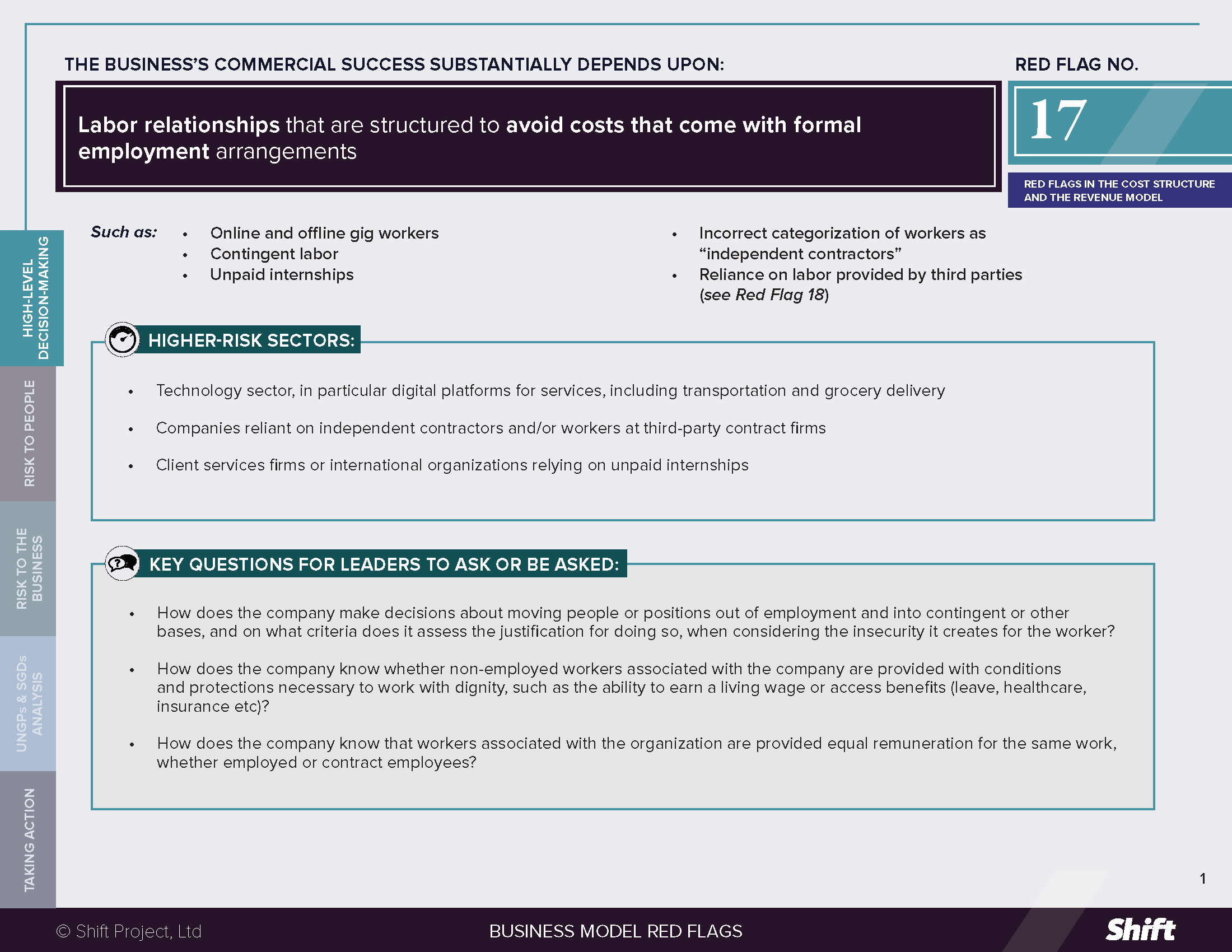

RED FLAG # 17

Labor Relationships that are structured to avoid costs that come with formal employment arrangements

For Example

- Online and offline gig workers

- Contingent labor

- Unpaid internships

- Incorrect categorization of workers as “independent contractors”

- Reliance on labor provided by third parties (see Red Flag 18)

Higher-Risk Sectors

- Technology sector, in particular digital platforms for services, including transportation and grocery delivery

- Companies reliant on independent contractors and/or workers at third-party contract firms

- Client services firms or international organizations relying on unpaid internships

Questions for Leaders

- How does the company make decisions about moving people or positions out of employment and into contingent or other bases, and on what criteria does it assess the justification for doing so, when considering the insecurity it creates for the worker?

- How does the company know whether non-employed workers associated with the company are provided with conditions and protections necessary to work with dignity, such as the ability to earn a living wage or access benefits (leave, healthcare, insurance etc)?

