This series captures the research findings from our analysis of 3073 social and governance indicators used in ESG data providers’ products or reporting requirements.[1] In our Guardrails, we focus first on the problems, spotlighting the types of indicators that offer minimal insight, or worse, incentivize poor practices. In our Guidelines, we then turn to indicators and metrics that are more robust, illuminating the pathway to better measurement. In our Thematic Deep Dives, we review ESG indicators related to specific issues (Occupational Health and Safety, Living Wage, Community-Focused Impacts). These deep dives identify pitfalls in indicator formulation as well as good practices that can inform better measurement of companies’ social performance on these topics.

Across the series, we will exemplify the good, bad and ugly of social indicators and metrics. Our goal is not to offer yet another set of competing indicators, but to share what we’ve learned about good indicator design in order to inform healthy debate, collaboration and innovation to improve the S in ESG.

This series is for everyone and anyone working to improve the ways in which we evaluate companies’ social performance.

Deep Dive Series

A series of deep dives evaluating better social indicators and metrics for occupational health and safety, living wage, and community-focused impacts.

3 resources

DEEP DIVE 01: Occupational Health and Safety Indicators

DEEP DIVE 02: Living Wage Indicators

DEEP DIVE 03: Community Focused Indicators

Guardrails and guidelines for indicator design

In climbing, guidelines are cords or ropes to aid passers over a difficult point or to permit retracing a course. Guardrails are physical barriers used to prevent people from falling from a height or from straying from a pathway or road into dangerous areas. So, both are put in place when the journey and terrain may be hard to navigate.

In the context of designing social indicators and metrics, we need both guardrails and guidelines, so we’ve structured our initial findings within the series around these.

If we fail to reclaim the measurement of companies’ social performance as a tool to advance business respect for human rights, the S in ESG will remain divorced from the investor and business decisions that determine whether business is done with respect for people’s dignity. We hope this series can play a part in sustaining, advancing and scaling practices that lead to better outcomes for workers, communities and the people impacted by the use of products and services.

Guardrails

A series of guardrails for designing better social indicators and metrics.

3 resources

Guardrail 01: Avoid indicators that create perverse behavioral consequences.

Guardrail 02: Avoid indicators that encourage unjustified conclusions.

Guardrail 03: Avoid indicators that offer insight into a company’s intentions but no insight into whether these are followed through in practice.

Guidelines

A series of guidelines for designing better social indicators and metrics.

6 resources

Introduction to Guideline 01: Use indicators that are strong predictors of business decision making and behavior.

Guideline 1: Use indicators that are strong predictors of business decision making and behavior.

A: Evaluating companies’ governance practices

Guideline 1: Use indicators that are strong predictors of business decision making and behavior.

B: Focus on Stakeholder Engagement indicators.

Guideline 1: Use indicators that are strong predictors of business decision making and behavior.

C: Focus on a company’s social targets.

Guideline 2: Use indicators that offer insight into the quality of a company’s due diligence.

Guideline 3: Use indicators that offer insight into a company’s contribution to positive outcomes for people.

Advancing the S in ESG

The field of sustainability and responsible business conduct is faced with a significant opportunity: to coalesce around a core set of select, standardized indicators and metrics that meaningfully measure companies’ social performance regardless of their industry sector. This is key to equipping investors, business leaders, regulators and civil society with the tools to push to scale business practices that are in line with the principle of basic dignity and equality for all.

Success will significantly contribute to tackling inequalities, ensuring business actions towards net zero and net positive have the social license to proceed at the urgent pace required, and adapting business models and global value chains so that they deliver resilience to businesses and the stakeholders they impact. Failure risks ushering in more, already well-catalogued business-related harms and risks to people, planet and prosperity, likely with evermore multi-generational consequences.

The good news is that most stakeholders have embraced the pressing need for convergence around corporate sustainability reporting standards, including the indicators and metrics against which companies should disclose information and that should be used to evaluate corporate performance. Even better, recent institutional coordination and collaboration has set the stage for well-governed and inclusive processes needed to achieve such convergence.

Barriers to strengthening the S in ESG

Any ambitious project has risks that need managing. The challenge of building consensus across diverse stakeholders around indicators and metrics that offer credible insight into a company’s social performance is no exception.

Some risks are the consequence of positive dynamics. For example, the welcome growing attention to the S in ESG has resulted in thousands of social indicators and metrics already being developed by mainstream data providers and more targeted ranking and rankings. But the risks is that in a bid to identify a smaller set of indicators, we select the most commonly used indicators, in spite of broad recognition that these may not be fit for purpose.

In addition, the urgent need to effect a step change in the scale and quality of corporate reporting and assessment on social issues also carries the risk that project timelines prevent us from interrogating the devil in the detail of indicator formulations, such as when indicators may have perverse, unintended consequences.

The consequence of such risks is more than inconvenience and frustration. We could end up with solutions that confuse decision-makers, reflect the lowest common denominator of thinking and practice, or fail to ward off critiques of blue-washing and corporate capture, but also of so-called woke capitalism.

[1] Shift was unable to verify whether the non-public indicators and metrics that we used for our analysis are the most up to date versions used by data providers at the time of writing (April 2024). We also recognize that the underlying methodologies used to reach a judgement on a company’s performance against an indicator may offer more nuance that we could not access for our research.

Business Model Red Flags

About the Red Flags

GENERAL OVERVIEW

Shift’s Business Model Red Flags is a set of indicators that may be found in dominant or emerging business models in and across a range of sectors. They are not intended to be an exhaustive list but may help spark reflection and enable the identification of additional red flags.

In September 2025, 13 of the 25 Red Flags were updated and expanded to integrate a climate lens. The revised tool now features 14 climate-linked Red Flags — 13 updated and one newly developed — each illustrated with real-world examples of corporate action and material consequences that have arisen where a business has failed to mitigate the risks inherent in its business model.

THE BUSINESS MODEL RED FLAGS ARE INTENDED FOR THE USE OF

- Business leaders seeking to identify and address risks to people that may be embedded in the business model, in order to ensure the resilience of value propositions and strategic decisions and build more integrated approaches to climate and human rights risks and impacts.

- Lenders and Investors scrutinizing their portfolios for human rights risk, including as it pertains to climate action, engaging with clients and investees and diagnosing whether significant human rights incidents are likely to be repeated by the company concerned, replicated in other parts of their portfolio or are being hard-wired into company climate strategies and transition plans.

- Regulators, analysts and civil society organizations seeking to strengthen their analysis and engagement with companies and investors on business model-related risks to people, including how they may be interacting with climate-related risks.

There are 25 Business Model Red Flags

(To see an overview chart with all 25 red flags, click here)

The Red Flags are organized around three features of a business model:

HOW EACH RED FLAG IS ORGANIZED

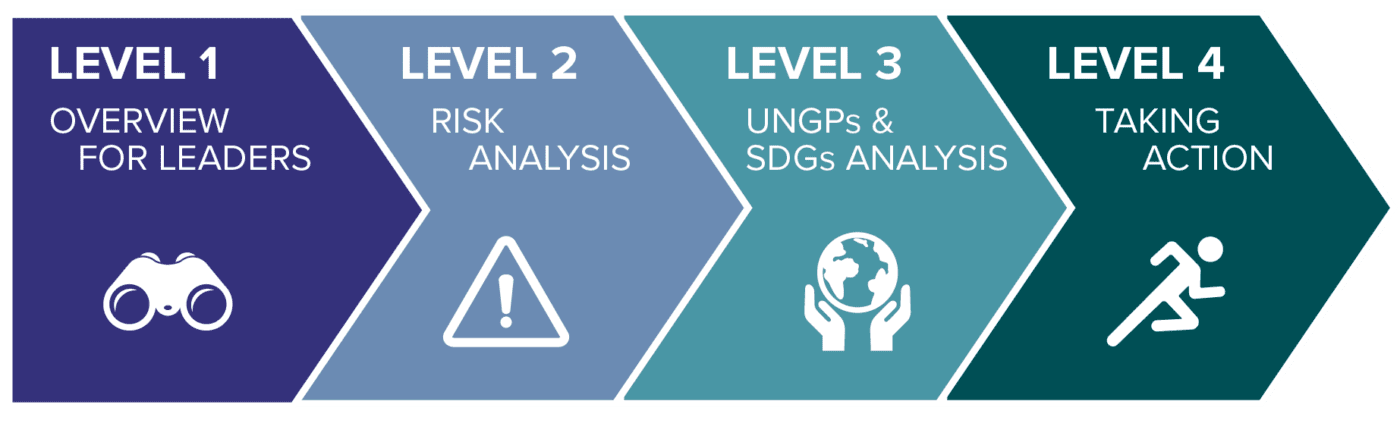

Each red flag is supported by a guidance document, organized into four levels:

Level One: Overview for Leaders

This includes:

- Higher risk sectors in which the red flag feature is most prevalent;

- Key questions for leaders to ask or be asked to aid decisions about whether further action is needed.

