Land Rights

Land is life. Regardless of geographical location and socioeconomic status, each person relies on land, at least to some degree, for the provision of basic human needs such as clean water to drink, nutritious food to eat, and safe housing to shelter in.

In many cases, the planet’s most vulnerable populations also directly rely on land in farming, hunting, gathering and carrying out other tasks for daily subsistence and in maintaining their and their families’ livelihoods and cultural identities.

Almost 75% of the world’s poor are affected directly by land degradation.

Business activities can have a wide range of impacts on people in relation to land. According to the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, “[a]n increasing number of people are forcibly evicted or displaced from their land to make way for large-scale development or business projects, such as dams, mines, oil and gas installations or ports.” What’s more, “[i]n many countries the shift to large-scale farming has also led to forced evictions, displacements and local food insecurity, which in turn has contributed to an increase in rural to urban migration and consequently further pressure on access to urban land and housing.”

Land quality is closely linked to a healthy environment and sustainable access to natural resources. As such, land degradation connected to private sector activities can have significantly negative and widespread effects on people, for instance due to higher levels of water and air pollution or lack of access to firewood and other essential energy sources.

Access to, use of and control over land directly affect people’s enjoyment of their human rights. For example, “[f]or many people, land is a source of livelihood, and is central to economic rights. Land is also often linked to peoples’ identities, and so is tied to social and cultural rights.” Moreover, “the human rights aspects of land affect a range of issues including poverty reduction and development, peacebuilding, humanitarian assistance, disaster prevention and recovery, urban and rural planning, to name but a few. Emerging global issues, such as food insecurity, climate change and rapid urbanization, have also refocused attention on how land is being used, controlled and managed by States and private actors.”

Approximately 1.6 billion people depend on forests for their livelihoods, including around 70 million indigenous people.

Under the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), land-related human rights issues are of particular concern in the context of business impacts on indigenous populations. For instance, UNDRIP and other frameworks such as the International Finance Corporation (IFC) Performance Standards require the free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) of indigenous peoples for business activities that pose actual or potential impacts on their land and associated human rights.

