The PTF-ESRS announced the signing of a Statement of Cooperation with Shift. Both organizations will put together their experience and expertise to encourage the swift development of European sustainability reporting standards in the social domain and at the same time the progress of converged standards at international level. Each organization will contribute to key technical projects of its counterpartin the social domain.

Archives: Resources

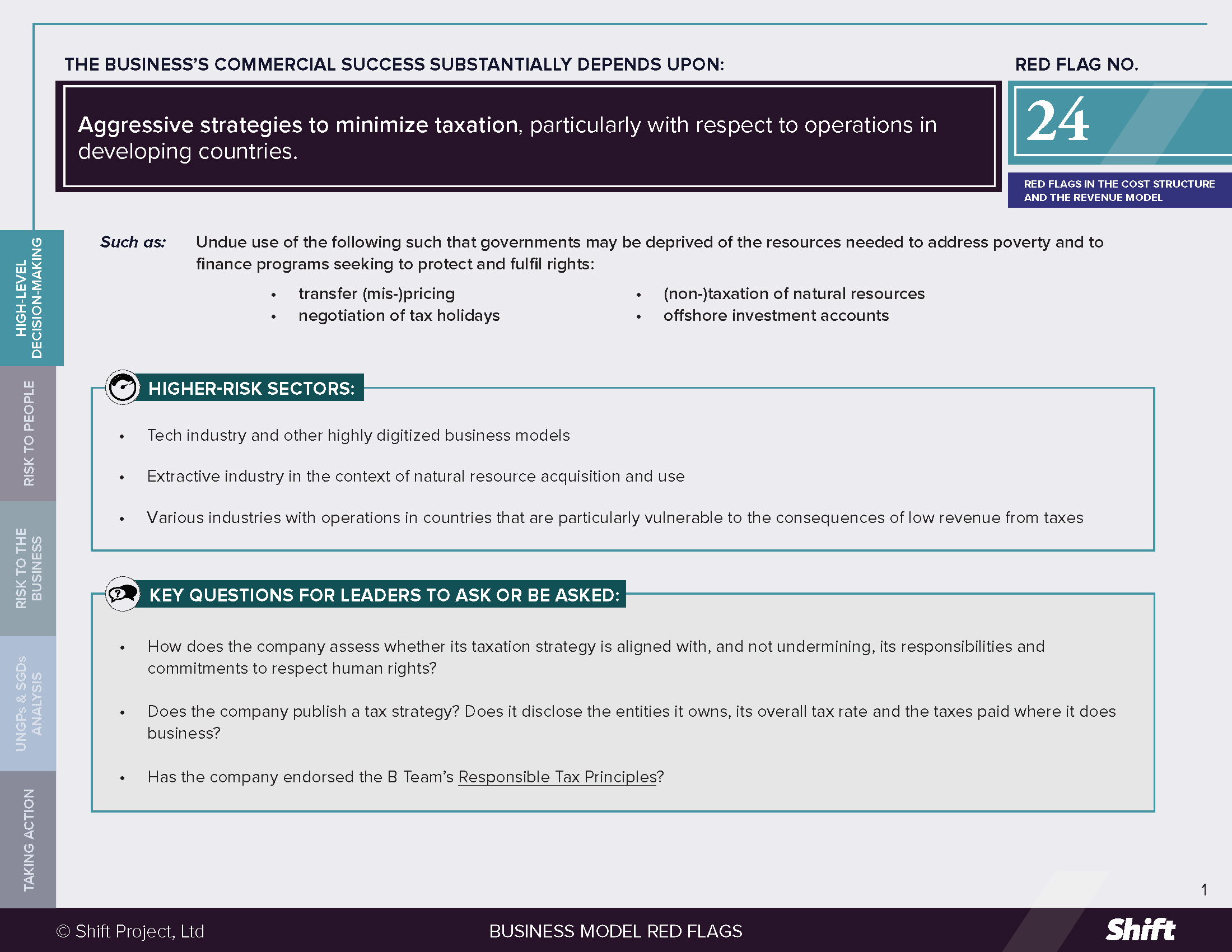

Red Flag 24. Aggressive tax-minimization strategies

RED FLAG # 24

Aggressive strategies to minimize taxation, particularly with respect to operations in developing countries.

For Example

Undue use of the following such that governments may be deprived of the resources needed to address poverty and to finance programs seeking to protect and fulfil rights:

- transfer (mis-)pricing

- negotiation of tax holidays

- (non-)taxation of natural resources

- offshore investment accounts

Higher-Risk Sectors

- Tech industry and other highly digitized business models

- Extractive industry in the context of natural resource acquisition and use

- Various industries with operations in countries that are particularly vulnerable to the consequences of low revenue from taxes

Questions for Leaders

- How does the company assess whether its taxation strategy is aligned with, and not undermining, its responsibilities and commitments to respect human rights?

- Does the company publish a tax strategy? Does it disclose the entities it owns, its overall tax rate and the taxes paid where it does business?

- Has the company endorsed the B Team’s Responsible Tax Principles?

How to use this resource. ( Click on the “+” sign to expand each section. You can use the side menu to return to the full list of red flags, download this Red Flag as a PDF or share this resource. )

Understanding Risks and Opportunities

Risks to People

- The International Bar Association’s Human Rights Institute (IBA-HRI) found that in the context of the developing world, tax practices considered most relevant to potential human rights impacts include transfer-pricing and other cross-border intra-group transactions (see Lipsett). Multi-national enterprises may “take advantage of gaps in the interaction of different tax systems to artificially reduce taxable income or shift profits to low-tax jurisdictions in which little or no economic activity is performed” (see OECD). The Task Force also identified the following as areas of greatest concern: the negotiation of tax holidays and incentives, the taxation of natural resources, the use of offshore investment accounts and, finally, secrecy jurisdictions due to their role in facilitating tax abuses. (See Lipsett).

- Highly digitized business models have been associated with challenges to existing taxation frameworks, including where the business is highly involved in the economic life of a jurisdiction without any significant physical presence, as well as where a high number of assets are intangible (such as algorithms and software). (See OECD).

- Aggressive taxation practices such as those identified above can “deprive governments of the resources required to provide the programmes that give effect to economic, social and cultural rights, and to create and strengthen the institutions that uphold civil and political rights.” (See Lipsett). Lost revenue from taxation can lead to decreased funds available for spending on “services such as health, education, housing, access to water and other human rights.” It has been noted that countries in the global south lose much more money to tax evasion and illicit financial flows than they receive in international aid.

- The connection between tax and inequality has been explored by the IBA-HRI, which has noted that “the global shadow economy is contributing to a growth in global inequality, which is also having a major impact on democracy.”

Risks to the Business

- Reputational Risks: “Over recent years, the tax affairs of major businesses have been subject to unprecedented levels of scrutiny, debate and controversy.” The FT, has noted that despite the “dry, complex nature of corporate tax planning,” campaigners have begun to focus on the issues with “zeal.”

- Regulatory Risks: Concerns over the facilitation of base erosion and profit shifting through uneven legislation has led to a multilateral international tax policy initiative under the OECD, resulting in a multilateral convention, the sharing of information between tax administrations, disclosure of previously secret tax rulings and “legislative changes made to amend/abolish 110+ [‘harmful preferential tax regimes’].”

- Operational Risks: Public outcry over taxation inequality has “contributed to significant political instability in many developing countries” which has also been to the detriment of companies operating in these areas. Such outcry has not been limited to developing countries: in the UK several companies have appeared before the Public Accounts Committee or had their high street stores occupied by protestors, and US companies have been the subject of major news investigations.

- Legal, Financial and Operational: Risks also arise where public outcry leads to a re-examination of tax settlements. Calvert Investments, referencing the International Accounting Standards Board, has noted: “Reputational damage [from a perception that a company is not paying its fair share of tax to a host country] may lead to liabilities for external costs associated with a company’s operations, greater difficulty in permitting that could lead to project delays or cancellation or the loss of favourable tax status or other forms of government financial assistance.”

What the UN Guiding Principles say

*For an explanation of how companies can be involved in human rights impacts, and their related responsibilities, see here.

- The “corporate responsibility to respect,” the second pillar of the UNGPs, “exists independently of States’ abilities and/or willingness to fulfil their own human rights obligations, and … exists over and above compliance with national laws and regulations protecting human rights.” (Principle 11, Commentary). In other words, “all business enterprises have the same responsibility to respect human rights wherever they operate” (Principle 23, Commentary), whether or not they have a domestic legal obligation to do so. As such, undue or aggressive use of taxation strategies may infringe companies’ responsibility even where actions are legal under local taxation laws.

- The UNGPs note that companies should “strive for coherence between their responsibility to respect human rights and policies and procedures that govern their wider business activities …” (Principle 16, Commentary), which would be relevant where aggressive tax strategies undermine efforts to respect rights in jurisdictions of operation.

- Where a company is benefiting from an unduly aggressive tax strategy or unusually generous taxation deal in a particular location, it may be directly linked to impacts that result from a lack of public services for local populations. Where it is aware of this situation and does nothing, it may be judged to contribute to such impacts. This may be a contribution in parallel with other companies benefiting from similar tax arrangements, such that they collectively deplete state revenues needed to fulfil people’s human rights. If the company lobbies in favor of tax deals that undercut state revenues with similar results, it may be seen as contributing by incentivizing the government to favor corporate benefits over the human rights of the population.

- The connection between taxation planning and human rights is complex, but receiving increased attention. Mauricio Lazala, Deputy Director of the Business and Human Rights Resource Centre has noted that “[t]he State duty to protect human rights in its corporate tax policies, the business responsibility to respect human rights and carry out due diligence in their tax practices, and the need for effective remedy for tax abuse are all relevant, yet still emerging dimensions of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.”

Possiblr Contributions to the SDGs

Taxation policy is a key element in facilitating the achievement of the SDGs. As such, this red flag indicator is relevant for a range of SDGs, including:

SDG 1: No Poverty, including Target 1.2: By 2030, reduce at least by half the proportion of men, women and children of all ages living in poverty in all its dimensions according to national definitions. The IBA-HRI has noted that “greater tax revenues have the potential to reduce poverty, provided that they are properly spent on programmes that contribute to infrastructure, development and human rights.” (See IBA-HRI p.89).

SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities, in particular Target 10.4: Adopt policies, especially fiscal, wage and social protection policies, and progressively achieve greater equality. Income redistribution through taxation can contribute to reducing inequality and promoting inclusive growth.

SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals, in particular Target 17.1: Strengthen domestic resource mobilization, including through international support to developing countries, to improve domestic capacity for tax and other revenue collection.

Taking Action

Due Diligence Lines of Inquiry

- Do we have a policy on tax planning that includes a human rights perspective? Do we have a considered and disclosed position on use of “tax havens”?

- How transparent are we about our taxation strategy including as regards our operations in developing countries? Do we disclose how our approach to taxation planning aligns with our business purpose and sustainability strategy?

- To what extent do we review the structures and practices of tax planning through the lens of our responsibility respect human rights, (rather than merely the amount of tax paid, which is an outcome of these practices).

- Are we involved in projects for which tax rules are being created? Is our approach to these negotiations aligned with our sustainability commitments/ responsibilities?

- How meaningful is the interaction between our departments and external advisors responsible for taxation strategy and our corporate responsibility/ sustainability/ human rights teams, with a view to internal alignment?

Mitigation Examples

*Mitigation examples are current or historical examples for reference, but do not offer insight into their relative maturity or effectiveness.

- Allianz states that it “seeks to be a responsible tax payer… Our attitude is that tax planning is not a goal in itself, but should be undertaken to support the business strategy while being both tax-efficient and legally compliant.” (Ralf Chalupnik, Director of Tax Policy, Allianz, in B Team: “A New Bar for Responsible Tax”). The company reports that it does “not engage in aggressive tax planning or artificial structuring that lacks business purpose or economic substance,” does not use tax havens and “refrain[s] from discretionary tax arrangements.” Allianz has a comprehensive “Standard for Tax Management” which requires that tax planning be based on valid business reasons.

- Unilever reports on its “total tax rate” in its annual report “which they see as a key indicator that they pay tax on 100% of their profits aligned to the countries where they do business.” Vodafone has published an annual tax report setting out their total contribution to public finances, country- by-country, on an actual cash-paid basis, since 2013; Maersk began to include taxation in their sustainability report in 2016 and have conducted a gap analysis against the B Team Responsible Tax Principles, aiming for implementation in 2020. (From B Team: “A New Bar for Responsible Tax”).

- The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) is a coalition of governments, companies and civil society working “to improve openness and accountable management of revenues from natural resources.”

Alternative Models

In 2012 Starbucks announced that following “loud and clear” messages from customers, the company would make “changes which will result in Starbucks paying higher corporation tax in the UK – above what is currently required by law.”

Other Tools and Resources

- The B Team’s Responsible Tax Principles were developed through dialogue with a group of leading companies, convened by The B Team with contributions from civil society, institutional investors and international institution representatives.

- The International Bar Association’s Human Rights Institute released a 2013 report entitled Tax Abuses, Poverty and Human Rights. The Report addresses tax abuses from the novel perspective of human rights law and policy. It is based on extensive consultation from diverse perspectives and offers insight into the links between tax abuses, poverty and human rights.

- The Business and Human Rights Resource Centre portal on Tax Avoidance.

- Oxfam (2017) Making Tax Vanish: How the practices of consumer goods MNC RB show that the international tax system is broken. Contains an in-depth analysis and critique of the taxation planning practices of one company as well as the company’s response.

- M Lazala, Business & Human Rights Resource Centre (2015) Tax avoidance: the missing link in business & human rights?

- Tax Justice Network is a UK-based international research and advocacy network focusing on the link between taxation and, inter alia, human rights. It publishes the Corporate Tax Haven Index.

- OECD (2019) Tax and Digitalization discusses the tax challenges that arise from digitalization in furtherance of a work program to culminate in 2020 with an agreed global, long-term solution.

- The OECD’s Tax portal includes its Action Plan on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting and Inclusive Framework.

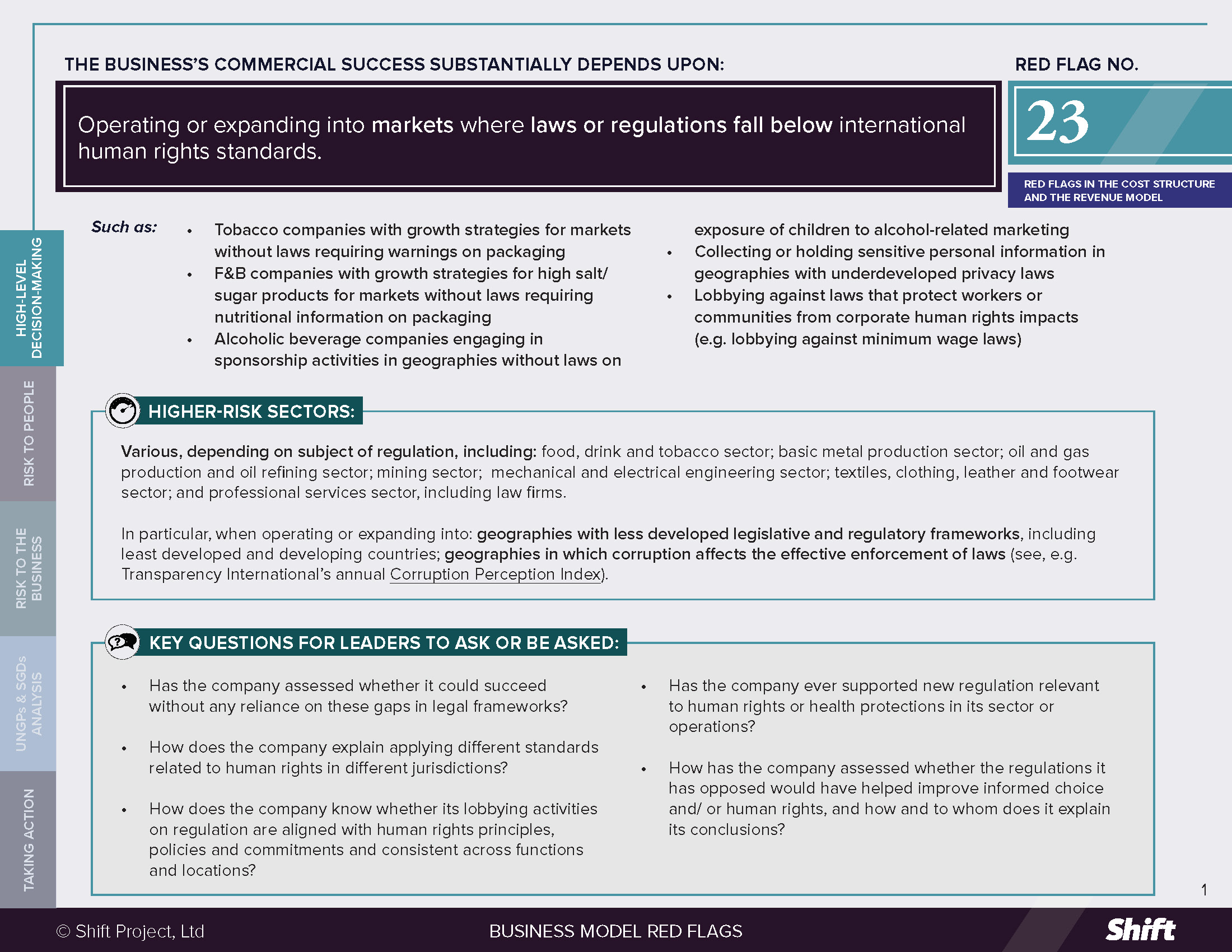

Red Flag 23. Markets where regulations fall below human rights standards

RED FLAG # 23

Operating or expanding into markets where laws or regulations fall below international human rights standards.

For Example

- Tobacco companies with growth strategies for markets without laws requiring warnings on packaging

- F&B companies with growth strategies for high salt/ sugar products for markets without laws requiring nutritional information on packaging

- Alcoholic beverage companies engaging in sponsorship activities in geographies without laws on exposure of children to alcohol-related marketing

- Collecting or holding sensitive personal information in geographies with underdeveloped privacy laws

- Lobbying against laws that protect workers or communities from corporate human rights impacts (e.g. lobbying against minimum wage laws)

Higher-Risk Sectors

Various, depending on subject of regulation, including: food, drink and tobacco sector; basic metal production sector; oil and gas production and oil refining sector; mining sector; mechanical and electrical engineering sector; textiles, clothing, leather and footwear sector; and professional services sector, including law firms.

In particular, when operating or expanding into: geographies with less developed legislative and regulatory frameworks, including least developed and developing countries; geographies in which corruption affects the effective enforcement of laws (see, e.g. Transparency International’s annual Corruption Perception Index).

Questions for Leaders

- Has the company assessed whether it could succeed without any reliance on these gaps in legal frameworks?

- How does the company explain applying different standards related to human rights in different jurisdictions?

- How does the company know whether its lobbying activities on regulation are aligned with human rights principles, policies and commitments and consistent across functions and locations?

- Has the company ever supported new regulation relevant to human rights or health protections in its sector or operations?

- How has the company assessed whether the regulations it has opposed would have helped improve informed choice and/ or human rights, and how and to whom does it explain its conclusions?

How to use this resource. ( Click on the “+” sign to expand each section. You can use the side menu to return to the full list of red flags, download this Red Flag as a PDF or share this resource. )

Understanding Risks and Opportunities

Risks to People

Where the business model is substantially dependent on gaps in legal frameworks, the company may engage in:

- Practices associated with maintaining this business model feature risk perpetuating a “race to the bottom,” as countries compete with lower regulatory standards to attract corporate investment.

- Lobbying against measures or laws that protect people from human rights impacts, for example lobbying against:

- (increased) minimum wage laws, affecting, inter alia, the right to just and favorable conditions of work, including decent remuneration;

- Indigenous title to land affecting, inter alia, Indigenous people’s rights;

- restrictions on emissions into land, sea and air, affecting the right to an adequate standard of living;

- laws that support informed choice, affecting the right to health.

- Legal strategies that prevent the state from protecting people from human rights impacts (potentially various), for example:

- seeking to use investment treaties (including stabilization clauses) to limit states’ abilities to enact or amend legislation or regulations that increase human rights protection;

- seeking to enforce intellectual property rights against public health imperatives.

Risks to the business

- Reputational and Operational: risks arise due to inconsistencies between what the company says in public and in private regarding regulatory protections, and in what it does in different parts of the world based on different levels of regulatory protection. Reputations may also be open to attack where the company invests considerable resources in weakening human rights protections.

- Legal and Financial Risk: where a company mounts an unsuccessful legal challenge to government regulation aimed at public protection, it may face financial penalties. For example, tobacco company Philip Morris was ordered to pay the Australian government millions of dollars after unsuccessfully suing the nation over its plain-packaging laws.

