On October 5, 2021 GRI launched their revised Universal Standards to help companies report on their impacts on the economy, planet and people. Shift’s President Caroline Rees joined Matthias Thorns (IOE) and Jyrki Raina for a conversation on what the update means for companies.

Archives: Resources

Statement of Cooperation between EFRAG and Shift

The PTF-ESRS announced the signing of a Statement of Cooperation with Shift. Both organizations will put together their experience and expertise to encourage the swift development of European sustainability reporting standards in the social domain and at the same time the progress of converged standards at international level. Each organization will contribute to key technical projects of its counterpartin the social domain.

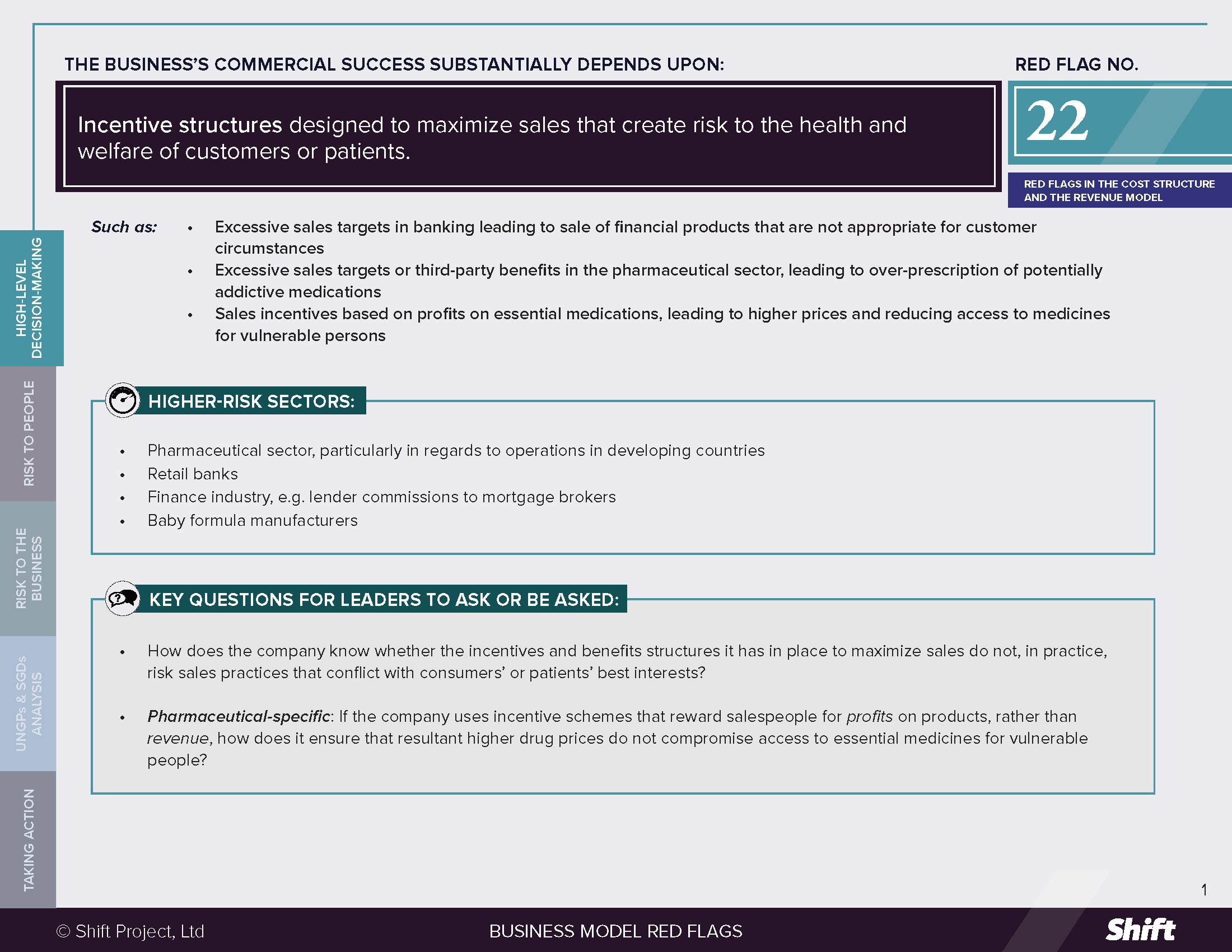

Red Flag 22. Sales-maximizing incentives that put consumers at risk

RED FLAG # 22

Incentive structures designed to maximize sales that create risk to the health and welfare of customers or patients.

For Example

- Excessive sales targets in banking leading to sale of financial products that are not appropriate for customer circumstances

- Excessive sales targets or third-party benefits in the pharmaceutical sector, leading to over-prescription of potentially addictive medications

- Sales incentives based on profits on essential medications, leading to higher prices and reducing access to medicines for vulnerable persons

Higher-Risk Sectors

- Pharmaceutical sector, particularly in regards to operations in developing countries

- Retail banks

- Finance industry, e.g. lender commissions to mortgage brokers

- Baby formula manufacturers

Questions for Leaders

- How does the company know whether the incentives and benefits structures it has in place to maximize sales do not, in practice, risk sales practices that conflict with consumers’ or patients’ best interests?

- Pharmaceutical-specific: If the company uses incentive schemes that reward salespeople for profits on products, rather than revenue, how does it ensure that resultant higher drug prices do not compromise access to essential medicines for vulnerable people?

How to use this resource. ( Click on the “+” sign to expand each section. You can use the side menu to return to the full list of red flags, download this Red Flag as a PDF or share this resource. )

Understanding Risks and Opportunities

Risks to People

Incentive and benefit structures, a key component of the sales promotion strategy of many companies, are designed to reward salespeople for revenue generated for the business. However, such structures can lead to negative outcomes for people where targets are excessively high, practices are subject to inadequate oversight, promotion activities towards third parties lead to over – or inaccurate prescription or recommendations, and, in some cases, where incentives are profit-based.

- Excessive sales targets and inadequate oversight can lead to predatory sales behavior. In the retail banking industry, this has included:

- Unauthorized transactions on client accounts;

- Sale of insurance products to clients who do not meet eligibility requirements (and therefore cannot take advantage of them);

- Targeting the elderly or people conversing in their second language;

- Sale of loans to people who cannot meet repayment obligations. (Privacy and Information rights; Economic security rights; Right to an adequate standard of living; Right to housing).

- Heightened risks arise where salespeople are required to use discretion in evaluating customer fitness for access to a product and/or have the ability to access/ modify private customer information without adequate oversight.

- Influencing third parties leading to excessive or inappropriate prescription or recommendation of products: Where incentive structures influence a professional’s exercise of discretion, people may be given advice or products that are not appropriate for their personal circumstances, affecting their health and/or finances:

- Provision of baby formula to mothers in poverty by hospitals/ doctors receiving samples from companies, with subsequent impact on child health as mothers abandoned breastfeeding but could not afford an adequate amount of formula (see OHCHR) (Right to life; Right to health);

- Sale of “sub-prime” loans by mortgage brokers receiving commissions from lenders, at interest rates above market and/or to borrowers who could not afford repayments (see CESR) (Right to an adequate standard of living, including Right to Housing); and

- Over-prescription of potentially addictive painkillers facilitating or leading to addiction (Right to life; right to health).

- In the context of essential medicines, sales incentives that reward based on profits on products (rather than revenue) can drive up the price of essential medicines, reducing access to medicines for vulnerable persons (Right to life; Right to health).

Risks to the Business

- Reputational, Financial and Business Opportunity Risks: Scrutiny from governments, investors and civil society is becoming increasingly sophisticated and granular, including to the level of the existence and effect of sales targets. One example is the well-known Access to Medicine Index for the pharmaceutical industry, which includes Market Influence within its measurement areas, including “sales-based performance incentives and bonuses for sales agents.” Consequently, companies are unable to claim ignorance of expectations and best practices; to do so risks loss of investment, reputational risks and loss of access to business partners applying such standards in their criteria for engagement.

- Regulatory Risks: The impacts flowing from excessive sales targets and inadequate oversight can affect the reputation of an entire industry and potentially lead to increased regulation. The Banking Royal Commission in Australia was established in 2017 to inquire into and report on misconduct in the banking, superannuation and financial services industry, including fraudulent lending to elderly customers and the widespread provision of inappropriate and predatory financial planning advice. It was reported in 2020 that “about 40 pieces of … legislation sit on [the government’s] parliamentary agenda.”

- Reputational, Financial, Business Continuity, Regulatory and Legal Risks: As the impacts associated with this red flag tend to accumulate over time and exacerbate exiting social vulnerabilities, when impacts reach public consciousness, they tend to do so explosively, in the form of scandals, exposés and the partial collapse of industries. Companies face resulting litigation, increased scrutiny and regulation and reputational damage. For example, in the context of aggressive sales tactics and over-prescription in the opioid crisis, drug companies faced lawsuits, saw their reputation damaged and stock lose value. Reportedly 70% of Americans support “making drug companies pay the cost of addiction treatment services and cover the cost of naloxone, used to revive people who’ve overdosed.”

What the UN guiding principles say

*For an explanation of how companies can be involved in human rights impacts, and their related responsibilities, see here.

The UNGPs note that companies should “strive for coherence between their responsibility to respect human rights and policies and procedures that govern their wider business activities and relationships. This should include, for example, policies and procedures that set financial or other performance incentives for personnel…”. (Principle 16, Commentary).

- Where salespeople undertake predatory or unethical behavior on behalf of the company, the company may cause any human rights impacts suffered by customers as a result.

- Where companies offer certain kinds of incentives in higher risk contexts, they risk contributing to impacts, e.g. if a pharmaceutical company operating in countries where access to medicine is a salient risk does not take steps to decouple incentive schemes from the cost of essential medicines.

- Companies that offer incentives to third parties in order to sway their advice to customers/patients may contribute to impacts suffered by those that receive inappropriate advice or products.

Possible contributions to the SDGs

Addressing risks to people associated with this red flag indicator can contribute to, inter alia:

SDG 1: No Poverty, in particular Target 1.4: By 2030, ensure that all men and women, in particular the poor and the vulnerable, have equal rights to economic resources, as well as access to basic services, ownership and control over land and other forms of property, inheritance, natural resources, appropriate new technology and financial services, including microfinance.

SDG 3: Good Health and Well-Being, in particular Target 3.5: Strengthen the prevention and treatment of substance abuse, including narcotic drug abuse and harmful use of alcohol. Target 3.8: Achieve universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health-care services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all.

SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth, in particular Target 8.10: Strengthen the capacity of domestic financial institutions to encourage and expand access to banking, insurance and financial services for all.

Taking Action

Due diligence Lines of Inquiry

Promotional practices influencing third parties

- Do we have a policy in our marketing practices with regard to potential human rights impacts, and do we include our marketing practices as part of our human rights due diligence?

- What evidence do we have as to whether our salespeople are acting in practice in line with our marketing policies and prescribed processes?

- What are the different contexts in which our products/services will be sold/recommended to individuals? How might poverty, a lack of information or other vulnerabilities affect potential impacts from our products? What strategies do we have in place to ensure that our products are not sold/recommended in circumstances where the products might lead to harm to our customers?

- Do we provide adequate training to our sales professionals to enable them to make decisions guided by our human rights responsibilities?

- How might our salespeople, or the professionals they influence, be incentivized to act otherwise than in accordance with our policies?

- Do we have sufficient oversight over our salespeoples’ activities? How do we internally/ externally audit our practices?

- What grievance mechanisms do we have, who can access them and how do we act on results?

Sales targets and predatory sales behavior

- Who are our most vulnerable potential customers? How can our products/ services potentially be connected to negative impacts on people?

- Do our salespeople exercise discretion in evaluating the appropriateness of a product for customer? How is this guided or constrained?

- How can we track any increases in sales to potentially vulnerable people?

- In practice, how do our salespeople experience the relative pressures to both deliver on sales targets and protect vulnerable people from potential impacts associated with our products/services? Do they find the two to be in tension and do they know how to address those tensions in practice?

- Do our salespeople have the ability to access/modify private customer information? What protections/ oversight is in place?

Profit-based incentives and access to medicine

- How do we incentivize our sales teams across geographies in which we operate? Do our incentive structures reward for profits on products (as opposed to revenue)?

- Could our incentives structures be playing a role in high/ rising drug prices?

- If so, do we whether higher prices could exacerbate existing vulnerabilities among potential consumers and limit access to essential medicines?

- Can we find a way to decouple sales agents’ incentives from sales targets?

Sales incentives and over-prescription in pharmaceuticals

- Do we offer sales bonuses based on sales volume in the context of drugs prone to over-prescription?

- Could we avoid deploying sales agents for such medicines, or decouple sales bonuses from volumes?

Mitigation Examples

*Mitigation examples are current or historical examples for reference, but do not offer insight into their relative maturity or effectiveness.

Removing sales-based incentives:

- According to the 2018 Access to Medicines Index, GSK’s sales agents’ rewards are not solely based on sales targets. Instead, it “rewards other qualities such as technical knowledge and quality of service” (p.134). Novartis also “rewards other aspects such as performance, innovation, collaboration, courage and integrity” (p.138).

- In order to “help our customers out rather than catch them out with unexpected charges, short-term offers and products they do not need,” Natwest and Royal Bank of Scotland “remove[d] sales-based incentives from customer-facing employees in Personal and Business Banking, ensuring that staff are completely focused on meeting the needs of customers rather than selling products.” To mitigate the impact on salespeople, the banks “gave every eligible employee an increase to their guaranteed pay.”

- To address over prescription, pharmaceutical companies Cipla and Shionogi have “minimised the incentive to oversell by decoupling their sales agents’ financial rewards from the volume of antibacterial and antifungal medicines they sell.”

Alternative Models

Avoiding sales agents altogether: Johnson & Johnson, Otsuka and Teva do not deploy sales agents for at least some antibacterial and antifungal medicines.

Other tools and Resources

- Sales Incentives and Over Prescription: The Access to Medicine Foundation’s Antimicrobial resistance benchmark “evaluates how 30 pharmaceutical companies are responding to the global threat of antimicrobial resistance” including their sales promotion practices.

- Profit-based Incentives and Access to Medicine: Information on pharmaceutical companies’ performance on “Market Influence,” including sales incentives, can be found in the Access to Medicine Index.

- Financial Services Misconduct: e.g., Submission of Dr. Kym Sheehan and Prof. David Kinley of Sydney Law School to the Australian Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking and Financial Services Sector.

- Misleading marketing practices of infant formula in developing countries: OHCHR (2015) Breastfeeding a matter of human rights, say UN experts, urging action on formula milk.

Citation of research papers and other resources does not constitute an endorsement by Shift of their conclusions.

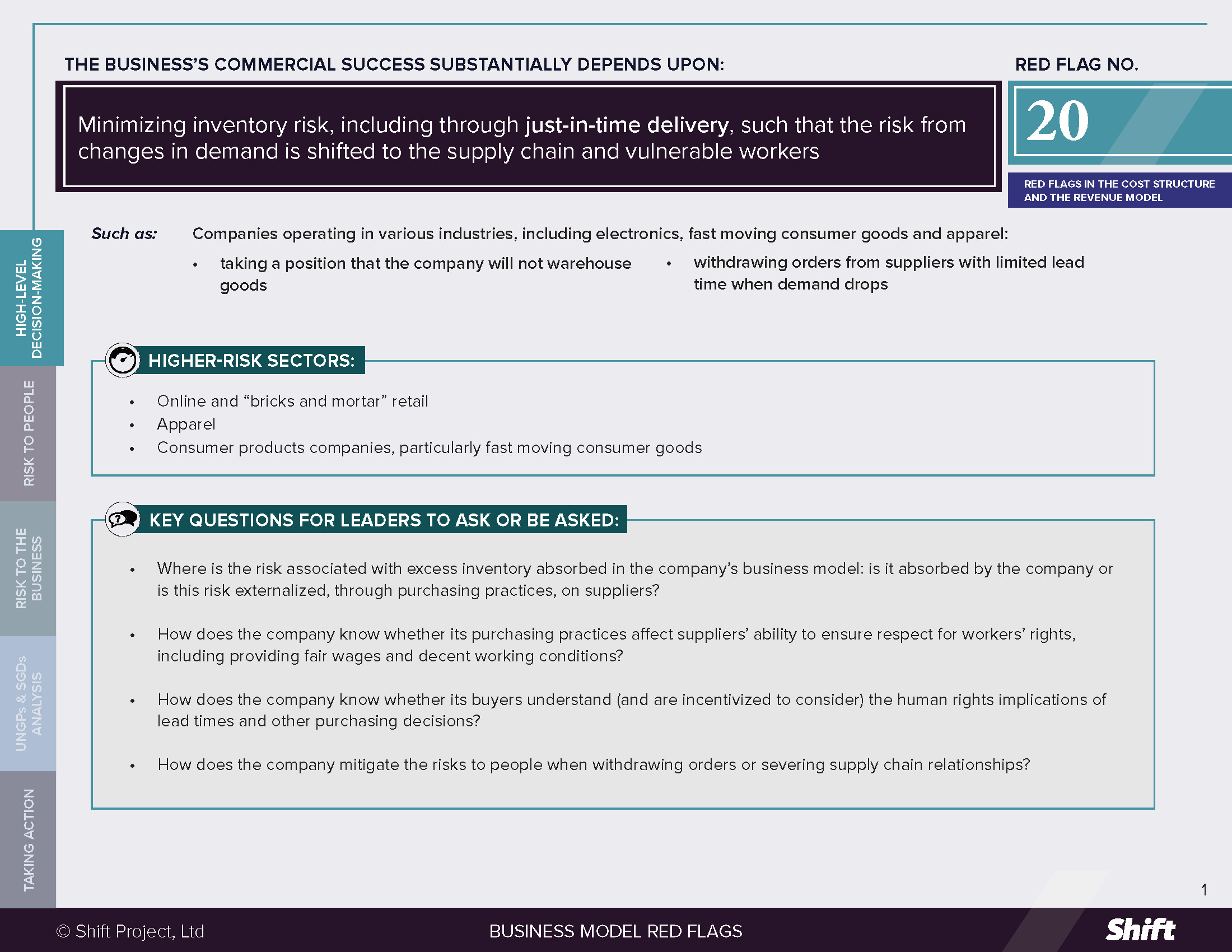

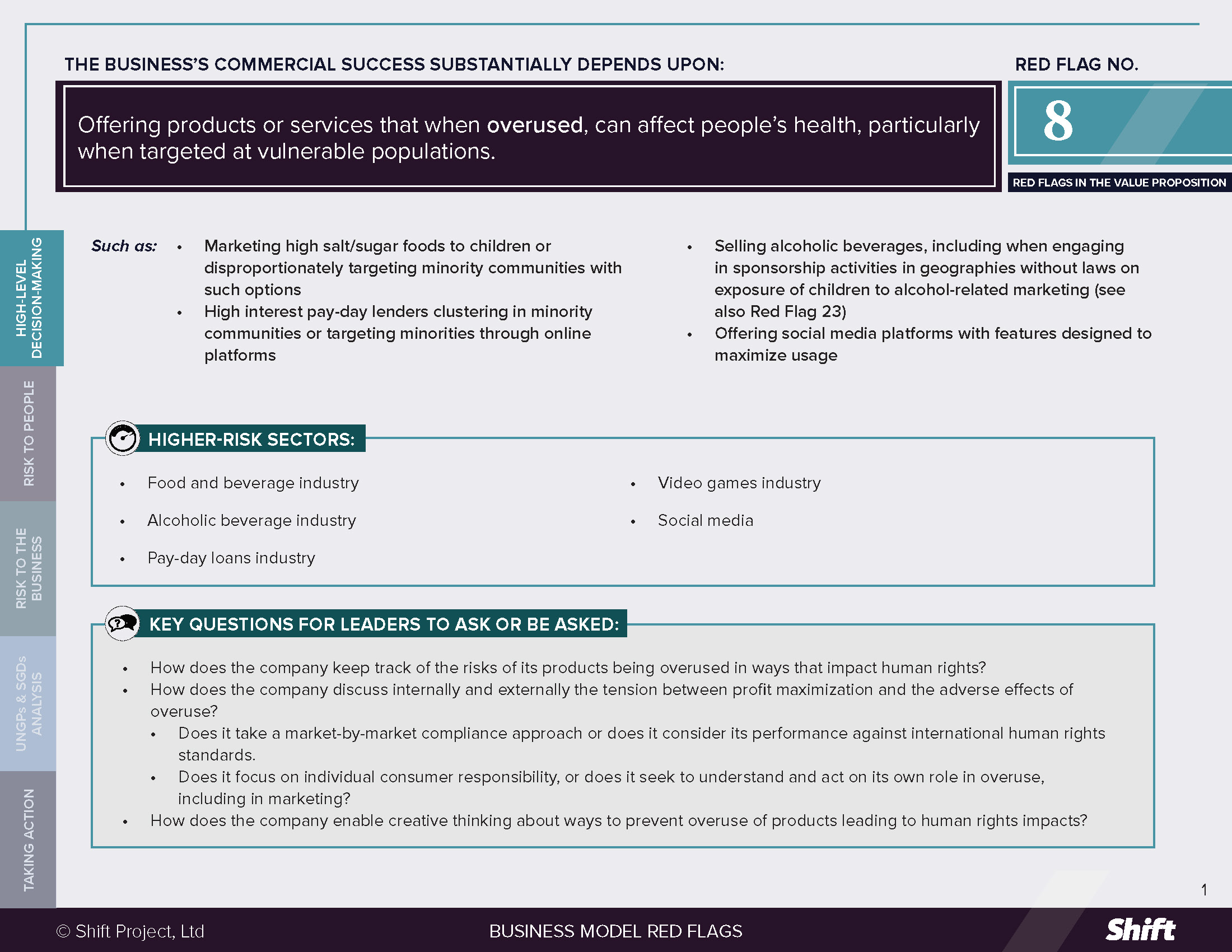

Red Flag 20. Shifting inventory risk to suppliers with knock-on effects to workers

RED FLAG # 20

Minimizing inventory risk, including through just-in-time delivery, such that the risk from changes in demand is shifted to the supply chain and vulnerable workers.