Level Two: Risk Analysis

This includes:

- Risks to People: the key human rights risks associated with this red flag, absent appropriate mitigation efforts;

- Risks to the business: evidence of legal, financial, operational and reputational risks that can arise as a result of companies not addressing the red flag.

Level Three: UNGPs and SDGs analysis

This sets out:

- What the UNGPs say, with particular reference to how companies might be involved with the adverse human rights impacts associated with the red flag;

- Possible contributions to the Sustainable Development Goals that can be achieved with effective mitigation or removal of the red flag;

Level Four: Resources for taking action

This includes:

- Due diligence lines of inquiry for deeper analysis of the company’s impact and how it could effectively mitigate the risks associated with the red flag;

- Mitigation examples illustrating how companies have in practice sought to reduce the impacts associated with the red flag;

- Alternative model examples of companies that have either designed or redesigned their business model to function without the risk elements highlighted in the red flag;

- Additional tools and resources to guide further analysis.

Examples of Investor Application of Red Flags

| Institution | DD Stage Referenced | Use | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| APG

Pension provider |

Risk Identification Portfolio Engagement |

“Additional conditions and mitigants are required for companies operating in high-risk areas. Moreover, in partnership with the Shift Project, we are developing our model of ‘red flags’ for companies in sectors exposed to high-risk business models, such as those handling sensitive data or having complex and vulnerable supply chains. This analysis is intended to bolster our human rights due diligence efforts and improve our engagement with companies on human rights.”6

FN 6: “…Shift’s Business Model Red Flags are key indicators present in dominant or emerging business models across various sectors. While not exhaustive, they serve to prompt reflection and aid in identifying additional red flags.” |

Catalyst for Change:Our approach to upholding respect for human rights (2024) |

| ABN AMRO

Bank |

Risk Identification | “In 2023 ABN AMRO developed a social risk identification tool (the Social Risk Heatmap), which provides a structured methodology to help us to identify human rights risks in our business environment. The Social Risk Heatmap shows potential impact in the sectors in which our clients operate. This may differ from the actual impact of our clients, which may be reduced through preventative measures taken to counter adverse human rights impacts. The risk level per sector is based on several indicators taken from the Impact Institute’s Global Impact Database and Shift’s Business Model Red Flags and focuses on four themes: labour rights, land-related rights, the right to life and health and the right to privacy and freedom of expression.” | Modern Slavery Statement (2024) |

| PGGM

Cooperative pension fund service provider |

Risk Assessment: Prioritization Portfolio Engagement | “To set our engagement targets, we have identified key outcomes and activity indicators that focus on tangible outcomes (e.g. number of child labour incidents remediated) for land and labor rights and on effective actions to reach those outcomes (e.g. evidence of improvements on purchasing practices and of robust human rights due diligence). This approach aims to look beyond policy commitment of a company and to focus on actual results and implementation quality. Although land and labour rights are already a subset of all human rights topics, they still cover a wide spectrum of issues. Therefore, a second level of prioritization is necessary in selecting engagement targets per company. For this, we consider multiple factors, including existing controversies, social benchmarks, and business model red flags.” | PGGM Human Rights: Proactive engagement on land and labour rights |

| Bridges Fund management Specialist sustainable and impact investment fund manager |

Risk Identification Risk Assessment Mitigation through Leverage | “We assess each potential investment against the SHIFT Business Model Red Flags framework to check whether there are human rights risks inherent in the business model. Where significant risks of potential harm are identified, we carry out further due diligence to understand those risks and assess whether they are manageable. If so, we work closely with management with the aim of ensuring that the potential negative impacts are mitigated and managed.” | Public Transparency Report for PRI (2023) |

| HUB24

Wealth and superannuation platform and technology provider |

Risk Identification Risk Assessment | “HUB24 takes a risk-based approach to identifying and assessing modern slavery risk in our operations and supply chain. Our modern slavery risk assessment considers the four key modern slavery risk factors of: [1] Vulnerable populations […] [2] High-risk geographies […] [3] High-risk sectors […] [4] High-risk business models: Business models that have higher human rights risks, including modern slavery risk. Examples include labour hire outsourcing with high use of precarious labour, low-cost goods and services, sourcing in countries with contested land use, and complex supply chains with limited visibility.”3Business Model Red Flags (FN3) |

Modern Slavery Statement (2023)

|

| Westpac

Bank |

Risk Identification | [Modern slavery] risks can arise due to the following factors: [1] Sector or Categories Risk […] [2] Country Risks […] [3] Vulnerable Groups […] [4] Business model risks: Business models that have higher human rights risk. Examples -Labour hire and outsourcing with high use of precarious labour -Franchising -Complex supply chains with limited visibility -Low-cost goods and services -Sourcing in countries with contested land use. |

Modern Slavery Statement (FY21) |

Menu of Red Flags

How to use this resource

There are 25 Business Model Red Flags. Each one is available to read online, by clicking on the word READ, or to download as a PDF. You can also use the search bar below to filter them by sector.

In September 2025, Shift updated the Red Flags to bring a climate lens to the dominant or emerging business models that are most likely to interact with climate change, and action to address it, to intensify and extend the range of human rights risks faced by workers and communities. These Red Flags are indicated by a ‘With Climate Lens’ icon.

Once you’ve picked the Red Flags you want to download, select them by clicking on the circled number of each Red Flag and choose ‘Download All Selected’. You may also choose to download the full series or to download a high level menu. For support, please contact communications [at] shiftproject [dot] org.

Red Flag 25. Greenhouse gas-intensive activities, products and services that contribute to negative impacts on people’s rights

RED FLAG # 25

Activities, products and/or services that significantly contribute to cumulative greenhouse gas emissions and the resulting physical climate change impacts that negatively affect people’s rights

FOR EXAMPLE

- The extraction, refining, distribution, sale and/or use of oil, tar sands, oil shale gas or natural gas

- The mining, processing, sale, and combustion of coal

- Companies that depend heavily on:

- Industrial land-use that results in extensive deforestation or other emissions-intensive land-use change (e.g., for palm-oil plantations or industrial livestock farming; see also Red Flags 12 & 13)

- Industrial processes that produce significant greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (e.g., steel and cement production, aluminum refining and smelting, fertilizer production)

- Intensive non-renewable fuel/energy use (e.g., technology data centers or large infrastructure in certain geographies, international shipping and aviation)

- Companies whose principal products depend heavily upon non-renewable fuel/energy use (e.g., automotive, shipbuilding and aerospace manufacturing, energy inefficient products)

HIGHER-RISK SECTORS

- Oil and gas exploration, extraction and transportation

- Coal mining, processing and transportation

- Fossil fuel-based power generation (e.g., lignite, coal, oil and natural gas)

- Carbon-intensive industrial sectors (e.g., petrochemicals, steel, iron, cement, aluminum and construction inputs)

- Industrial-scale conventional agriculture (e.g., industrial livestock farming, palm oil plantations, and other commercial farming activities)

- Forestry and forest products

- Large-scale transportation (e.g., industrial land transport, marine shipping, aviation)

- Transportation manufacturing (e.g., automotive, shipbuilding, aerospace)

- Large-scale infrastructure, including real estate

- Information and Communication Technology (see also Red Flag 21)

- Financial institutions that are significantly financing higher-risk industries that lack robust transition planning

Companies whose business models significantly depend on industrial activities, products or services such as these make important contributions to increasing global GHG concentrations and global temperature rise, which is increasing physical climate change

impacts (e.g., sea-level rise, ocean acidification, extreme weather), with severe and pervasive risks and harm for nature and for people, including to the human rights to life, health, food, water, and an adequate standard of living. Additional impacts on nature and people may also result from these industries linked to their depletion or pollution of natural resources (see Red Flag 13).

Questions for Leaders

- How is your business model compatible with the objectives of the Paris Agreement?

- How do you consider the impact of your climate action or inaction on people and how have you identified and engaged with potentially impacted workers (including value chain workers), communities, or consumers?

- To what extent have you integrated human rights considerations into your approach to managing your climate change impacts?

- Have you considered the regulatory, reputational, legal and financial risks associated with maintaining business as usual or taking insufficient action to address your climate impacts, including those risks that flow from the human consequences of your climate impacts?

- To what extent have you explored potential business opportunities in developing products or services that help achieve net zero in ways that respect and advance human rights?

How to use this resource. ( Click on the “+” sign to expand each section. You can use the side menu to return to the full list of red flags, download this Red Flag as a PDF or share this resource. )

Understanding Risks and Opportunities

Risks to People

|

Risk to the Business

-

Reputational risks: Individual company climate change impacts that affect human rights can generate considerable attention and multinational corporations are often targeted for criticism, particularly where people believe that appealing to governments may have little effect.

-

Even where legal action against a company relating to the human rights impacts of climate action or lack of action is unsuccessful, this can still present considerable reputational risk to the company.

-

Non-judicial proceedings can create reputational risks. Examples include communications by UN experts on the responsibilities of the financial backers of Saudi Aramco under the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, and a complaint with the American National Contact Point against insurance broker Marsh challenging the East African Crude Oil Pipeline planned by TotalEnergies in Uganda.