- Financial Risks: can arise where investors consider companies’ attempts to influence public policy in their investment decisions. For example, US-based Trillium Asset Management reportedly monitors the levels and recipients of corporate giving, corporate policies on political contributions and membership of industry (lobbying) associations as part of their background research for stock selection in their socially responsible investment funds.

- Business Continuity Risks: where business contributes to the degradation of resources or people on which the business relies, e.g. by lobbying against laws that protect consumers or the community or limit environmental degradation.

What the UN Guiding principles say

*For an explanation of how companies can be involved in human rights impacts, and their related responsibilities, see here.

- Under the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, the corporate responsibility to respect human rights “exists independently of States’ abilities and/or willingness to fulfil their own human rights obligations, and … exists over and above compliance with national laws and regulations protecting human rights.” (Principle 11, Commentary) In other words, “all business enterprises have the same responsibility to respect human rights wherever they operate” (Principle 23, Commentary), whether or not they have a domestic legal obligation to do so. As such, adopting an inherently uneven, compliance-based approach risks breaching the company’s responsibility in places where laws do not meet internationally accepted human rights standards.

- The UNGPs note that companies should, “strive for coherence between their responsibility to respect human rights and policies and procedures that govern their wider business activities and relationships [including] …. lobbying activities where human rights are at stake.” (Principle 16, Commentary).

- Where the company actively lobbies against or takes action to constrain laws that have the practical effect of furthering respect for human rights, it risks contributing to human rights impacts, whether as a sole contributor or as a result of the aggregate contribution of several actors.

- Where a company is benefiting from an absence of protection of rights in the countries where it operates, it may be directly linked to impacts; where it is aware of this and does nothing, it may, depending on a number of factors, be considered to be contributing to the impacts.

Possible Contributions to the SDGs

Addressing impacts on people associated with this red flag indicator can contribute to a range of SDGs depending on the impact concerned, for example:

SDG 3: Good Health and Well Being, in particular Target 3.5: strengthen the prevention and treatment of substance abuse, including narcotic drug abuse and harmful use of alcohol; and Target 3.10: strengthen the implementation of the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control in all countries, as appropriate.

SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth, in particular Target 8.5: by 2030, achieve full and productive employment and decent work for all women and men, including for young people and persons with disabilities, and equal pay for work of equal value.

SDG 16: Peace, justice and strong institutions, in particular Target 16.7: ensure responsive, inclusive, participatory and representative decision-making at all levels; and Target 16.10: ensure public access to information and protect fundamental freedoms, in accordance with national legislation and international agreements.

Taking Action

Due Diligence Lines of Inquiry

- What legal frameworks are we actively seeking, supporting or opposing in order to execute our strategy? E.g. what regulatory drivers determine our entry into or exit from a sourcing location or sales market? How do these legal frameworks (or relevant elements) map against gaps in human rights protections?

- Do we have a policy on when and how we will lobby against regulatory initiatives that include provisions aimed at increasing consumer access to information about their health choices or at protecting other human rights?

- Have we assessed whether and to what extent our engagements with governments on regulatory developments are in line with our responsibility to respect human rights and enable governments to introduce human rights protections? Have we examined our lobbying activities in light of our own human rights commitments and strategies?

- Do our government affairs team engage routinely with our corporate responsibility/ sustainability/ human rights teams, with a view to internal alignment?

- Where we use external lobbying organizations, are our corporate responsibility/ sustainability/ human rights team consulted on the terms of their mandate?

- Do we disclose our position on key public policy issues? Do we reveal our external memberships, donations and methods of influence? If not, why not?

Mitigation Examples

*Mitigation examples are current or historical examples for reference, but do not offer insight into their relative maturity or effectiveness.

Applying purpose and principles to lobbying activities:

- In 2017 Campbell’s Soup withdrew from the Grocery Manufacturers Association citing “our purpose and principles,” including positions on food labelling. When the United States Food and Drug Administration agreed to extend a deadline for food and beverage companies’ to introduce a “Nutrition Facts Panel,” the company announced it was “continuing to strive to meet the original deadline.”

- The CEO Water Mandate’s Guide to Responsible Business Engagement with Water Policy (2010) contains “Principles for Responsible Water Policy Engagement.” Principles 1 and 2 provide that “responsible corporate engagement in water policy must be motivated by a genuine interest in furthering efficient, equitable, and ecologically sustainable water management” and that companies should ensure “that activities do not infringe upon, but rather support, the government’s mandate and responsibilities to develop and implement water policy…”.

Contributing to a regulatory environment that enables respect for rights:

- Oil and gas companies have jointly pressed a government to improve transparency requirements before proceeding with bids for concessions, in order to level the playing field and avoid human rights performance becoming a competitive issue. (See Shift’s Using Leverage guide at p. 22).

- In 2014, eight apparel brands wrote to the Cambodian deputy prime minister and the chairman of the local Garment Manufacturers Association to say they were “ready to factor higher wages” into their pricing.

Alternative Models

Companies striving to ensure a living wage across their operations and supply chain seek to mitigate the effects of operations in countries in which there is no, or an inadequate, minimum wage. ACT (Action, Collaboration, Transformation) is an “agreement between global brands and retailers and trade unions to transform garment, textile and footwear industry and achieve living wages for workers through collective bargaining at industry level linked to purchasing practices.” Through industry-level collective bargaining in sourcing countries, companies seek to avoid competing with each other based on lower wages (and regulations that enable this), but rather on other factors.

Other tools and Resources

- Business for Social Responsibility (2019) Human Rights Policy Engagement: The Role of Companies: a BSR report on a human rights-supportive approach to public policy engagement.

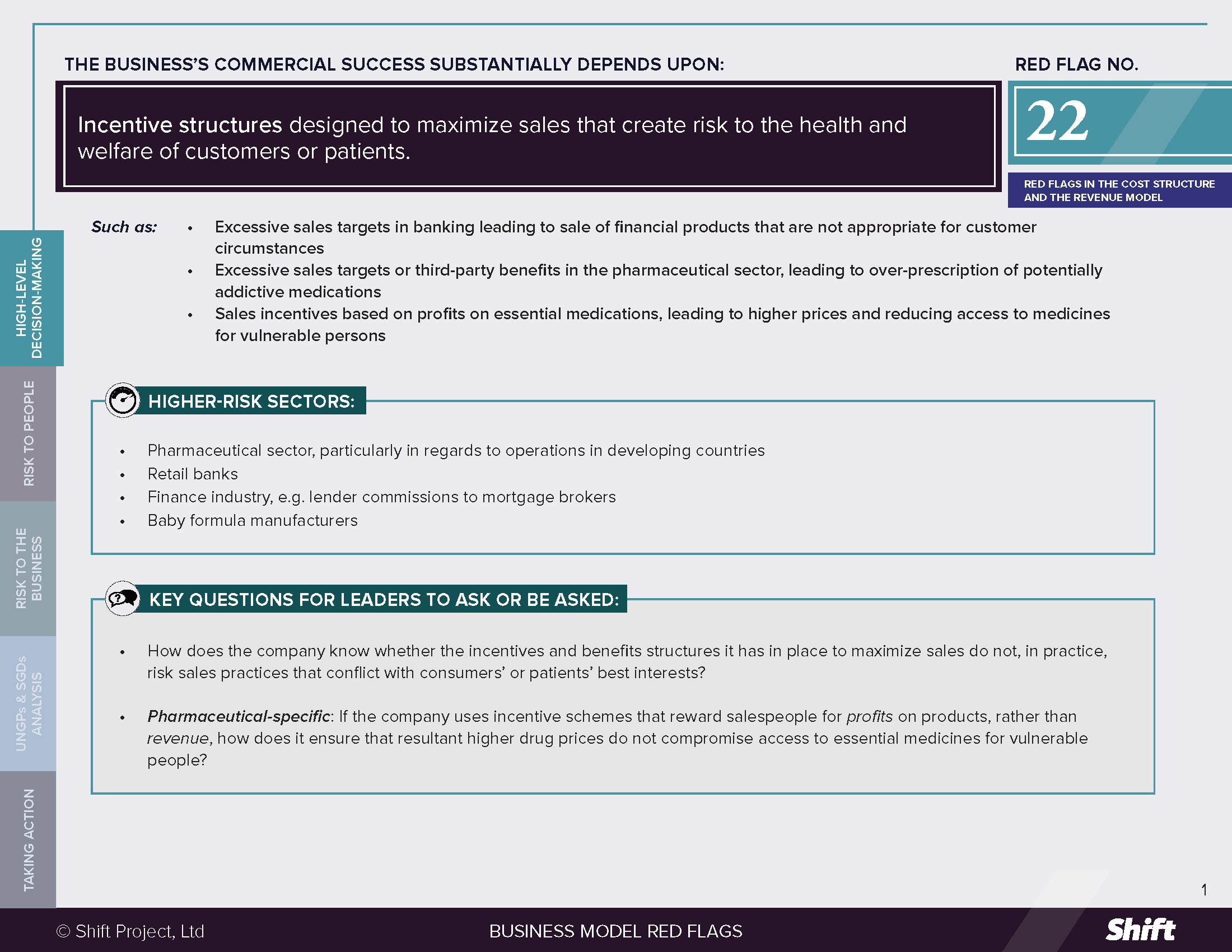

Red Flag 22. Sales-maximizing incentives that put consumers at risk

RED FLAG # 22

Incentive structures designed to maximize sales that create risk to the health and welfare of customers or patients.

For Example

- Excessive sales targets in banking leading to sale of financial products that are not appropriate for customer circumstances

- Excessive sales targets or third-party benefits in the pharmaceutical sector, leading to over-prescription of potentially addictive medications

- Sales incentives based on profits on essential medications, leading to higher prices and reducing access to medicines for vulnerable persons

Higher-Risk Sectors

- Pharmaceutical sector, particularly in regards to operations in developing countries

- Retail banks

- Finance industry, e.g. lender commissions to mortgage brokers

- Baby formula manufacturers

Questions for Leaders

- How does the company know whether the incentives and benefits structures it has in place to maximize sales do not, in practice, risk sales practices that conflict with consumers’ or patients’ best interests?

- Pharmaceutical-specific: If the company uses incentive schemes that reward salespeople for profits on products, rather than revenue, how does it ensure that resultant higher drug prices do not compromise access to essential medicines for vulnerable people?