For Example

Companies operating in various industries, including electronics, fast moving consumer goods and apparel:

- taking a position that the company will not warehouse goods

- withdrawing orders from suppliers with limited lead time when demand drops

Higher-Risk Sectors

- Online and “bricks and mortar” retail

- Apparel

- Consumer products companies, particularly fast moving consumer goods

Questions for Leaders

- Where is the risk associated with excess inventory absorbed in the company’s business model: is it absorbed by the company or is this risk externalized, through purchasing practices, on suppliers?

- How does the company know whether its purchasing practices affect suppliers’ ability to ensure respect for workers’ rights, including providing fair wages and decent working conditions?

- How does the company know whether its buyers understand (and are incentivized to consider) the human rights implications of lead times and other purchasing decisions?

- How does the company mitigate the risks to people when withdrawing orders or severing supply chain relationships?

How to use this resource. ( Click on the “+” sign to expand each section. You can use the side menu to return to the full list of red flags, download this Red Flag as a PDF or share this resource. )

Understanding Risks and Opportunities

Risks to People

- Some business models support commercial viability by externalizing the risks associated with changing levels of consumer demand on suppliers, rather than absorbing it in the business model.

- Companies may do this by way of:

- Making last minute demands, changes or cancellation of orders;

- Using contracts by which the supplier assumes the cost and risk of the product until delivered;

- Avoiding warehousing goods by utilizing a “just in time” inventory/sourcing model.

- As a result:

- When demand spikes, and the purchasing company places large volume orders with short lead times, suppliers may see no alternative but to demand excessive overtime. (Right to just and favorable conditions of work; Right to a family life; Right to Health).

- A joint ETI/ILO survey on purchasing practices in 2017, to which responses were received from over 1,400 suppliers in 87 countries, found that only 17% of suppliers surveyed considered their orders to have enough lead time.

- When demand drops, the purchasing company may cancel orders on short notice and/or refuse to take responsibility for goods that have already been produced. IndustriALL has noted that such cancellations leave factories holding the goods, unable to sell them to the customer that ordered them, and in many cases unable to pay the wages of the workers who made them.

- When demand spikes, and the purchasing company places large volume orders with short lead times, suppliers may see no alternative but to demand excessive overtime. (Right to just and favorable conditions of work; Right to a family life; Right to Health).

- Purchasing practices such as this may, without appropriate mitigation measures, place heavy pressure on suppliers working on narrow margins. Risk and its associated costs are pushed up the supply chain and absorbed by the most vulnerable people – such as factory workers, including migrant workers, women workers, producers and small-holder farmers – affecting their livelihoods and those of their families. Suppliers under excessive pressure may not pay wages or overtime, or not provide safe working conditions; they may pregnancy test workers pursuant to a view that pregnant workers are not financially viable. Risks are exacerbated when the purchasing company(ies) provide little or no commitment to long-term sourcing, disincentivizing investment in improving working conditions (Right to just and favorable conditions of work; Right to Health).

Risks to the Business

- Operational Risks:

- Purchasing practices that situate inventory risk with suppliers can leave suppliers with cash flow challenges and unpredictability that disincentivizes them from investing in compliance with codes of conduct. Such practices can also cause suppliers to outsource (including illegally) to subcontractors, increasing the complexity of the supply chain and reducing visibility and control on the part of the buying company.

- Where the company does not keep an inventory of its products and relies on a small number of suppliers, it can be vulnerable to inventory shortages: in 2019, German-based Adidas’s sales growth declined due to “supply chain shortages” when “the company’s suppliers—nearly all of whom are based outside Germany—did not keep up with customer demand.”

- The Covid-19 situation in 2020 further demonstrated the risks to the company of relying on, inter alia, just in time models and the detrimental impact of this practice on supply chain resilience.

- Reputational and Financial Risks:

- Companies with purchasing practices that lag behind leading practices may receive poor results in the Better Buying review, a growing online platform that allows suppliers to anonymously rank the buying practices of brands and retailers.

- During the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic, companies leaving overseas suppliers with excess inventory received negative publicity, including through Workers’ Rights Consortium’s “Brand Tracker” which listed apparel labels and retailers that were and were not paying their suppliers for orders in production or completed. From an investment perspective, research on the link between public sentiment on corporate responses to the pandemic and financial flows found that companies with labor and supply chain practices that were seen as taking action to secure their supply chain experienced higher institutional money flows and less negative returns.

What the UN guiding principles say

*For an explanation of how companies can be involved in human rights impacts, and their related responsibilities, see here.

The UNGPs note that companies should “strive for coherence between their responsibility to respect human rights and policies and procedures that govern their wider business activities and relationships [including] …. procurement practices.” (Principle 16, Commentary).

If a company engages in purchasing practices that place undue time and/or financial pressure on suppliers, incentivizing or facilitating them to cause human rights impacts on workers, they contribute to impacts.

Possible Contributions to the SDGs

Addressing risks to people associated with this red flag indicator can contribute to, inter alia:

SDG 10: Reducing inequalities within and between countries.

This goal becomes relevant as profit margins and returns are concentrated at the buyer/investor level, with less and less value making it into the pockets of the poorest in the supply chain.

SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth, in particular Target 8.8 on protecting “labor rights and promot[ing] safe and secure working environments for all workers, including migrant workers, in particular women migrants, and those in precarious employment.

SDG 1: End Poverty in All its Forms Everywhere, in particular Targets 1.1 and 1.2 on eradicating extreme poverty and reducing by half the number of people living in poverty (according to national definitions).

Taking Action

Due Diligence Lines of Inquiry

- Do we have sufficient budget allocated to warehousing products? If not, how are we ensuring that factories can produce in advance and keep overtime within acceptable limits?

- Do buyers have sufficient knowledge, incentives and support to assess how and when their decisions will place human rights at risk, and to know from whom to seek assistance when they do?

- How do we know whether our buyers follow our processes, rules or guidelines in practice when engaging or contracting with suppliers?

- Do we engage with our suppliers in ways that help us understand how far they can go to meet our demands while still respecting the rights of their workers? Do we work with suppliers in countries of production to increase worker protections?

- Do we take a short term, transactional approach to supply chains or do we develop supply chain partnerships? For example, do we see high turnover among suppliers?

Mitigation Examples

*Mitigation examples are current or historical examples for reference, but do not offer insight into their relative maturity or effectiveness.

- “Kellogg undertakes a ‘joint business planning process’ with its key suppliers that includes the evaluation of its responsible sourcing practices. Issues such as purchasing practices, ordering, lead-time expectations, production schedule changes, and complicated specifications for ingredients and sizes are discussed with suppliers and that responsible sourcing is also embedded in global sourcing events and category development. In addition, Kellogg discloses that procurement leadership and category managers are responsible for the execution of the Global Sustainability Commitments, including social accountability, which is reflected in their annual performance plans and annual incentives.” (Know the Chain).

- ACT (Action, Collaboration, Transformation) is an “agreement between global brands and retailers and trade unions to transform garment, textile and footwear industry and achieve living wages for workers through collective bargaining at industry level linked to purchasing practices.” In September 2019, ACT adopted a joint due diligence framework including Global Purchasing Practices Commitments, a Responsible Exit Policy and Check List and a Purchasing Practices Self-Assessment tool (covering64 different aspects of purchasing practices in 16 areas), including a commitment to “fair terms of payment” and “better planning and forecasting.” The ACT Accountability and Monitoring framework provides ACT member brands with an agreed set of indicators and monitoring instruments to implement their purchasing practices commitments.

- At a time of decreased sales during the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic, UK supermarket Morrisons committed to advancing payments to its smaller foodmakers, farmers and businesses that stock its shelves; H&M announced that it would take delivery of already produced garments, as well as goods in production, and that the goods would be paid for under previously agreed payment terms and prices; L’Oréal prioritized immediate payments to and shortening payment terms with suppliers who were at risk of going out of business; and Unilever offered early payment to its most vulnerable small and medium-sized suppliers to help them with financial liquidity. (See Triponel and Sherman (2020)). Primark created the Primark Wage Fund, Asia to help pay the wages of garment workers affected by Primark’s decision to cancel clothing orders.

Alternative Models

Spanish fashion company Alohas’ “business model revolve[s] around an on-demand production process.” The company previews upcoming designs to customers early in the season and makes them available at a discount rate. Once it calculates how many units of each new style should be produced it commences manufacturing. Alohas notes that “on-demand reverts the sales cycle by applying a discount for early purchases and offering the product at full price only once stock has been made available. Meaning we don’t adhere to the traditional sales calendar anymore.”

Other Tools and Resources

- ACT (Action, Collaboration, Transformation), including the ACT Global Purchasing Practices Commitments.

- ILO (2017) Purchasing practices and working conditions in global supply chains: Global Survey results: provides the results of an ILO/ETI global survey on purchasing practices and working conditions, to which over 1,400 suppliers from 87 countries responded, with the sample covering nearly 1.5 million workers.

- ETI (2017) Guide to Buying Responsibly: The guide includes best practice examples and outlines the five key business practices that influence wages and working conditions.