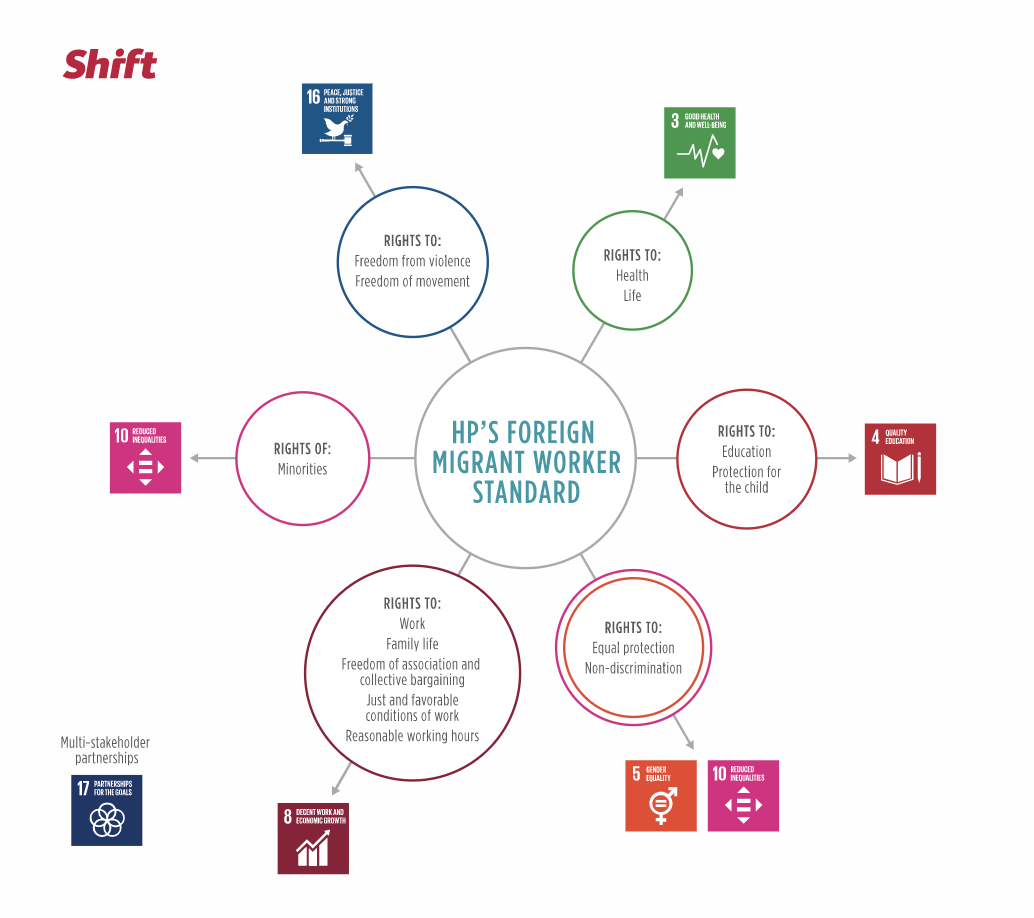

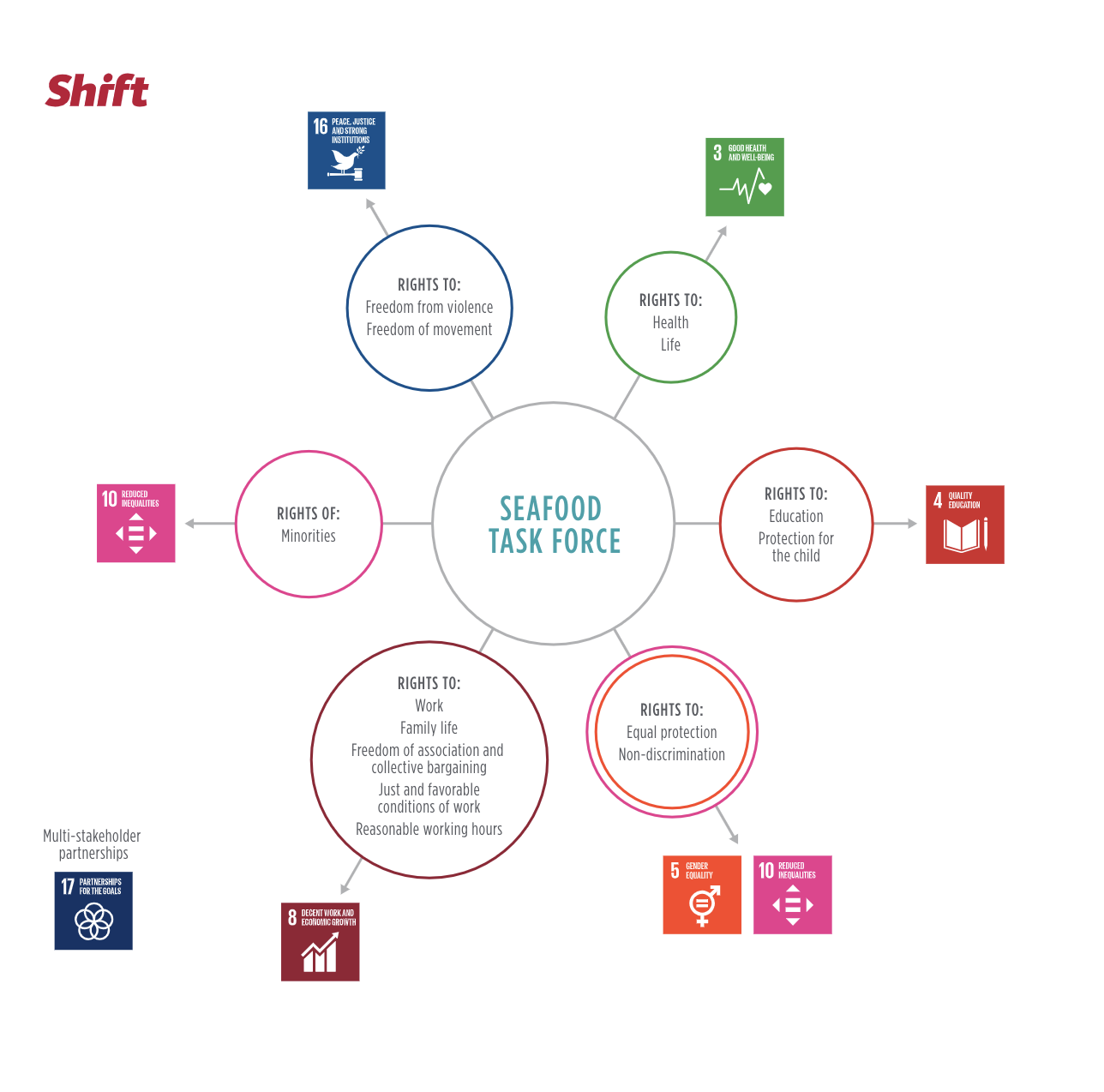

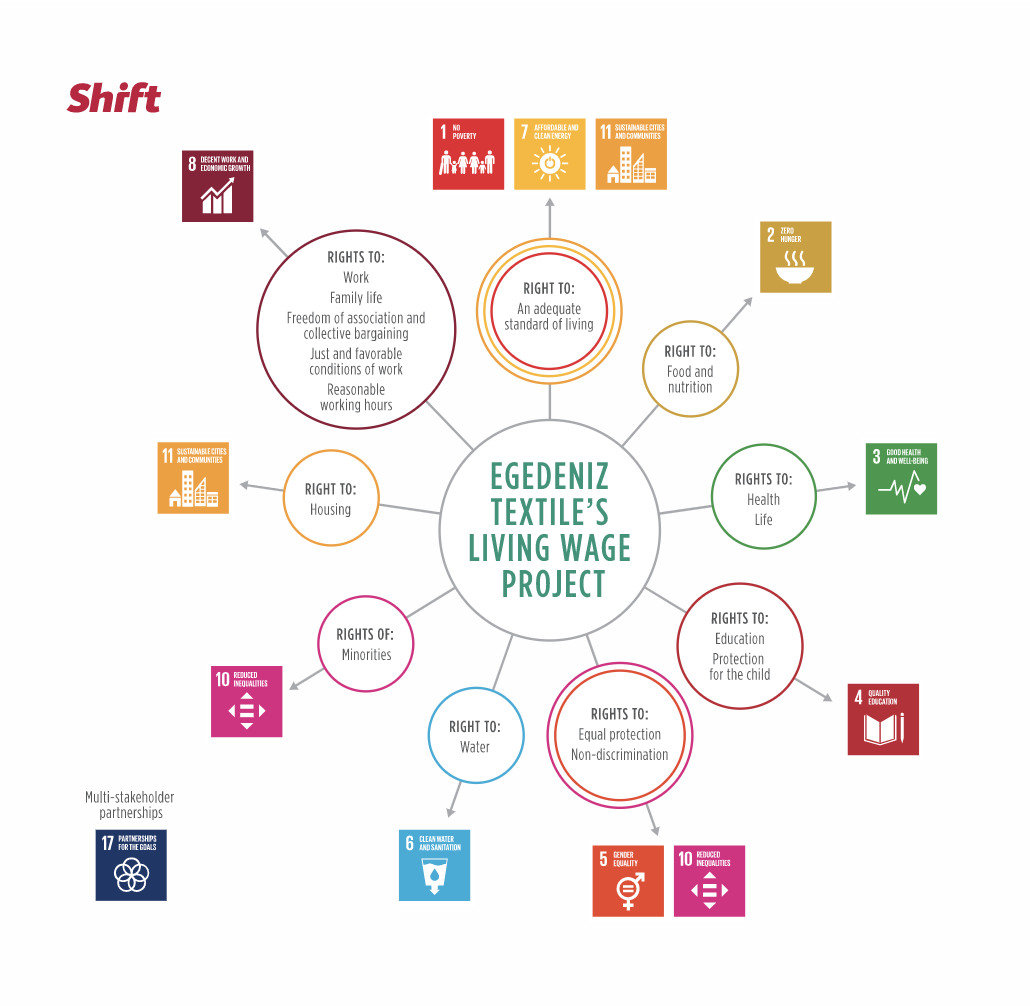

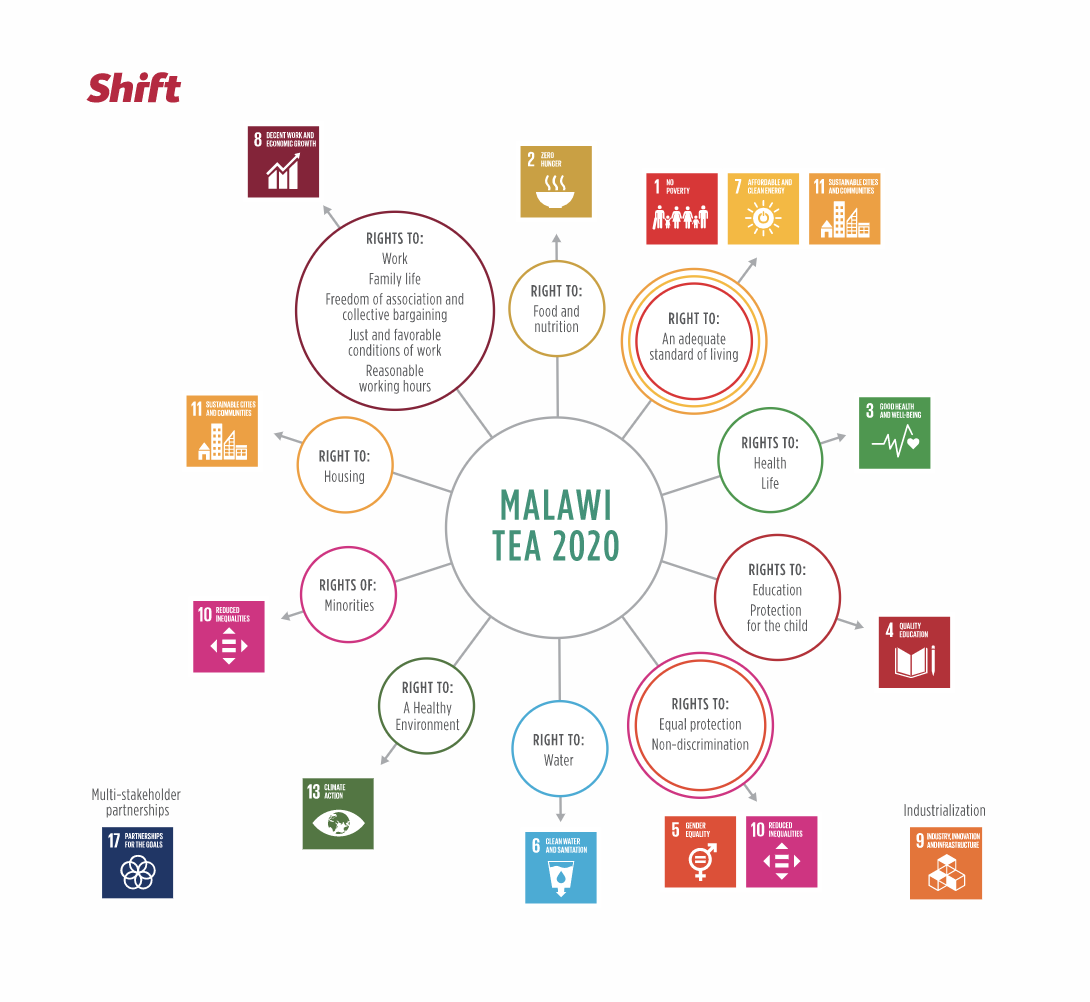

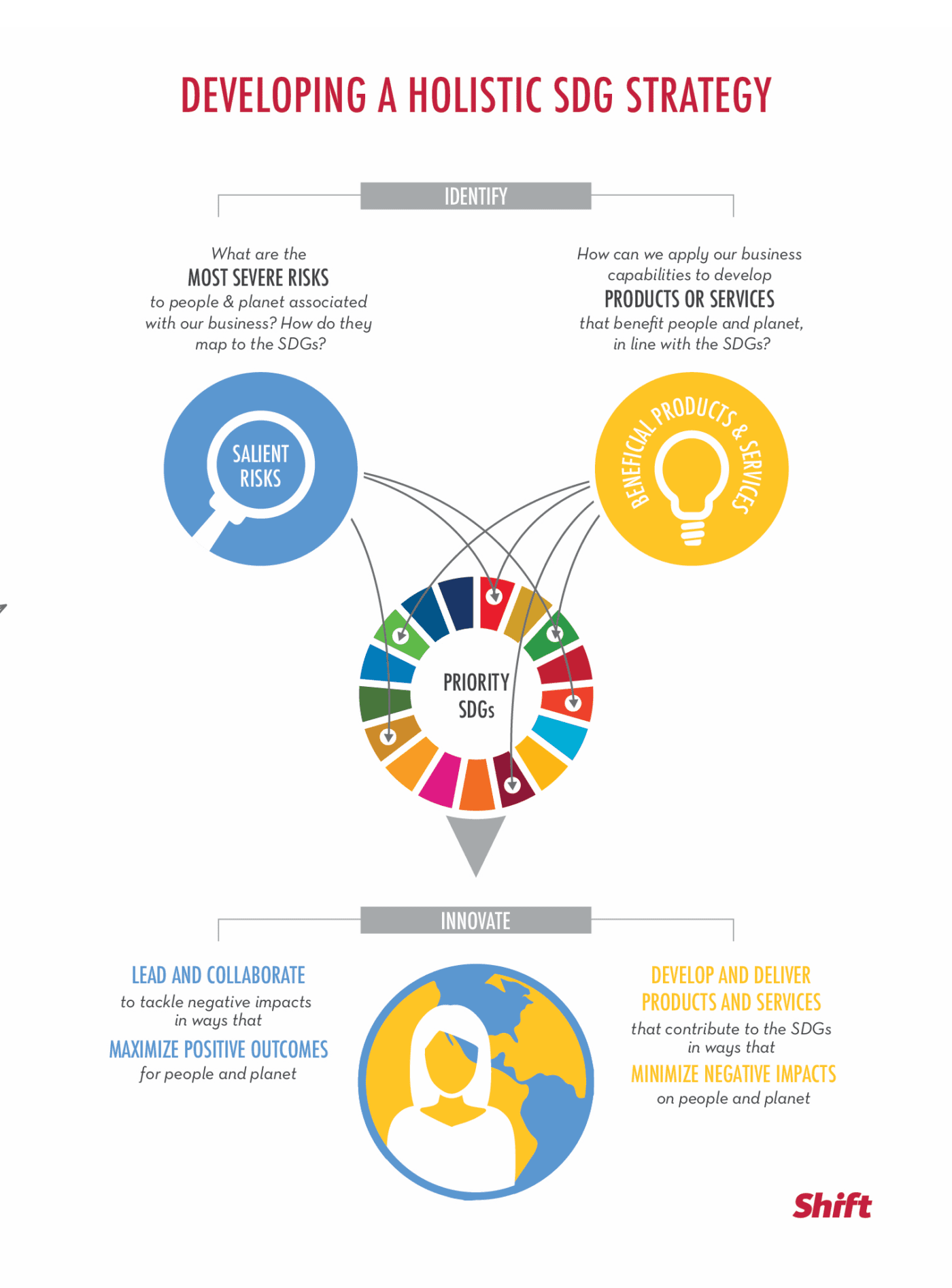

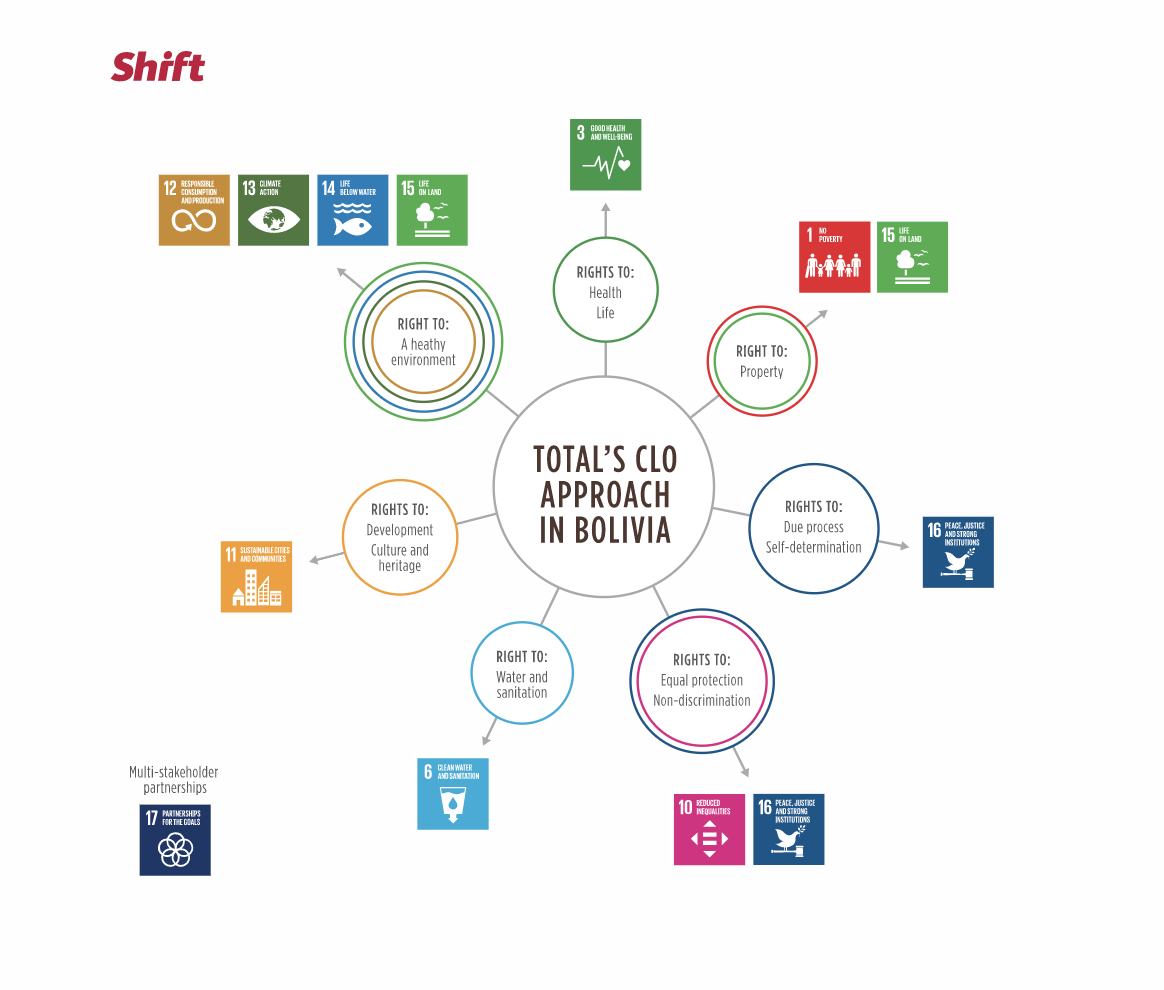

As illustrated above, and depending on the specifics of the relevant corporate initiative, addressing land rights in the context of business activities may contribute to the achievement of an array of the Global Goals, including:

- Goal 1: End poverty in all its forms everywhere[i]

- Goal 2: End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture[ii]

- Goal 3: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages[iii]

- Goal 5: Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls[iv]

- Goal 6: Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all[v]

- Goal 8: Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all[vi]

- Goal 10: Reduce inequality within and among countries[vii]

- Goal 11: Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable[viii]

- Goal 12: Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns[ix]

- Goal 13: Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts[x]

- Goal 14: Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development[xi]

- Goal 15: Protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss[xii]

- Goal 16: Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels[xiii]

So, how are companies currently supporting a world in which these goals can become a reality – a world in which land-related human rights are respected across all areas of business activity?

Examples illustrated by the case studies below include:

