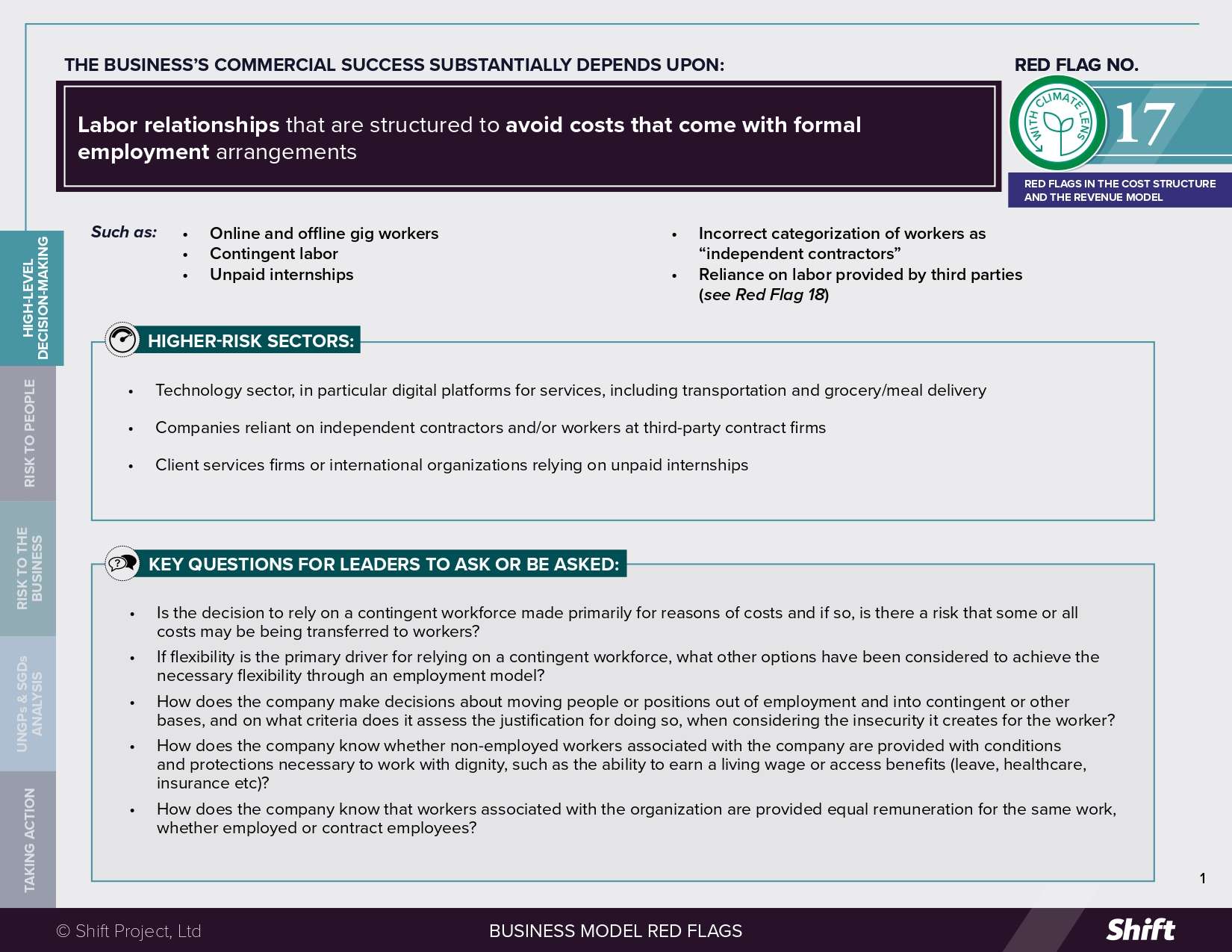

RED FLAG # 17

The business’s commercial success substantially depends upon labor relationships that are structured to avoid costs that come with formal employment arrangements

For Example

- Online and offline gig workers

- Contingent labor

- Unpaid internships

- Incorrect categorization of workers as “independent contractors”

- Reliance on labor provided by third parties (see red flag 18)

Higher-Risk Sectors

- Technology sector, in particular, digital platforms for services, including transportation and grocery/meal delivery

- Companies reliant on independent contractors and/or workers at third-party contract firms

- Client services firms or international organizations relying on unpaid internships

Questions for Leaders

- Is the decision to rely on a contingent workforce made primarily for reasons of costs and if so, is there a risk that some or all costs may be transferred to workers?