-

In 2022, the UN Commission on Human Rights (CHR) of the Philippines published its final report finding that the world’s biggest polluting companies can be held responsible for human rights violations and threats arising from climate impacts. CHR announced that the 47 investor-owned corporations, including Shell, ExxonMobil, Chevron, BP, Repsol, Sasol, and Total, could be found legally and morally liable for human rights harms to Filipinos resulting from climate change.

-

In 2025, the UK charity ActionAid publicly cut ties with HSBC, citing the bank’s continued financing of fossil fuel and industrial agriculture projects—amounting to over £153 billion between 2021 and 2023—as evidence the company is consistently “choosing profit over people and planet”. Civil society groups like BankTrack, Indigenous rights advocates, and major investor coalitions such as ShareAction have raised similar concerns about HSBC’s increasing financial, legal, and reputational risks tied to climate change.

-

-

Legal, financial and regulatory risks: Companies that do not take action to address their climate change impacts can face legal action for their contribution or preemptive legal action to avoid company activities that are perceived to negatively impact local communities or other stakeholders. Since 2016, there has been significant growth in climate change-related legislation. As of July 2025, 2967 climate change cases have been filed globally. Around 20% of climate cases filed in 2024 targeted companies, or their directors and officers. According to the London School of Economics’ Grantham Institute, which analyzes climate change litigation annually, “The range of targets of corporate strategic litigation continues to expand, including new cases against professional services firms for facilitated emissions, and the agricultural sector for climate disinformation”. While highly anticipated legal decisions have faced evidentiary hurdles, they have: (a) acknowledged the connection between GHG emissions, physical climate change and impacts on people, (b) scrutinized whether companies are taking reasonable and sufficient action to mitigate their impacts, and (c) explored the principle of companies being held liable for climate-related harm. Some notable legal developments include:

-

Litigants have had high profile successes in international courts and tribunals, including at the International Court of Justice and European Court of Human Rights, as well as advisory opinions form the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. The decisions and opinions emerging from these international bodies, which broadly affirm the right to a healthy environment, including a stable climate, provide important points of reference for litigation more broadly.

-

Royal Dutch Shell was taken to court in 2019 in the Netherlands on human rights grounds relating to the climate impact of its business. Although Shell won an appeal of the case brought by Milieudefensie in 2024, the court emphasised that companies, especially those that have contributed to climate change, have a responsibility and power to contribute to combating climate change. Further, the court affirmed in unequivocal terms that “protection from dangerous climate change is a human right” and these rights extend to what can be required of Shell.

-

A Peruvian farmer filed a lawsuit against German Energy giant RWE in German courts. His case argued that because RWE’s GHG emissions—estimated at 0.5% of historical global emissions—contributed significantly to glacial melting and heightened flood risk that impacted his property in Huaraz, Peru, RWE should compensate him for 0.5% of the costs of his flood protection investments. While the case was ultimately dismissed, after multiple appeals and years of litigation, for the first time, a court affirmed that large emitters could be held civilly liable under German law for climate damage—even across borders—based on scientific attribution and proportionate responsibility.

-

In September 2015, typhoon survivors and civil society groups in the Philippines, supported by Greenpeace and NGOs, filed a first‑of‑its‑kind petition with the Philippine Commission on Human Rights (PCHR), calling for a formal inquiry into whether 47 major corporate emitters (including Shell, ExxonMobil, Chevron, BP, Repsol, Sasol and Total) violated Filipinos’ rights by fueling climate change. The PCHR officially accepted the complaint in December 2015, held hearings from 2016 to 2018, and gathered extensive scientific data, testimonials, and expert briefs. In May 2022, the PCHR released its National Inquiry on Climate Change report, which concluded that the companies engaged in “wilful obfuscation” of climate science and that their actions were both morally and legally liable for human rights harms to Filipinos resulting from climate change.

-

In May 2024, Vermont became the first U.S. state to pass a “climate superfund” law aimed at holding major fossil fuel companies financially accountable for the costs of climate change. The law targets companies responsible for over one billion metric tons of GHG emissions and seeks to recover the state’s climate-related costs—including infrastructure damage, public health impacts, and other social harms—dating back to 1995. The move has inspired similar legislative efforts in states like New York, Maryland, and California. As of mid-2025, Vermont is still in the implementation phase, developing a damages assessment, while facing a legal challenge from the fossil fuel industry aiming to block the law before enforcement begins.

-

- Regulatory risks: Regulators globally are increasingly holding high-emitting companies accountable for both climate and human rights impacts. Governments are implementing carbon pricing mechanisms and stricter emissions standards, which increase operational costs for high emitting industries. Further, the EU’s Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive requires large firms to identify and mitigate adverse environmental and human rights impacts across their value chains and expects companies to transition their operations and value chains to a net zero economy in a rights-respecting way. (Note: As of publication, the existing text has been suspended pending a renewed legislative process that is expected to introduce some revisions.)

- Financial risks: Financial institutions are increasingly concerned about the longer-term, climate-linked financial stability of their portfolios, with investors increasingly favoring companies with robust climate strategies, potentially leading to reduced capital access for firms that fail to evolve their business models or do so at too slow a pace. Climate-related shareholder activism has increased dramatically in recent years.

- Business continuity risks: Companies that fail to address their contribution to climate change contribute to systemic risks with material, economy-wide implications for business continuity. For example:

- operational disruptions from extreme heat and declining worker productivity—estimated to fall 2–3% for every degree Celsius above 20°C, affecting billions of workers worldwide (e.g., in agricultural, construction, and manufacturing sectors).

-

critical process disruptions due to lack of raw materials (e.g., water-intensive manufacturing processes being halted by droughts)

-

supply chain disruptions from climate-related events, which could lead to up to $2.5 trillion in net losses by mid-century

What the UN Guiding Principles Say

|

In June 2023, the UN Working Group on the issue of human rights and transnational corporations and other business enterprises issued an information note on the UNGPs and climate change. In reference to the human rights instruments identified in UN Guiding Principle 12, the Commentary on Principle 12, the widely recognized right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment, and the understanding that anthropogenic GHG emissions are known to cause foreseeable and severe human rights impacts, the working group states that “States and business enterprises have obligations and responsibilities with respect to climate change, and with respect to the impacts of climate change on human rights.” According to the Working Group, “The obligations of States under the Guiding Principles to protect against human rights impacts arising from business activities includes the duty to protect against foreseeable impacts related to climate change.” With respect to business enterprises, the Working Group confirms that the responsibilities of those enterprises “under the Guiding Principles to respect human rights and not to cause, contribute to or be directly linked to human rights impacts arising from business activities, include the responsibility to act in regard to actual and potential impacts related to climate change.” As physical climate impacts are primarily the result of cumulative, global GHG emissions, it may be difficult to establish that any one company has caused a particular, location-specific climate-related harm (e.g., that one company’s GHG emissions in Australia are directly responsible for an extreme weather event in India). However, where a company makes a substantial contribution to cumulative GHG emissions, because their business model substantially relies upon them doing so, that company can be said to have contributed to climate harm, thus requiring the company to “take the necessary steps to cease or prevent its contribution and use its leverage to mitigate any remaining impact to the greatest extent possible”. This supports the expectation that companies with this business model feature should develop and implement robust, credible and Paris-aligned climate transition plans that respect the rights of workers and communities, as well as use their leverage toward achieving broader systemic transition. Corporations can also be linked to the human rights impacts associated with climate change through their business relationships. Examples of such linkage include a retailer sourcing from a supplier whose operations are carbon intensive, without any indication that the supplier will reduce them; or an investment fund holding equity in a fossil fuel company that has no discernible strategy to reduce its contributions to climate change. |

Possible contributions to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

Addressing impacts on people associated with this red flag can contribute to a range of SDGs depending on the impact concerned, but the most obvious and notable is:

-

SDG 13: Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts

Taking Action

Due Diligence Lines of Inquiry

-

Are we developing or have we published a robust, credible and science-based climate action strategy or transition plan that recognizes and addresses impacts on workers and communities arising from climate action?

-

How are we engaging our own workforce, our value chain workers, affected local communities and consumers/end-users in discussions about potential or actual action to address climate change impacts?

-

How are we evolving our governance, strategy, risk management and metrics/targets to ensure alignment with the objectives of the Paris agreement? How have we integrated potential impacts on people evolving from that evolution?

-

Recognizing both the consequences for the climate and for people’s human rights of GHG emissions:

-

Do we: undertake a robust analysis and disclosure of our contribution to global GHG emissions, including the following?

-

Identifying all our Scope 1, 2 and 3 GHG emissions throughout all our operations, with such identification being science-based, verifiable and informed by input from experts

-

Identifying hotspots across our operations and value chains

-

Disclosing climate-related information through recognized frameworks, such as GRI, CDP, TCFD, ESRS E1, or IFRS S2

-

-

Do we set ambitious, transparent and verifiable climate-related targets, including:

-

GHG emissions reduction targets across Scopes 1, 2 and 3 emissions

-

Transition-specific alignment targets that directly reflect our company’s progress on critical decarbonization milestones within our sector

-

-

-

Do we disclose the details of how our capital expenditure plan aligns with our climate action and human rights objectives?

