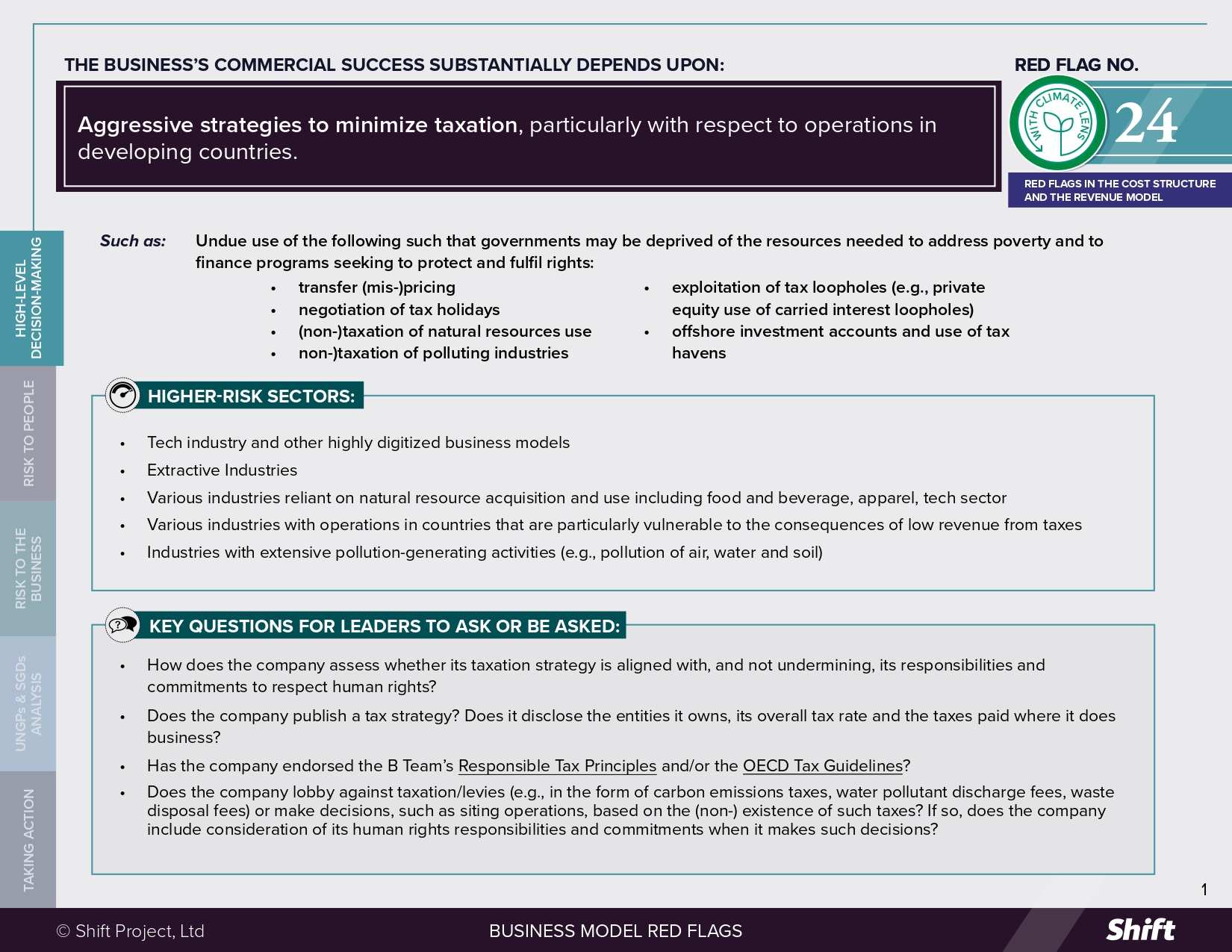

RED FLAG # 24

The business’s commercial success substantially depends upon aggressive strategies to minimize taxation, particularly with respect to operations in developing countries.

For Example

Undue use of the following such that governments may be deprived of the resources needed to address poverty and to finance programs seeking to protect and fulfil rights:

- transfer (mis-)pricing

- negotiation of tax holidays

- (non-)taxation of natural resources use

- (non-)taxation of polluting industries

- exploitation of tax loopholes (e.g., private equity use of carried interest loopholes)

- offshore investment accounts and use of tax havens

Higher-Risk Sectors

- The tech industry and other highly digitized business models

- Extractive industries

- Various industries reliant on natural resource acquisition and use including food and beverage, apparel, tech sector

- Various industries with operations in countries that are particularly vulnerable to the consequences of low revenue from taxes

- Industries with extensive pollution-generating activities (e.g., pollution of air, water and soil)

Questions for Leaders

- How does the company assess whether its taxation strategy is aligned with, and not undermining, its responsibilities and commitments to respect human rights?

