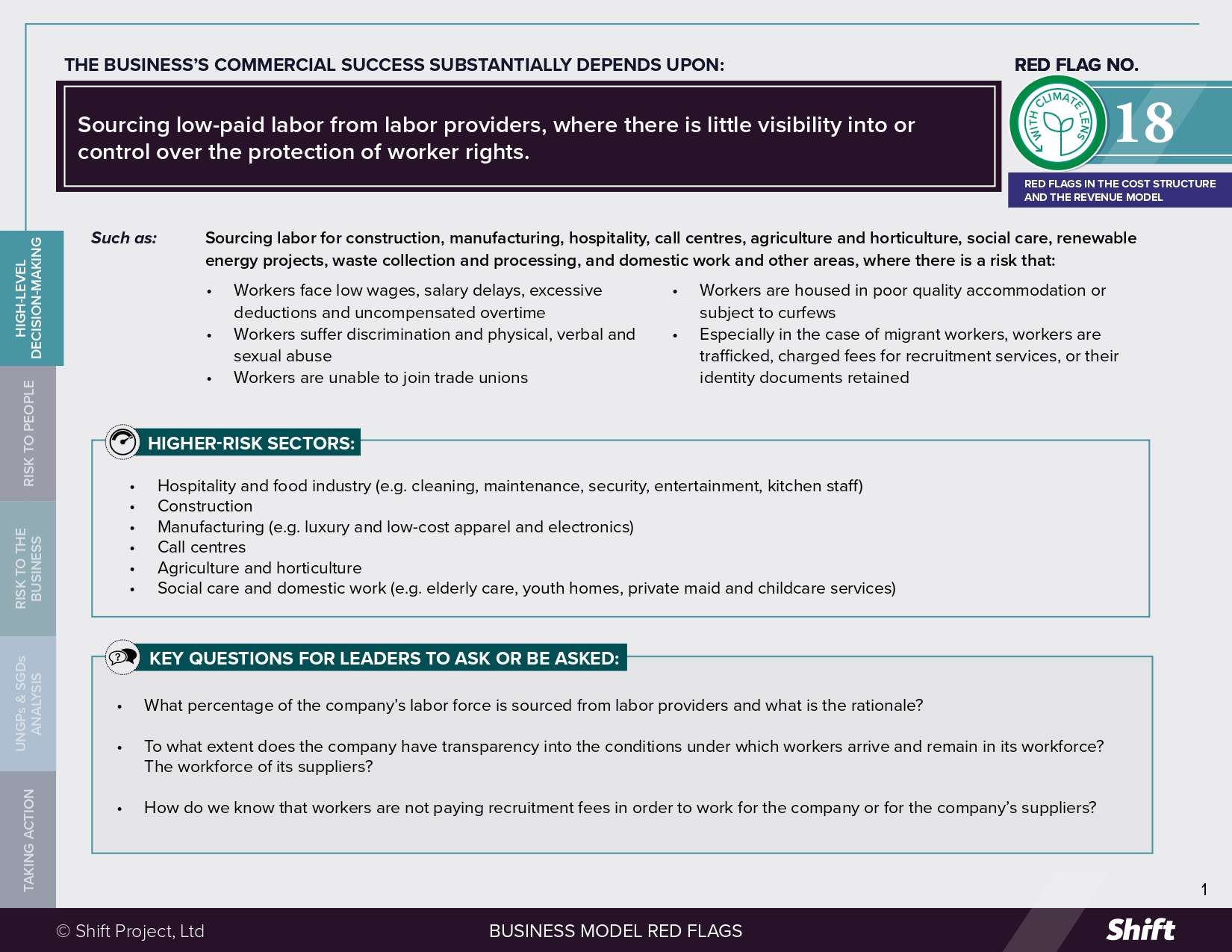

RED FLAG # 18

Sourcing low-paid labor from labor providers, where there is little visibility into or control over the protection of worker rights