How to use this resource. ( Click on the “+” sign to expand each section. You can use the side menu to return to the full list of red flags, download this Red Flag as a PDF or share this resource. )

Understanding Risks and Opportunities

Risks to People

Incentive and benefit structures, a key component of the sales promotion strategy of many companies, are designed to reward salespeople for revenue generated for the business. However, such structures can lead to negative outcomes for people where targets are excessively high, practices are subject to inadequate oversight, promotion activities towards third parties lead to over – or inaccurate prescription or recommendations, and, in some cases, where incentives are profit-based.

- Excessive sales targets and inadequate oversight can lead to predatory sales behavior. In the retail banking industry, this has included:

- Unauthorized transactions on client accounts;

- Sale of insurance products to clients who do not meet eligibility requirements (and therefore cannot take advantage of them);

- Targeting the elderly or people conversing in their second language;

- Sale of loans to people who cannot meet repayment obligations. (Privacy and Information rights; Economic security rights; Right to an adequate standard of living; Right to housing).

- Heightened risks arise where salespeople are required to use discretion in evaluating customer fitness for access to a product and/or have the ability to access/ modify private customer information without adequate oversight.

- Influencing third parties leading to excessive or inappropriate prescription or recommendation of products: Where incentive structures influence a professional’s exercise of discretion, people may be given advice or products that are not appropriate for their personal circumstances, affecting their health and/or finances:

- Provision of baby formula to mothers in poverty by hospitals/ doctors receiving samples from companies, with subsequent impact on child health as mothers abandoned breastfeeding but could not afford an adequate amount of formula (see OHCHR) (Right to life; Right to health);

- Sale of “sub-prime” loans by mortgage brokers receiving commissions from lenders, at interest rates above market and/or to borrowers who could not afford repayments (see CESR) (Right to an adequate standard of living, including Right to Housing); and

- Over-prescription of potentially addictive painkillers facilitating or leading to addiction (Right to life; right to health).

- In the context of essential medicines, sales incentives that reward based on profits on products (rather than revenue) can drive up the price of essential medicines, reducing access to medicines for vulnerable persons (Right to life; Right to health).

Risks to the Business

- Reputational, Financial and Business Opportunity Risks: Scrutiny from governments, investors and civil society is becoming increasingly sophisticated and granular, including to the level of the existence and effect of sales targets. One example is the well-known Access to Medicine Index for the pharmaceutical industry, which includes Market Influence within its measurement areas, including “sales-based performance incentives and bonuses for sales agents.” Consequently, companies are unable to claim ignorance of expectations and best practices; to do so risks loss of investment, reputational risks and loss of access to business partners applying such standards in their criteria for engagement.

- Regulatory Risks: The impacts flowing from excessive sales targets and inadequate oversight can affect the reputation of an entire industry and potentially lead to increased regulation. The Banking Royal Commission in Australia was established in 2017 to inquire into and report on misconduct in the banking, superannuation and financial services industry, including fraudulent lending to elderly customers and the widespread provision of inappropriate and predatory financial planning advice. It was reported in 2020 that “about 40 pieces of … legislation sit on [the government’s] parliamentary agenda.”

- Reputational, Financial, Business Continuity, Regulatory and Legal Risks: As the impacts associated with this red flag tend to accumulate over time and exacerbate exiting social vulnerabilities, when impacts reach public consciousness, they tend to do so explosively, in the form of scandals, exposés and the partial collapse of industries. Companies face resulting litigation, increased scrutiny and regulation and reputational damage. For example, in the context of aggressive sales tactics and over-prescription in the opioid crisis, drug companies faced lawsuits, saw their reputation damaged and stock lose value. Reportedly 70% of Americans support “making drug companies pay the cost of addiction treatment services and cover the cost of naloxone, used to revive people who’ve overdosed.”

What the UN guiding principles say

*For an explanation of how companies can be involved in human rights impacts, and their related responsibilities, see here.

The UNGPs note that companies should “strive for coherence between their responsibility to respect human rights and policies and procedures that govern their wider business activities and relationships. This should include, for example, policies and procedures that set financial or other performance incentives for personnel…”. (Principle 16, Commentary).

- Where salespeople undertake predatory or unethical behavior on behalf of the company, the company may cause any human rights impacts suffered by customers as a result.

- Where companies offer certain kinds of incentives in higher risk contexts, they risk contributing to impacts, e.g. if a pharmaceutical company operating in countries where access to medicine is a salient risk does not take steps to decouple incentive schemes from the cost of essential medicines.

- Companies that offer incentives to third parties in order to sway their advice to customers/patients may contribute to impacts suffered by those that receive inappropriate advice or products.

Possible contributions to the SDGs

Addressing risks to people associated with this red flag indicator can contribute to, inter alia:

SDG 1: No Poverty, in particular Target 1.4: By 2030, ensure that all men and women, in particular the poor and the vulnerable, have equal rights to economic resources, as well as access to basic services, ownership and control over land and other forms of property, inheritance, natural resources, appropriate new technology and financial services, including microfinance.

SDG 3: Good Health and Well-Being, in particular Target 3.5: Strengthen the prevention and treatment of substance abuse, including narcotic drug abuse and harmful use of alcohol. Target 3.8: Achieve universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health-care services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all.

SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth, in particular Target 8.10: Strengthen the capacity of domestic financial institutions to encourage and expand access to banking, insurance and financial services for all.

Taking Action

Due diligence Lines of Inquiry

Promotional practices influencing third parties

- Do we have a policy in our marketing practices with regard to potential human rights impacts, and do we include our marketing practices as part of our human rights due diligence?

- What evidence do we have as to whether our salespeople are acting in practice in line with our marketing policies and prescribed processes?

- What are the different contexts in which our products/services will be sold/recommended to individuals? How might poverty, a lack of information or other vulnerabilities affect potential impacts from our products? What strategies do we have in place to ensure that our products are not sold/recommended in circumstances where the products might lead to harm to our customers?

- Do we provide adequate training to our sales professionals to enable them to make decisions guided by our human rights responsibilities?

- How might our salespeople, or the professionals they influence, be incentivized to act otherwise than in accordance with our policies?

- Do we have sufficient oversight over our salespeoples’ activities? How do we internally/ externally audit our practices?

- What grievance mechanisms do we have, who can access them and how do we act on results?

Sales targets and predatory sales behavior

- Who are our most vulnerable potential customers? How can our products/ services potentially be connected to negative impacts on people?

- Do our salespeople exercise discretion in evaluating the appropriateness of a product for customer? How is this guided or constrained?

- How can we track any increases in sales to potentially vulnerable people?

- In practice, how do our salespeople experience the relative pressures to both deliver on sales targets and protect vulnerable people from potential impacts associated with our products/services? Do they find the two to be in tension and do they know how to address those tensions in practice?

- Do our salespeople have the ability to access/modify private customer information? What protections/ oversight is in place?

Profit-based incentives and access to medicine

- How do we incentivize our sales teams across geographies in which we operate? Do our incentive structures reward for profits on products (as opposed to revenue)?

- Could our incentives structures be playing a role in high/ rising drug prices?

- If so, do we whether higher prices could exacerbate existing vulnerabilities among potential consumers and limit access to essential medicines?

- Can we find a way to decouple sales agents’ incentives from sales targets?

Sales incentives and over-prescription in pharmaceuticals

- Do we offer sales bonuses based on sales volume in the context of drugs prone to over-prescription?

- Could we avoid deploying sales agents for such medicines, or decouple sales bonuses from volumes?

Mitigation Examples

*Mitigation examples are current or historical examples for reference, but do not offer insight into their relative maturity or effectiveness.

Removing sales-based incentives:

- According to the 2018 Access to Medicines Index, GSK’s sales agents’ rewards are not solely based on sales targets. Instead, it “rewards other qualities such as technical knowledge and quality of service” (p.134). Novartis also “rewards other aspects such as performance, innovation, collaboration, courage and integrity” (p.138).

- In order to “help our customers out rather than catch them out with unexpected charges, short-term offers and products they do not need,” Natwest and Royal Bank of Scotland “remove[d] sales-based incentives from customer-facing employees in Personal and Business Banking, ensuring that staff are completely focused on meeting the needs of customers rather than selling products.” To mitigate the impact on salespeople, the banks “gave every eligible employee an increase to their guaranteed pay.”

- To address over prescription, pharmaceutical companies Cipla and Shionogi have “minimised the incentive to oversell by decoupling their sales agents’ financial rewards from the volume of antibacterial and antifungal medicines they sell.”

Alternative Models

Avoiding sales agents altogether: Johnson & Johnson, Otsuka and Teva do not deploy sales agents for at least some antibacterial and antifungal medicines.

Other tools and Resources

- Sales Incentives and Over Prescription: The Access to Medicine Foundation’s Antimicrobial resistance benchmark “evaluates how 30 pharmaceutical companies are responding to the global threat of antimicrobial resistance” including their sales promotion practices.

- Profit-based Incentives and Access to Medicine: Information on pharmaceutical companies’ performance on “Market Influence,” including sales incentives, can be found in the Access to Medicine Index.

- Financial Services Misconduct: e.g., Submission of Dr. Kym Sheehan and Prof. David Kinley of Sydney Law School to the Australian Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking and Financial Services Sector.

- Misleading marketing practices of infant formula in developing countries: OHCHR (2015) Breastfeeding a matter of human rights, say UN experts, urging action on formula milk.