- Does the company publish a tax strategy? Does it disclose the entities it owns, its overall tax rate and the taxes paid where it does business?

- Has the company endorsed the B Team’s Responsible Tax Principles and/or the OECD Tax Guidelines?

- Does the company lobby against taxation/levies (e.g., in the form of carbon emissions taxes, water pollutant discharge fees, waste disposal fees) or make decisions, such as siting operations, based on the (non-) existence of such taxes? If so, does the company include consideration of its human rights responsibilities and commitments when it makes such decisions?

How to use this resource. ( Click on the “+” sign to expand each section. You can use the side menu to return to the full list of red flags, download this Red Flag as a PDF or share this resource. )

Understanding Risks and Opportunities

Risks to People

|

The International Bar Association’s Human Rights Institute (IBA-HRI) found that in the context of the developing world, tax practices considered most relevant to potential human rights impacts include transfer-pricing and other cross-border intra-group transactions (see L Lipsett). Multi-national enterprises may “take advantage of gaps in the interaction of different tax systems to artificially reduce taxable income or shift profits to low-tax jurisdictions in which little or no economic activity is performed” (see OECD). The Tax Justice Network’s State of Tax Justice 2024 report states that multinational enterprises “are shifting on average USD 1.13 trillion worth of profit into tax havens, causing governments around the world to lose USD294 billion per year in direct tax revenue” and that a further USD145 billion in direct tax revenue is lost from offshore wealth tax evasion. In certain jurisdictions and sectors, this type of “offshoring” can be particularly impactful. For example, several large agro-exporters operating in the Ukraine have registered their grain operations in offshore jurisdictions (e.g. Switzerland, Cyprus, British Virgin Islands). The resulting lost tax revenue for Ukraine is estimated to be USD1.2 billion annually from corn alone between 2012–17, instead of being retained in Ukraine to support domestic services, infrastructure or small-scale farmers, thus contributing to rising inequality in the country and acutely impacting the country’s ability to meet basic domestic needs in a time of war. There are also stark examples where loopholes in country tax codes are exploited significantly to minimize corporate tax liability, with important implications for tax revenues. For example, a 2025 study found that in the United States, private equity managers exploit a carried interest loophole by classifying their share of fund profits—typically around 20%—as long-term capital gains rather than ordinary income, thereby significantly reducing their tax liability. This allows them to pay tax rates of around 20% (plus surcharges), instead of the much higher top income tax rates of 37%. Additionally, these managers defer paying taxes on this income until assets are sold, creating a further timing advantage that contributes to a lower effective tax burden compared to wage earners. Combined, these strategies allow private equity executives to cut their effective tax rate nearly in half, depriving the state of important tax revenue and adding to already high levels of wealth inequality that erode political and social stability (see below). These or similar strategies also exist in other jurisdictions, including the UK. Highly digitized business models have also been associated with challenges to existing taxation frameworks, including where the business is highly involved in the economic life of a jurisdiction without any significant physical presence, as well as where a high number of assets are intangible (such as algorithms and software). (See OECD). Aggressive taxation practices such as those identified above can “deprive governments of the resources required to provide the programmes that give effect to economic, social and cultural rights, and to create and strengthen the institutions that uphold civil and political rights.” (See Lipsett). Lost revenue from taxation can lead to decreased funds available for spending on “services such as health, education, housing, access to water and other human rights.” It has been reported that countries in the global south lose much more money to tax evasion and illicit financial flows than they receive in international aid. The Tax Justice Network estimates that lower income countries lose five times as much tax income, as a share of their public health budgets, compared to higher income countries.

To remedy climate-related loss and damage incurred by vulnerable communities globally. Amnesty International and others have called for funding from public sources, “including through taxes and levies for corporations and sectors based on the polluter pays principle.” Another way in which tax and the low carbon transition intersect is with respect to the use of carbon pricing schemes to curb emissions from high-carbon industry. These tax policy approaches are in use in more than 25 jurisdictions globally, and if progressive in their design, can minimize impacts on households while helping to raise revenue for health, education, jobs, low-carbon industries, climate resilient infrastructure and enhancing energy access. These revenues can be used to ensure that the climate transition occurs in a way that respects the rights of workers and communities and serve to “complement, rather than compromise, other efforts of States to fulfill their human rights obligations”. However, corporate lobbying in opposition to this type of taxation has tended to focus on characterizing it as unfair and punitive for workers and consumers regardless of steps taken to minimize regressive impacts. This characterization has, in some instances, helped to undermine both the revenue generation and emissions reduction potential of carbon pricing. Examination of corporate lobbying on tax issues should reflect consideration of the full range of effects on people and not make selective arguments. |

Risks to the Business

-

Reputational Risks:

-

“Over recent years, the tax affairs of major businesses have been subject to unprecedented levels of scrutiny, debate and controversy.” The FT, has noted that despite the “dry, complex nature of corporate tax planning,” campaigners have begun to focus on the issues with “zeal.”