- Better Buying has created a tool for suppliers to anonymously rate their buyers against 7 purchasing practices, developed through consultation with suppliers. Buttle (2018) Can there be fair rules for the ‘purchasing practices’ game?: a ETI blog post from ETI’s Apparel and Textiles Lead summarizes standards for company purchasing practices and offers recommendations for improvements in practice.

- Workers’ Rights Consortium’s “Brand Tracker” lists apparel labels and retailers that were and were not paying their suppliers for orders in production or completed during the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic.

- A. Triponel and C Bader (2020) Coronavirus is shining the spotlight on unhealthy supply chains: cleaning them up will help both business resilience and worker wellbeing.

- A. Triponel and J. F. Sherman (2020) Moral bankruptcy during times of crisis: H&M just thought twice before triggering force majeure clauses with suppliers, and here’s why you should too.

Citation of research papers and other resources does not constitute an endorsement by Shift of their conclusions.

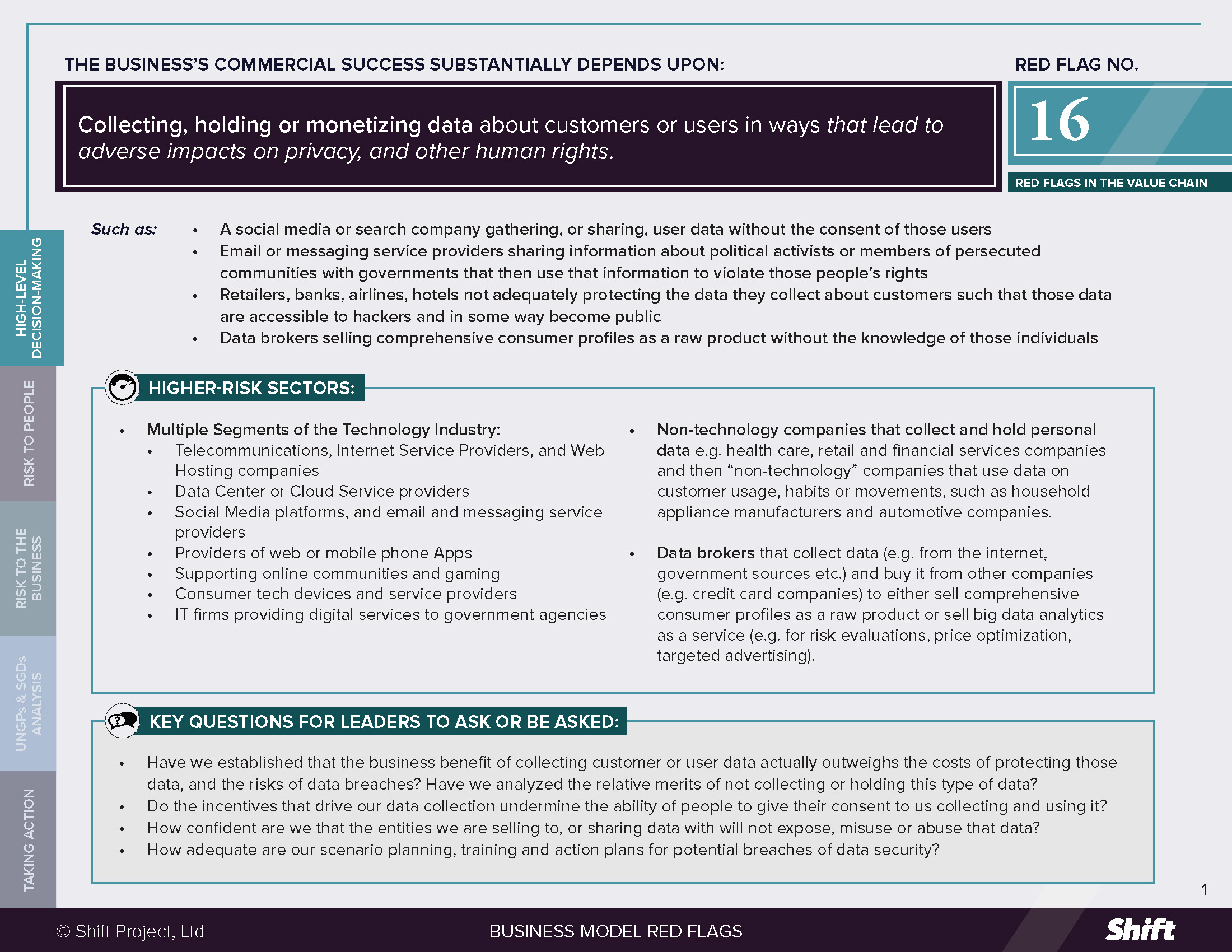

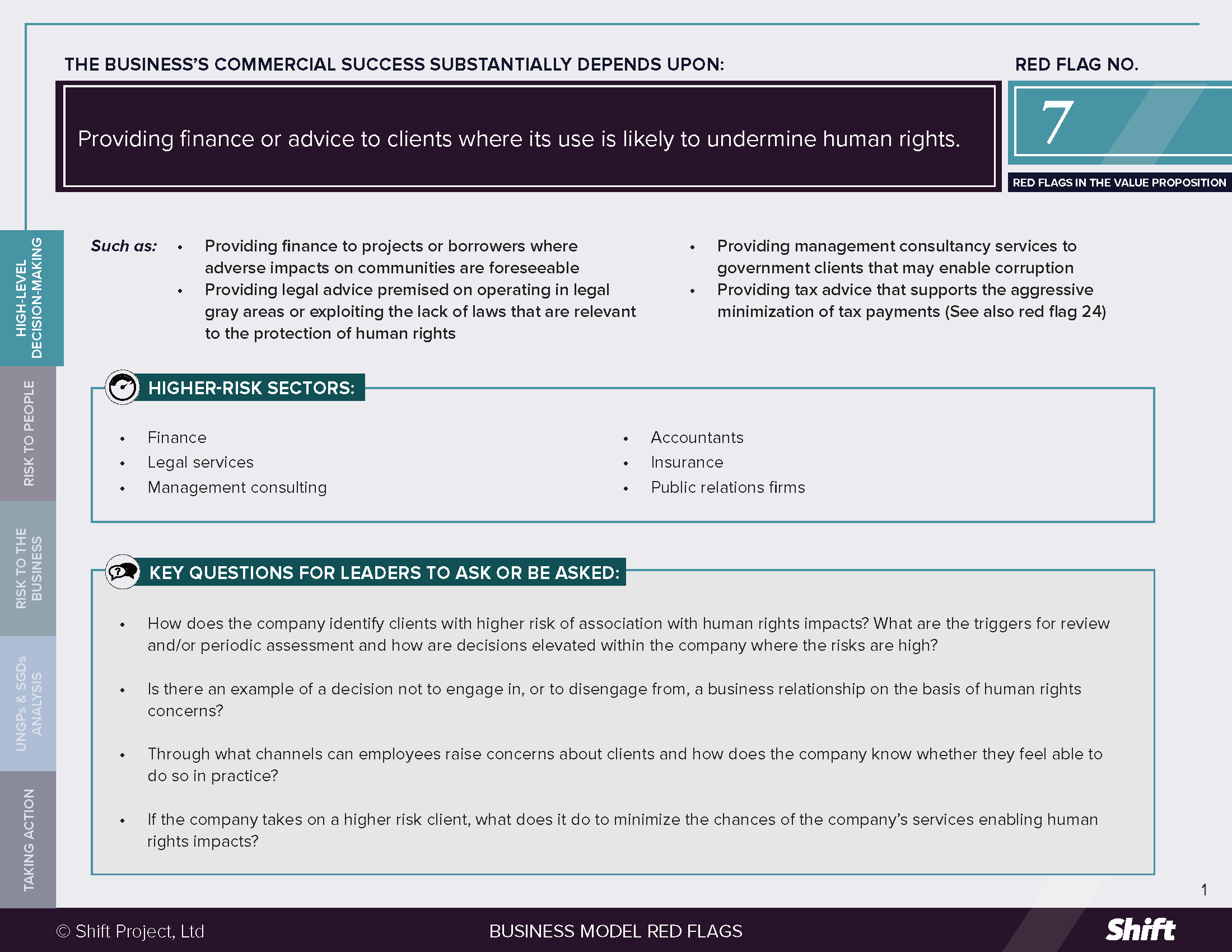

Red Flag 16. Using data such that privacy and other rights are undermined

RED FLAG # 16

Collecting, holding or monetizing data about customers or users in ways that lead to adverse impacts on privacy, and other human rights.

For Example

- A social media or search company gathering, or sharing, user data without the consent of those users

- Email or messaging service providers sharing information about political activists or members of persecuted communities with governments that then use that information to violate those people’s rights

- Retailers, banks, airlines, hotels not adequately protecting the data they collect about customers such that those dataare accessible to hackers and in some way become public

- Data brokers selling comprehensive consumer profiles as a raw product without the knowledge of those individuals

Higher-Risk Sectors

- Multiple Segments of the Technology Industry:

- Telecommunications, Internet Service Providers, and Web Hosting companies

- Data Center or Cloud Service providers

- Social Media platforms, and email and messaging service providers

- Providers of web or mobile phone Apps

- Supporting online communities and gaming

- Consumer tech devices and service providers

- IT firms providing digital services to government agencies

- Non-technology companies that collect and hold personal data e.g. health care, retail and financial services companies and then “non-technology” companies that use data on customer usage, habits or movements, such as household appliance manufacturers and automotive companies.

- Data brokers that collect data (e.g. from the internet, government sources etc.) and buy it from other companies (e.g. credit card companies) to either sell comprehensive consumer profiles as a raw product or sell big data analytics as a service (e.g. for risk evaluations, price optimization, targeted advertising).

Questions for Leaders

- Have we established that the business benefit of collecting customer or user data actually outweighs the costs of protecting those data, and the risks of data breaches? Have we analyzed the relative merits of not collecting or holding this type of data?

- Do the incentives that drive our data collection undermine the ability of people to give their consent to us collecting and using it?

- How confident are we that the entities we are selling to, or sharing data with will not expose, misuse or abuse that data?

- How adequate are our scenario planning, training and action plans for potential breaches of data security?