- Mining companies operating in the same region are engaging in similar initiatives around stakeholder engagement: Three diamond mines in the Northwest Territories of Canada are linked to independent monitoring agencies set up to protect the environmental and land rights of affected Aboriginal groups at all stages of the mines’ life cycles.

- A large buyer of a high-risk commodity is partnering with an international civil society organization: A global food and beverage brand is participating in a new model for socially and environmentally sustainable palm oil production that focuses on participatory and inclusive land-use planning and development.

- An oil and gas company is working with trained community members to support early-stage dialogue with indigenous populations: An extractives exploration project in Bolivia is working with community liaison officers to implement proactive engagement strategies with local indigenous populations based on past experiences and key lessons learned.

These case studies explore each of these innovative and evolving models in more detail. Each case study captures publicly available information on the initiative, alongside experiences and opinions from various actors involved.

The summaries do not claim to give a definitive account of a specific initiative or of all perspectives on that case study; instead, they are intended to serve as illustrative examples of how action toward corporate respect for human rights can make a critical contribution to the achievement of various goals and targets under the SDGs.

Key Takeaways on Land Rights

Individual Company Action

Individual Company Action

- Legally binding agreements between the company, affected rights-holders, and relevant government authorities can provide clear parameters, valuable oversight mechanisms and robust accountability structures that aid in ensuring respect for land-related human rights.