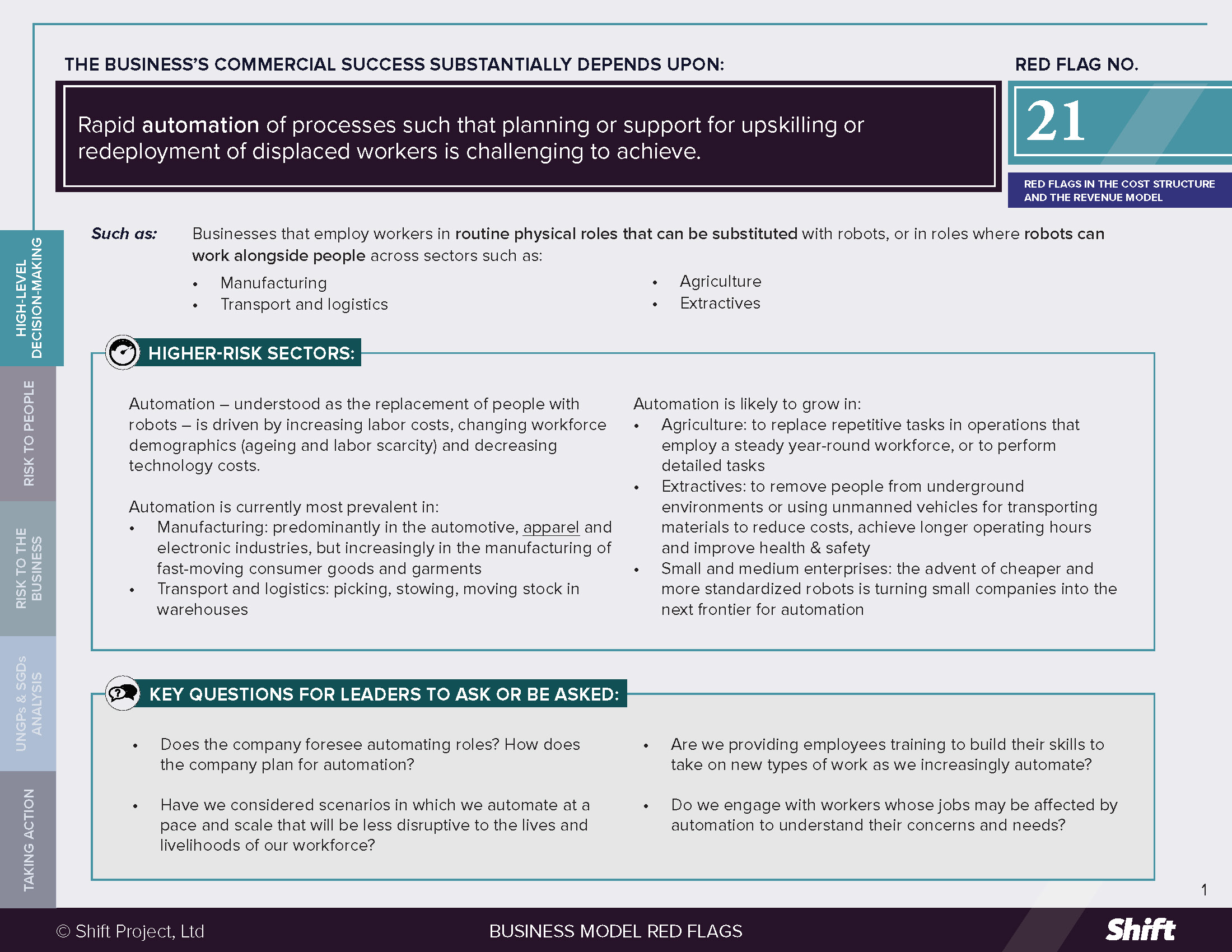

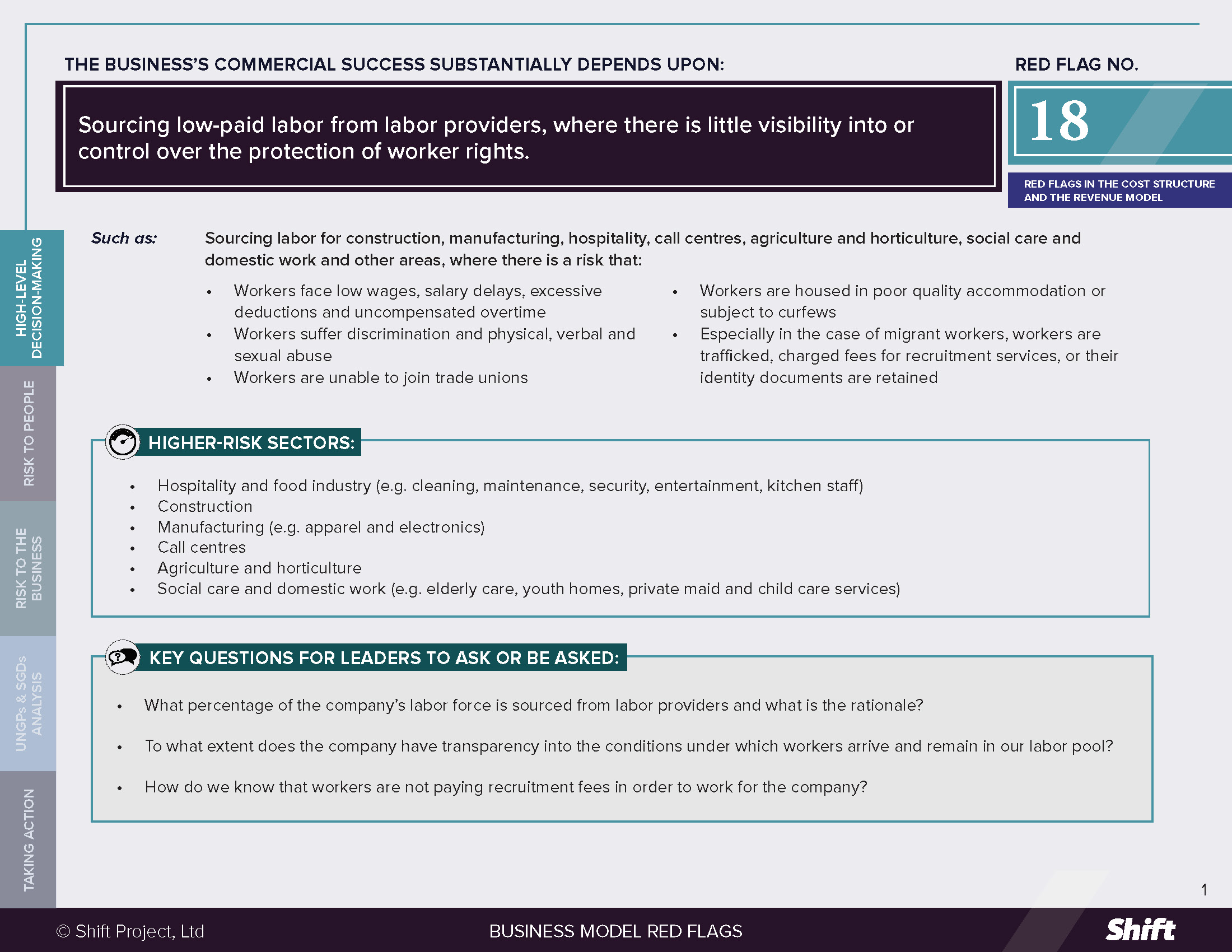

Red Flag 21. Automation at speed or scale that leaves workers little chance to adapt

RED FLAG # 21

Rapid automation of processes such that planning or support for upskilling or redeployment of displaced workers is challenging to achieve.

For Example

Businesses that employ workers in routine physical roles that can be substituted with robots, or in roles where robots can work alongside people across sectors such as:

- Manufacturing

- Transport and logistics

- Agriculture

- Extractives

Higher-Risk Sectors

Automation – understood as the replacement of people with robots – is driven by increasing labor costs, changing workforce demographics (ageing and labor scarcity) and decreasing technology costs.

Automation is currently most prevalent in:

- Manufacturing: predominantly in the automotive, apparel and electronic industries, but increasingly in the manufacturing of fast-moving consumer goods and garments

- Transport and logistics: picking, stowing, moving stock in warehouses

Automation is likely to grow in:

- Agriculture: to replace repetitive tasks in operations that employ a steady year-round workforce, or to perform detailed tasks

- Extractives: to remove people from underground environments or using unmanned vehicles for transporting materials to reduce costs, achieve longer operating hours and improve health & safety

- Small and medium enterprises: the advent of cheaper and more standardized robots is turning small companies into the next frontier for automation

Questions for Leaders

- Does the company foresee automating roles? How does the company plan for automation?

- Have we considered scenarios in which we automate at a pace and scale that will be less disruptive to the lives and livelihoods of our workforce?

- Are we providing employees training to build their skills to take on new types of work as we increasingly automate?

- Do we engage with workers whose jobs may be affected by automation to understand their concerns and needs?

How to use this resource. ( Click on the “+” sign to expand each section. You can use the side menu to return to the full list of red flags, download this Red Flag as a PDF or share this resource. )

Understanding Risks and Opportunities

Risks to People

The replacement of people with robots is estimated to displace 400 million workers and automate 15% of worked hours across all sectors between 2016 and 2030. While very few jobs are fully replaceable with robots, research shows that many jobs have a significant percentage of automatable activities. Automation’s greatest impact is forecast to be on jobs that consist of routine activities in predictable environments.

Automation of processes through robots can have a number of positive impacts.

In the short term, it can:

- Remove unsafe jobs: in mining, robots can help remove people from dangerous underground jobs, for instance, in Resolute’s Syama mine in Mali.

- Help people with restricted physical ability work.

- Make jobs more accessible for local workers: in mining, robots can provide a simpler visual interface which makes it easier for companies to train local workers, rather than rely on highly- skilled workers from outside the area.

- Increase the number of jobs: in fulfilment centers, robots can increase throughput thus enabling the center to hire more workers to deliver more orders.

- Help manage labor shortages: for example, labor shortages exacerbated by Covid-19 are incentivizing investment in agricultural robots.

In the long term, the history of labor market shifts shows that the overall effects of roboticization can be positive, as the new jobs created outpace the jobs lost and create greater economic prosperity. McKinsey estimates that automation could create between 555 and 980 million jobs by 2030, primarily by virtue of raising incomes through higher productivity, higher wages and lower consumer costs.

At the same time, McKinsey estimates that by 2030, 400 million workers will be displaced by automation and 75 million will need to change occupational category. This shift will put enormous pressure on workers around the world.

Automation will more negatively affect people who are already vulnerable: low paid and precarious workers and minorities that are over-represented in automatable jobs or under-represented in sectors that are likely to experience job growth. For example:

- In the US, African American and Latino workers are projected to be disproportionately affected by automation because they are over-represented in sectors such as transportation, food service and office clerks.

- In Bangladesh, automation in the ready-made garment (RMG) industry is forecast to disproportionately affect women, who comprise 80% of the workforce in the sector.

The negative impacts of automation on people are a result of the way in which companies introduce and use robots. The common denominator in cases of roboticization going wrong (where workers are dehumanized and seen as another input or cost in the production process) is lack of empathy: the ability to put oneself in someone else’s shoes.

When companies introduce automation without empathy with workers, the risks to people can be:

- Loss of Livelihood: Workers who lose their job because they are unable to relocate, retrain or redeploy. IMF research shows women and young workers aged 16-19 will be more negatively affected.

- Lower Wages: Research shows that displaced workers in the US earn 30% less in their next job, and that technology which replaces workers without increasing productivity tends to depress wages of low-skilled workers.

- Deterioration of Working Conditions: Workers in warehouses where robot use has increased, have complained of a faster pace of work and limited time to think. This can lead to an increase in accidents and have negative mental health impacts on workers caused by the pressure to work faster.