-

Have we undertaken scenario analysis to assess resilience of the company’s operations and value chains, as well as the people its operations and value chains may impact, under various warming pathways (e.g., 1.5°C or 4°C)?

-

How do we ensure that our public affairs and policy advocacy activities are aligned with the objectives of our climate and human rights actions?

-

Do we rely on land-based carbon dioxide removals or the use of carbon credits to meet our GHG emissions reduction targets? If so, do we have mechanisms in place to evaluate the social and environmental integrity of doing so?

-

How do we assess whether our climate-related strategies and plans could impact stakeholder groups, namely, our own workers, workers in the value chain, communities and end users, with a particular focus on vulnerable populations?

Mitigation Examples

For companies whose business models substantially rely upon high emitting activities, products or services, examples of integrated, ambitious, organization-wide, and Paris-aligned action is not yet common. However, there are examples of companies that are making important, if partial, strides to address their contribution to climate impacts. For example:

Partial business model transition:

-

TransAlta is one of Canada’s largest electricity producers and is in the progress of changing its business model, undergoing a partial low carbon transition away from being a predominantly coal-fired power producer towards natural gas, renewables and energy storage. The company also played an active role in the provincial government’s measures to support workers and communities impacted by the transition.

-

Volvo Cars is attempting to transition its business model from producing vehicles dependent on fossil fuels to an electrified vehicle fleet. It originally targeted a fully electric vehicle offering by 2030, but the company updated its target in 2024 to 90–100% electrified sales by 2030. To address human rights-related risks in its value chain resulting from the transition to electric vehicles, particularly around critical minerals for components such as batteries, Volvo is exploring the use of different traceability techniques and “battery passports” that record the origins of raw materials, components, recycled content and carbon footprint of the battery.

Reconceptualizing climate-related target setting:

-

Large agrifood companies, such as Danone, Mars, Nestlé and PepsiCo, have acknowledged that, given the realities of the climate challenge within their sector, GHG emissions reduction targets are necessary but not sufficient. These companies have also set no-deforestation commitments for some or all high-risk commodities where deforestation is most prevalent. According to the 2025 Corporate Climate Responsibility Monitor, “these examples demonstrate how transition-specific alignment targets can complement emission reduction targets to guide sector-specific corporate transitions”.

Decision-useful climate disclosures that address the Just Transition:

-

Scottish and Southern Energy (SSE) in the UK has publicly disclosed its Just Transition strategy, which considers the impact its transition plan has on people.

-

In 2022, Enel was the first company to fully align its corporate climate disclosures with the Climate Action 100+ Net Zero Company Benchmark, which include Just Transition elements.

Collaborative initiatives that use leverage to affect change:

-

Climate Action 100+ is an investor-led initiative composed of around 700 investors globally and responsible for over USD 68 trillion in assets under management, which aims to ensure the world’s largest corporate greenhouse gas emitters take action on climate change.

Alternative Models

-

Orsted, the Danish energy company, was once one of the highest emitting energy companies in Europe, due to its coal-fired power and its oil and gas assets. Since 2009 it has undergone a transition to become a global leader in renewable energy, reducing its GHG emissions by 98% (from 2006 levels, scope 1 & 2 only) and aims to be net zero GHG emissions across its value chain (scope 3) by 2040. The company also continues to use its leverage in support of broader systemic transition, in the context of collaborative initiatives, as well as in advocating for the global elimination of fossil fuel subsidies. While there are concerns about the company’s transition strategy, including its 2017 oil and gas divestment (rather than gradual and actively managed decommissioning), this is one of very few examples of a high emitter’s strategic reorientation, with important lessons for other transitioning or soon-to-be transitioning companies.

-

Rivian’s business model distinguishes itself from traditional automakers by focusing exclusively on purpose-built electric vehicles, avoiding reliance on internal combustion engines that drive global greenhouse gas emissions. Its proprietary platform enables efficient production of multiple vehicle models, with efforts to address emissions and social-related risks elsewhere in its value chain. For example, the company is investing in a “supplier park” in close proximity to its Illinois manufacturing facility in order reduce transportation emissions and improve supplier oversight. The company is developing a series of strategic partnerships, including its Amazon electric delivery fleet, to expand market reach.

-

Oatly’s business model is built on replacing dairy with oat-based alternatives, which studies show have 62–78% lower greenhouse gas emissions per liter than cow’s milk. This positions the company as a lower-carbon option in the food sector, even if independent reviews caution that some of the carbon benefits are offset by the impacts from product processing, packaging, and sourcing.

-

In Australia, where the market for “carbon neutral cattle” is growing, farmers are experimenting with carbon neutral cattle systems focused on soil carbon sequestration to offset greenhouse gas emissions, aiming for net-zero emissions from cattle birth to sale.

-

In response to foreign competitive pressures Sweden has developed expertise in niche environmentally friendly steel products and is developing fossil fuel free steel. Such technological innovation is seen as essential to maintaining Swedish competitiveness in the sector.

Other tools and resources

-

Shift (2023) Climate Change & human rights: Avoiding pitfalls for financial institutions

-

Frequently asked questions on Human Rights and Climate Change, Fact Sheet No. 38, United Nations Hunan Rights Office of the High Commissioner, 2021

-

UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights’ Climate Change Hub

-

Amnesty International’s Climate Change Hub

-

BSR (2025) Transforming Business Models: A BSR framework to capture the opportunity of business transformation within planetary boundaries

-

Germanwatch (2018) Guidance on climate risks and human rights in the insurance sector

-

AIM Progress (2025) Bringing people and their rights into corporate climate action

-

Human Level (2024) Navigating the Just Transition: Practical Steps for Business Leaders

-

UN Working Group on the issue of human rights and transnational corporations and other business enterprises (2023) Information Note on Climate Change and the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights provides clear guidance (in section IV) on integrating climate considerations into HRDD.

Citation of research papers and other resources does not constitute an endorsement by Shift of their conclusions.

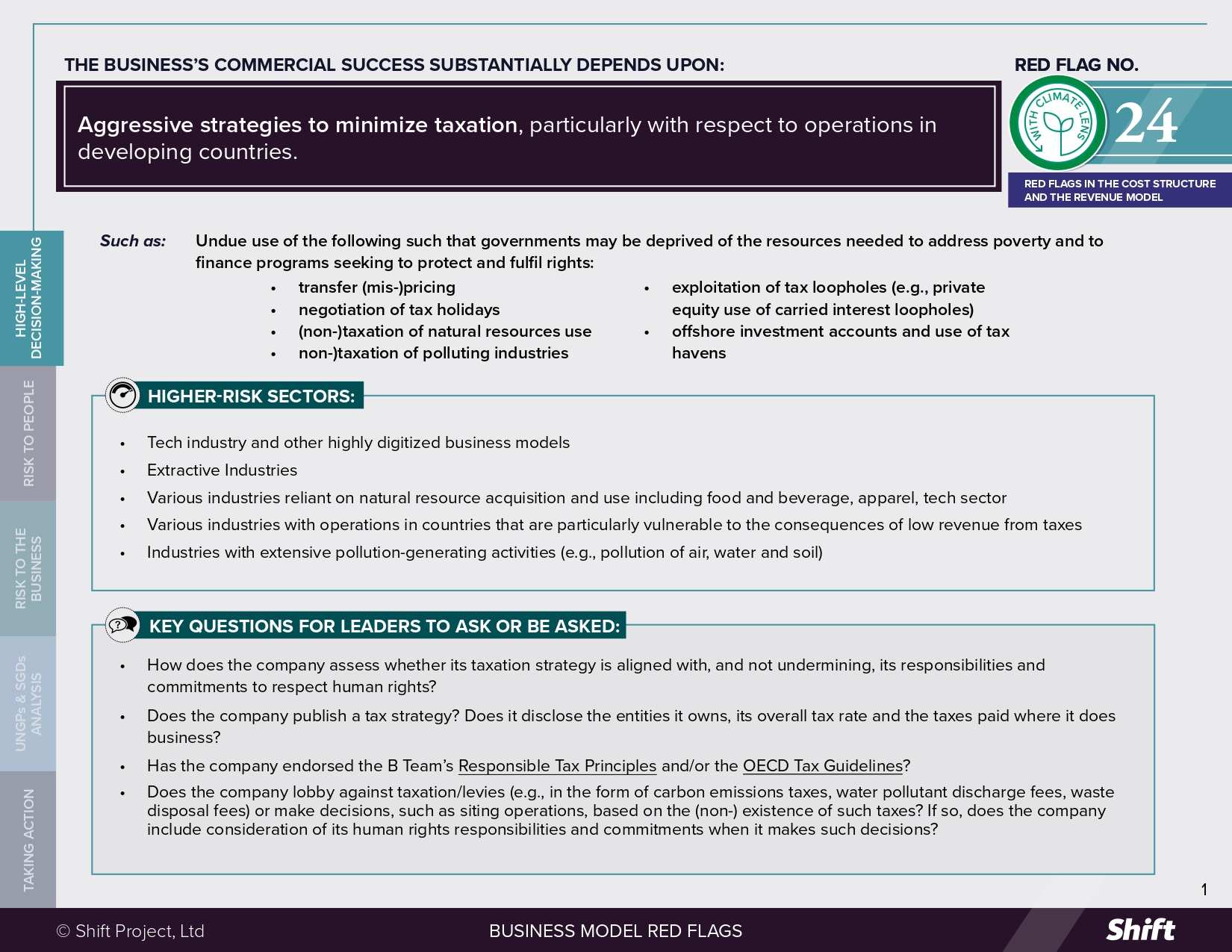

Red Flag 24. Aggressive tax-minimization strategies

RED FLAG # 24

The business’s commercial success substantially depends upon aggressive strategies to minimize taxation, particularly with respect to operations in developing countries.