- A willingness to participate in new multi-stakeholder models can complement existing initiatives, address important gaps in current implementation efforts and place a company at the forefront of innovative efforts.

- Working hand-in-hand with community representatives in formalized ways can bridge cultural and other contextual gaps when it comes to local engagement and relationship building around sensitive issues such as land rights.

- Affected stakeholders may require support in order to effectively and meaningfully engage in consultation processes that are required or otherwise necessary to address land-related risks and impacts. Depending on context, such support might be in the form of financial resources, formal employment or expert guidance, and it may come from business where there is openness from stakeholders.

- Prioritizing meaningful stakeholder engagement early and often can assist a company in avoiding any escalation of land-related conflicts or other challenges throughout the lifespan of a project. This may include early land tenure diagnoses to enhance the company’s understanding of land rights in the project area before entering into easements or purchases.

De Beers and the Snap Lake Environmental Monitoring Agency

Supporting community-based oversight bodies to address Aboriginal rights

The challenge

The Northwest Territories (NWT) province in Canada is one of two jurisdictions in the country where Aboriginal peoples are in the majority, constituting slightly more than 50% of the population. The region’s geographical resources include diamonds, gold, natural gas and petroleum, all of which have attracted extractive companies to the area since the early 1900s.

While the mining and oil and gas industries have brought economic growth and job opportunities to the NWT at various stages, significant challenges have arisen in terms of preserving the land and natural resource rights of the Aboriginal population throughout the course of business activities.

“When we talk about ‘Land’ in the Northwest Territories, it’s with a capital ‘L.’ Land here means more than just actual territory. It’s about wildlife, water, air quality, entire ecosystems, and livelihoods for the people who live on that land. All of this depends on the integrity of the land; and there are deep cultural connections to the natural resources connected to both the land and the environment.”

Alex Power, Yellowknives Dene First Nation

The response

Under the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), land-related human rights issues are of particular concern in the context of business impacts on indigenous populations. In this context, three diamond mines in the NWT have taken a distinct approach in understanding and managing risks to surrounding communities when it comes to land and the environment in connection with mining operations. The licensing and registration process for each mine has involved legally binding environmental agreements between the respective diamond company, the federal government, the NWT government, and affected Aboriginal groups in the area.

Each agreement requires the establishment of a community-based, independent environmental monitoring agency (EMA) to study potential and actual environmental impacts, including those that relate to impacts on people, and facilitate activities around the free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) of Aboriginal groups in relation to each mine. Each EMA acts as a public watchdog organization to ensure environmental regulatory compliance by the mining company and oversee inspection processes by government regulators.