-

In Canada, a Canada Revenue Agency investigation into KPMG’s role in facilitating an offshore tax avoidance scheme to help wealthy individuals avoid taxes, has contributed to ongoing reputational issues for KPMG in Canada, legal challenges, public and professional scrutiny, regulatory penalties and investigations into KPMG’s corporate practices.

-

-

Regulatory Risks: Concerns over the facilitation of base erosion and profit shifting through uneven legislation has led to a multilateral international tax policy initiative under the OECD, resulting in several actions including: a multilateral treaty, the sharing of information between tax administrations, significantly enhanced transparency and exchange of information on tax rulings and annual monitoring and review of harmful tax practices, which has, as of February 2025, resulted in the abolition of 126 tax regimes, with an additional eight in the process of being abolished. International action such as this can be expected to draw regulatory attention across different jurisdictions to aggressive corporate tax practices.

Operational Risks:

-

Public outcry over taxation inequality has

“contributed to significant political instability in many developing countries” which has also been to the detriment of companies operating in these areas. Such outcry has not been limited to developing countries: in the UK several companies have appeared before the Public Accounts Committee or had their high street stores occupied by protestors, and US companies have been the subject of major news investigations. -

Legal, Financial and Operational Risks:

-

In 2024, after several years of legal proceedings, Apple lost its last appeal in the European Court of Justice to avoid paying $14.34 billion (13 billion euro) in back taxes to Ireland, due to “unfair and preferential tax schemes” that it was found to have benefitted from in that jurisdiction.

-

What the UN Guiding Principles say

|

The “corporate responsibility to respect,” the second pillar of the UNGPs, “exists independently of States’ abilities and/or willingness to fulfil their own human rights obligations, and … exists over and above compliance with national laws and regulations protecting human rights.” (Principle 11, Commentary). In other words, “all business enterprises have the same responsibility to respect human rights wherever they operate” (Principle 23, Commentary), whether or not they have a domestic legal obligation to do so. As such, undue or aggressive use of taxation strategies may infringe companies’ responsibility even where actions are legal under local taxation laws. The UNGPs note that companies should “strive for coherence between their responsibility to respect human rights and policies and procedures that govern their wider business activities …” (Principle 16, Commentary), which would be relevant where aggressive tax strategies undermine efforts to respect rights in jurisdictions of operation. Where a company is benefiting from an unduly aggressive tax strategy or unusually generous taxation deal in a particular location, it may be directly linked to impacts that result from a lack of public services for local populations. Where it is aware of this situation and does nothing, it may be judged to contribute to such impacts. This may be a contribution in parallel with other companies benefiting from similar tax arrangements, such that they collectively deplete state revenues needed to fulfil people’s human rights. If the company lobbies in favor of tax deals that undercut state revenues with similar results, it may be seen as contributing by incentivizing the government to favor corporate benefits over the human rights of the population. The connection between taxation planning and human rights is complex, but receiving increased attention. Mauricio Lazala, Deputy Director of the Business and Human Rights Resource Centre has noted that “[t]he State duty to protect human rights in its corporate tax policies, the business responsibility to respect human rights and carry out due diligence in their tax practices, and the need for effective remedy for tax abuse are all relevant, yet still emerging dimensions of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.” |

Possiblr Contributions to the SDGs

Taxation policy is a key element in facilitating the achievement of the SDGs. As such, this red flag indicator is relevant for a range of SDGs, including:

-

SDG 1: No Poverty, including

-

Target 1.2: By 2030, reduce at least by half the proportion of men, women and children of all ages living in poverty in all its dimensions according to national definitions

-

-

SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities, in particular

-

Target 10.4: Adopt policies, especially fiscal, wage and social protection policies, and progressively achieve greater equality. Income redistribution through taxation can contribute to reducing inequality and promoting inclusive growth.

-

-

SDG 13: Climate Action, in particular

-

Target 13.1: Strengthen resilience and adaptive capacity to climate-related disasters

-

Target 13.4: Implement the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change

-

-

SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals, in particular

-

Target 17.1: Strengthen domestic resource mobilization, including through international support to developing countries, to improve domestic capacity for tax and other revenue collection

-

Taking Action

Due Diligence Lines of Inquiry

-

Do we have a policy on tax planning that includes a human rights perspective? Do we have a considered and disclosed position on use of “tax havens”?