For Example

Undue use of the following such that governments may be deprived of the resources needed to address poverty and to finance programs seeking to protect and fulfil rights:

- transfer (mis-)pricing

- negotiation of tax holidays

- (non-)taxation of natural resources use

- (non-)taxation of polluting industries

- exploitation of tax loopholes (e.g., private equity use of carried interest loopholes)

- offshore investment accounts and use of tax havens

Higher-Risk Sectors

- The tech industry and other highly digitized business models

- Extractive industries

- Various industries reliant on natural resource acquisition and use including food and beverage, apparel, tech sector

- Various industries with operations in countries that are particularly vulnerable to the consequences of low revenue from taxes

- Industries with extensive pollution-generating activities (e.g., pollution of air, water and soil)

Questions for Leaders

- How does the company assess whether its taxation strategy is aligned with, and not undermining, its responsibilities and commitments to respect human rights?

- Does the company publish a tax strategy? Does it disclose the entities it owns, its overall tax rate and the taxes paid where it does business?

- Has the company endorsed the B Team’s Responsible Tax Principles and/or the OECD Tax Guidelines?

- Does the company lobby against taxation/levies (e.g., in the form of carbon emissions taxes, water pollutant discharge fees, waste disposal fees) or make decisions, such as siting operations, based on the (non-) existence of such taxes? If so, does the company include consideration of its human rights responsibilities and commitments when it makes such decisions?

How to use this resource. ( Click on the “+” sign to expand each section. You can use the side menu to return to the full list of red flags, download this Red Flag as a PDF or share this resource. )

Understanding Risks and Opportunities

Risks to People

|

The International Bar Association’s Human Rights Institute (IBA-HRI) found that in the context of the developing world, tax practices considered most relevant to potential human rights impacts include transfer-pricing and other cross-border intra-group transactions (see L Lipsett). Multi-national enterprises may “take advantage of gaps in the interaction of different tax systems to artificially reduce taxable income or shift profits to low-tax jurisdictions in which little or no economic activity is performed” (see OECD). The Tax Justice Network’s State of Tax Justice 2024 report states that multinational enterprises “are shifting on average USD 1.13 trillion worth of profit into tax havens, causing governments around the world to lose USD294 billion per year in direct tax revenue” and that a further USD145 billion in direct tax revenue is lost from offshore wealth tax evasion. In certain jurisdictions and sectors, this type of “offshoring” can be particularly impactful. For example, several large agro-exporters operating in the Ukraine have registered their grain operations in offshore jurisdictions (e.g. Switzerland, Cyprus, British Virgin Islands). The resulting lost tax revenue for Ukraine is estimated to be USD1.2 billion annually from corn alone between 2012–17, instead of being retained in Ukraine to support domestic services, infrastructure or small-scale farmers, thus contributing to rising inequality in the country and acutely impacting the country’s ability to meet basic domestic needs in a time of war. There are also stark examples where loopholes in country tax codes are exploited significantly to minimize corporate tax liability, with important implications for tax revenues. For example, a 2025 study found that in the United States, private equity managers exploit a carried interest loophole by classifying their share of fund profits—typically around 20%—as long-term capital gains rather than ordinary income, thereby significantly reducing their tax liability. This allows them to pay tax rates of around 20% (plus surcharges), instead of the much higher top income tax rates of 37%. Additionally, these managers defer paying taxes on this income until assets are sold, creating a further timing advantage that contributes to a lower effective tax burden compared to wage earners. Combined, these strategies allow private equity executives to cut their effective tax rate nearly in half, depriving the state of important tax revenue and adding to already high levels of wealth inequality that erode political and social stability (see below). These or similar strategies also exist in other jurisdictions, including the UK. Highly digitized business models have also been associated with challenges to existing taxation frameworks, including where the business is highly involved in the economic life of a jurisdiction without any significant physical presence, as well as where a high number of assets are intangible (such as algorithms and software). (See OECD). Aggressive taxation practices such as those identified above can “deprive governments of the resources required to provide the programmes that give effect to economic, social and cultural rights, and to create and strengthen the institutions that uphold civil and political rights.” (See Lipsett). Lost revenue from taxation can lead to decreased funds available for spending on “services such as health, education, housing, access to water and other human rights.” It has been reported that countries in the global south lose much more money to tax evasion and illicit financial flows than they receive in international aid. The Tax Justice Network estimates that lower income countries lose five times as much tax income, as a share of their public health budgets, compared to higher income countries.

To remedy climate-related loss and damage incurred by vulnerable communities globally. Amnesty International and others have called for funding from public sources, “including through taxes and levies for corporations and sectors based on the polluter pays principle.” Another way in which tax and the low carbon transition intersect is with respect to the use of carbon pricing schemes to curb emissions from high-carbon industry. These tax policy approaches are in use in more than 25 jurisdictions globally, and if progressive in their design, can minimize impacts on households while helping to raise revenue for health, education, jobs, low-carbon industries, climate resilient infrastructure and enhancing energy access. These revenues can be used to ensure that the climate transition occurs in a way that respects the rights of workers and communities and serve to “complement, rather than compromise, other efforts of States to fulfill their human rights obligations”. However, corporate lobbying in opposition to this type of taxation has tended to focus on characterizing it as unfair and punitive for workers and consumers regardless of steps taken to minimize regressive impacts. This characterization has, in some instances, helped to undermine both the revenue generation and emissions reduction potential of carbon pricing. Examination of corporate lobbying on tax issues should reflect consideration of the full range of effects on people and not make selective arguments. |

Risks to the Business

-

Reputational Risks:

-

“Over recent years, the tax affairs of major businesses have been subject to unprecedented levels of scrutiny, debate and controversy.” The FT, has noted that despite the “dry, complex nature of corporate tax planning,” campaigners have begun to focus on the issues with “zeal.”

-

In Canada, a Canada Revenue Agency investigation into KPMG’s role in facilitating an offshore tax avoidance scheme to help wealthy individuals avoid taxes, has contributed to ongoing reputational issues for KPMG in Canada, legal challenges, public and professional scrutiny, regulatory penalties and investigations into KPMG’s corporate practices.

-

-

Regulatory Risks: Concerns over the facilitation of base erosion and profit shifting through uneven legislation has led to a multilateral international tax policy initiative under the OECD, resulting in several actions including: a multilateral treaty, the sharing of information between tax administrations, significantly enhanced transparency and exchange of information on tax rulings and annual monitoring and review of harmful tax practices, which has, as of February 2025, resulted in the abolition of 126 tax regimes, with an additional eight in the process of being abolished. International action such as this can be expected to draw regulatory attention across different jurisdictions to aggressive corporate tax practices.

Operational Risks:

-

Public outcry over taxation inequality has

“contributed to significant political instability in many developing countries” which has also been to the detriment of companies operating in these areas. Such outcry has not been limited to developing countries: in the UK several companies have appeared before the Public Accounts Committee or had their high street stores occupied by protestors, and US companies have been the subject of major news investigations. -

Legal, Financial and Operational Risks:

-

In 2024, after several years of legal proceedings, Apple lost its last appeal in the European Court of Justice to avoid paying $14.34 billion (13 billion euro) in back taxes to Ireland, due to “unfair and preferential tax schemes” that it was found to have benefitted from in that jurisdiction.