The three EMAs in the NWT include: (1) the Independent Environmental Monitoring Agency (IEMA), covering Dominion Diamond Ekati Corporation’s Ekati mine; (2) the Environmental Monitoring Advisory Board (EMAB), covering Diavik Diamond Mines’ Diavik mine; and (3) the Snap Lake Environmental Monitoring Agency (SLEMA), covering De Beers Mining Canada’s Snap Lake mine. All three agencies facilitate multi-stakeholder dialogue and engagement across Aboriginal, company and government actors.

“Our approach is to engage early and often with potentially affected communities, going beyond the minimum requirements of the law to capture issues and concerns that aren’t yet fully addressed in legislation. We also share learnings from our experiences with SLEMA across the whole of the organization, integrating a better understanding of these issues across procurement, human resources, senior management and other functions.”

– ALEXANDRA HOOD, DE BEERS MINING CANADA

Key aspects of the initiative

As an example of the EMA approach to addressing land-related human rights risks to Aboriginal groups associated with mining activities, De Beers and the work of SLEMA involves the following components and activities to date:

- Secretariat with an Executive Director and an Environmental Analyst. Led by the Secretariat, the agency is charged with: “(1) Reviewing and commenting on the design of monitoring and management plans and the results of these activities; (2) Monitoring and encouraging the integration of traditional knowledge of the nearby Aboriginal peoples into the mine’s environmental plans; (3) Acting as an intervener in regulatory processes directly related to environmental matters involving the Snap Lake Project and its cumulative effects; (4) Bringing concerns of the Aboriginal peoples and the general public to De Beers Canada Mining Inc. and the government; (5) Keeping Aboriginal peoples and the public informed about Agency activities and findings; and (6) Writing an Annual Report with recommendations that require the response of De Beers Canada Mining Inc. and/or government.”

“De Beers has been very proactive in its engagement with SLEMA. Our assessment is that they want to do a good job and have this be a positive case study that they can learn from. They’re quite focused on engagement and want the project to be wrapped up nicely. They place particular importance on the role of SLEMA in bringing traditional knowledge into the picture and incorporating this information in the company’s decision-making processes.

De Beers and other companies must understand that, if they want to do business in these types of regions, they have to do it in collaboration with the impacted communities. The SLEMA model is a smart approach that should be replicated, synchronized, adequately resourced and shared wherever possible.”

Philippe di Pizzo, Executive Director, SLEMA

- Agency board comprised of eight representatives from the four signatory Aboriginal groups, including the Tli Cho Government, Lutsel k’e Dene First Nation, Yellowknives Dene First Nation, and the North Slave Metis Alliance. The board “strives to involve Aboriginal traditional knowledge and conventional science in its assessment of mining activities and environmental reports submitted by De Beers and government inspectors.”

- Technical panel made up of scientific experts who are familiar with the NWT and who have reviewed the mine’s annual reports, wildlife monitoring program, Aquatic Effects Monitoring Program Design Plan, and the Interim Closure and Reclamation Plan.

- Traditional Knowledge (TK) panel comprised of Elders from the affected Aboriginal groups that have hunted, trapped and lived in the area of the mine site. The TK panel provides “advice on water and fisheries issues and wildlife and habitat issues.” The group has a particular focus on the mine’s current closure activities and on ensuring that this stage of the project is monitored for the long-term stability of the land once the company leaves.

“It is incredibly important to have an independent oversight body for these types of business projects, where surrounding communities are impacted in numerous ways. It’s really key for Aboriginal groups to have an expert body to go to, because we’re under-resourced, particularly where multiple projects require our consultation and participation. These oversight bodies also carry a lot of weight in terms of credibility as they are directed by multiple groups, maintain full independence and blend scientific and traditional knowledge.”

– ALEX POWER, YELLOWKNIVES DENE FIRST NATION

PepsiCo’s Participation in Oxfam’s FAIR Company-Community Partnerships

Piloting new models to address risks to land rights in the palm oil industry

The challenge

Palm oil is the most widely consumed vegetable oil on the planet, with global use more than doubling over the past 15 years. Currently contained in approximately half of all consumer goods, this high-yielding agricultural commodity is found in packaged foods like margarine, ice cream and chocolate, as well as non-food products like body lotion, soap and biofuel.

The production of palm oil, while highly efficient as compared to all other oil crops, requires considerable swaths of land to be cleared for palm nurseries and plantations. Industry analysts have estimated that, in order to meet projected demand growth, global palm oil production “will need additional land that would be equivalent to the total area of Bangladesh” by 2050.

Land expansion is therefore key to the sector’s ability to keep up with this rapid increase in global demand. As a result, businesses along palm oil supply chains have long faced significant public criticism around the industry’s contributions to deforestation, biodiversity loss, climate change and other environmental impacts. The sector has also been linked to significant human rights violations related to communities’ land and natural resource rights, food insecurity and land conflict. More recently, the production and processing of palm oil has been connected to reports of child labor, forced labor and other labor-related impacts.

With the aim of improving environmental and social sustainability in the industry, various palm industry stakeholders came together to form the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) in 2004. The RSPO’s primary mechanism in working to achieve this goal is “a set of environmental and social criteria which companies must comply with in order to produce Certified Sustainable Palm Oil.” With the immense amount of land involved in palm oil production, the RSPO’s focus thus far has been on certification among large-scale producers. At the same time, a significant amount of the sector’s land use is among smallholder farmers whom current certification mechanisms do not often reach and where risks to people and the environment are often among the most severe.