- Workplace Accidents: An investigation of health & safety records of warehouses that introduced robots showed a significant increase in workplace accidents.

- Mental Health Problems: Research of economic contractors shows that adverse economic transitions (job loss, transition to inadequate employment or reliance on social safety net) increases the prevalence of depression, suicide and substance abuse.

Risks to the Business

- Operational Disruption and Reputation Risk due to Worker Concerns and Insecurity: Where companies make decisions to automate – and this is done in ways that leave workers uncertain or insecure about their livelihoods – those companies can face public protests, union action, strikes and calls for boycotts. Examples of this include: Australian retailer Coles announcing the automation of warehouses (2020); Automation in Las Vegas casinos (2018) and automation at a Vancouver port (2019).

- Potential Loss of Social License and “Local Content” Incentives: In cases where governments have offered incentives for businesses, in particular, in the extractive industry, to set up operations and employ local people, it may be that large-scale layoffs due to rapid automation will undermine the support of the local government and the population. This possibility is already being raised and explored by civil society and research organizations.

What the UN guiding principles say

*For an explanation of how companies can be involved in human rights impacts, and their related responsibilities, see here.

A company may contribute to negative human rights impacts when it lays off workers as a result of rapid automation without first trying to offer re skilling or upskilling opportunities.

For example, in contexts where there is a weak social safety net or where workers lack alternative employment options or sources of income, rapid automation can result in job losses that leave workers without ways to secure an adequate standard of living. Compounded by the socio-economic context, this can negatively affect workers’ right to health, adequate housing and nutrition.

Buyers and investors may also contribute to negative human rights impacts if they require, respectively, their suppliers or investee companies to automate with no time to support workers in contexts where there are weak social safety nets.

Possible contributions to the SDGs

Technological progress is crucial to the fulfillment of the SDGs. However, to be true to the purpose of the SDGs, the use of technology needs to be underpinned by an understanding of how the loss of jobs due to automation can affect people’s basic dignity and rights.

The introduction of robots with empathy and with support for workers to re-train or upskill can help companies fulfill the following SDGs:

SDG 9: Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization and foster innovation, in particular Target 9.2: Promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization.

SDG 8: Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all, in particular Target 8.5: Achieve full and productive employment and decent work for all women and men, including for young people and persons with disabilities.

Taking Action

Due Diligence Lines of Inquiry

While the scale of automation’s impacts on people is undeniable, the nature and gravity of those impacts will depend on the way in which companies apply technology. This includes the due diligence companies carry out to identify and address negative impacts on people. Important questions to consider are:

- Does the company have a culture of empathy that looks not just at the benefits but also the human impacts of automation?

- Do we seek to understand what workers expect from their jobs in terms of progression and development?

- Do we ask how workers feel about the technology that surrounds them at work?

- Do workers have alternative employment options? (Are we the only significant employer in the local area?)

- How robust is the social safety net for workers who are displaced from their jobs?

- Does the business have in place processes to minimize the harm to workers of introducing and using robots?

- Do we have a process to assess impacts on people of new technology or automation in our operations?

- Do we look for unintended negative consequences from technology meant to make work “faster and easier”?

- Do we provide workers with opportunities for continuous learning? Do we recognize and reward that learning?

- Are our governance and internal processes and controls able to manage the additional complexity that comes with automation and technology?

- How do we engage with other stakeholders – including governments and trade unions – to identify ways to prepare workers for a changing landscape of work?

Mitigation Examples

*Mitigation examples are current or historical examples for reference, but do not offer insight into their relative maturity or effectiveness.

Mitigation examples fall into four categories:

- Engaging with Workers: Giving workers early notice that their jobs will be affected and engaging with them to understand their needs and expectations. Examples are:

- Research and forecasting: The European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training provides skills forecasts showing changes in the labor force and types of job openings, which enable workers, employers and governments to prepare in advance.

- Long-term talent pipelines: Caterpillar instituted a talent pipeline management system which enables the company to assess the volume of candidates for six core positions with a 10 year horizon, facilitating the creation of development plans to help workers progress their careers.

- A UK retailer engages with the trade union to set targets for pickers in their highly automated grocery home delivery fulfilment center.

- Supporting Redeployment or Relocation of Existing Workers: Companies can redeploy workers through upskilling or retraining. 62% of executives recently surveyed believed they would need to upskill more than a quarter of their workforce before 2023. Examples are:

- Large companies such as Orange, Verizon and Amazon have announced programs to retrain workers to help them move from positions vulnerable to automation to other jobs.

- Pilot projects in Bangladesh to increase workers’ digital literacy and use of computer-based design to adapt to the increased use of automation in garment factories, at the same time addressing gender imbalances by focusing the training on women.

- Support for workers to relocate to other places where they can access jobs: research in the US shows that the percentage of workers that relocate to access jobs has decreased since 1985; however, more than two-fifths of workers surveyed said they would be willing to relocate for work. Helping workers and their families consider and navigate the relocation process is therefore an alternative to bridging the skills gap.

- Supporting Future Workers to Access the Labor Market: OECD have seen a continued decrease in public spending on labor force training as a percentage of GDP since 1992. Examples of companies helping future workers develop skills abound, including:

- Collaborating to help unemployed youth enter the labor market: in the UK, Movement to Work works with employers to help them implement programs to tackle youth unemployment.

- Implementing employer-led skills development programs with credentials and certifications that workers can take with them as they move jobs.

- Supporting and providing vocational training. For example, JPMorgan Chase funds vocational training in the US through a variety of programs and partnership.

- Using Leverage to Advocate for Public Policies: e.g. wage insurance, universal basic income, smart taxation, closing the gender gap in STEM degrees (only 27% are women).

- Businesses can use their leverage to signal to governments changes needed in education curricula: for example, the Confederation of British Industry has commissioned research to better understand the curriculum changes needed to prepare young people to access the labor market.

- The Social and Economic Council of the Netherlands is a multi-stakeholder body composed of trade unions and employers’ organizations which makes recommendations to the government on how to mitigate the negative impacts of robotization in the labor market. This type of dialogue can help governments drive education and social policy to better prepare future workers and to prevent the dislocation associated with an increase in automation.

- France, Italy and Singapore have created personal training accounts, which allow workers to accrue credit which they can use towards training and upskilling and is transferable between employers. This provides workers with training opportunities that are not tied to their current employer.

- Countries are also creating “skills ecosystems” that enable workers to chart their career path and access lifelong learning, such as Singapore’s Skills Future Movement.

Alternative Models

Alternative models are examples of companies that retain workers instead of replacing them with robots. This does not mean the companies are not automating. It means they are integrating robots with their existing workforce in ways that benefit both workers and the business.

- One emerging trend is to have robots and workers collaborating side-by-side. Research in the automotive sector shows that assembly lines where workers and robots (“co-bots”) worked together were more efficient than lines where workers or robots worked alone.

- Another trend is using automation as an opportunity to provide workers with new skills, particularly to workers who are generally disempowered such as women or ethnic minorities.

Other tools and resources

General:

- OECD (2019) OECD Employment Outlook 2019: The Future of Work.

- International Labour Office (2019) Work for a brighter future: Global Commission on the Future of Work.

Sector specific Examples:

- ILO, David Kucera and Fernanda Bárcia de Mattos (2020) Automation, employment and reshoring: Case studies of the apparel and electronics industries: a study of automation in the apparel and electronics industries.

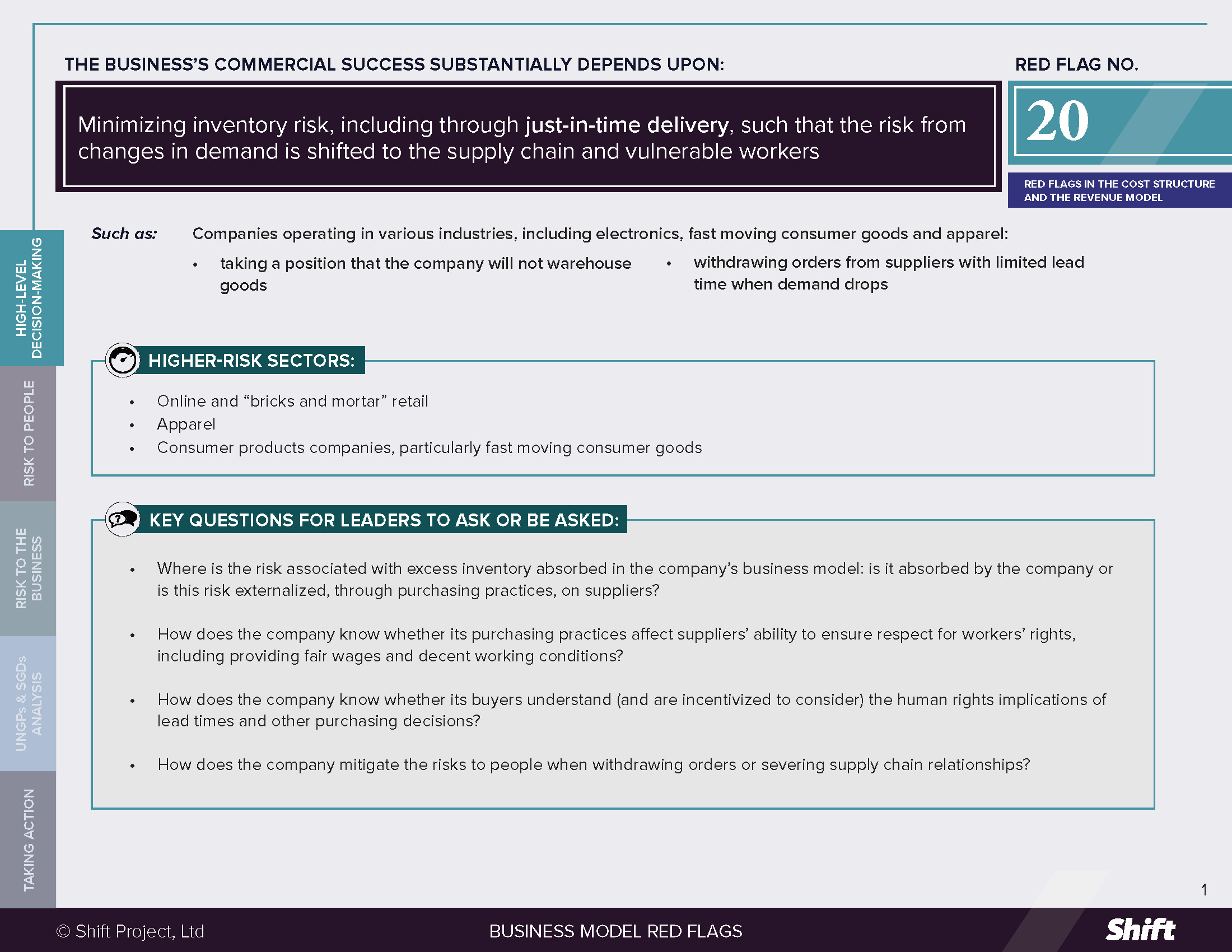

Red Flag 20. Shifting inventory risk to suppliers with knock-on effects to workers

RED FLAG # 20

Minimizing inventory risk, including through just-in-time delivery, such that the risk from changes in demand is shifted to the supply chain and vulnerable workers.