-

What the UN Guiding Principles say

|

The “corporate responsibility to respect,” the second pillar of the UNGPs, “exists independently of States’ abilities and/or willingness to fulfil their own human rights obligations, and … exists over and above compliance with national laws and regulations protecting human rights.” (Principle 11, Commentary). In other words, “all business enterprises have the same responsibility to respect human rights wherever they operate” (Principle 23, Commentary), whether or not they have a domestic legal obligation to do so. As such, undue or aggressive use of taxation strategies may infringe companies’ responsibility even where actions are legal under local taxation laws. The UNGPs note that companies should “strive for coherence between their responsibility to respect human rights and policies and procedures that govern their wider business activities …” (Principle 16, Commentary), which would be relevant where aggressive tax strategies undermine efforts to respect rights in jurisdictions of operation. Where a company is benefiting from an unduly aggressive tax strategy or unusually generous taxation deal in a particular location, it may be directly linked to impacts that result from a lack of public services for local populations. Where it is aware of this situation and does nothing, it may be judged to contribute to such impacts. This may be a contribution in parallel with other companies benefiting from similar tax arrangements, such that they collectively deplete state revenues needed to fulfil people’s human rights. If the company lobbies in favor of tax deals that undercut state revenues with similar results, it may be seen as contributing by incentivizing the government to favor corporate benefits over the human rights of the population. The connection between taxation planning and human rights is complex, but receiving increased attention. Mauricio Lazala, Deputy Director of the Business and Human Rights Resource Centre has noted that “[t]he State duty to protect human rights in its corporate tax policies, the business responsibility to respect human rights and carry out due diligence in their tax practices, and the need for effective remedy for tax abuse are all relevant, yet still emerging dimensions of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.” |

Possiblr Contributions to the SDGs

Taxation policy is a key element in facilitating the achievement of the SDGs. As such, this red flag indicator is relevant for a range of SDGs, including:

-

SDG 1: No Poverty, including

-

Target 1.2: By 2030, reduce at least by half the proportion of men, women and children of all ages living in poverty in all its dimensions according to national definitions

-

-

SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities, in particular

-

Target 10.4: Adopt policies, especially fiscal, wage and social protection policies, and progressively achieve greater equality. Income redistribution through taxation can contribute to reducing inequality and promoting inclusive growth.

-

-

SDG 13: Climate Action, in particular

-

Target 13.1: Strengthen resilience and adaptive capacity to climate-related disasters

-

Target 13.4: Implement the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change

-

-

SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals, in particular

-

Target 17.1: Strengthen domestic resource mobilization, including through international support to developing countries, to improve domestic capacity for tax and other revenue collection

-

Taking Action

Due Diligence Lines of Inquiry

-

Do we have a policy on tax planning that includes a human rights perspective? Do we have a considered and disclosed position on use of “tax havens”?

-

How transparent are we about our taxation strategy including as regards our operations in developing countries? Do we disclose how our approach to taxation planning aligns with our business purpose and sustainability strategy?

-

To what extent do we review the structures and practices of tax planning through the lens of our responsibility respect human rights, (rather than merely the amount of tax paid, which is an outcome of these practices).

-

Are we involved in projects for which tax rules are being created? Is our approach to these negotiations aligned with our sustainability commitments/ responsibilities?

-

How meaningful is the interaction between our departments and external advisors responsible for taxation strategy and our corporate responsibility/ sustainability/human rights teams, with a view to internal alignment?

Mitigation Examples

* Mitigation examples are current or historical examples for reference, but do not offer insight into their relative maturity or effectiveness.

-

The Fair Tax Mark is a scheme that certifies a business’ tax conduct, including that it “seeks to follow the spirit, as well as the letter of the law, shuns corporate tax avoidance such as the artificial use of tax havens, and is transparent about profits made and taxes paid.”

-

In 2024, the Fair Tax Foundation and CSR Europe teamed up to launch the Tax Responsibility and Transparency Index, which is a benchmark that evaluates company tax performance across five areas: policy and strategy; management and governance; stakeholder engagement; transparency and reporting; and contribution and narrative.

-

Ørsted was the first Danish multinational to receive the Fair Tax Mark and it is a founding member of the Tax Responsibility & Transparency Index. Økonomisk Ugebrev, a Danish financial publication, also ranked it highly in tax transparency, based on their country-by-country reporting, disclosure on tax havens and governance practices.

-

The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) is a coalition of governments, companies and civil society working “to improve openness and accountable management of revenues from natural resources.”

-

Allianz states that it “seeks to be a responsible taxpayer…”. The company reports that it does “not engage in aggressive tax planning or artificial structuring that lacks business purpose or economic substance,” does not use tax havens and “refrain[s] from discretionary tax arrangements.” Allianz has a comprehensive “Standard for Tax Management” which requires that tax planning be based on valid business reasons.

-

A number of companies are annually publishing country by country tax reports to bring greater transparency to their tax activities, including Unilever, BHP and Maersk.

-

In addition to an annual country by country tax report, Danone opines on how its tax practices align with its broader sustainability objectives and discloses its activities in particular jurisdictions that may be perceived as tax havens.

Alternative Models

-

In 2012 Starbucks announced that following “loud and clear” messages from customers, the company would make “changes which will result in Starbucks paying higher corporation tax in the UK – above what is currently required by law”.

-

The 1% for the Planet initiative applies a 1% tax on annual corporate sales, which members commit to donating to grassroots environmental organizations.

-

The Global Green New Deal, which is a declaration signed onto by 300 politicians across 44 jurisdictions, calls for several actions including working together to regulate illicit financial flows, stop capital flight, end tax havens and ensure that world’s biggest corporations and wealthiest people pay their fair share of tax.

Other Tools and Resources

-

The B Team’s Responsible Tax Principles were developed through dialogue with a group of leading companies, convened by The B Team with contributions from civil society, institutional investors and international institution representatives.

-

The Center for Economic and Social Rights has developed a set of Principles for Human Rights in Fiscal Policy, which are derived from international human rights law, including soft law.

-

Tax Justice Network is a UK-based international research and advocacy network focusing on the link between taxation and, inter alia, human rights. It publishes the Corporate Tax Haven Index and has published deep dives into the links between climate justice and tax justice, including specific sectoral analysis for shipping and extractive sectors.

-

The Tax Responsibility and Transparency Index enables multinational businesses to benchmark themselves against high-bar civil society frameworks, pending legislation and pioneering companies in five key areas of tax conduct.

-

The International Bar Association’s Human Rights Institute released a 2013 report entitled Tax Abuses, Poverty and Human Rights. The Report addresses tax abuses from the novel perspective of human rights law and policy. It is based on extensive consultation from diverse perspectives and offers insight into the links between tax abuses, poverty and human rights.

-

The Business and Human Rights Resource Centre portal on Tax Avoidance.

-

Oxfam (2017) Making Tax Vanish: How the practices of consumer goods MNC RB show that the international tax system is broken. Contains an in-depth analysis and critique of the taxation planning practices of one company as well as the company’s response.

-

M Lazala, Business & Human Rights Resource Centre (2015) Tax avoidance: the missing link in business & human rights?

-

The OECD’s Tax portal includes its Action Plan on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting and Inclusive Framework.

Citation of research papers and other resources does not constitute an endorsement by Shift of their conclusions.