- If flexibility is the primary driver for relying on a contingent workforce, what other options have been considered to achieve the necessary flexibility through an employment model?

- How does the company make decisions about moving people or positions out of employment and into contingent or other bases, and on what criteria does it assess the justification for doing so, when considering the insecurity it creates for the worker?

- How does the company know whether non-employed workers associated with the company are provided with conditions and protections necessary to work with dignity, such as the ability to earn a living wage or access benefits (leave, healthcare, insurance, etc.)?

- How does the company know that workers associated with the organization are provided equal remuneration for the same work, whether employed or contract employees?

How to use this resource. ( Click on the “+” sign to expand each section. You can use the side menu to return to the full list of red flags, download this Red Flag as a PDF or share this resource. )

Understanding Risks and Opportunities

Risks to People

Gig economy

The gig economy is growing rapidly but defining and measuring gig work can be challenging. According to the World Bank Group, in 2023 between 145 million and 435 million individuals worldwide were engaged in the gig economy, which represents between 4% and 12% of the global workforce, and with considerable growth anticipated, particularly in developing countries.

Classifying an employee as an independent contractor can reduce costs to the company, such as payroll taxes and premiums for workers’ compensation – by as much as 30%.

Further, non-traditional employment – such as gig work – has the potential to provide some benefits for some workers, such as independence and flexibility in choosing where, when and for whom they work. However, such benefits are not always realized. For example, gig workers can be committed to one employer through variable hour contracts, which significantly decreases their flexibility and increases uncertainty. Where these non-traditional employment relationships are exploited, it can exacerbate existing vulnerabilities by shifting costs and risk to workers (without commensurate increase in financial compensation).

Some groups have referred to excessive use of such employment relationships as a “misclassification business model”, whereby the company “engages the people who actually carry out the core business, and over whose work significant control is exerted, as independent contractors instead of employees”.

Further, in geographies without regulatory protections for workers, this structure can deny workers access to the benefits that are tied by domestic law to a direct employment relationship, including:

-

Access to anti-harassment and discrimination protections (Right to non-discrimination; Right to just and favorable conditions of work).

-

Minimum wage and overtime protections (Right to equal pay for equal work; Right to fair/living wage).

-

Safe working conditions (Right to health and Right to life)

-

Right to organize and bargain collectively (Freedom of association)

-

Access to unemployment insurance and workers’ compensation (Right to an adequate standard of living; Right to just and favorable conditions of work).

Internships

When used appropriately, internships can provide a valuable entry or insight into a company or industry. When used inappropriately, they can amount to individuals undertaking “real work of real value with no economic support”. Where independent contractors or interns undertake jobs similar to regular workers in an organization, but for less pay or access to benefits, issues of equal pay and non-discrimination arise. Moreover, internships that are unpaid can limit access to opportunity for those, including in the global South, who do not have the financial resources to work for free, reinforcing persistent economic and social inequalities (See PSI).

The gig economy’s business model, built on flexible, on-demand labor, can leave workers particularly exposed to the escalating risks of climate change. Gig workers, especially those responsible for ride-hailing and delivery services, are increasingly required to work through heatwaves, storms, and poor air quality, often without access to sick leave, workers’ compensation, or protective equipment. At the same time, the high volume of short, on-demand trips and deliveries can contribute to urban congestion and air emissions, thereby potentially exacerbating the precarious working conditions.

Risks to the business

Regulatory, financial and legal risks:

-

In Canada, the Ontario Labour Relations Board ruled in 2020 that foodora couriers are dependent contractors, giving them the legal right to organize and join a trade union.

-

In 2024 the US Department of Labor instituted a new rule that made it more difficult for companies to classify workers as independent contractors, thus potentially bolstering legal protections and compensation for workers and potentially increasing company insurance liabilities.

-

In July 2024, the California Supreme Court upheld Prop 22, a new hybrid scheme that, while allowing Uber, Lyft, and DoorDash to keep drivers as contractors, guarantees 120% minimum wage, health care stipends, and some injury protections.