How to use this resource. ( Click on the “+” sign to expand each section. You can use the side menu to return to the full list of red flags, download this Red Flag as a PDF or share this resource. )

Understanding Risks and Opportunities

Risks to People

There are a range of reasons why companies in diverse sectors are collecting and holding data. For example, private hospitals and pharmaceutical companies may do so to improve diagnoses, improve treatment plans and develop medicines; banks may use personal and transaction data to identify fraud; and autonomous vehicle companies may seek to monetize data about customer driving habits to enable individuals to improve insurance premiums. Even so, in order to fully realize these benefits for businesses and people, the following risks must be managed.

- Right to Privacy: Where a company collects, holds or provides third parties with access to data about customers or users, there are inherent and widespread privacy risks. Examples include:

- Where information about an individual is collected, sold or shared without their consent. This includes when data are used for purposes beyond those originally consented to by a “data subject.”

- Where data breaches result in individuals’ personal financial or health data being publicly accessible.

- Breaches of sensitive personal information, such as racial or ethnic origin, political opinions, religious or other beliefs, trade union membership, sex, gender identity or sexual orientation, genetic data, biometric data, or data concerning health.

- Freedom from Arbitrary Attacks on Reputation and Right to an Adequate Standard of Living: Where the personal data becomes accessible to the public, this data can be used to threaten individuals or tarnish their reputations, which can in turn impact victims’ mental health, job prospects and livelihoods.

- Government Requests Leading to Abuses of Freedom of Expression and other Human Rights: For example, where governments demand the company hands over:

- The communications history of political activists or human rights defenders and use it to identify, intimidate, threaten, detain and even torture them.

- Data about social media and other online activities of LGBTQI people that is used to violate their right to non-discrimination and rights to liberty and security.

- Risks to the Right to Non-Discrimination: Where data are used, shared or sold to third parties who use them in algorithmic decision-making that impacts their access to credit, welfare services, insurance or other services. (See Red Flag 5).

Risks to the business

- Regulatory Risks and Fines: Failure to protect user or customer privacy can lead to investigations, scrutiny and sanction, and many jurisdictions around the world are debating and enacting stricter laws to govern privacy, affecting multinational companies domiciled all over the world. The most notable of these are the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation which governs how personal data must be collected, processes and erased, and sets two-levels of fines.

- In 2020, British Airways was fined €22 million when their website diverted users’ traffic to a hacker website, impacting the data of over 400,000 customers.

- In 2019 Marriot International was fined €110 million related to a cyber-attack through which personal data from over 339 million guest records were exposed.

- In 2019, Google was fined €50 million due to a lack of meaningful consent about how data was being collected and used for the purposes of targeted advertising.

- In the United States, individual states have also put in place privacy regulations that apply to all industries. One such example is California’s Consumer Privacy Act.

- Legal Risk and Financial Settlements or Penalties: An increasing number of companies have been subject to lawsuits over inadequate action to address risks to people throughout the data lifecycle. Examples include:

- Facebook paying $550 million to settle a class action lawsuit from Illinois Facebook users accusing the company of violating an Illinois biometric privacy law.

- An £18 billion class action claim against Easy Jet in which the data of 9 million customers was accessed by third parties in a cyber-attack.

- Equifax, the US consumer credit score company, paying $425 million following a data breach affecting 147 million people in 2017, some of whom suffered identify theft, fraud and related legal or other costs.

- Operational Costs Following Breaches: Companies that experience a data breach faced immediate financial costs. The Home Depot breach of 56 million customer credit cards was estimated to cost $62 million to enable, among other steps: the post-breach investigation, call center staffing and monitoring of breached accounts for unusual activity. According to IBM’s 2020 Cost of Data Breach report, the global average total cost of a data breach is $3.86 million.

- Reputational Risk. Loss of Trust: A 2017 Forbes article notes that according to a PwC survey, “only 25% of consumers believe companies handle their personal information responsibly and 87% will take their business to a competitor if they don’t trust a company to handle their data responsibly.” An International Data Corporation study found that “80% of consumers in developed nations will defect from a business because their personally identifiable information is impacted in a security breach.”

- Stock Price Risk: There have been a number of reports about the impact of high-profile data breaches on company stock prices. The Facebook and Cambridge Analytica scandal of 2018 reportedly led to a $119 billion dollar loss in market value. A UK study notes that, “Companies that self reported their security posture as superior and quickly responded to the breach event recovered their stock value after an average of 7 days. In contrast, companies that had a poor security posture at the time of the data breach and did not respond quickly to the incident experienced a stock price decline that on average lasted more than 90 days.”

What the UN guiding principles say

*For an explanation of how companies can be involved in human rights impacts, and their related responsibilities, see here.

- A company can cause an adverse impact on the right to privacy of any stakeholder group that it collects data on, and at any stage of the data lifecycle.

- When Collecting Data: Although there are arguments that businesses obtain a “conscious compromise” from users about the exchange of information for goods and services, they may cause an impact on the right to privacy if the customer is not “truly aware of what data they are sharing, how and with whom, and to what use they will be put.” (The Right to Privacy in the Digital Age. OHCHR, A/ HRC/27/37).

- When Holding Data: A company may not have in place adequate security protections such that a human or system error results in personal data being accessible by third parties.

- A company’s use or mismanagement of data may contribute to a range of human rights harms depending on the context.

- Where a company suffers a data breach and personal data is accessed by a third party who then uses it to threaten the individuals whose data was leaked.

- Where a company makes a decision – even if consistent with local law – to provide personal data to a third party where it should have known that the data were likely to be used to abuse the rights of the data subjects concerned.

- Where companies (for example, banks and IT services firms, or automotive and insurance companies) work together to collect, analyze and interpret data in ways that lead to discriminatory pricing.

- Where a company sells or in some way shares personal data with business customers who in turn use those data in harmful ways.

-

A company can be linked to a human rights harm where it has sold or provided data to a business entity or government, and that entity uses those data in ways that are unforeseeable but nevertheless lead to adverse impacts on people.

Possible Contributions to the SDGs

Data about individuals can be used to advance a number of SDGs such as those listed below. Addressing impacts to people associated with this red flag can contribute to ensuring that this is done in ways that do not simultaneously increase discrimination, or erode the privacy, reputation and well-being of vulnerable communities.

SDG 10: Reduce Inequality within and Among Countries.

SDG 3: Healthy Lives and Well-Being for all. Including by tackling disruptions to progress such as from the COVID-19 global pandemic.

SDG 5: Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls, in particular: Target 5.b Enhance the use of enabling technology, in particular information and communications technology, to promote the empowerment of women.

SDG 9: Industries, Innovation and Infrastructure, in particular: Target 9.5 Upgrading industrial sectors; Target 9.b Domestic technological development; and Target 9.c: Access to technology and the internet.

SDG 17: Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the global partnership for sustainable development, in particular: Target 17.18 Increasing the availability of high-quality, timely and reliable data disaggregated to achieve development goals.

The UN Secretary-General’s Roadmap for Digital Cooperation is an important resource to guide “all stakeholders to play a role in advancing a safer, more equitable digital world” even as technological solutions are used to achieve the SDGs.

Taking Action

Due Diligence lines of Inquiry

- Do we have policies, processes and practices that follow the principle of data minimization such that we only collect or purchase data to the degree that is absolutely necessary to accomplish specific tasks we have in mind?

- Have we conducted an assessment, and where necessary put in place mitigation plans, for privacy and other risks to people that may arise across the data life cycle including generation, collection, processing, storage, management, analysis and interpretation?

- Have we done this for all stakeholder groups that may be at risk including employees, contract workers, prospective employees, customers and users?

- Are we engaging expert groups and potentially affected groups to ensure we understand the risks they perceive or experience?

- Do we assess whether and how our terms of service or policies for gathering and sharing customer data might increase human rights risks?

- Do we ensure that customers or users consent to how we gather and use their data, and that their consent is free and informed, including that they:

- Know that we gather and are in control of data about them.

- Are informed about how the data will be obtained and held, and for how long.

- Understand the operations that will be carried out on their data.

- Know how they can withdraw their consent for the use of their data.

- Where we buy data from another company, are we confident that it was legally acquired? Do we have ways to verify its accuracy?

- Where we sell or share data with third parties:

- Do we assess if they have the appropriate security and safeguards?

- Do we have in place a data sharing agreement that follows best practice?

- Do we retain a clear and up-to-date understanding of “data journeys” such that we can, where needed, take meaningful steps to delete the data in the event that we find it is used for human rights abuses?

- If we transmit data from customer devices, or allow messaging between users, do we have in place end-to-end encryption to prevent third parties from decrypting conversations? Have we developed an approach that takes into account the human rights benefits that can come from allowing third parties to scan for content (such as the ability to support legitimate criminal investigations)?

- If we face a risk of government demands for data where this may be used to abuse human rights, have we:

- Assessed ourselves against the Implementation Guidelines of the Global Network Initiative?

- Engaged with credible NGOs and human rights experts to understand these risks, and to prepare us to take action should government requests occur?

- Are our executives prepared for a breach? Have we done scenario planning and trained all relevant teams about what to do in the event of data breaches? In particular, do we have a clear action plan to ensure we inform our customers or users of breaches as fast as possible?

-

Do we have a comprehensive plan in place to respond to breaches, and specify how we’ll handle informing stakeholders? Are we clear on how we will provide for remedy if our actions contribute to the violation of user, customer, or employee privacy or other rights?

Mitigation Examples

*Mitigation examples are current or historical examples for reference, but do not offer insight into their relative maturity or effectiveness.

- Privacy Policy Hubs: Several businesses are building “hubs” for their privacy policies. Hubs are a dedicated area where data subjects (visitors to a website, customers, users) can go to view: how their data is being used; where it’s being used; how their data is being collected and what type; terms of the policy; and where subjects can revoke consent.

- Disney’s privacy hub also states how they protect children – their largest and most at-risk audience.

- Twitter’s privacy site includes information about how users’ tweets, location, and personal information are used.

- Cisco’s Trust and Transparency Center Online. In 2015, Cisco launched the Trust and Transparency Center online, which is dedicated to providing information, resources and answers to cybersecurity questions and to help manage security and privacy risk. The Centre includes Cisco’s Trust Principles, which describe their commitment to protect customer, product and company information, and it provides information about security policies and data protection programs.

- Participation in the Global Network Initiative: GNI is a multi- stakeholder initiative comprising companies, civil society organizations, investors and academics. GNI provides a framework to help ICT companies respect privacy rights, integrate privacy policies and procedures into corporate culture and decision making and communicate privacy practices with users. Members commit to an independent assessment process about how GNI principles are integrated within their organization.