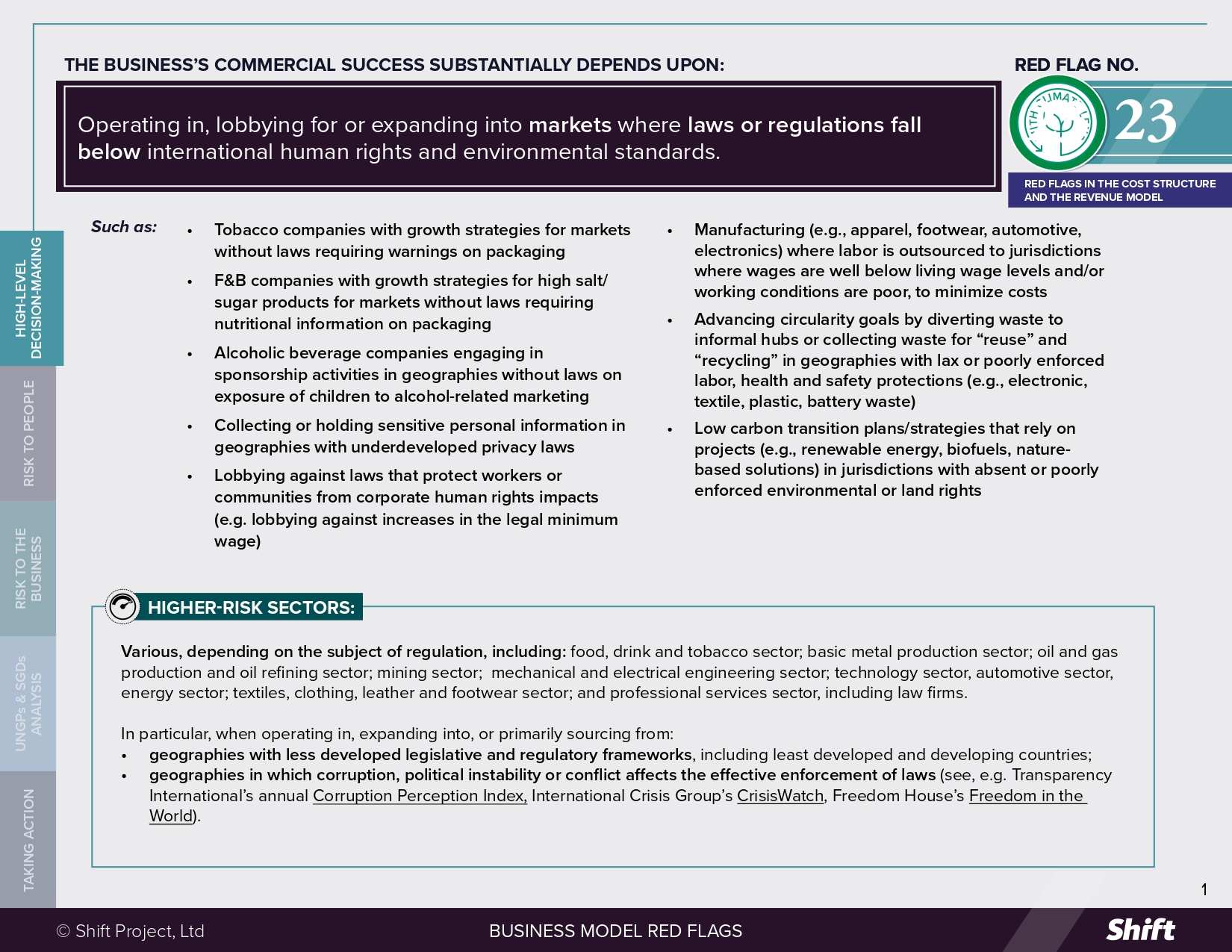

Red Flag 23. Markets where regulations fall below human rights standards

RED FLAG # 23

The business’s commercial success substantially depends upon: operating in, lobbying for or expanding into markets where laws or regulations fall below international human rights and environmental standards

For Example

- Tobacco companies with growth strategies for markets without laws requiring warnings on packaging

- Food and beverage companies with growth strategies for high salt/ sugar products for markets without laws requiring nutritional information on packaging

- Alcoholic beverage companies engaging in sponsorship activities in geographies without laws on exposure of children to alcohol-related marketing

- Collecting or holding sensitive personal information in geographies with underdeveloped privacy laws

- Lobbying against laws that protect workers or communities from corporate human rights impacts (e.g. lobbying against increases in the legal minimum wage)

- Manufacturing (e.g., apparel, footwear, automotive, electronics) where labor is outsourced to jurisdictions where wages are well below living wage levels and/or working conditions are poor, to minimize costs

- Advancing circularity goals by diverting waste to informal hubs or collecting waste for “reuse” and “recycling” in geographies with lax or poorly enforced labor, health and safety protections (e.g., electronic, textile, plastic, battery waste)

- Low carbon transition plans/strategies that rely on projects (e.g., renewable energy, biofuels, nature-based solutions) in jurisdictions with absent or poorly enforced environmental or land rights

Higher-Risk Sectors

Various, depending on the subject of regulation, including: food, drink and tobacco sector; basic metal production sector; oil and gas production and oil refining sector; mining sector; mechanical and electrical engineering sector; technology sector, automotive sector, energy sector; textiles, clothing, leather and footwear sector; and professional services sector, including law firms.

In particular, when operating in, expanding into, or primarily sourcing from:

- geographies with less developed legislative and regulatory frameworks, including least developed and developing countries;

- geographies in which corruption, political instability or conflict affects the effective enforcement of laws (see, e.g. Transparency International’s annual Corruption Perception Index, International Crisis Group’s CrisisWatch, Freedom House’s Freedom in the World).

Questions for Leaders

- Has the company assessed whether its climate strategies – including its climate transition or circular economy strategies – could succeed without any reliance on these gaps in legal frameworks?

- Where impacts on people connected to the business arise in a geography of manufacture or sourcing, does the company undertake a root cause analysis and seek to understand whether and how the company’s business model creates a reliance on, e.g. labor/wage conditions that give rise to these risks?

- How does the company explain applying different standards related to human rights and the environment in different jurisdictions?

- How does the company know whether its lobbying activities on regulation are aligned with human rights principles, policies and commitments and consistent across functions and locations?

- Has the company ever supported new regulations relevant to human rights or health protections in its sector or operations?

- How has the company assessed whether the regulations it has opposed would have helped improve informed choice and/ or human rights, and how and to whom does it explain its conclusions?

How to use this resource. ( Click on the “+” sign to expand each section. You can use the side menu to return to the full list of red flags, download this Red Flag as a PDF or share this resource. )

Understanding Risks and Opportunities

Risks to People

Where companies operate in or source responsibly from non-home markets, they can be a catalyst for growth and prosperity. However, where the business model is substantially dependent on gaps in legal frameworks that may not exist in their home market, the company can be seen to be exploiting these governance gaps at this risk of impacts on people:

“The root cause of the business and human rights predicament today lies in the governance gaps created by globalization -between the scope and impact of economic forces and actors, and the capacity of societies to manage their adverse consequences. These governance gaps provide the permissive environment for wrongful acts by companies …”

— Protect, Respect and Remedy: A Framework for Business and Human Rights, UN Doc A/HRC/8/5 (7 April 2008)

Companies exploiting such gaps may engage in:

-

Practices associated with maintaining this business model feature risk perpetuating a “race to the bottom,” as countries compete with lower regulatory standards to attract corporate investment.

-

This may manifest, for example, with the siting and re-siting of operations or sourcing in locations with no or low minimum wages or inadequate labor or environmental protections, affecting peoples’ right to health, right to a family life, right not to be subjected to forced labor and numerous other impacts. The impact on individuals working for suppliers of foreign brands in geographies where legal protections are weaker has been well documented, including for examples in this study of Female Migrant Workers in Bangalore’s Garment Industry. Other examples include siting call centres in jurisdictions with underdeveloped overtime laws and worker protections; sourcing electronics from jurisdictions with weaker migrant workers protections or collective bargaining protections; or moving factories over borders where there is weak enforcement of labor standards.

-

In its 2015 report, Human Rights Watch documented how Cambodia’s rise as a garment manufacturing hub was enabled by low wages and favorable trade conditions, but sustained in part through systemic labor rights abuses. The report discusses widespread use of short-term contracts to discourage organizing, failure to enforce labor laws, suppression of independent unions, and impunity for abusive practices—all of which helped maintain Cambodia’s competitive position in global supply chains, attracting foreign business.

-

-

Lobbying against measures or laws that protect people from human rights impacts, for example lobbying against:

-

(increased) minimum wage laws, affecting among other things, the right to just and favorable conditions of work, including decent remuneration;

-

Indigenous title to land affecting Indigenous Peoples’ rights;

-

restrictions on emissions into land, sea and air, affecting the right to an adequate standard of living and to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment;

-

laws that support informed choice or plain packaging/non-marketing of harmful products such as cigarettes, affecting the right to health.

-

-

Legal strategies that prevent the state from protecting people from human rights impacts (potentially various), for example:

-

seeking to use investment treaties (including stabilization clauses) and closed arbitration processes to limit states’ abilities to enact or amend legislation or regulations that increase human rights protection;

-

seeking to enforce intellectual property rights against public health imperatives.

-

- Climate transition or circular economy strategies that hinge on exploitative land/resource use, where there are no, or poorly enforced, labor/environmental laws or informal labor arrangements, for example:

- land acquisition/use to facilitate renewable energy or biofuel cultivation in geographies where land ownership or resource use may be contested, with implications for Indigenous Peoples’ and community land rights, as well as human rights defenders (see also Red Flag 12)

-

transitioning from sourcing fossil fuels to sourcing biomass for electricity generation without measures to address health and social impacts disproportionately experienced by “poor, Black and rural communities in the South” (see also Red Flag 13)

-

relying on informal labor in recycling hubs (e.g., for EV battery component recovery) or other waste recovery/collection operations (e.g., “waste pickers”) in geographies with absent or poorly enforced labor laws and hazardous working conditions (see also Red Flags 17 and 18)

-

sourcing critical minerals (e.g., cobalt, copper, lithium) or other primary materials (e.g., polysilicon and rare earth elements) needed for low carbon and digitalization technologies from operations linked to child or forced labor, unsafe working conditions and local environmental degradation (see also Red Flag 14)

-

relying disproportionately on nature-based solutions or carbon offset projects located in jurisdictions with poor or poorly enforced laws and regulations around land, labor and Indigenous Peoples, resulting in negative impacts on workers and communities (see also Red Flag 14)

Risks to the business

-

Reputational and operational: Risks arise due to inconsistencies between what the company says in public and in private regarding regulatory protections, and in what it does in different parts of the world based on different levels of regulatory protection. Reputations may also be open to attack where the company invests considerable resources in weakening human rights or environmental protections. Some examples of where these types of risks have arisen include:

-

Kellogg’s attracted negative attention when it sued the Mexican government over a labelling policy requiring food manufacturers to include warning labels on the front of any boxes they sell in Mexico to educate consumers on excess sugar and fat. Similarly in the USA in 2023, major food manufacturers including General Mills, Kellogg’s, Conagra, and trade bodies like the Consumer Brands Association strongly opposed updated FDA proposals restricting the “healthy” label for foods high in added sugars, sodium, or fats. They argued the rules violated First Amendment rights and unfairly targeted nutrient-dense foods. Media highlighted that corporate claims were “drawing on big tobacco’s playbook,” with critics pushing back on potential conflicts of interest and misalignment with public health goals.