-

In the UK, court cases are reclassifying gig economy workers. In February 2021, the UK Supreme Court unanimously ruled that Uber drivers are “workers”, not independent contractors. Thereafter in November 2024, a UK Employment Tribunal ruled that European ride-hailing group Bolt’s UK drivers must be classified as “workers” rather than independent contractors, entitling them to rights such as the national minimum wage (including for time logged into the app), paid annual leave, and potentially over £200 million in back pay for around 15,000 claimants. The tribunal found that Bolt exercised significant control over drivers, rejecting arguments that they operated as independent businesses. While Bolt had introduced certain benefits in mid-2024 (such as holiday pay and pensions) without reclassifying drivers, it is now reviewing the judgment and considering an appeal. The Bolt ruling closely mirrors the landmark Uber v Aslam case, the outcome of which held that Uber drivers were “workers” and were therefore entitled to the benefits attached to that status. These cases may have far-reaching implications for the gig economy in the UK.

-

Denver Labor, the US city of Denver’s labor enforcement office, issued citations to two businesses – Instawork and Gigpro – seeking over USD 1 million in restitution and fines because they misclassified their workers as independent contractors, resulting in hundreds of workers being paid less than minimum wage and being denied the right to paid sick leave.

-

In 2023, the San Francisco City Attorney filed a lawsuit against Qwick, an on-demand hospitality staffing company, for “illegally misclassifying its workers and denying them guaranteed protections wages and benefits”. The City Attorney stated “Qwick is inequality disguised as innovation, a staffing company with an app that is in flagrant violation of labor and employment laws. It uses convenience and flexibility to mask its decision to deny workers their rights.” In 2024, Qwick agreed to a USD2.5 million settlement with the City of San Francisco.

-

The EU Platform Work Directive, which Member States are required to transpose into national law by December 2, 2026, aims to enhance rights for gig economy workers by establishing a legal presumption of employment for platform workers under certain conditions, thereby granting them access to benefits like minimum wage and paid leave. It mandates transparency in algorithmic management, requiring platforms to disclose how automated systems affect working conditions and to provide human oversight over significant decisions.

-

The legality of unpaid internships remains in a grey zone, with conflicting case law and a number of lawsuits filed by interns asserting they undertook the work of employees, for free.

Financial risks

-

In April 2020 the FT noted that Jim Chanos, the US investor, had warned in March that “he was shorting the stock of companies that relied on ‘gig workers’, on the basis that the crisis would change social and political attitudes to businesses relying on this precarious workforce”.

Staff recruitment/ Retention risks and Reputational Risks

-

Organizations that rely heavily on unpaid or temporary labor, especially where it replaces entry-level jobs, face risks associated with lack of retention of staff with progressively increasing knowledge/skills. Further, they may miss opportunities associated with a more diverse workforce (age, family responsibilities, socio-economic status) by only drawing on a pool of talent with the means to remain unpaid for the period of work.

-

Reputational risks may arise where workers mobilize to highlight their concerns about working conditions. For example in India, a country that hosts one of the fastest growing gig economies, there was a four day protest in Hyderabad, during which workers emphasized that the online grocery delivery service Zepto had not responded to workers’ concerns about lack of employee protections, including health insurance and accident coverage. The national gig workers union group also submitted a complaint to the state Labor Department highlighting alleged exploitative labor practices by the company.

Business Opportunity Risks:

-

In response to Spain’s 2021 “Rider Law”—which requires app-based delivery companies to classify riders as employees— British online food delivery company Deliveroo announced its withdrawal from the Spanish market and officially ceased operations there on 29 November 2021.

What the UN guiding principles say

Where a company routinely offers poorer pay and conditions to workers of a particular employment status, especially where this intersects with ethnicity or immigration status, age or other factors, they risk causing a negative impact.

Where a company’s remuneration of contract workers (or the hours of work it makes available to them) renders it difficult for a worker to maintain a living wage as they juggle multiple jobs, their health and safety is compromised on the job, or they have no freedom of association, they risk contributing to an impact.

Possible Contributions to the SDGs

Addressing impacts to people associated with this red flag can contribute to, inter alia:

-

SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth, in particular target 8.8 on protecting “labor rights and promot[ing] safe and secure working environments for all workers, including migrant workers, in particular women migrants, and those in precarious employment [emphasis added].

-

SDG10 Reduced Inequalities, in particular target 10.4: Adopt policies, especially fiscal, wage and social protection policies, and progressively achieve greater equality

-

SDG14 Climate Action, in particular target 14.1: Strengthen resilience and adaptive capacity to climate-related hazards and natural disasters in all countries.

Taking Action

Due Diligence lines of Inquiry

-

Does the company or its supply chain partner(s) use substantial numbers of non-employed workers (e.g. gig workers, contract workers)?

-

Does the company have clear guidance to managers on the appropriate use of non-employed workers?

