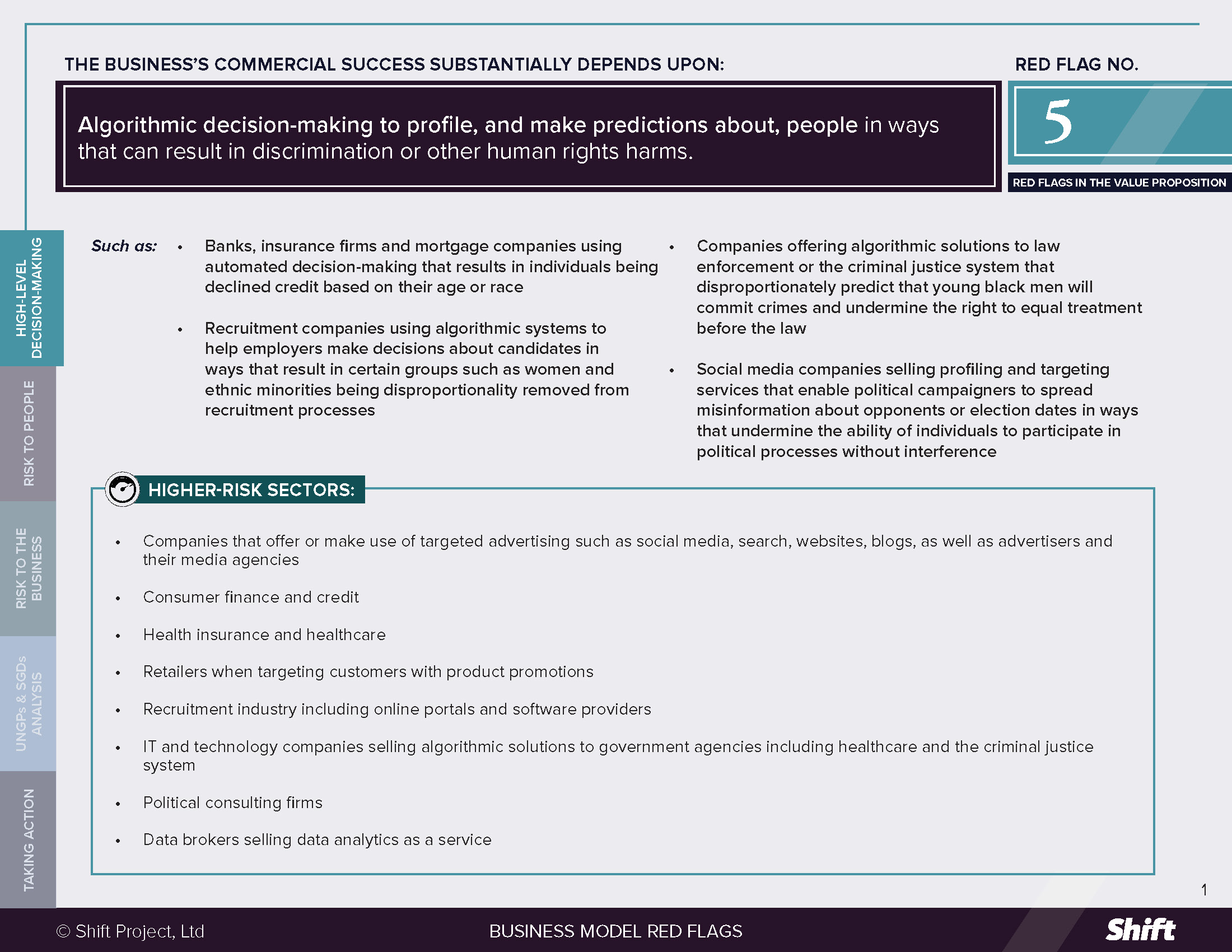

RED FLAG # 5

Algorithmic decision-making to profile, and make predictions about, people in ways that can result in discrimination or other human rights harms.

For Example

- Banks, insurance firms and mortgage companies using automated decision-making that results in individuals being declined credit based on their age or race

- Recruitment companies using algorithmic systems to help employers make decisions about candidates in ways that result in certain groups such as women and ethnic minorities being disproportionality removed from recruitment processes

- Companies offering algorithmic solutions to law enforcement or the criminal justice system that disproportionately predict that young black men will commit crimes and undermine the right to equal treatment before the law

- Social media companies selling profiling and targeting services that enable political campaigners to spread misinformation about opponents or election dates in ways that undermine the ability of individuals to participate in political processes without interference

Higher-Risk Sectors

- Companies that offer or make use of targeted advertising such as social media, search, websites, blogs, as well as advertisers and their media agencies

- Consumer finance and credit

- Health insurance and healthcare

- Retailers when targeting customers with product promotions

- Recruitment industry including online portals and software providers

- IT and technology companies selling algorithmic solutions to government agencies including healthcare and the criminal justice system

- Political consulting firms

- Data brokers selling data analytics as a service

Questions for Leaders

- Do we have evidence that algorithmic profiling delivers notably greater benefits than more traditional tools for decision-making? Have we done an expert review of whether it may lead to us excluding certain groups?

