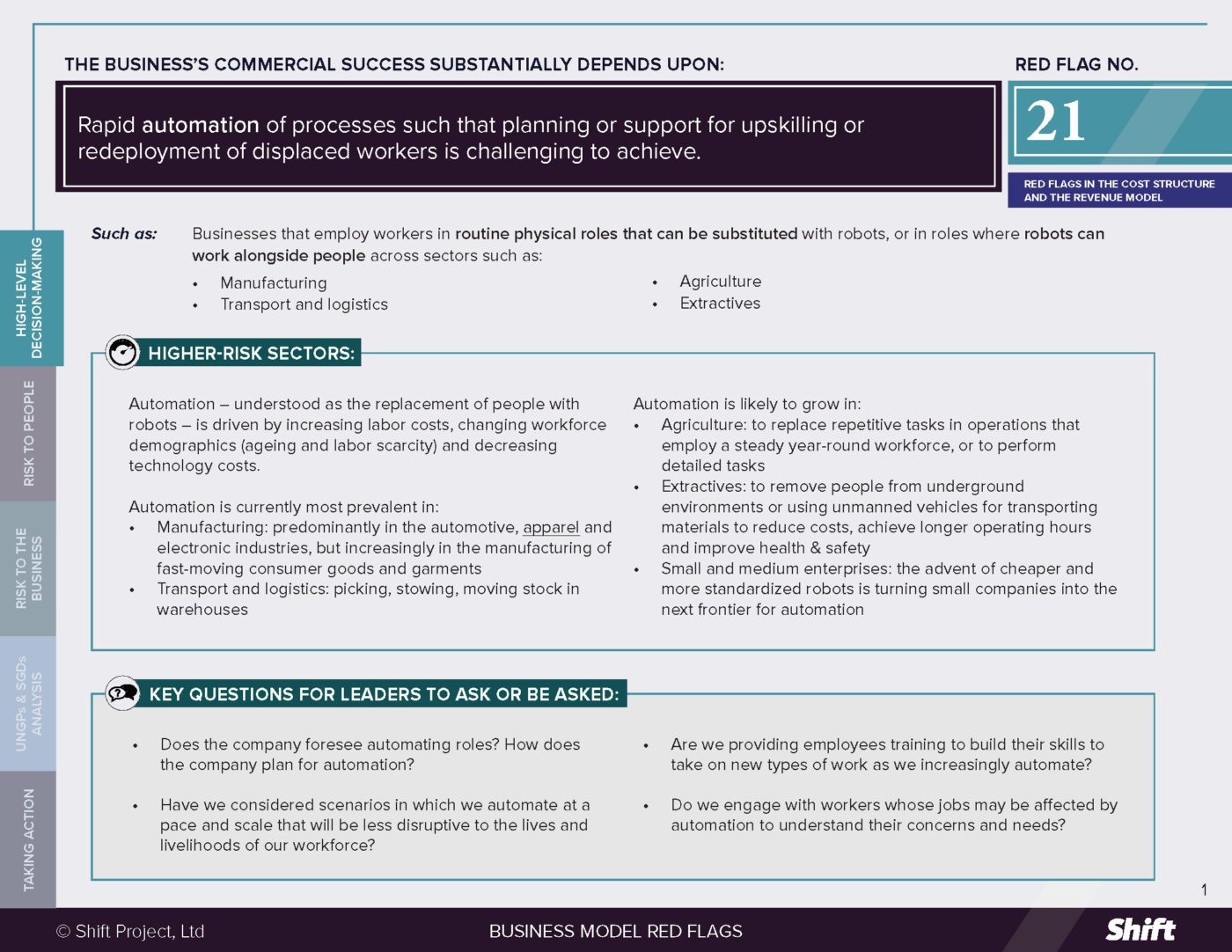

Business Model Red Flags

Business Model Red Flags  Tool for Indicator Design

Tool for Indicator Design