For Example

Sourcing labor for construction, manufacturing, hospitality, call centers, agriculture and horticulture, social care, renewable energy projects, waste collection and processing, and domestic work and other areas, where there is a risk that:

- Workers face low wages, salary delays, excessive deductions and uncompensated overtime

- Workers suffer discrimination and physical, verbal and sexual abuse

- Workers are unable to join trade unions

- Workers are housed in poor-quality accommodation or subject to curfews

- Especially in the case of migrant workers, workers are trafficked, charged fees for recruitment services, or their identity documents retained

Higher-Risk Sectors

- Hospitality and food industry (e.g., cleaning, maintenance, security, entertainment, kitchen staff)

- Construction

- Manufacturing (e.g., luxury and low-cost apparel, and electronics)

- Call centres

- Agriculture and horticulture

- Social care and domestic work (e.g., elderly care, youth homes, private maids and childcare services)

Questions for Leaders

- What percentage of the company’s labor force (both the company’s own workforce and its supply chain workers) is sourced from labor providers and what is the rationale?

- To what extent does the company have transparency into the conditions under which workers arrive and remain in its workforce? The workforce of its suppliers?

- How do we know that workers are not paying recruitment fees in order to work for the company or for the company’s suppliers?

How to use this resource. ( Click on the “+” sign to expand each section. You can use the side menu to return to the full list of red flags, download this Red Flag as a PDF or share this resource. )

Understanding Risks and Opportunities

Risks to People

-

People are the core business of employment and recruitment agencies. As such, labor providers can positively or negatively impact the employees they recruit for client companies and the agency workers they place, as well as their families, and local communities in the migrant worker’s home state.

-

Negative impacts can occur at all stages of the recruitment and employment process and affect workers’ rights, including their freedom from all forms of forced or compulsory labor; their right to just and favorable conditions of work; their right to privacy, women’s and migrant workers’ rights; the right to non-discrimination; the right to form and join a trade union and the right to collective bargaining; and the right to an adequate standard of living.

-

Cross-border recruitment of migrant workers intersects with heightened vulnerability where individuals experiencing extreme poverty may feel their choices are limited and/or lack knowledge about their rights in the host state. Moreover, regulation that ties a worker’s immigration status to a particular employer (who acts as a sponsor), or which requires the worker to gain employer permission to exit the country, places the worker in a position of particular vulnerability: if the worker experiences abuse or exploitation, or sees his/her personal documents retained, it can be difficult to seek redress out of fear of losing a job and immigration status.

-

Recent investigations into the practices of unscrupulous recruitment and employment agencies have revealed serious abuses in a variety of sectors:

-

A 2024 Oxfam report exposes how over 2.4 million migrant workers underpin European agriculture, particularly in Spain, Italy, France, Poland, and the Netherlands. Many are recruited through labor providers and informal intermediaries, which increases the risks of wage theft, unsafe housing, discrimination, and violence. Women migrants are especially at risk, facing lower pay and documented sexual exploitation.

-

Key findings from a report into the hotel industry in the United Arab Emirates and Qatar highlighted testimonies by some workers (mainly housekeepers, restaurant staff, security guards, drivers and stewards) who reported receiving half of the salary they were initially promised; ATM cards and other valuable documents were kept from them, deductions were frequently made from salaries for illegitimate reasons and their freedom of movement was severely curtailed.

-

There have been numerous reports of debt bondage and forced labor with respect to migrant workers in the electronics sector in Malaysia which supplies major brands in the Global North. There have been reports that workers, primarily from Nepal, Bangladesh, Indonesia and Myanmar, have not received the wages and accommodation promised by agencies, and moreover were forced to pay high sums (over $4,000 USD) to become employed in Malaysia. Workers claim their passports were confiscated, they received violent threats and were deceived about major elements of their work agreements.