“The main issues linked to the palm oil sector are connected to the industry’s rapid growth, which requires additional land. The key risks and impacts are therefore around deforestation and greenhouse gas emissions, but also around land grabs and land degradation, both of which directly impact people.

There is a particular lack of visibility around these issues when it comes to smallholders, who are bringing land assets to out-grower schemes that often fail to take an inclusive approach with smallholders and communities. These long-standing palm oil models are therefore characterized by exploitation and vast changes in land use without adequate social and environmental protections in place.”

– JOHAN VERBURG, OXFAM NOVIB

The response

As a significant buyer of palm oil, PepsiCo is an important actor in addressing land-related human rights issues in the industry. The global food and beverage company has identified land rights as one of its salient human rights issues – the human rights at risk of the most severe impacts in the company’s operations and supply chains. PepsiCo’s salient human rights issues also include land-related issues such as the human right to water and vulnerable workers such as women.

A key milestone in PepsiCo’s approach to the sustainable sourcing of palm oil was its 2014 commitment to “zero tolerance” for land grabs across its supply chains following Oxfam’s Behind the Brands campaign and associated advocacy efforts. In the past year, PepsiCo has also made a number of time-bound implementation plans regarding its land rights commitments in Brazil, Mexico, Thailand and Indonesia.

As the largest buyer of palm oil in Mexico, the company has published a detailed analysis of land tenure risks and impacts and is now carrying out training on high conservation value (HCV) and high carbon stock (HCS) assessments, as well as separate capacity-building programs with the national association of palm oil mills and producers, smallholders and the federal government.

As part of these ongoing efforts, PepsiCo made a commitment in February 2018 to participate in Oxfam’s FAIR Company-Community Partnerships, which “offer an alternative business model that addresses sustainability issues holistically, ensuring respect for human rights, protection of the environment, and inclusive economic development through a multi-stakeholder, landscape-based approach.”

With an initial focus on Indonesia in its work with PepsiCo, the FAIR Partnerships project and its acronym stand for: (1) Freedom of choice, including free, prior and informed consent; (2) Accountability, including transparent agreements and grievance mechanisms; (3) Improvement and sharing of benefits, including improved yields and resource use efficiency; and (4) Respect for rights and the environment.

“When individuals and communities understand their rights regarding land and land tenure, it contributes to them being in a secure position where they are better able to claim the full range of their other human rights.We know that the challenges and issues in palm are systemic and we can’t change them alone. We need to collaborate with others, and the FAIR Partnerships project’s role as a multi-stakeholder platform is key in this regard.This is about further developing smallholder farmers and women, protecting the environment, and implementing our commitments on land rights. We’re building on our experience and learning in other sectors and geographies to maximize positive outcomes for people with this project.”

Natasha Schwarzbach, PepsiCo

Key aspects of the initiative

The FAIR Company-Community Partnerships “require the active participation of multiple global and national companies in the palm oil value chain, local government agencies, civil society groups, and farmer organizations.” Following the development of its conceptual model in 2014, the initiative was co-created with sector stakeholders for two demonstration projects that began initial field-level activities in 2017. As the project is taken to scale, it will reach multiple locations in Indonesia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Nigeria.

PepsiCo is the first buyer to publicly support the FAIR Company-Community Partnerships. In addition, the initiative has “engaged with numerous commodity sector and financial sector companies” including “plantation and mill companies, consumer goods manufacturers, commercial and development banks, and institutional and impact investors.” In these engagements, the project’s approach is to “collaborate with buyers and investors to engage and support palm oil producers who, in turn, engage smallholder suppliers and their host communities.”

“The FAIR Partnerships project is rethinking the ‘business as usual’ growth model for palm oil production, processing, and trade. It’s taking a holistic approach that zooms in on company-community relations to more effectively include smallholders and impacted communities in land use planning and development.The businesses involved, including PepsiCo, are key ambassadors for this new model as it builds on other collective, multi-stakeholder efforts such as RSPO. Our goal in the long term is to move from commitments around what you should not be doing as a company, for instance ‘zero tolerance’ for land grabs and other human rights violations, to alternative models that are more positive and focused on implementation.”

– JOHAN VERBURG, OXFAM NOVIB

While the project remains in the early stages of implementation, the initiative is currently focused on demonstration projects that can then be scaled up based on “the proven business case, lessons learned, and impact measured.” The main components of these demonstration projects will include:

- Participatory mapping and land use planning to “establish multi-functional mosaic landscapes in which stakeholders … arrive at optimal combinations of export crops such as palm oil, local food crops and conservation areas, notably forest and peat land” in order to enhance food security, safeguard land rights and diversify incomes. Local government authorities will be invited to support this landscape approach.

- Direct engagement from palm oil companies to their host communities and small producers “at an early stage, when a company and host community start to (re-)consider relationships in palm oil production, especially at the moment of new plantings or replanting.”

- Capacity building with local civil society organizations, service providers and government actors, as well as environmental organizations and other relevant platforms in order to align, and not duplicate, efforts.

- Engagement with commodity markets and capital markets, which aim to “execut[e] their sustainable palm oil policies and [meet] sustainability objectives, notably taking deforestation out of their value chains and ensuring smallholder inclusion.”

- Monitoring, evaluation and learning systems that build out data collection methods and guide joint learning.

“FAIR Company-Community Partnerships bring together a wide range of salient human rights issues in the palm oil industry, providing an avenue for companies to address their most severe impacts more holistically. Implementation of commitments around land rights and corporate respect for human rights takes time and resources, but PepsiCo has taken an important step in committing to this project. The lessons they learn through their involvement will be valuable not only to PepsiCo but to wider industry efforts.”