- T-Mobile Do Not Sell Links: The California Consumer Privacy Act (2018) requires companies to post a clear and conspicuous link on their website that says, “Do Not Sell My Personal Information” through which consumers can opt out of the sale of their data to third parties. Some companies, like T-Mobile, apply this for all customers in the United States.

- Using Leverage to Regulate Data Brokers: In the United States, some business leaders (most notably Apple CEO Tim Cook) have called for a registry of data brokers to make their role in the collection, storing and selling of personal data more transparent and accountable.

-

The Microsoft Digital Crimes Unit: Microsoft’s digital crimes unit exists to “fight against cybercrime to protect customers and promote trust in Microsoft.” It operates globally through the application of technology, forensics, civil actions, criminal referrals, and public/private partnerships and is staffed by “an international team of attorneys, investigators, data scientists, engineers, analysts and business professionals located in 20 countries.”

Alternative Models

- Consumer Products and Services: A number of companies have launched privacy-oriented alternatives such as:

- Messaging App Signal: One of the only apps that has its privacy-preserving technology always enabled and ensures that there is never a risk of sharing moments or sending messages to a non-intended recipient. For more on messaging apps see this article.

- Search Engine Swisscows: Swisscows does not collect any of their visitors’ personal information such as an IP address, browser information, or device information. They do not record or analyze search terms. The only data that Swisscows records is the total number of search requests it receives each day.

- Enterprise Solutions: A 2020 World Economic Briefing, A New Paradigm for the Business of Data, profiles a small number of Enterprise and consumer solutions that place privacy, user consent and data security at the core. These include:

- Hewlett Packard Enterprise (HPE) and Continental: HPE and Continental have created the Data Exchange Platform as a marketplace for mobility data. “It provides a secure, transparent, decentralized architecture for trusted vehicle sensor data sharing and payment, based on blockchain technology and smart contracts. It offers data sovereignty and includes a consent- management system for drivers.”

- Inrupt: “Instead of a company storing siloed snippets of personal data on their servers, users store it in interoperable online data stores giving them unprecedented choices over how their data is shared and used. They can, for example, share their fitness data with their health insurance company, or allow sharing between their thermostat and air conditioner. They can set time limits on sharing and change their choices at any time.”

Other tools and resources

- Ranking Digital Rights Investor Outlook (2021) Geopolitical risks are rising—and regulation is coming.

- Institute for Human Rights and Business, Data Brokers and Human Rights.

- Global Network Initiative resources:

- Harvard Data Science Review, Jeanette Wing, The Data Life Cycle.

- Human Rights and Big Data Project, Developing an Online consent manifesto based on human rights.

- Information is Beautiful, Map of Data Breaches/Hacks: An interactive tool showing the world’s largest data breaches and hacks since 2009 up until the present. The map includes examples from 15 industry sectors and multiple well-known corporations including.

- Data Guise, Data Minimization in the GDPR: A Primer.

- UN Secretary-General’s Roadmap for Digital Cooperation.

Citation of research papers and other resources does not constitute an endorsement by Shift of their conclusions.

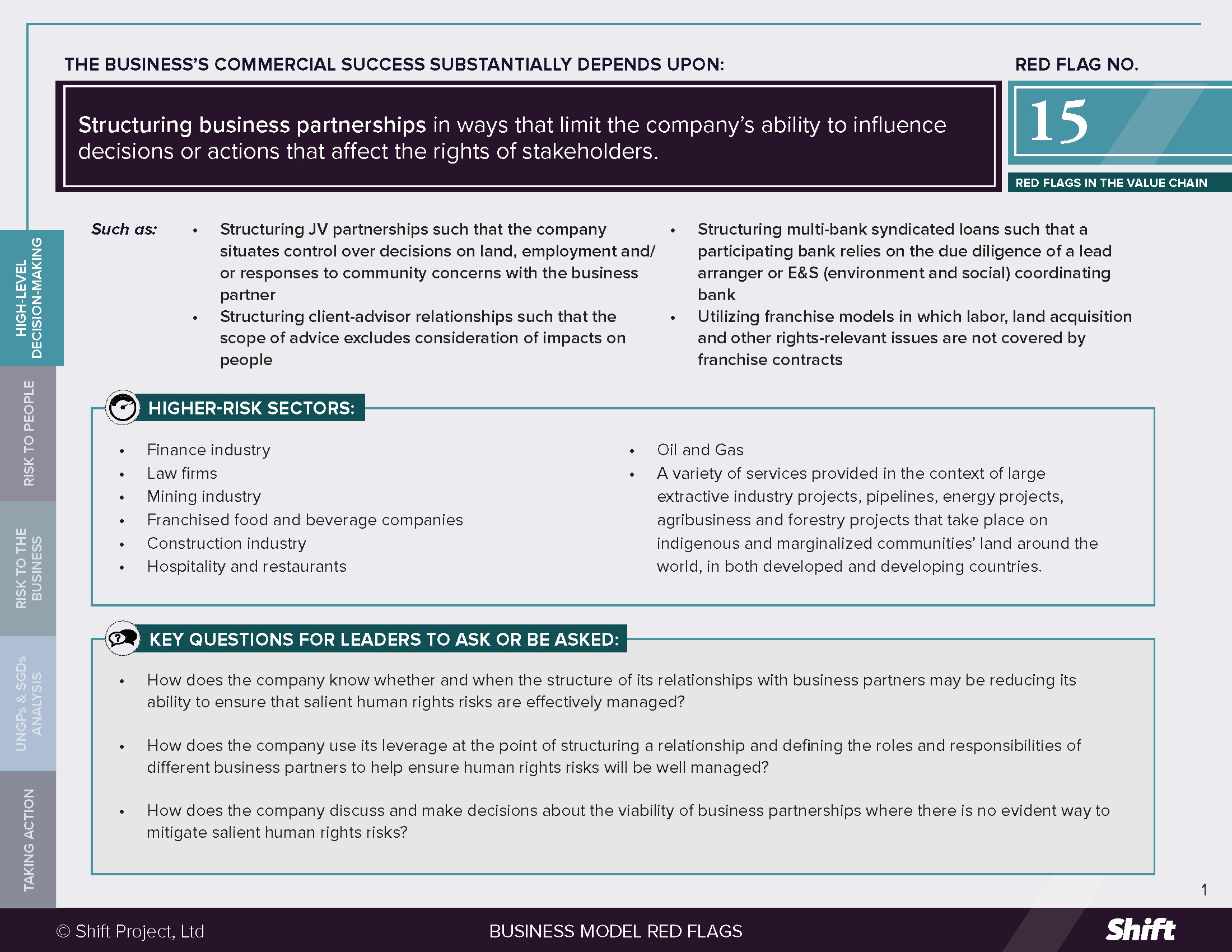

Red Flag 15. Business relationships with limited influence to address risk to people

RED FLAG # 15

Structuring business partnerships in ways that limit the company’s ability to influence decisions or actions that affect the rights of stakeholders.

For Example

- Structuring JV partnerships such that the company situates control over decisions on land, employment and/or responses to community concerns with the business partner

- Structuring client-advisor relationships such that then scope of advice excludes consideration of impacts on people

- Structuring multi-bank syndicated loans such that a participating bank relies on the due diligence of a lead arranger or E&S (environment and social) coordinating bank

- Utilizing franchise models in which labor, land acquisition and other rights-relevant issues are not covered by franchise contracts

Higher-Risk Sectors

- Finance industry

- Law firms

- Mining industry

- Franchised food and beverage companies

- Construction industry

- Hospitality and restaurants

- Oil and Gas

- A variety of services provided in the context of large extractive industry projects, pipelines, energy projects, agribusiness and forestry projects that take place on indigenous and marginalized communities’ land around the world, in both developed and developing countries.

Questions for Leaders

- How does the company know whether and when the structure of its relationships with business partners may be reducing its ability to ensure that salient human rights risks are effectively managed?

- How does the company use its leverage at the point of structuring a relationship and defining the roles and responsibilities of different business partners to help ensure human rights risks will be well managed?

- How does the company discuss and make decisions about the viability of business partnerships where there is no evident way to mitigate salient human rights risks?

How to use this resource. ( Click on the “+” sign to expand each section. You can use the side menu to return to the full list of red flags, download this Red Flag as a PDF or share this resource. )

Understanding Risks and Opportunities

Risks to People

The way in which companies decide to structure their business relationships can have an effect on their ability to meet their human rights responsibilities. In particular, companies may routinely structure relationships in ways that limit their leverage over business partners.

Below are examples of ways in which companies structure relationships that may lead to a reduction in their ability to identify, prevent, mitigate and account for human rights impacts, or may reduce their perception of their responsibility to do so.

- In a syndicated loan, this may arise where the bank:

- relies on human rights due diligence conducted or commissioned by another participating bank in the syndicate;

- has little (direct) interaction with the E&S coordinating bank and/or the other participating banks on human rights impacts;

- has little interaction with stakeholders potentially affected by the project or those representing their interests

- has no influence over the creation or effective management of grievance mechanisms for affected stakeholders.

- In a JV partnership, this may arise where one party takes sole or primary responsibility for communication and dispute resolution with third parties, or where a company situates control over decisions on land and employment with the partner. This can be particularly problematic where the partner with this responsibility is an enterprise wholly or partially owned by a government that has a history of causing or ignoring impacts on vulnerable groups in the country, and the company has little practical leverage available to it.

- In a franchising relationship, this may arise where contracts retain franchisor control over businesses’ methods, procedures and standards, but not set out requirements on – nor accept responsibility for – rights-related issues such as employment practices, land acquisition, and environmental issues.

- In an advisory relationship, such as a lawyer-client relationship, this may arise where the advisor limits (or accept their client’s instructions to limit) their advice to exclude some or all potential impacts on human rights, at best closing the door to an important avenue for leverage held by advisors, and at worst playing a role in rendering it more likely that the client will impact rights through the relevant activities. (See related discussion on the role of the corporate legal advisor here).

In circumstances such as those above, a responsibility gap can emerge where neither business partner is engaged with addressing potential impacts, or where the contractual responsibility to do so is situated with a partner less able to do so. Further, a remedy gap emerges where neither business partner engages with grievances, impacting stakeholders’ right to remedy.

Risks to the Business

- Operational, Financial and Reputational Risks: A company’s understanding and implementation of its own responsibility in relation to impacts can be undermined when it structures a relationship in ways that limit its own scope for action and its accountability.