-

-

As the global economy accelerates its transition toward a low-carbon and climate-resilient future, demand for labor is shifting to the expansion of low carbon sectors, such as renewable energy. While such activities are vital for climate mitigation, they are increasingly dependent on low-paid, often migrant labor, sourced through labor providers. As in the other scenarios explored here, some labor providers impose high recruitment fees, provide workers with insecure contracts, withhold wages, impose excessive overtime, provide abusive living and working conditions, restrict worker mobility, any or all of which can leave workers vulnerable to exploitation and hazardous conditions.

-

Simultaneously, the physical impacts of climate change already being felt globally — such as drought, extreme weather and environmental degradation — play a critical role, not only in driving vulnerable workers into precarious migration, but also at destination worksites across several sectors where workers are often exposed to dangerous climatic conditions, such as prolonged heat exposure, with limited access to health and safety protections. This intersection of unregulated labor recruitment and harsh outdoor working conditions, particularly prominent in the construction and agricultural sectors, undermines both human rights and climate resilience, while further reinforcing inequality.

Risks to The Business

|

What the UN guiding Principles say

|

A company that sources workers from a labor provider may cause negative impacts where, for example, it does not fulfill its part of the responsibility to ensure safe working conditions, or where it otherwise mistreats the workers on site, such as through discriminating practices, or limits the opportunity to join a legitimate trade union. In that case, the company should take the necessary steps to cease the impact, prevent its recurrence and provide any necessary remedy to the affected workers. A company that sources workers from a labor provider may contribute to impacts where it is aware of and tolerates the poor treatment of workers by the labor provider, or where it does not conduct proper due diligence to ensure that the workers sourced from the labor provider are not mistreated or otherwise negatively impacted. A company may also contribute to negative impacts where it makes last minute requests of or for workers, pushing the labor provider to breach labor standards in order to deliver. In cases of contribution, a company should cease its contribution to the impact and contribute to remedy for the affected workers to the extent of its own contribution to the situation. A company that sources workers from a labor provider may be linked to negative impacts, such as those associated with the payment of recruitment fees, if such practices occur despite proper due diligence and credible attempts at using leverage over the labor provider to prevent or mitigate the impacts. |

Possible Contributions to the SDGs

Addressing impacts to people associated with this red flag can contribute to, inter alia:

SDG 5 Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls, in particular:

-

Target 5.2 End all forms of discrimination against all women and girls everywhere

-

Target 5.3 Eliminate all forms of violence against all women and girls in the public and private spheres, including trafficking and sexual and other types of exploitation

SDG 8 Decent Work and Economic Growth, in particular:

-

Target 8.5, By 2030, achieve full and productive employment and decent work for all women and men, including for young people and persons with disabilities, and equal pay for work of equal value

-

Target 8.7 Take immediate and effective measures to eradicate forced labor, end modern slavery and human trafficking and secure the prohibition and elimination of the worst forms of child labor, including recruitment and use of child soldiers, and by 2025 end child labor in all its forms

-

Target 8.8 Protect labor rights and promote safe and secure working environments for all workers, including migrant workers, in particular women migrants, and those in precarious employment

SDG 13 Climate Action, in particular:

-

Target 13.1 Strengthen resilience and adaptive capacity to climate-related hazards and natural disasters in all countries.

Taking Action

Due Diligence Lines of Inquiry

The questions below are prepared from the perspective of a company interrogating its own use of labor providers. However, they can be adapted for use in engaging with other companies in the value chain about their use of outsourced labor. In this case, they might be prefaced with the question “What percentage of your workforce is sourced from third party labor providers/ recruitment agencies?”

-

How does the company ensure protection of workers’ rights for outsourced labor? To what extent do policies and protections apply to temporary/agency workers?

-

Have we reviewed the labor provider’s Code of Conduct and other relevant policies to check whether they include commitments not to charge recruitment fees to workers and not to retain their identity documents? Are there any “red flags” present, e.g. where the labor provider is unwilling to provide details about their processes or where there are historical complaints or negative findings against the provider?