Chloe Christman Cole, Oxfam America

Total’s Community Liaison Officer Approach to Dialogue with Indigenous Groups in Bolivia

Going beyond compliance to engage rights-holders early and often

The challenge

Land rights and land tenure issues have a particularly complex history in Bolivia. Rich in gas reserves, the landlocked country in western-central South America has undergone various stages of political turmoil due in no small part to conflict over who controls these natural resources and associated landholdings.

Since 2003, Total Exploration and Production Bolivia (TEPBO), a wholly-owned subsidiary of French oil and gas company Total, has explored natural gas projects in Bolivia’s eastern lowlands, where several Guaraní indigenous territories are located.

“The operations in our business units may require land, for temporary or permanent use, including the possibility of physical and/or economic displacement and resettlement, which can, in turn, impact the human rights of neighboring communities. Depending on the specific societal context such as population density, land occupation and use, gender dimensions or livelihood patterns, there may be negative impacts on livelihoods.”

– TOTAL’S 2016 HUMAN RIGHTS BRIEFING PAPER

The company’s Incahuasi project, the development of which began in 2012, faced challenges in its relationship with Guaraní communities when, during excavation activities in preparation for the construction of a gas plant, archeological findings including artifacts and burial remains were uncovered. In response to these developments and corresponding tensions with local indigenous leaders, the company engaged a conflict transformation specialist, a historian specializing in Bolivian indigenous groups, and the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights in Bolivia to carry out cross-functional human rights workshops and awareness-raising among TEPBO staff.

“Access to land can be a significant issue, both in developed and developing countries, and it is a particularly important topic in areas where land is used by communities for farming, tourism or where there are cultural heritage concerns around land. It can also be especially complex in developing countries where land grabbing could be prevalent and where the land titling process is inefficient or not transparent. Our operations are sometimes located in these challenging environments. Some of our societal assessments and human rights assessments have shown that land access is a significant human rights issue in our operations.”

Total’s 2016 Human Rights Briefing Paper

The response

Under the umbrella of “human rights and local communities,” Total has identified its salient human rights – the human rights at risk of the most severe impacts in the company’s operations and supply chains – to include access to land. The oil and gas company’s salient issues also include land-related issues such as the right to health and the right to an adequate standard of living since “[n]oise, dust, emissions and other impacts could have implications for the health of local communities, their livelihood and access to ecosystem services – i.e. services delivered by nature to people – like drinking water.”

In the context of its experience with the Incahuasi Project, TEPBO reexamined its community relationship approach in the country, particularly when it comes to communication and participatory strategies for social and environmental impact assessments. In 2015, TEPBO began environmental and social studies of exploration activities for its Azero Project, which covers a land block adjacent to the Incahuasi Project area. The Azero block contains a national park, presenting heightened risk for additional land-related human rights impacts and associated company-community conflict.

In its exploration and production (E&P) business segment, Total has instituted a Community Liaison Officer (CLO) program as part of its efforts to address these salient issues. CLOs are “typically members of the local community, whose language they speak and whose customs they understand,” and they are directly employed by Total’s business units to maintain a dialogue with local communities impacted by the operations of the company or its affiliates.

Implementing new strategies based on its experience with the Incahuasi Project, TEPBO has subsequently taken a distinct approach in its Azero Project. The company’s new model incorporates a key role for its CLOs and recognizes the need for heightened measures that go beyond expectations laid out in national regulations when it comes to community consultation and participation around land.

“Our approach in the Azero project in Bolivia has required that we go beyond compliance of local legal standards and put in efforts to engage in meaningful consultation with affected communities and reach international expectations. For that purpose, initiating early engagement, by conducting in-house baseline social studies with a participatory approach and with a highly trained and well-respected CLO team, has been challenging at times but a very fruitful experience that we are now aiming to replicate elsewhere. We’ve observed the communities that we’ve worked with knowing and claiming their rights based on this experience and now asking their leaders and other companies to meet these higher standards as well. Another important component has been engaging external stakeholders like International Alert, CDA, and Oxfam to consistently challenge us, bring constructive insights, and foster the effectiveness of our social performance.”

– CYNTHIA TRIGO, TOTAL

Key aspects of the initiative

TEPBO’s CLO approach to dialogue with the Guaraní groups potentially affected by activities associated with the Azero project includes the following components:

- Social baseline study at the start of exploration activities, conducted by a team of CLOs who were also social science professionals. The study took a participatory approach, involving a wide range of indigenous representatives, not just traditional leaders. The aim of the various in-person meetings that took place as part of the study was to provide early transparency around the project and multiple opportunities for input regarding potential impacts and mitigation measures.

- Subsequent social impact assessments, carried out by consultants but also taking a participatory approach with the affected communities who identified and validated the potential impacts of the project.

- Gap analysis by external experts around the concept of free, prior and informed consent (FPIC), drawing from the expectations set out in the International Finance Corporation’s Performance Standards.

- Building out of internal TEPBO “societal team” with experts in community engagement and relationship management in Bolivia, alongside ongoing engagement with key stakeholder groups such as local government authorities, local offices of international human rights organizations, and expert civil society organizations.

“Companies should start engaging potentially impacted communities as early as possible. Part of what we’ve learned from our experiences in Bolivia is that strong management systems around land and human rights issues need to be put in place at the exploration phase if risks and impacts are to be correctly understood and addressed. These issues can then be better integrated throughout decision-making processes and the company’s relationship with communities is then more likely to be positive throughout the course of the project. This engagement, early and often, is a smart investment, not simply an additional cost. For instance, our hiring of CLOs and investment in community relationship programs make good business sense in addition to being part of Total’s responsibility to respect human rights.”

Cynthia Trigo, Total