- Do we have in place the necessary technical know-how and oversight to:

- Design, build and deploy algorithmic tools in ways that minimize discriminatory and other risks?

- Responsibly evaluate, procure and use algorithmic tools?

- If challenged, are we prepared to explain the decisions we make using these tools? Can we evidence that we are not negatively impacting people’s right to non-discrimination, privacy and other rights?

How to use this resource. ( Click on the “+” sign to expand each section. You can use the side menu to return to the full list of red flags, download this Red Flag as a PDF or share this resource. )

Understanding Risks and Opportunities

Risks to People

Right to non-discrimination and associated impacts on economic, social and cultural rights, such as housing, employment opportunities, livelihoods and healthcare. The use of algorithms to automate decision-making in industries as diverse as online advertising, recruitment, healthcare, retail, and consumer finance is rarely – if ever – intended to undermine individuals’ right to non- discrimination. In fact, these tools have the potential to reduce or remove human bias from decision-making. Nonetheless, the opposite can also be true. Examples include:

- Social media, search and websites selling targeted advertising where:

- Landlords have been enabled to exclude users based on race, age or gender. This has occurred when tools allowed agents to explicitly exclude certain groups from seeing housing ads. It can also happen in more subtle ways when companies allow targeting based on categories, such as age, marital status, and ZIP code, that are de facto proxies for certain groups. A series of court cases have led to many companies, including Facebook, committing to change their policies.

- Ads for jobs placed on search platforms result in higher paying jobs being shown to more men than women, as in a 2015 case involving Google, reported in the Washington Post. Google has since taken steps to seek to address these, and similar examples, by updating its ad targeting policies.

- Elderly populations have been targeted with fraudulent products or services to trick them out of cash or savings, ranging from anti-ageing products to funeral insurance and reverse mortgages. In one case, retired, politically conservative individuals in the United States were tricked into using much of their retirement savings to buy marked up gold and silver coins to “protect their money from the deep state.” Even though this broke the company’s rules, Facebook showed ads supporting this scheme more than 45 million times over a 21-month period.

- Discrimination in credit and insurance decision-making, for example:

- Where loan providers rely on algorithms to analyze credit worthiness. In 2020, a report from the US-based Student Borrower Protection Center found that two lending institutions were effectively raising the cost of credit for students at academic institutions serving predominantly Hispanic and Black students.

- Where insurance companies use algorithms to set the price of cover. 2018 reports alleged that UK car insurance firms were using algorithms that quoted higher premiums to people with non-Western names. The International Association of Insurance Providers published a paper cautioning the industry about these risks.

- Where individuals’ credit limits are influenced by their social connections. Some companies are requesting mobile phone data and social media records in order to make judgements about credit worthiness. Where individuals’ do not have a credit history this can be one way to positively increase financial inclusion. But is also risks bringing down minorities’ scores if, for example, an individual has friends and family members who have not paid past debts.

- Recruitment industry tools that discriminate. The recruitment industry increasingly integrates automated decision-making as part of its value proposition to employers. In this context, discrimination can occur in a range of ways that have been well highlighted by researchers. High profile examples have included companies offering tools that:

- Examine social media timelines and online postings about candidates with the risk that data which should not legally or ethically exclude an individual from a job – such as political opinion, sexual orientation or having family members convicted of a crime – ends up doing so.

- Use Natural Language Processing to screen out candidate resumes that don’t fit an employer’s prior hiring patterns, which can perpetuate, racial, gender and other discrimination.

- Allow employers conducting video interviews to grade verbal responses, tone, and facial expressions against high- performing employees potentially reinforcing biases and being unable to interpret non-white faces.

- Discrimination in healthcare. Healthcare professionals are increasingly looking to leverage the power of artificial intelligence to achieve breakthroughs in disease detection, diagnosis and patient care plans. The WHO has begun to flag associated ethical risks. In one case, an algorithmic tool sold to hospitals and insurers to predict health care needs was found to underestimate the needs of Black patients.