-

Is the labor provider offering “too good to be true” rates that would not allow it to meet minimum total wage costs (including sick pay and statutory holidays), business overheads, management costs, etc.?

-

Do we have a clear service agreement with the labor provider, including clauses on social compliance (no recruitment fees, no unlawful retention of documents and valuables) as well as detailed charge rates, a confirmation that workers will be paid, a clear agreement to ensure the health and safety of all workers as a shared responsibility between the labor user and provider?

-

Do we conduct checks or audits of our labor provider to check that proper recruitment and contractual arrangements are in place; wages paid are correct, on time and without improper deductions; there is no debt bondage, harsh treatment or intimidation; workers’ accommodation and working conditions are of an acceptable standard, etc.?

-

Are the auditors and our staff equipped to detect the potentially complex pressures, abuses and exploitation of workers by labor providers?

-

Are the workers on our site who work for labor providers aware of who to report problems to and are they likely to feel safe doing so? Are we sending the message that we take these issues seriously and are available to the workers who would want to raise issues? What is our process to handle any concerns or problems raised?

-

Do we integrate the physical impacts of climate change, such as extreme heat, into occupational health and safety requirements for our direct and indirect workforce?

Below is a set of questions to consider asking in interviews of labor providers (and workers, where applicable) especially in higher risks contexts.

-

Did the worker pay any money to the labor provider for the job?

-

Did the worker travel from abroad for the job? Did he/she pay transport costs? Is the worker charged for transport to work; how much?

-

Was the worker given a copy of the worker contract? Did he/she understand the content and expectations?

-

Has the worker retained his/her own identity documents?

-

How many hours a week does the worker work?

-

What hourly rate does the worker receive? Are there any deductions, other than standard ones?

-

Does the worker get paid regularly? Has the labor provider ever failed to pay the worker?

-

Is the worker regularly exposed to extreme heat or other climatic conditions for extended periods of time? If so, how are such conditions addressed by the labor provider/employer?

-

Where does the worker live? Is the accommodation provided by the labor provider? How many people is it shared with? How much rent does he/she pay?

-

Does the worker seem uncomfortable and are they willing to share any issues?

-

Do all the workers interviewed indicate they are happy and contented but do not seem so? Do they glance at anybody when answering questions?

Mitigation Examples

* Mitigation examples are current or historical examples for reference, but do not offer insight into their relative maturity or effectiveness.

Given the complex nature of the problem, often mitigation efforts take the form of sector-wide or cross-sectoral initiatives.

-

The Responsible Labor Initiative of the Responsible Business Alliance is a multi-industry, multi-stakeholder initiative focused on the rights of workers vulnerable to forced labor in global supply chains. Activities include engagement with recruitment agencies with respect to fees charged to workers, including capacity building and preferential treatment for responsible agencies, and the repayment of recruitment fees by manufacturers and buyers where fees have been charged to workers.

-

The Consumer Goods Forum’s Human Rights Coalition — Working to End Forced Labour is a CEO-led initiative working together as a Coalition to: implement forced labor-focused due diligence systems in their own operations; engage with suppliers to ensure due diligence coverage in upstream supply chains; and advocate for enabling policy environments to protect Workers’ rights and support business efforts.

-

Food industry: In 2020, several major UK retailers, including M & S, Tesco and Sainsbury’s, united to drive the responsible recruitment of workers in global supply chain by sponsoring the Responsible Recruitment Toolkit, a package of support for suppliers and recruitment businesses to better embed ethical and professional recruitment and labor supply practices.