-

How transparent are we about our taxation strategy including as regards our operations in developing countries? Do we disclose how our approach to taxation planning aligns with our business purpose and sustainability strategy?

-

To what extent do we review the structures and practices of tax planning through the lens of our responsibility respect human rights, (rather than merely the amount of tax paid, which is an outcome of these practices).

-

Are we involved in projects for which tax rules are being created? Is our approach to these negotiations aligned with our sustainability commitments/ responsibilities?

-

How meaningful is the interaction between our departments and external advisors responsible for taxation strategy and our corporate responsibility/ sustainability/human rights teams, with a view to internal alignment?

Mitigation Examples

* Mitigation examples are current or historical examples for reference, but do not offer insight into their relative maturity or effectiveness.

-

The Fair Tax Mark is a scheme that certifies a business’ tax conduct, including that it “seeks to follow the spirit, as well as the letter of the law, shuns corporate tax avoidance such as the artificial use of tax havens, and is transparent about profits made and taxes paid.”

-

In 2024, the Fair Tax Foundation and CSR Europe teamed up to launch the Tax Responsibility and Transparency Index, which is a benchmark that evaluates company tax performance across five areas: policy and strategy; management and governance; stakeholder engagement; transparency and reporting; and contribution and narrative.

-

Ørsted was the first Danish multinational to receive the Fair Tax Mark and it is a founding member of the Tax Responsibility & Transparency Index. Økonomisk Ugebrev, a Danish financial publication, also ranked it highly in tax transparency, based on their country-by-country reporting, disclosure on tax havens and governance practices.

-

The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) is a coalition of governments, companies and civil society working “to improve openness and accountable management of revenues from natural resources.”

-

Allianz states that it “seeks to be a responsible taxpayer…”. The company reports that it does “not engage in aggressive tax planning or artificial structuring that lacks business purpose or economic substance,” does not use tax havens and “refrain[s] from discretionary tax arrangements.” Allianz has a comprehensive “Standard for Tax Management” which requires that tax planning be based on valid business reasons.

-

A number of companies are annually publishing country by country tax reports to bring greater transparency to their tax activities, including Unilever, BHP and Maersk.

-

In addition to an annual country by country tax report, Danone opines on how its tax practices align with its broader sustainability objectives and discloses its activities in particular jurisdictions that may be perceived as tax havens.

Alternative Models

-

In 2012 Starbucks announced that following “loud and clear” messages from customers, the company would make “changes which will result in Starbucks paying higher corporation tax in the UK – above what is currently required by law”.

-

The 1% for the Planet initiative applies a 1% tax on annual corporate sales, which members commit to donating to grassroots environmental organizations.

-

The Global Green New Deal, which is a declaration signed onto by 300 politicians across 44 jurisdictions, calls for several actions including working together to regulate illicit financial flows, stop capital flight, end tax havens and ensure that world’s biggest corporations and wealthiest people pay their fair share of tax.

Other Tools and Resources

-

The B Team’s Responsible Tax Principles were developed through dialogue with a group of leading companies, convened by The B Team with contributions from civil society, institutional investors and international institution representatives.

-

The Center for Economic and Social Rights has developed a set of Principles for Human Rights in Fiscal Policy, which are derived from international human rights law, including soft law.

-

Tax Justice Network is a UK-based international research and advocacy network focusing on the link between taxation and, inter alia, human rights. It publishes the Corporate Tax Haven Index and has published deep dives into the links between climate justice and tax justice, including specific sectoral analysis for shipping and extractive sectors.

-

The Tax Responsibility and Transparency Index enables multinational businesses to benchmark themselves against high-bar civil society frameworks, pending legislation and pioneering companies in five key areas of tax conduct.

-

The International Bar Association’s Human Rights Institute released a 2013 report entitled Tax Abuses, Poverty and Human Rights. The Report addresses tax abuses from the novel perspective of human rights law and policy. It is based on extensive consultation from diverse perspectives and offers insight into the links between tax abuses, poverty and human rights.

-

The Business and Human Rights Resource Centre portal on Tax Avoidance.

-

Oxfam (2017) Making Tax Vanish: How the practices of consumer goods MNC RB show that the international tax system is broken. Contains an in-depth analysis and critique of the taxation planning practices of one company as well as the company’s response.

-

M Lazala, Business & Human Rights Resource Centre (2015) Tax avoidance: the missing link in business & human rights?

-

The OECD’s Tax portal includes its Action Plan on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting and Inclusive Framework.

Citation of research papers and other resources does not constitute an endorsement by Shift of their conclusions.

Business Model Red Flags

Business Model Red Flags  Tool for Indicator Design

Tool for Indicator Design