For Example

Companies operating in various industries, including electronics, fast moving consumer goods and apparel:

- taking a position that the company will not warehouse goods

- withdrawing orders from suppliers with limited lead time when demand drops

Higher-Risk Sectors

- Online and “bricks and mortar” retail

- Apparel

- Consumer products companies, particularly fast moving consumer goods

Questions for Leaders

- Where is the risk associated with excess inventory absorbed in the company’s business model: is it absorbed by the company or is this risk externalized, through purchasing practices, on suppliers?

- How does the company know whether its purchasing practices affect suppliers’ ability to ensure respect for workers’ rights, including providing fair wages and decent working conditions?

- How does the company know whether its buyers understand (and are incentivized to consider) the human rights implications of lead times and other purchasing decisions?

- How does the company mitigate the risks to people when withdrawing orders or severing supply chain relationships?

How to use this resource. ( Click on the “+” sign to expand each section. You can use the side menu to return to the full list of red flags, download this Red Flag as a PDF or share this resource. )

Understanding Risks and Opportunities

Risks to People

- Some business models support commercial viability by externalizing the risks associated with changing levels of consumer demand on suppliers, rather than absorbing it in the business model.

- Companies may do this by way of:

- Making last minute demands, changes or cancellation of orders;

- Using contracts by which the supplier assumes the cost and risk of the product until delivered;

- Avoiding warehousing goods by utilizing a “just in time” inventory/sourcing model.

- As a result:

- When demand spikes, and the purchasing company places large volume orders with short lead times, suppliers may see no alternative but to demand excessive overtime. (Right to just and favorable conditions of work; Right to a family life; Right to Health).

- A joint ETI/ILO survey on purchasing practices in 2017, to which responses were received from over 1,400 suppliers in 87 countries, found that only 17% of suppliers surveyed considered their orders to have enough lead time.

- When demand drops, the purchasing company may cancel orders on short notice and/or refuse to take responsibility for goods that have already been produced. IndustriALL has noted that such cancellations leave factories holding the goods, unable to sell them to the customer that ordered them, and in many cases unable to pay the wages of the workers who made them.

- When demand spikes, and the purchasing company places large volume orders with short lead times, suppliers may see no alternative but to demand excessive overtime. (Right to just and favorable conditions of work; Right to a family life; Right to Health).

- Purchasing practices such as this may, without appropriate mitigation measures, place heavy pressure on suppliers working on narrow margins. Risk and its associated costs are pushed up the supply chain and absorbed by the most vulnerable people – such as factory workers, including migrant workers, women workers, producers and small-holder farmers – affecting their livelihoods and those of their families. Suppliers under excessive pressure may not pay wages or overtime, or not provide safe working conditions; they may pregnancy test workers pursuant to a view that pregnant workers are not financially viable. Risks are exacerbated when the purchasing company(ies) provide little or no commitment to long-term sourcing, disincentivizing investment in improving working conditions (Right to just and favorable conditions of work; Right to Health).

Risks to the Business

- Operational Risks:

- Purchasing practices that situate inventory risk with suppliers can leave suppliers with cash flow challenges and unpredictability that disincentivizes them from investing in compliance with codes of conduct. Such practices can also cause suppliers to outsource (including illegally) to subcontractors, increasing the complexity of the supply chain and reducing visibility and control on the part of the buying company.

- Where the company does not keep an inventory of its products and relies on a small number of suppliers, it can be vulnerable to inventory shortages: in 2019, German-based Adidas’s sales growth declined due to “supply chain shortages” when “the company’s suppliers—nearly all of whom are based outside Germany—did not keep up with customer demand.”

- The Covid-19 situation in 2020 further demonstrated the risks to the company of relying on, inter alia, just in time models and the detrimental impact of this practice on supply chain resilience.

- Reputational and Financial Risks:

- Companies with purchasing practices that lag behind leading practices may receive poor results in the Better Buying review, a growing online platform that allows suppliers to anonymously rank the buying practices of brands and retailers.

- During the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic, companies leaving overseas suppliers with excess inventory received negative publicity, including through Workers’ Rights Consortium’s “Brand Tracker” which listed apparel labels and retailers that were and were not paying their suppliers for orders in production or completed. From an investment perspective, research on the link between public sentiment on corporate responses to the pandemic and financial flows found that companies with labor and supply chain practices that were seen as taking action to secure their supply chain experienced higher institutional money flows and less negative returns.

What the UN guiding principles say

*For an explanation of how companies can be involved in human rights impacts, and their related responsibilities, see here.

The UNGPs note that companies should “strive for coherence between their responsibility to respect human rights and policies and procedures that govern their wider business activities and relationships [including] …. procurement practices.” (Principle 16, Commentary).

If a company engages in purchasing practices that place undue time and/or financial pressure on suppliers, incentivizing or facilitating them to cause human rights impacts on workers, they contribute to impacts.

Possible Contributions to the SDGs

Addressing risks to people associated with this red flag indicator can contribute to, inter alia:

SDG 10: Reducing inequalities within and between countries.

This goal becomes relevant as profit margins and returns are concentrated at the buyer/investor level, with less and less value making it into the pockets of the poorest in the supply chain.

SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth, in particular Target 8.8 on protecting “labor rights and promot[ing] safe and secure working environments for all workers, including migrant workers, in particular women migrants, and those in precarious employment.

SDG 1: End Poverty in All its Forms Everywhere, in particular Targets 1.1 and 1.2 on eradicating extreme poverty and reducing by half the number of people living in poverty (according to national definitions).

Taking Action

Due Diligence Lines of Inquiry

- Do we have sufficient budget allocated to warehousing products? If not, how are we ensuring that factories can produce in advance and keep overtime within acceptable limits?

- Do buyers have sufficient knowledge, incentives and support to assess how and when their decisions will place human rights at risk, and to know from whom to seek assistance when they do?

- How do we know whether our buyers follow our processes, rules or guidelines in practice when engaging or contracting with suppliers?

- Do we engage with our suppliers in ways that help us understand how far they can go to meet our demands while still respecting the rights of their workers? Do we work with suppliers in countries of production to increase worker protections?

- Do we take a short term, transactional approach to supply chains or do we develop supply chain partnerships? For example, do we see high turnover among suppliers?

Mitigation Examples

*Mitigation examples are current or historical examples for reference, but do not offer insight into their relative maturity or effectiveness.

- “Kellogg undertakes a ‘joint business planning process’ with its key suppliers that includes the evaluation of its responsible sourcing practices. Issues such as purchasing practices, ordering, lead-time expectations, production schedule changes, and complicated specifications for ingredients and sizes are discussed with suppliers and that responsible sourcing is also embedded in global sourcing events and category development. In addition, Kellogg discloses that procurement leadership and category managers are responsible for the execution of the Global Sustainability Commitments, including social accountability, which is reflected in their annual performance plans and annual incentives.” (Know the Chain).

- ACT (Action, Collaboration, Transformation) is an “agreement between global brands and retailers and trade unions to transform garment, textile and footwear industry and achieve living wages for workers through collective bargaining at industry level linked to purchasing practices.” In September 2019, ACT adopted a joint due diligence framework including Global Purchasing Practices Commitments, a Responsible Exit Policy and Check List and a Purchasing Practices Self-Assessment tool (covering64 different aspects of purchasing practices in 16 areas), including a commitment to “fair terms of payment” and “better planning and forecasting.” The ACT Accountability and Monitoring framework provides ACT member brands with an agreed set of indicators and monitoring instruments to implement their purchasing practices commitments.

- At a time of decreased sales during the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic, UK supermarket Morrisons committed to advancing payments to its smaller foodmakers, farmers and businesses that stock its shelves; H&M announced that it would take delivery of already produced garments, as well as goods in production, and that the goods would be paid for under previously agreed payment terms and prices; L’Oréal prioritized immediate payments to and shortening payment terms with suppliers who were at risk of going out of business; and Unilever offered early payment to its most vulnerable small and medium-sized suppliers to help them with financial liquidity. (See Triponel and Sherman (2020)). Primark created the Primark Wage Fund, Asia to help pay the wages of garment workers affected by Primark’s decision to cancel clothing orders.

Alternative Models

Spanish fashion company Alohas’ “business model revolve[s] around an on-demand production process.” The company previews upcoming designs to customers early in the season and makes them available at a discount rate. Once it calculates how many units of each new style should be produced it commences manufacturing. Alohas notes that “on-demand reverts the sales cycle by applying a discount for early purchases and offering the product at full price only once stock has been made available. Meaning we don’t adhere to the traditional sales calendar anymore.”

Other Tools and Resources

- ACT (Action, Collaboration, Transformation), including the ACT Global Purchasing Practices Commitments.

- ILO (2017) Purchasing practices and working conditions in global supply chains: Global Survey results: provides the results of an ILO/ETI global survey on purchasing practices and working conditions, to which over 1,400 suppliers from 87 countries responded, with the sample covering nearly 1.5 million workers.

- ETI (2017) Guide to Buying Responsibly: The guide includes best practice examples and outlines the five key business practices that influence wages and working conditions.

- Better Buying has created a tool for suppliers to anonymously rate their buyers against 7 purchasing practices, developed through consultation with suppliers. Buttle (2018) Can there be fair rules for the ‘purchasing practices’ game?: a ETI blog post from ETI’s Apparel and Textiles Lead summarizes standards for company purchasing practices and offers recommendations for improvements in practice.

- Workers’ Rights Consortium’s “Brand Tracker” lists apparel labels and retailers that were and were not paying their suppliers for orders in production or completed during the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic.

- A. Triponel and C Bader (2020) Coronavirus is shining the spotlight on unhealthy supply chains: cleaning them up will help both business resilience and worker wellbeing.