-

Hospitality industry: Several labor rights initiatives are starting to take shape to tackle modern slavery and forced labor in the hospitality industry. The International Tourism Partnership’s (ITP) Principles on Forced Labour brings the world’s leading hotel groups together to tackle the three most problematic yet common employment practices that can lead to forced labor, especially amongst vulnerable workers: unlawful retention of passport and valuable possessions, recruitment fees and being indebted or coerced to work. The Shiva Foundation’s Stop Slavery Blueprint is a toolkit intended to address risk of modern slavery for the internal use of hotels and other stakeholders in the industry.

-

Apparel industry:

-

Fast Retailing and the International Organization for Migration collaborated to analyze Fast Retailing’s supply chain, diagnose high risk practices, enhance the capacity of sustainability staff to respond to human and labor rights challenges and adopt and implement production partner guidelines for fair and ethical recruitment.

-

The American Apparel and Footwear Association, which represents 1000 different apparel brands, partnered with the Fair Labour Association to develop a Commitment on Responsible Recruitment, which was enhanced and relaunched in 2023.

-

Alternative Models

Alternative models generally involve avoiding third party labor providers in circumstances of higher risk, in favor of direct employment relationships, to ensure greater visibility and control over hiring practices and working conditions.

-

In response to reports of forced labor linked to migrant recruitment practices in the electronics industry supply chain in Malaysia, HP released its Foreign Migrant Worker Standard in 2014. The standard goes beyond general industry practice in addressing forced labor – which primarily focuses on implementing policies banning recruitment fees – to require that the company’s suppliers directly employ any foreign migrant workers in their workforce. To help reinforce implementation, HP partnered with Verité to develop supplier guidance on transitioning to direct employment and ethical recruitment practices. See Shift’s analysis here.

-

One example of producer-led practices aimed at tackling forced labor in the form of Sumangali schemes in Southern India, is Penguin Apparel’s Program. The garment manufacturer has eliminated labor brokers and recruitment fees from its hiring processes, ensures local language translation of employment documents, provides training to workers on their rights, conducts audits of its own suppliers and contractors in the search for Sumangali schemes and educates its partners on social management systems. See Shift’s analysis here.

-

Unilever’s Joint Commitment on Sustainable Employment, signed in 2019 with IndustriALL and the IUF, restricts temporary contracts, bans zero hour contracts, ensures equal pay for equal work, and protects union rights across 300+ factories in 69 countries. It aims to strengthen job security and fair conditions for both direct and agency workers. In May 2025, while the agreement itself remained unchanged, Unilever guaranteed existing pay, benefits, and conditions for 6,000 European ice cream workers for three years following a planned corporate restructuring — exceeding the legal one-year requirement.

Other tools and Resources

-

Know the Chain & Business and Human Rights Resource Centre (2024) Good Practice Guide: Supply chain human rights due diligence.

-

Responsible Labor Initiative of the Responsible Labor Alliance.

-

Vérité: Fair Hiring Tool.

-

SOMO, Temporary agency work in the electronics sector: Discriminatory practices against agency workers (2012).

-

Business and Human Rights Resource Center, Inhospitable: How hotels in Qatar & the UAE are failing migrant workers (2019).

-

Business and Human Rights Resource Centre (2024) Rush to renewables: Toward migrant worker rights and a just energy transition in the Gulf.

-

Ethical Trading Initiative (2023) Tackling exploitation of migrant workers in Agriculture.

-

Oxfam International (2024) Essential but Invisible and Exploited: A literature review of migrant workers’ experiences in European agriculture.

-

ILO (2024) Ensuring safety and health at work in a changing climate.

-

Interfaith Center on Corporate Responsibility (2017) Best Practice Guidance on Ethical Recruitment of Migrant Workers

-

Dhaka Principles for Migration with Dignity.

-

International Labour Organization, Regulating International Labour Recruitment in the Domestic Work Sector: A Review of key issues, challenges and opportunities (2016).

Citation of research papers and other resources does not constitute an endorsement by Shift of their conclusions.

Business Model Red Flags

Business Model Red Flags  Tool for Indicator Design

Tool for Indicator Design