- For example, risks can arise where there are mistaken assumptions that due diligence conducted or commissioned by the E&S coordinating bank in a syndicated loan for project finance is sufficiently thorough. High profile examples of community conflict halting projects have highlighted that each financier is expected to know (and to show) that the HRDD conducted meets expectations: according to Banktrack, banks participating in the financing of the Dakota Access Pipeline “found themselves on the receiving end of the #DefundDAPL divestment campaign after the project violated Indigenous People’s rights – estimated to have cost them between US$8 and $20 billion in deposit withdrawals.”

- Legal Risks: The have been several lawsuits seeking to hold US company McDonald’s responsible for the treatment of franchise workers. In the United States the responsibility of franchisors to assume responsibility for employment conditions is a contested area. The company has stated that “franchisees are independent businesses that want to make their own decisions about hiring, pay and other matters.” Worker advocacy groups have “argued that many companies use contracting and franchising as ashield from responsibility for workers who make their business possible.” In 2020, a complaint was brought to the Dutch National Contact Point against McDonald’s on the basis that the company had not met OECD guidelines which “require due diligence by institutional shareholders in companies to ensure responsible business conduct.” The complainants alleged that due to “systemic sexual harassment” at franchised restaurants, the company had “neglected to act to create a safe workplace” for franchise employees.

- Business Opportunity Risks: Where advisors do not advise clients appropriately on the human rights risks associated with corporate decisions or activity, they risk losing repeat business when that advice proves inadequate in practice. The International Bar Association notes that:

- “There is growing recognition that a strong business case exists for respecting human rights and that the management of risks, including legal risks, increasingly means that lawyers, and particularly business lawyers, need to take human rights into account in their advice and services. The UNGPs are relevant to many areas of business legal practice, including but not limited to corporate governance, reporting and disclosure, litigation and dispute resolution, contracts and agreements, land acquisition, development and use, resource exploration and extraction, labour and employment, tax, intellectual property, lobbying, bilateral treaty negotiation, and arbitration.”

What the UN Guiding Principles say

*For an explanation of how companies can be involved in human rights impacts, and their related responsibilities, see here.

The parties to a business relationship may decide to allocate formal responsibilities in a particular way in their agreements – including responsibilities for identifying and addressing human rights risks. However, that does not remove them from any responsibility should human rights harms occur. For example, a company will still have a responsibility as a result of being linked to (and in some cases potentially contributing to) human rights impacts:

- In the context of a JV:

- whether it is a majority or minority stakeholder;

- whether or not it has primary responsibility for communication and dispute resolution with third parties;

- In the context of advice to clients:

- regardless of unilateral or agreed caveats with respect to what the advice does and does not address;

- In the context of syndicated loans for project finance:

- regardless of decisions on who will conduct/lead due diligence.

Similarly, a franchisor will still be linked (or potentially contributing) to impacts caused by franchisees vis-à-vis franchise employees.

Business relationships that are structured in these ways will typically affect the company’s ability to exercise leverage to mitigate human rights risks or impacts unless specific measures are included to address this. Where human rights impacts were foreseeable and the company still took on a role where its control or leverage was limited, this may be seen to suggest that the company contributed by omission to impacts caused by a business partner.

Possible Contributions to the SDGs

Where a company retains and uses leverage with business partners to strengthen respect for human rights, it can contribute to various SDGs. It may also build the capacity of its partners to contribute to the SDGs, by helping them understand and implement their own responsibilities, thereby contributing to:

SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals, in particular: Target 17.6 Enhance the global partnership for sustainable development, complemented by multi-stakeholder partnerships that mobilize and share knowledge, expertise, technology and financial resources, to support the achievement of the sustainable development goals in all countries, in particular developing countries. Target 17.17 Encourage and promote effective public, public-private and civil society partnerships, building on the experience and resourcing strategies of partnerships.

Taking Action

Due Diligence Lines of Inquiry

- Do we clearly communicate our human rights expectations to our partners?

- For joint ventures with significant human rights risks, do we ensure that legal and other agreements underpinning the ventures provide the necessary basis to ensure that human rights are respected in their operations? (See OHCHR and Business Dilemmas Forum)? For example:

- How do our agreements with partners allocate roles with relevance to the human rights of stakeholders, such as decisions on land,employment or dispute resolution with third parties?

- How do we ensure our partners carry out these roles in ways that respect human rights?

- Do we have pre-agreement on how human rights incidents and disputes will be dealt with, once they arise?

- Do we have the right to conduct audits of overall human rights compliance?

- Do we have the right to terminate the agreement in the event that human rights non-compliances are identified during such audits and are not rectified within a reasonable amount of time?

- How thorough are our due diligence procedures and do they include human rights risks? Do we tend to defer to or rely on processes of another partner without our own investigations? Are we prohibited from making contact with stakeholders by our agreements with business partners? How do we identify gaps between others’ processes and international human rights standards? How do we address these gaps? Do we look for early opportunities (e.g. at point of market entry) to create leverage? Do we include a leverage mapping into our due diligence procedure?

- Does the structure or duration of the relationship significantly limit our leverage?

- Do we have or participate in an effective grievance mechanism through which affected persons can raise human rights issues related to our partners’ activities?

- Do our agreements with partners contain confidentiality or consent requirements that constrain our ability to disclose information about our operations in higher risk areas? If so how do we ensure that stakeholders have access to information relevant to understanding how they may be affected and to claiming their rights?

Mitigation Examples

*Mitigation examples are current or historical examples for reference, but do not offer insight into their relative maturity or effectiveness.

There are numerous examples of a company seeking to influence the behavior of a business partner, including where that partner has primary responsibility for areas that impact rights.

(The following anonymized examples are adapted from Shift’s publication, Using Leverage in Business Relationships to Reduce Human Rights Risks).

- Shadowing Partners: A company has shadowed a joint venture partner as it conducted a stakeholder engagement.

- Seconding Staff: A company has seconded staff to a JV operation to lead on community relations and/or human rights risk management.

- Shared Audits: A company has conducted an internal audit of its own human rights performance at an operation, and shared results with key business partners, with an invitation/ offer to collaborate with them on addressing shared challenges, as well as on future such audits.

In the context of syndicated loans, responsible banks individually evaluate projects or borrowers against their own human rights and project-specific policies, including to address gaps between standards applied by the E&S (environment and social) coordinating bank and expectations under the UN Guiding Principles. Even where a bank has a smaller ticket in a syndicated loan, recognized expertise in the field of social impacts has allowed such banks to exert outsize leverage with other participating banks to ensure potential social impacts are adequately considered and addressed.

- Contract Provisions: Companies have negotiated various human rights-related provisions in contracts with business partners that created leverage later in the relationship. Examples include contract provisions that:

- set out a commitment to meet certain standards (e.g., Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights, IFC Performance Standards);

- give the company (even when a junior partner) the lead in managing human rights-related issues or in staffing the community relations function at an extractive project;

- require a higher voting majority of the board on human rights-related issues.

- Company Policies and Code of Conducts: Companies have negotiated the inclusion of references to their own standards or policies in joint agreements, such as a Code of Conduct or policies on security. In the context of non-operated joint ventures, Total reports that it “make[s] ongoing efforts so that the operating party applies equivalent principles to ours.”

- Multi-stakeholder (Industry) Initiatives (MSIs) with Human Rights Commitments: A company may require or suggest that a partner join a credible multi-stakeholder (industry) initiative, or may jointly join an initiative with them: for example, PNG and FGB jointly joined the FLA in furtherance of “a desire to drive long-term change in the palm oil supply chain for the industry as a whole.” Companies have [also] highlighted partners’ existing commitments – including those made in the context of MSIs – when seeking to exert leverage to bring the partner’s attention to addressing impacts.

- Introducing a Non-Essential Partner with Strong Standards: Companies have involved the International Finance Corporation as a small percentage financier of a project, so they could reference their Performance Standards in project contracts and in broader discussions with project partners.

- Strategic Role: Some companies identify the committees with oversight of areas likely to be associated with salient human rights impacts associated with a joint venture (e.g. health and safety; procurement or sustainability), and ensure they play a strategic role in them, even when they are a minority partner.

- Capacity Building: A company may extend training and other capacity and awareness building activities to partners and/or industry players to enhance and to bolster the likelihood of their conducting adequate human rights due diligence.

Alternative Models

There may be opportunities for increasing leverage to address actual and potential human rights impacts in a joint venture context through a coordinated approach. For example, in 2016 BHP created the Non-Operated Joint Ventures (NOJV) Asset within Minerals Americas in order to establish effective engagement with its joint venture partners and companies in line with BHP’s Charter. The Asset creates a single point of accountability with responsibility for all non-operated joint ventures in Minerals Americas and its purpose includes having transparency over JV companies’ risks and opportunities, in an active feedback process, whilst maintaining the JV company’s management independence.

Other tools and resources

General:

- Shift (2015) Human Rights Due Diligence in High Risk Circumstances: Practical Strategies for Businesses: highlights strategies and practices that certain businesses have found most effective when conducting human rights due diligence in high risk circumstances. It includes “higher risk business relationships” such as those with business partners.

- Shift (2013) Using Leverage in Business Relationships to Reduce Human Rights Risks addresses various business relationships, including joint ventures.

Joint Ventures:

- IHRB (2012) Chapter 5: Respect for Human Rights in Joint Ventures Relationships of State of Play – Human Rights in Business Relationships: assists, inter alia, with identification and mitigation of human risks arising in connection with JV partners.

Finance:

Project Finance:

- Shift (2018) Enhancing the Alignment of the Equator Principles with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights: A Public Summary of Shift’s Advice to the Equator Principles Association.

- Equator Principles (2020) Equator Principles EP4.

- Equator Principles (2020) Guidance note on Implementation of human rights assessments under the Equator Principles.

- Equator Principles (2020) Guidance note on evaluating projects with affected indigenous peoples.

Corporate Lending:

- IRBC Agreements, The Dutch Banking Sector Agreement (2019) DBA’s Analysis of Severe Human Rights Issues in the Palm Oil Value Chain and Follow-up actions.

- IRBC Agreements, The Dutch Banking Sector Agreement (2019) Increasing leverage working group: Progress report phase I working group paper.

Legal Advice:

- International Bar Association (2016) Practical Guide on Business and Human Rights for Business Lawyers and Business and Human Rights Guidance for Bar Associations.

- A4ID, The UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights: A guide for the legal profession: provides an analysis, with case examples, of:

- a law firms’ implementation of rights and responsibilities in client relationships;

- the relationship between the UNGPs and codes of professional conduct for the legal profession.

- IBA, Handbook for company and commercial lawyers on Business and Human Rights: about the links between different kinds of risks (drafted with help and advice from practitioners from some big law firms).