Impacts on Civil and Political Rights including the right to equality before the law, freedom from arbitrary arrest, freedom of assembly, the right to information, political participation. For example:

- Predictive Policing: In 2019, human rights organizations, journalist and academics reported that police departments in the United States and the United Kingdom were piloting private sector tools to predict crime as a means to allocate resources with discriminating effects based on race, sexuality and age.

- Predicting Recidivism Rates in Criminal Justice: In 2016, A commercial tool developed by U.S company Northpointe to predict the likelihood of a criminal re-offending, was assessed by Pro Publica. Findings included that among other things “black defendants were far more likely than white defendants to be incorrectly judged to be at a higher risk of recidivism, while white defendants were more likely than black defendants to be incorrectly flagged as low risk.”

- Facial Recognition: The proposition of facial recognition tools is to enable users to identify individuals by comparing their facial characteristics against a database of images. Users – such as law enforcement agencies, airports, border control and private security companies – can then act on matches where an individual has committed an offence or that they deem to be a threat. Concerns about these tools include: the risk of false positives and unfair detention (especially where they have proven to be less accurate on non-white and non-male faces), and chilling effects on freedom of assembly.

- Political Campaigning and Disinformation: Social media companies that generate revenue by selling targeted advertising to political campaigners have come under intense scrutiny from civil society organizations making the case that this has threatened democratic processes. Of particular concern have been examples in which voters have been targeted by foreign parties with disinformation about voting dates and processes with the aim of suppressing some voters from going to the polls. Equally concerning, and spotlighted by the infamous Cambridge Analytica scandal, are when political lobby or consulting firms sell micro-targeting strategies using disinformation as a service to political incumbents or opposition parties.

Impacts on the Right to Effective Remedy: Whether algorithmic profiling and predictions amount to State violations, or a business abuse of human rights, the nature of the tools described above can undermine the right to an effective remedy for violations of human rights, which is a fundamental principle of international human rights law. In her 2020 report, the UN Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination and xenophobia explains that, “In many cases, the data, codes and systems responsible for discriminatory and related outcomes are complex and shielded from scrutiny, including by contract and intellectual property laws. In some contexts, not even computer programmers may themselves be able to explain the way that their algorithmic systems function. This “black box” effect makes it difficult for affected groups to overcome steep evidentiary burdens of proof typically required to prove discrimination through legal proceedings, assuming that court processes are even available in the first place.”

Privacy Impacts: Where business models depend on algorithmic profiling and predictions about individuals, this can create or compound risks to the right to privacy. For example:

- By revealing details about an individual’s private life against their will. In 2012, U-S retailer Target was criticized for posting coupons for baby products to the household email account used by a teenage girl, thereby alerting her father to the fact of her pregnancy. The company’s predictive analytics tools had deciphered that the girl was pregnant based on her recent purchase history. Some individuals have reported that adverts clearly targeting members of the LGBTQ community have appeared on their newsfeed in sight of family members or colleagues, resulting in the individual feeling outed.

- By incentivizing “data maximization.” Algorithms need ton e trained on vast amounts of training data concerning the personal habits, preferences and behaviors of individuals. This may incentivize developers and engineers building algorithmic systems to collect or source data without putting in place privacy-protecting processes e.g. around consent.

Risks to the Business

- Rapidly Evolving Regulatory Risks: The development, sale and use of algorithmic profiling and decision-making tools is gaining increased attention from regulators. In the United States there have been proposals for a federal Algorithmic Accountability Act and local law makers have already passed (New York City in 2017) or are debating laws (for example, Washington State). The most notable developments have taken place in the European Union.

- The EU’s General Data Protection Regulation addresses

the right of individuals not to be data subject to a decision based solely on automated processing, including profiling, where that decision has legal or other effects concerning him or her or similarly significantly affects them. In one example, a Swedish financial services company was ordered to correct its credit risk algorithm which was illegally using age as a parameter to determine credit. The EU Competition Commissioner has announced plans to further regulate this practice.”

- The EU’s General Data Protection Regulation addresses

- Existing Legal Risk: Where algorithms are being designed and used to make traditional decisions in novel ways concerning employment, advertising and credit, existing laws apply. For example:

- The use of AI in hiring in the United States may lead to companies failing to comply with existing laws such as the Employee Polygraph Protection Act or Genetic Information Non Discrimination Act.

- The American Civil Liberties Union brought a series of cases against Facebook and the U.S Department of Housing also filed charges alleging that its algorithm violated US Equal Employment Opportunities laws and the US Fair Housing Act. Facebook settled in both cases, and has changed their policies and systems.

- In the UK, law firms and academic institutions have warned that financial institutions that make use of algorithms can risk non-compliance with consumer lending laws.