- How does the company know that workers associated with the organization are provided equal remuneration for the same work, whether employed or contract employees?

How to use this resource. ( Click on the “+” sign to expand each section. You can use the side menu to return to the full list of red flags, download this Red Flag as a PDF or share this resource. )

Understanding Risks and Opportunities

Risks to People

Gig economy

According to McKinsey, 20-30% of the workforce in the US and EU-15 countries is involved in the gig economy (although estimates vary).

Classifying an employee as an independent contractor can reduce costs to the company – like payroll taxes and premiums for workers’ compensation – by as much as 30%.

Non-traditional employment can have benefits for some workers, allowing them flexibility in choosing where, when and for whom they work.

However, where these relationships are exploited, it can exacerbate the vulnerability of already vulnerable individuals by shifting costs and risk to workers (without commensurate increase in financial compensation).

Some groups have referred to excessive use of non-traditional employment relationships as a “misclassification business model,” whereby the company “engages the people who actually carry out the core business, and over whose work significant control is exerted, as independent contractors instead of employees.”

When used inappropriately or in geographies without regulatory protections for non-traditional workers, the structure can deny workers access to the benefits that are tied by domestic law to a traditional employment relationship, including:

- Access to anti-harassment and discrimination protections (Right to non-discrimination; Right to just and favorable conditions of work).

- Minimum wage and overtime protections (Right to equal pay for equal work; Right to fair/living wage).

- Right to organize and bargain collectively (Freedom of association) Access to unemployment insurance and workers’ compensation (Right to an adequate standard of living; Right to just and favorable conditions of work).

Internships

When used appropriately, internships can provide a valuable entry or insight into a company or industry. When used inappropriately, they can amount to individuals undertaking “real work of real value with no economic support.” Where independent contractors or interns undertake jobs similar to regular workers in an organization, but for less pay or access to benefits, issues of equal pay and non discrimination arise. (Right to non-discrimination; Right to just and favorable conditions of work) Moreover, internships that are unpaid can “limit access to opportunity for ‘non-privileged’ people (particularly from the global South) who do not have the financial resources to work for free, exacerbating economic and global inequalities” (See PSI). (Right to just and favorable conditions of work; Right to fair/living wage; Right to equal pay for equal work).

Risks to the business

Financial risks

In December 2019, it was reported that,“venture capitalists are pulling back from [gig economy] start-ups … as the companies face pushback from workers and policymakers critical of their business models.” The Covid-19 outbreak of 2020 exposed inequalities experienced by those in non-employed positions and “moved the issue to the top of the agenda.” In April 2020 the FT noted that Jim Chanos, the US investor, had warned in March that “he was shorting the stock of companies that relied on “gig workers,” on the basis that the crisis would change social and political attitudes to businesses relying on this precarious workforce.”

Operational risks

Commentators have noted that notwithstanding business advantages, some companies also consider “major drawbacks” related to the gig economy, particularly “for employers who need a reliable, collaborative work force.” Moreover, the structure can make it difficult for companies to undertake interventions to increase hourly compensation of workers: research by economists employed by Uber found that when Uber raised the rates drivers are paid, the higher prices to riders led to a drop in demand for rides and therefore left hourly earnings little changed.

Staff recruitment/ Retention risks

Organizations that rely heavily on unpaid or temporary labor, especially where it replaces entry-level jobs, face risks associated with lack of retention of staff with progressively increasing knowledge/skills. Further, the may miss opportunities associated with a more diverse workforce (age, family responsibilities, socio- economic status) by only drawing on a pool of talent with the means to remain unpaid for the period of work.

Reputational and business continuity risks

Companies exploiting non-traditional labor may find themselves fighting for consumer acceptance and defending their reputation. Campaigns to support non-employed workers have gathered attention. Drivers for ride sharing platforms staged a driving protest in Boston in April 2020 demanding recognition as employees and paid sick leave. Employees at Google campaigned for better conditions for colleagues on contracts amid the coronavirus crisis in May 2020.

Legal and regulatory risks

- Concerns about worker welfare in non-traditional employment has led to court cases and new law. “Judges and regulators in France, the UK and New Jersey have rejected claims that [gig] workers are really self-employed.” In the United States, the California Supreme Court found in 2018 that a delivery driver was an employee of the courier and delivery company he drove for, despite the fact that the company had previously shifted its workers to independent contracts. Following this decision, the Californian legislature passed a bill requiring certain contract workers to be treated as regular employees, covered by minimum wage, overtime, unemployment insurance and other protections. Other US states are reportedly considering similar legislation. In Boston in early 2020, drivers for ride sharing platforms won the right to pursue wage claims in court, rather than in private arbitration.