- A. Triponel and J. F. Sherman (2020) Moral bankruptcy during times of crisis: H&M just thought twice before triggering force majeure clauses with suppliers, and here’s why you should too.

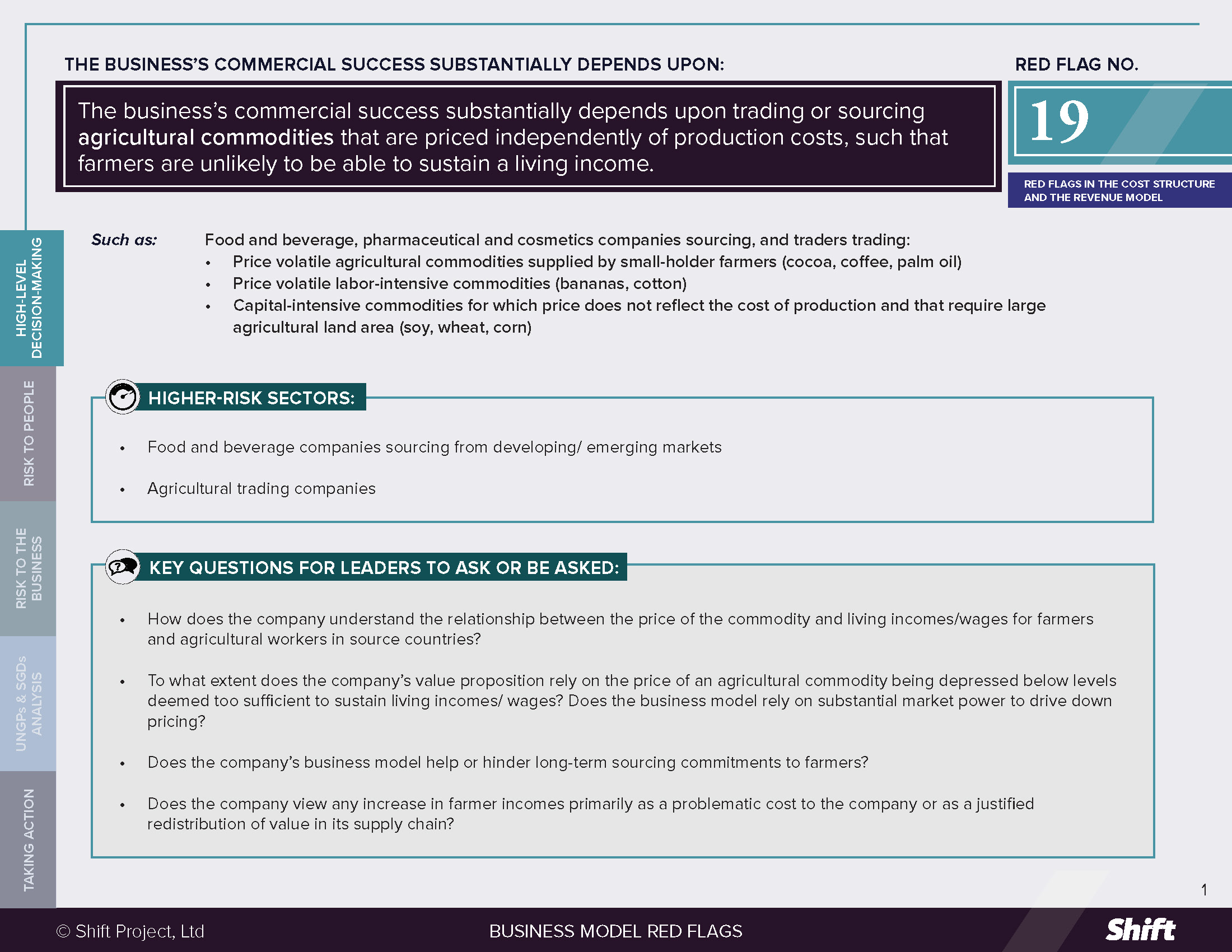

Red Flag 19. Sourcing commodities that are priced independent of farmer income

RED FLAG # 19

The business’s commercial success substantially depends upon trading or sourcing agricultural commodities that are priced independently of production costs, such that farmers are unlikely to be able to sustain a living income.

For Example

Food and beverage, pharmaceutical and cosmetics companies sourcing, and traders trading:

- Price volatile agricultural commodities supplied by small-holder farmers (cocoa, coffee, palm oil)

- Price volatile labor-intensive commodities (bananas, cotton)

- Capital-intensive commodities for which price does not reflect the cost of production and that require large agricultural land area (soy, wheat, corn)

Higher-Risk Sectors

- Food and beverage companies sourcing from developing/ emerging markets

- Agricultural trading companies

Questions for Leaders

- How does the company understand the relationship between the price of the commodity and living incomes/wages for farmers and agricultural workers in source countries?

- To what extent does the company’s value proposition rely on the price of an agricultural commodity being depressed below levels deemed too sufficient to sustain living incomes/ wages? Does the business model rely on substantial market power to drive down pricing?

- Does the company’s business model help or hinder long-term sourcing commitments to farmers?

- Does the company view any increase in farmer incomes primarily as a problematic cost to the company or as a justified redistribution of value in its supply chain?

How to use this resource. ( Click on the “+” sign to expand each section. You can use the side menu to return to the full list of red flags, download this Red Flag as a PDF or share this resource. )

Understanding Risks and Opportunities

Risks to People

- Of the estimated 500 million small-holder farmers worldwide, 200 million are producing food within global supply chains. Fifty percent of the world’s undernourished people are smallholders and their families.

- Farmers and smallholders have limited influence in negotiating terms of trade and receive an ever-diminishing share of the fruits of their labor.

- A range of structural barriers underlie this disadvantage, at the levels of the supply chain, commodity sector and public policy. ETI notes that business models intersect with these barriers in many ways, including:

- Consolidation of the market into a limited number of food retailers with substantial market power, that is often used to drive down prices and leave farmers unable to negotiate higher pricing.

- The effect of lowest cost or “discounter models” in the food retail sector, driving price competition and increased pressure on prices in the supply chain.

- Price squeezes on suppliers increase the risk of human and labor rights violations in food and farming supply chains, often affecting the most vulnerable in rural communities, including small-holder farmers, particularly women and migrant workers. The inability of a farmer to provide for his or her family leads to a considerable loss of dignity in some rural communities, increasing marginalization and compounding the risk of human rights impacts.

- With respect to some commodities, farmers and their families find themselves in a poverty trap: without funds or investment to grow high-quality produce or plan ahead, they face low prices and/or harvest early, reinforcing the poverty cycle. Farmers also face theft and are increasingly vulnerable to extreme weather events.

- Where lowest cost is the largest business driver, e.g. in the commodities market, farmers, fishermen and smallholders have limited influence in negotiating terms of trade and receive an ever-diminishing share of the fruits of their labor. [See also Red Flag 14]

- Poverty erodes or nullifies economic and social rights such as Right to health, adequate housing, food and safe water, and the Right to education (OHCHR).

Risks to The Business

Business Continuity Risks:

- Extreme price pressure on farmers can undermine availability of product and stability of supply in the near term and lead to an exodus from farming over time.

Reputational Risks:

- Undue price pressure on supply chains in certain geographies can lead to civil society exposés, resulting in damage and damage to reputation, brand and customer loyalty.

Business Opportunity:

- Focusing on improved livelihoods for people within the supply chain helps to bring them into the consumer base; failure to do so foregoes this opportunity.

What the UN guiding principles say

*For an explanation of how companies can be involved in human rights impacts, and their related responsibilities, see here.

The UNGPs note that companies should “strive for coherence between their responsibility to respect human rights and policies and procedures that govern their wider business activities and relationships [including] ….procurement practices.” (Principle 16, Commentary)

- Companies sourcing commodities through their supply chain from farmers who receive less than a living income may be directly linked to impacts on the adequacy of the farmers’ standard of living.

- If a company’s purchasing practices push costs upstream in the supply chain – whether alone or as part of an industry-wide behavior – in ways that prevent farmers from achieving a living income, they contribute to the impacts experienced by farmers.

Possible Contributions to the SDGs

Addressing impacts on people associated with this red flag indicator can contribute to, inter alia:

SDG 1: Eradication of poverty in all its forms.

SDG 10: Reduce inequality within and among countries.

Oxfam has noted that, “perpetually low income levels are one of the key reasons why farmers remain stuck in poverty… For many small- scale farmers, significant 2 exist between their actual income and income levels sufficient to ensure a decent standard of living…”. Oxfam cites structural barriers, including at the level of individual supply chains, which reinforce the “significant imbalance between the risks of agriculture shouldered by farmers and their power to shape their own market participation.”

By addressing the impacts on living income from corporate sourcing practices and price influencing, companies can contribute to lifting the poorest people in agriculture into more sustainable livelihoods, and in turn help them to escape poverty and realize their rights, from better health to nutrition to education.

Taking Action

Due Diligence Lines of Inquiry

- Are our purchasing practices designed to drive down pricing, or do they have the effect of doing so? How do we know?

- Are the length of our supply chain commitments/ contracts helping or hindering our ability to use our leverage to secure better prices for farmers?

- Have we explored increasing dialogue with, or forming partnerships with, farmers in our supply chain? Have we sought to understand the real costs associated with production of the commodity, based on their experience?

- Are we engaging in multi-stakeholder initiatives (MSIs) aimed at addressing human rights impacts with respect to the commodity on which we rely? Where a relevant MSI doesn’t exist, can we learn from analogous efforts and explore opportunities to create one?

- Have we explored how to engage and educate our customers if they must absorb some price increase to protect farmer living standards?

- Are we prepared to experiment – and learn from failures or missteps – in tackling the difficult challenge of livelihoods in supply chains? Can we explore opportunities to promote and facilitate the growth of new forms of business in our supply chain that can channel more resources to farmers (e.g. cooperatives, women- owned enterprises, social enterprises)?

Mitigation Examples

*Mitigation examples are current or historical examples for reference, but do not offer insight into their relative maturity or effectiveness

- The Farmer Income Lab, launched by Mars, with Dalberg and Wageningen universities and Oxfam USA, is a collaborative effort to identify ways to increase smallholder farmers’ incomes – beginning with Mars’ supply chains in developing countries – and to understand how to create positive outcomes for farmers at scale.

- Companies participating in the voluntary Sustainable Vanilla Initiative commit to pre-competitive projects to improve quality, product traceability, good market governance and the livelihoods of smallholder farmers who form the foundation of the global vanilla bean trade.