- Reputational Risk, Including with Employees: The sharp increase in civil society scrutiny of algorithmic tools means that companies developing or using such tools may experience reduced trust from consumers, employees and citizens. In 2019, 250 Facebook staff members published a letter criticizing the company’s refusal to fact-check political ads and tied the issue to ad targeting.

- Lost Investment Pre-Launch: Where companies using algorithms are found to discriminate or are deemed to be making decisions in ways that lack a social license, this can result in companies having to choose not to take these products to market. In 2018, one company had to halt the launch of a product designed to vet people for domestic services using “advanced artificial intelligence” to analyze their personalities based on social media posts, after they faced a public backlash.

What the UN Guiding principles say

*For an explanation of how companies can be involved in human rights impacts, and their related responsibilities, see here.

Companies that make decisions and pursue actions based on algorithmic profiling and predictions can cause adverse impacts on human rights. An example would be a bank denying credit based on a tool that makes discriminatory recommendations.

Companies whose value proposition is to sell the capability to profile and predict to public or private third parties can contribute to adverse human rights impacts that those actors cause where their tools embed discriminatory biases. Contribution might arise due to the ways that customers are empowered to use these tools (such as by excluding certain groups) or may be more subtle such as when an algorithmic system has bias built into the data set.

An added complexity is that a single algorithmic system may integrate a number of inputs from different actors. For example, a data broker might provide training data; an AI research firm might license an algorithm and a developer might design the customer interface. Depending on the specific circumstances, each of these companies could contribute to adverse impacts.

In situations where companies have taken reasonable steps to prevent their tools contributing to discrimination and other human rights harms, they may nevertheless be linked to adverse impacts that business or government customers are causing.

Possible Contributions to the SDGs

Algorithmic systems may be used to advance a number of SDGs such as those listed below. Addressing impacts to people associated with this red flag can contribute to ensuring that this is done in ways that do not simultaneously impact people’s rights to non-discrimination, privacy and physical and mental health and well-being.

SDG10: Reduce Inequality within and Among Countries.

SDG3: Healthy Lives and Well-Being for all, including by tackling disruptions to progress such as from the COVID-19 global pandemic.

SDG 5.B: Promote Empowerment of Women Through Technology

SDG11: Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient

The UN Secretary-General’s Roadmap for Digital Cooperation is an important resource to guide “all stakeholders to play a role in advancing a safer, more equitable digital world” even as technological solutions are used to achieve the SDGs.

Taking Action

Due Diligence Lines of Inquiry

Unless otherwise indicated, the following questions draw heavily on Ranking Digital Rights’ Best Practices: Algorithms, Machine Learning and Automated Decision-Making, and the World Economic Forum’s White Paper on How to Prevent Discriminatory Outcomes in Machine Learning.

- Do we have a clear policy that describes how the company identifies and manages human rights risks related to the algorithmic system(s) we use?

- Do we inform customers or users about the existence of algorithmic profiling, describe how this works, explain the variables that influence the algorithm, and explain how users and customers may be impacted?

- Have we mapped and understood if any particular groups may be at an advantage or disadvantage in the context in which the system is being deployed? Do we have a method for checking if the output from an algorithm is decorrelated from protected or sensitive features?

- Do we seek a diversity of views about the potential risks of proposed models, especially from specific populations affected by the outcomes of algorithmic systems we use?

- Have we established robust diversity and inclusion policies at every level of the company, and notably in teams that develop algorithms, machine learning models, or other automated decision-making tools?

- Have we consulted with all the relevant domain experts whose interdisciplinary insights allow us to understand potential sources of bias or unfairness, and to design ways to counteract them?

- Do we assess whether any uses or use-cases of our algorithmic tools pose risks to human rights? Where we identify these, are we:

- Creating clear and enforceable terms of use?

- Engaging enterprise and government customers/users to educate and train them about how to use the tools without increasing human rights risks?

- Do we have systems in place to monitor and review how customers are using our tools?

- Are we clear about the actions we will take if we discover that our tools are being used in ways that lead to, or increase the likelihood of, adverse human rights impacts?

- Do we apply “rigorous pre-release trials to ensure that algorithmic systems will not amplify biases and error due to any issues with the training data, algorithms, or other elements of system design?”

- Have we outlined an ongoing system for evaluating fairness throughout the life cycle of our product? Do we have an escalation/emergency procedure to correct unforeseen cases of unfairness when we uncover them?

- Are we clearly committed to only buying and/or using training datasets that comprise data whose data subjects have provided informed content to having their data included in datasets used for this purpose?