- The legality of unpaid internships remains in a legal grey zone, with conflicting case law and a number of lawsuits filed by interns asserting they undertook the work of employees, for free.

What the UN guiding principles say

*For an explanation of how companies can be involved in human rights impacts, and their related responsibilities, see here.

Where a company routinely offers poorer pay and conditions to workers of a particular employment status undertaking similar work to employees, especially where this intersects with ethnicity or immigration status, age or other factors, they risk causing a negative impact.

Where a company’s remuneration of contract workers (or the hours of work it makes available to them) renders it difficult for a worker to maintain a living wage as they juggle multiple jobs, they risk contributing to an impact.

Possible Contributions to the SDGs

SGD 8: Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all, in particular Target 8.8 Protect labour rights and promote safe and secure working environments for all workers, including migrant workers, in particular women migrants, and those in precarious employment.

SDG 10: Reduce inequality within and among countries, in particular: Target 10.4 Adopt policies, especially fiscal, wage and social protection policies, and progressively achieve greater equality

Taking Action

Due Diligence lines of Inquiry

- Do we or our supply chain partner(s) use substantial numbers of non-employed workers (e.g. gig workers, contract workers)?

- Does we have clear guidance to managers on the appropriate use of non-employed workers?

- Do contract workers have the same protections under the law and regulations as our own employees?

- Consider: Access to anti-harassment and discrimination protections, Minimum wage and overtime protections, Access to unemployment insurance and workers’ compensation

- If not, do we apply its policies to contract workers in order to bridge this gap?

- Do contract workers have the same opportunities to organize as our own employees?

- Do we or a supplier have a deliberate strategy to use contract laborers in order to limit union organization?

- Do we use paid or unpaid interns?

- Can the primary beneficiary of the internship be considered to be the intern? Or is it rather is it us?

- Are interns undertaking similar work to paid employees?

Mitigation Examples

*Moreover, some examples listed below are proposals for mitigating actions that have come from data science and engineering research institutes.

- Fair compensation is integral to Unilever’s Sustainability Plan. The company conducted an internal review of the use of temporary and contract labor in all manufacturing operations in 2011. It has prepared guidance for managers on the circumstances in which temporary work is acceptable. It also widened the scope of its audit program under its Supplier Code to include third-party labor providers of temporary or contract workers at its factory operations. Unilever partnered with Oxfam in 2013 and 2016, including to understand and assess the use of contract labor in its Viet Nam operations and supply chain.

- Since 2015 Microsoft has required that its vendors provide contract employees with at least 15 days of paid holiday and sick leave and since 2018, paid family leave.

- During the Coronavirus pandemic of 2020, several companies decided to set up compensation funds for contractors impacted by the virus. The question has been asked as to whether “corporate generosity around the outbreak is a one-off event or the start of something bigger” for contract workers.

- We Pay Our Interns is an organization of NGOs in Geneva who “joined forces on the common understanding that promoting human rights worldwide must first be applied to basic human rights in their own structures” and committed to promoting a basic pay (stipend) for their interns.

Alternative Models

In a groundbreaking step for the gig economy, logistics provider Hermes Parcelnet engaged in a recognition deal with GMB Union under which self-employed workers can choose to become “self-employed plus” and receive benefits such as holiday pay, negotiated pay rates and union representation. In exchange, workers agreed to follow delivery routes specified by Hermes Parcelnet rather than delivering parcels in any order. (See IHRB 2019 for more information).

Other tools and resources

On gig workers

- Business and Human Rights Resource Centre (2019), “The Future of Work: Litigating Labour Relationships in the Gig Economy”, Corporate Legal Accountability Annual Briefing 2019: Briefing focuses on the “misclassification of workers as “independent contractors” in the gig economy – and the resulting erosion of labour rights.”

- Gig Workers Collective (a non-profit organization of gig worker activists).

On internships

On contract workers

- Shift/Mondiaal’s “Respecting Trade Union Rights in Global Value Chains: Practical Approaches for Business” (2019) contains diagnostic questions on outsourcing and contract Labor.

- Company example: Oxfam reports on Unilever operations in Viet Nam analyzed Unilever’s efforts to address precarious labor in Unilever’s operations and supply chain in 2013 and again in 2016.

- ITUC Report: Living with economic insecurity: women in precarious work also references submissions by IMF and IUF to SRSG John Ruggie on precarious work.

Business Model Red Flags

Business Model Red Flags  Tool for Indicator Design

Tool for Indicator Design