-

How does the company engage with workers on working hours? Are workers guaranteed a certain number of hours, do they have a regular schedule, or do they have input into the hours they work?

-

Do contract workers have the same protections under the law and regulations as the company’s own employees? Consider

-

Access to anti-harassment and discrimination protections

-

Minimum wage and overtime protections

-

Access to unemployment insurance and workers’ compensation

-

-

If not, does the company apply its policies to contract workers in order to bridge this gap?

-

How does the company know if non-employed workers associated with the organization are vulnerable to extreme weather, such as heat waves? What measures does the company have in place to address these types of impacts?

-

Do contract workers have the same opportunities to organize as the company’s own employees?

-

Does the company or a supplier have a deliberate strategy to use contract laborers in order to limit union organization?

-

Does the company use paid or unpaid interns?

-

Are interns undertaking similar work to paid employees?

Mitigation Examples

-

Since 2015 Microsoft has required that its vendors provide contract employees with at least 15 days of paid holiday and sick leave and since 2018, paid family leave.

-

In India, Swiggy and Zomato (two food delivery services), have taken steps to address the extreme heat to which their workers are increasingly exposed and which is increasingly compromising worker health, as well as the service delivery times. For example, Swiggy has set up 900 “recharge zones” and Zomato has 450 “rest points” where food delivery workers can rest, use the washrooms, and drink water.

-

getTOD, a South African platform for tradespeople such as electricians and plumbers, has gained recognition for its commitment to fair labor practices, including by ensuring workers earn at least a living wage, have clear and transparent contracts, and are assured freedom of association.

-

We Pay Our Interns is an organization of NGOs in Geneva who “joined forces on the common understanding that promoting human rights worldwide must first be applied to basic human rights in their own structures” and committed to promoting a basic pay (stipend) for their interns.

Alternative Models

-

A “groundbreaking” 2019 agreement between Hermes Parcelnet (now Evri) and the GMB union was notable as the UK’s first deal offering gig economy couriers a new “Self-Employed Plus” (SE+) status, combining self-employment flexibility with guaranteed pay, holiday entitlement, and union representation. It set a precedent for improving worker protections without fully reclassifying gig workers as employees. Building on this, Hermes introduced pension auto-enrollment for SE+ couriers by the end of 2022 and added maternity and paternity leave benefits starting March 2022. In March 2021, the company also raised courier pay rates and introduced additional service incentives.

-

Some transformations have occurred as a result of legal pressure. For example in Spain, following fines amounting to €205 million for using a false self-employment structure, delivery company Glovo officially announced that all 20,000 of its riders in Spain will transition to employee status from July 1, 2025, abandoning the self-employed model entirely.

Other tools and resources

On gig workers

-

Fairwork is a website that articulates fair work principles, rates and ranks the working conditions of digital platforms, and produces publications on types and locations of gig work.

-

Human Rights Watch (2025), “The Gig Trap”. This report explores how major digital labor platforms in the U.S. misclassify gig workers as independent contractors, thereby denying them essential labor rights.

-

World Bank Group (2023) Working Without Boarders: The Promise and Peril of Online Gig Work

-

Business and Human Rights Resource Centre’s Gig Economy Portal

-

Business and Human Rights Resource Centre (2019), “The Future of Work: Litigating Labour Relationships in the Gig Economy”, Corporate Legal Accountability Annual Briefing 2019: Briefing focuses on the “misclassification of workers as “independent contractors” in the gig economy – and the resulting erosion of labour rights”.

-

Gig Workers Collective (a non-profit organization of gig worker activists)

-

Prosus (2024) Livelihoods in a Digital World: A brief for good work in the digital economy

On gig workers and climate change

-

Lu, S et al. (2024) “When Gig Work Meets Extreme Weather”, Harvard Business Review.

-

Vu, A.N. and D.L. Nguyen (2024) “The gig economy: The precariat in a climate precarious world” World Development Perspectives, Vol. 34.

-

TGPWU & Heatwatch (2024), Impact of Extreme Heat on Gig Workers: A Survey Report details the heat-related issues facing Hyderabad’s gig workers as well as proposed recommendations for addressing these issues.

On internships

On contract workers

-

Shift/Mondiaal’s “Respecting Trade Union Rights in Global Value Chains: Practical Approaches for Business” (2019) contains diagnostic questions on outsourcing and contract Labor.

Citation of research papers and other resources does not constitute an endorsement by Shift of their conclusions.

Business Model Red Flags

Business Model Red Flags  Tool for Indicator Design

Tool for Indicator Design