- Are we making dataset(s) used to train machine learning models, terms of use, and APIs available to allow third parties to provide and review the behavior of our system?

- What reporting, grievance or redress processes and recourse do we have in place? Do we have a process in place to make necessary fixes to the design of the system based on reported issues or concerns?

Mitigation Examples

Mitigation examples are current or historical examples for reference, but do not offer insight into their relative maturity or effectiveness. Moreover, some examples listed below are proposals for mitigating actions that have come from data science and engineering research institutes.

- Principles, Governance and Oversight: A number of companies in the technology industry and beyond have committed to some form of AI fairness principles as well as having ethics officers and cross-functional committees that look at these issues. One example is Microsoft’s AI, Ethics and Effects of Engineering and Research (AETHER) Committee, which operates alongside the company’s Office of Responsible AI (ORA). Microsoft states that its governance arrangements are designed to set “company-wide rules for enacting responsible AI, as well as defining roles and responsibilities for teams involved in this effort” and that “senior leadership relies on Aether to make recommendations on responsible AI issues, technologies, processes, and best practices.”

- Tech Tools to Detect Bias: Some technology companies – including IBM, Microsoft, Google’s What-If tool and Facebook’s Fairness Flow – have developed products aimed at detecting bias in algorithmic decision-making. Such efforts can be a way to root-out bias from companies’ own profiling and predictive models as well as a way for “big tech” to mitigate the risk that third parties develop, design and deploy discriminatory algorithms using these companies’ platforms or computing power. With a similar purpose, Aequitas is an “an open source bias audit toolkit developed at the University of Chicago, [that] can be used to audit the predictions of machine learning based risk assessment tools to understand different types of biases, and make informed decisions about developing and deploying such systems.”

- Debiasing Discrimination in Lending: Start-up Zest AI has created a feature that “uses a technique called adversarial debiasing to correct discrimination in lending models… One model predicts a borrower’s ability to pay, while the second predicts protected information, such as the race or gender of the borrower. The dueling models learn from each other through dozens of adjustments until the discrimination predictor is stumped — the race or gender variable bears no meaningful relationship to the applicant’s credit score.”

- Data-sheets for Data Sets: Experts at Microsoft Research have proposed the idea of labelling of data sets that train algorithms similar to a nutrition labelling on foods. The intent would be to mitigate against discriminatory outcomes that occur when biased data sets are used to train algorithmic models. The idea is that this will “allow users to understand the strengths and limitations of the data that they’re using and guard against issues such as bias and overfitting.”

- Changes to Targeted Advertising Policies: As far back as 2015, Facebook and Google banned payday loan companies from advertising on their platforms. Since 2019, Twitter, Google and Facebook have made changes to the policies and systems that allow customers to target adverts. Different changes pertain to different categories of advert including for housing and job opportunities. Of particular interest from a human rights perspective were the changes that Twitter and Google made to policies concerning political advertising made in the run-up to the 2020 US presidential election. Twitter banned political ads outright in October 2019. Google limits targeting advertising in certain broad categories such as sex, gender and postcode (as against micro-targeting). The exact impact of these moves, including from a human rights perspective, is still being explored.

- LinkedIn Fairness Tool Kit: Linked-In has developed LiFT an open-source project that detects, measures, and mitigates biases in training data sets and algorithms. The company has been using the tool itself to “compute the fairness metrics of training datasets on its platforms, such as the Job Search model.”

- Ideal’s Reduce-Bias Guidance and tool to Reduce Bias: The recruitment services firm Ideal published a Workplace Diversity Through Recruitment: A Step-By-Step Guide and has a tool that customers can use to test and monitor for adverse impacts in its candidate grading system. Customers who collect demographic data during the course of their hiring process, can ask Ideal to instruct its algorithms to both ignore those demographics and test for and remove adverse impacts based on, among other things, compliance with the US Department of Labor’s affirmative action program, Canada’s equity programs for designated groups, and the European Union’s hiring discrimination laws.

Other tools and resources

- Racial Discrimination and Emerging Digital Technologies: A Human Rights Analysis (A/HRC/44/57), Report from the UN Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism.

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (2018) Big Data: Discrimination in data-supported decision making.

- Harvard School of Law and Corporate Governance Artificial Intelligence and Ethics: An Emerging Area of Board Oversight Responsibility.

- UK Information Commissioners Office GDPR: Rights Related to Automated Decision-Making including Profiling.

- UN Secretary-General’s Roadmap for Digital Cooperation.

Citation of research papers and other resources does not constitute an endorsement by Shift of their conclusions.

Business Model Red Flags

Business Model Red Flags  Tool for Indicator Design

Tool for Indicator Design