- UN Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner (2011) Principles for responsible contracts: Integrating the management of human rights risks into state-investor contracts.

Citation of research papers and other resources does not constitute an endorsement by Shift of their conclusions.

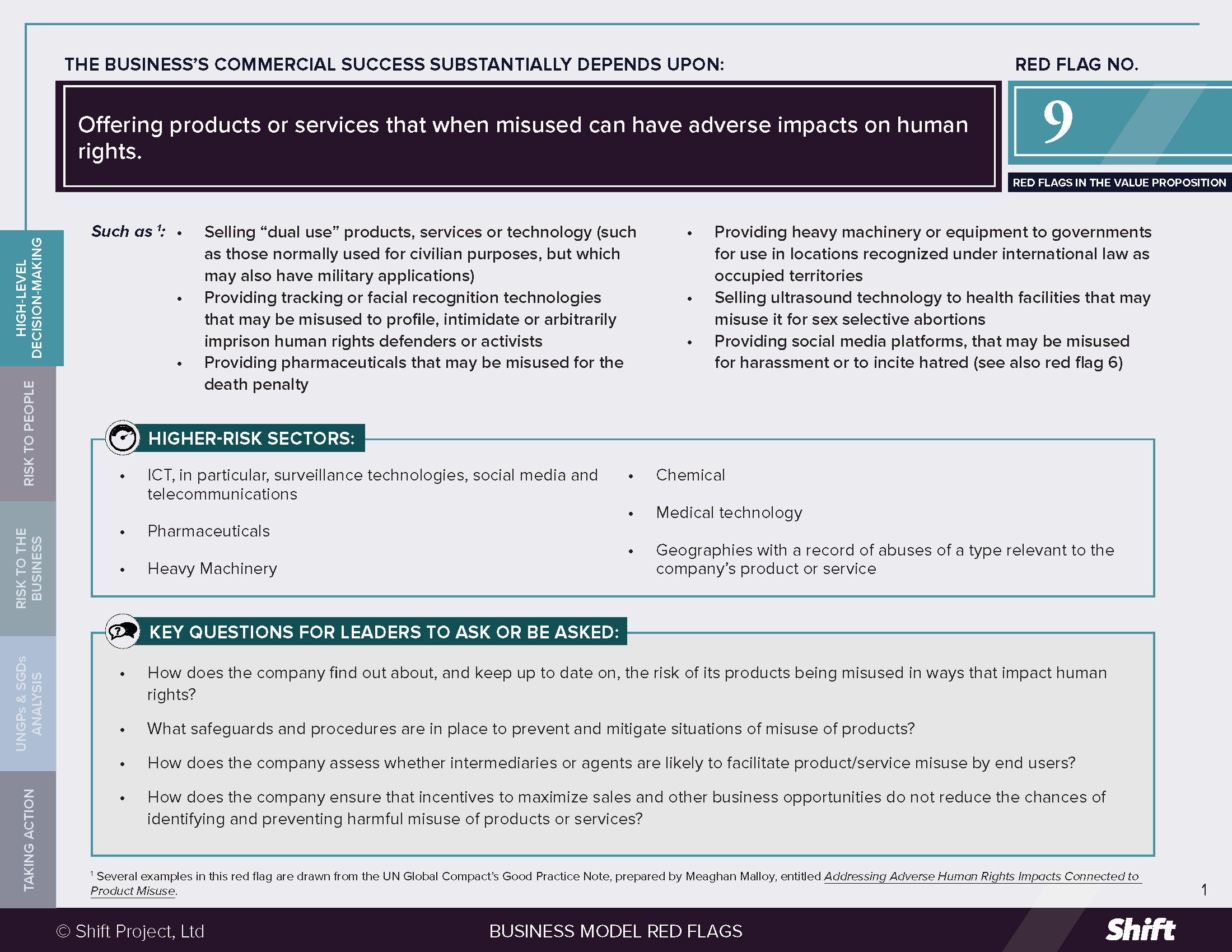

Red Flag 9. Products that harm when misused

RED FLAG # 9

Offering products or services that when misused can have adverse impacts on human rights.

For Example

(

Several examples in this Red Flag are drawn from the UN Global Compact’s Good Practice Note, prepared by Meaghan Malloy, entitled, Addressing Adverse Human Rights Impacts Connected to Product Misuse.

)

- Selling “dual use” products, services or technology (such as those normally used for civilian purposes, but which may also have military applications)

- Providing tracking or facial recognition technologies that may be misused to profile, intimidate or arbitrarily imprison human rights defenders or activists

- Providing pharmaceuticals that may be misused for the death penalty

- Providing heavy machinery or equipment to governments for use in locations recognized under international law as occupied territories

- Selling ultrasound technology to health facilities that may misuse it for sex selective abortions

- Providing social media platforms, that may be misused for harassment or to incite hatred (see also Red Flag 6)

Higher-Risk Sectors

- ICT, in particular, surveillance technologies, social media and telecommunications

- Pharmaceuticals

- Heavy Machinery

- Chemical

- Medical technology

- Geographies with a record of abuses of a type relevant to the company’s product or service

Questions for Leaders

- How does the company find out about, and keep up to date on, the risk of its products being misused in ways that impact human rights?

- What safeguards and procedures are in place to prevent and mitigate situations of misuse of products?

- How does the company assess whether intermediaries or agents are likely to facilitate product/service misuse by end users?

- How does the company ensure that incentives to maximize sales and other business opportunities do not reduce the chances of identifying and preventing harmful misuse of products or services?

How to use this resource. ( Click on the “+” sign to expand each section. You can use the side menu to return to the full list of red flags, download this Red Flag as a PDF or share this resource. )

Understanding Risks and Opportunities

Risks to People

- Risks to people are heightened by the nexus between products that are vulnerable to misuse and sales to entities likely to misuse them.

- Interviews with business and civil society representatives conducted by the UN Global Compact “underscored that one of the biggest challenges in conceptualizing product misuse as a human rights issue is the vast array of ways, including non-obvious ways, a product or service can be misused and inflict human rights harm.”

- Several examples are listed above and include severe impacts, such as:

- sale of pharmaceuticals misused for the administration of the death penalty (right to life; right to freedom from torture, cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment);

- sale of tracking or facial recognition technologies that may be misused to surveil civil society or arbitrarily imprison, e.g. ethnic or political groups. (Freedom from arbitrary arrest, detention or exile and/or freedom from torture and inhuman or degrading treatment).

Risks to the Business

- Reputational Risks: Links between well-known companies and the impacts of product misuse are more easily spread through the 24/7 news cycle and the sharing of incidents and photographs facilitated by mainstream and social media. During the Arab Spring, the role of Western Technology firms in “helping Arab dictators” was highlighted in US media. Popular opinion increasingly places some degree of responsibility on the companies concerned, and not just on those misusing the product or service, or on regulators.

- Financial Risks: These may include investor divestment or customer boycotts where companies are seen to be failing to address product misuse. In 2012, construction machinery company Caterpillar was removed from three MSCI indexes for factors including “an ongoing controversy associated with use of the company’s equipment in the occupied Palestinian territories.”

- Legal, Financial and Operational: Risks also arise, for example, where end users include repressive regimes. Blacklisting of Chinese technology companies by the US Government on the grounds of rights violations against Muslim minority groups in Xinjiang, China, disallows US companies from selling technology to these companies without a US government license. In 2019, Sony and Sharp faced scrutiny for the alleged supply of parts to a Chinese video surveillance company blacklisted by the United States over human rights violations of ethnic Uyghur people in the Xinjiang Autonomous Region of China. The blacklisted company had “previously stated on its website that it could identify members of the Uighur ethnic minority group.”

What the UN guiding principles say

*For an explanation of how companies can be involved in human rights impacts, and their related responsibilities, see here.

This red flag arises in two distinct situations, namely where the business relies on:

- sales to a known commercial customer where there is a likelihood it will misuse the product in ways that have human rights impacts, or sell it onwards to an end-user who misuses the product

- sale of a product or service to the general public, where there is recognized misuse by a minority.

With regards to scenario a), Guiding Principle 13(b) states that businesses should “seek to prevent or mitigate adverse human

rights impacts that are directly linked to their operations, products or services by their business relationships, even if they have not contributed to those impacts.” Business relationships include relationships with commercial customers, and as such, a company may be directly linked to an impact caused by commercial customers in the course of using the product or service.

In certain circumstances, product misuse by a commercial customer may involve a situation of contributing to harm where a company knows of the risk or fact of its products being misused, and does nothing to address the situation. The UN Global Compact describes a scenario in which a company sets up a shell company in order to hide the fact that it is selling surveillance technology to repressive governments. If the company knew or should have known that the governments concerned were likely to use the product to impact human rights, yet proceeded with a sale that enables this, it may be considered to contribute to any harm suffered.

In scenario b), the scope of the company’s human rights responsibility includes the safety of people using its products, even if they are not the intended user. As such, if the company is – or should be – aware of a potential negative impact associated with its products, a failure to adapt the product or otherwise seek to minimize the risk of the impacts occurring (e.g. through terms and conditions of use, warnings on packaging or instructions etc.) could place the company in a situation of causing an impact, or, where the impact on a third party is caused by a consumer misusing its products, contributing to the impact.

Possible contributions to the SDGs

Addressing impacts to people associated with this red flag indicator can contribute to a range of SDGs depending on the industry and impact concerned, for example:

SDG 3: Good Health and Well-Being.

SDG 9: Industry, innovation and infrastructure, in particular Target 9.1: Develop quality, reliable, sustainable and resilient infrastructure, including regional and transborder infrastructure, to support economic development and human well-being, with a focus on affordable and equitable access for all.

SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities, in particular Target 10.2: By 2030, empower and promote the social, economic and political inclusion of all, irrespective of age, sex, disability, race, ethnicity, origin, religion or economic or other status.

SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities, in particular Target 11.3: By 2030, enhance inclusive and sustainable urbanization and capacity for participatory, integrated and sustainable human settlement planning and management in all countries.

SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production.

SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions, in particular Target 16.1: Significantly reduce all forms of violence and related death rates everywhere. Target 16.6: Develop effective, accountable and transparent institutions at all levels. Target 16.7: Ensure responsive, inclusive, participatory and representative decision-making at all levels.

Taking Action

Due Diligence Lines of Inquiry

- How do we assess the potential risk of product misuse? How do we understand and address the ways in which “specific variables in design, components or materials used, and markets and customers targeted” may lead to product misuse resulting in human rights impacts?