-

The Guardian reported on a leaked email sent by a senior executive from Philip Morris International regarding their lobbying plans to counter the World Health Organization’s efforts to crack down on vaping by young people and further smoking restrictions.

-

The Association of Convenience Stores (ACS), which includes major UK supermarkets like Sainsbury’s and Asda, has lobbied UK MPs to weaken or block a planned ban on disposable vapes, which aims to address the negative health impacts of disposables for young people and other vulnerable users. Public health groups have again argued that this behavior is “straight from the playbook of Big Tobacco”.

-

Reputational, regulatory and financial risks:

- As part of its climate change strategy, Drax Group transitioned from a coal-fired power generator into Europe’s largest biomass energy producer. In lieu of coal, the company now sources and burns wood pellets—often from mature forests in the U.S. and Canada. Advocates from civil society organizations (CSOs) have argued that the mills that process these pellets are disproportionately located in low-income, predominantly Black communities, where emissions of particulate matter and VOCs have been linked to respiratory illness. As a result, the company has faced reputational impacts (it is the subject of several CSO campaigns, such as StopBurningTrees.org, BankTrack, Just Transition Wakefield), regulatory action (in 2021, one of their US-based wood pellet facilities faced a USD2.5 million air pollution fine) and been dropped from sustainable investment indices. The company is also the subject of regulatory scrutiny, as they continue to lobby with the objective of influencing the UK’s renewable energy regulatory support program in their interests.

Legal and financial risk:

- Where a company mounts an unsuccessful legal challenge to government regulation aimed at public protection, it may face financial penalties, as in the case of tobacco company Philip Morris International, which was ordered to pay the Australian government millions of dollars after unsuccessfully suing the nation over its plain-packaging laws.

- A Florida court ordered Chiquita Brands International to pay $38 million to the families of eight men that were murdered by paramilitary forces financed by the company to facilitate their operations in Colombia in the absence of local law enforcement capabilities, which company executives cited as “the cost of doing business in Colombia”.

- Meta has faced civil society scrutiny, as well as a $150 billion class-action lawsuit and a U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission whistleblower complaint related to the platform’s expansion into Myanmar, where it has been accused of playing a pivotal role in the dissemination of hate speech that fueled violence against the Rohingya people. The accusations tie back to their alleged exploitation of weak governance and institutions.

- Financial risks: can arise where investors consider companies’ attempts to influence public policy in their investment decisions. For example:

-

US-based Trillium Asset Management reportedly monitors the levels and recipients of corporate giving, corporate policies on political contributions and membership of industry (lobbying) associations as part of their background research for stock selection in their socially responsible investment funds.

-

In 2022, Netflix’s shareholders approved a proposal on enhanced lobbying disclosure and oversight (garnering 60% support from the company’s shareholders) led by Boston Common Asset Management.

-

During the 2021 shareholder voting season, a series of shareholder proposals seeking stronger disclosure of how a company’s climate lobbying aligns with the Paris Agreement won majority votes from the shareholders of Delta Air Lines, Phillips66, Norfolk Southern Corp, ExxonMobil, and United Airlines. Further, a shareholder resolution against Nippon Steel Corporation in June 2024 seeking enhanced transparency on lobbying expenditures and positions garnered nearly 30% of the shareholder vote indicating growing concern of this issue in Asia. (see also Red Flag 25)

-

What the UN Guiding principles say

Under the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, the corporate responsibility to respect human rights “exists independently of States’ abilities and/or willingness to fulfil their own human rights obligations, and … exists over and above compliance with national laws and regulations protecting human rights” (Principle 11, Commentary). In other words, “all business enterprises have the same responsibility to respect human rights wherever they operate” (Principle 23, Commentary), whether or not they have a domestic legal obligation to do so. As such, adopting an inherently uneven, compliance-based approach risks breaching the company’s responsibility in places where laws do not meet internationally accepted human rights standards.

The UNGPs note that companies should, “strive for coherence between their responsibility to respect human rights and policies and procedures that govern their wider business activities and relationships [including] …. lobbying activities where human rights are at stake” (Principle 16, Commentary).

Where the company actively lobbies against or takes action to constrain laws that have the practical effect of furthering respect for human rights, it risks contributing to human rights impacts, whether as a sole contributor or as a result of the aggregate contribution of several actors.

Where a company is benefiting from an absence of protection of rights in the countries where it operates, it may be directly linked to impacts; where it is aware of this and does nothing, it may, depending on a number of factors, be considered to be contributing to the impacts.

Possible Contributions to the SDGs

Addressing impacts on people associated with this red flag indicator can contribute to a range of SDGs depending on the impact concerned, for example:

-

SDG 3: No poverty, in particular Target 3.5: strengthen the prevention and treatment of substance abuse, including narcotic drug abuse and harmful use of alcohol; and Target 3.10: strengthen the implementation of the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control in all countries, as appropriate.

-

SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth, in particular Target 8.5: by 2030, achieve full and productive employment and decent work for all women and men, including for young people and persons with disabilities, and equal pay for work of equal value.

-

SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production, in particular Target 12.2: Sustainable Management and Use of Natural Resources and Target 12.5: by 2030, substantially reduce waste generation through prevention, reduction, recycling and reuse.

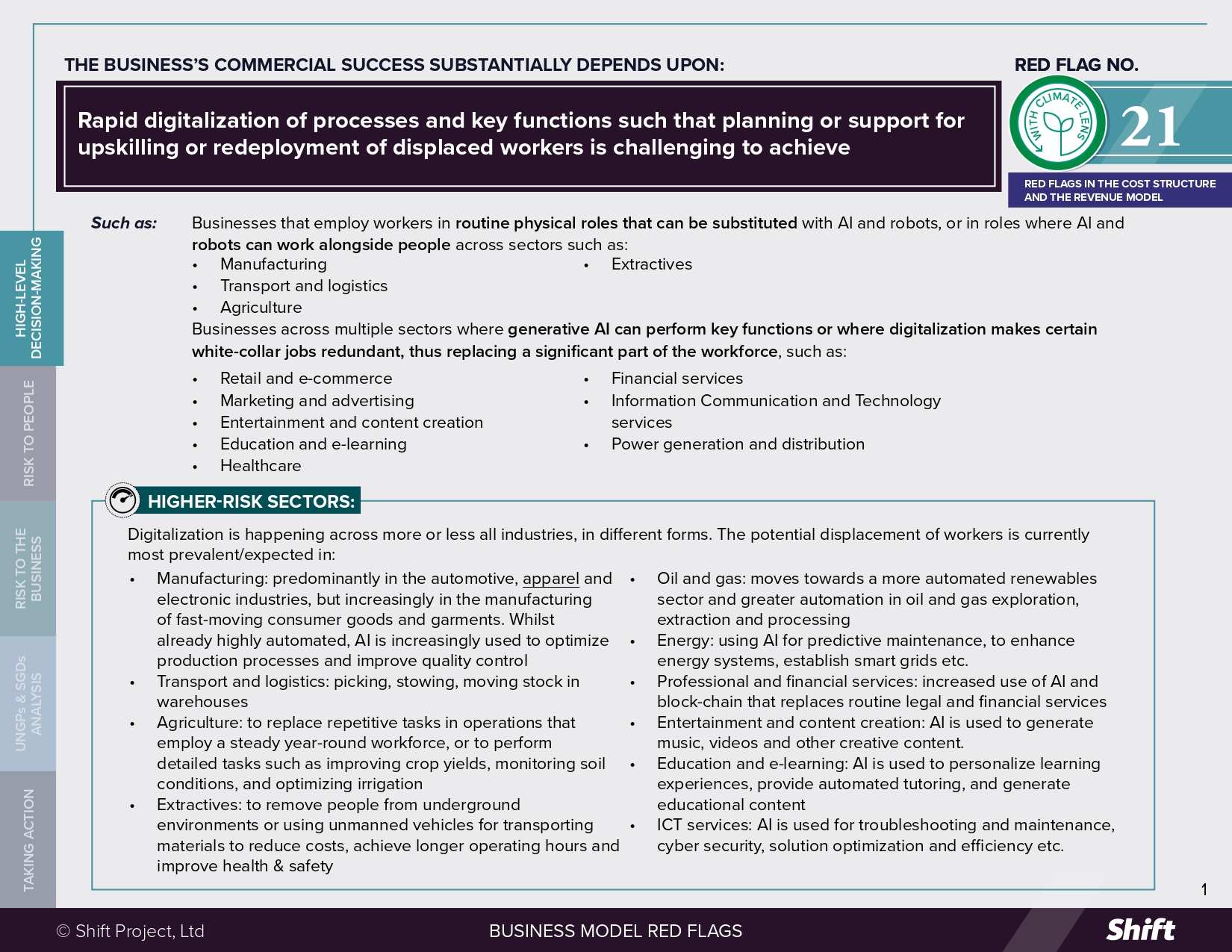

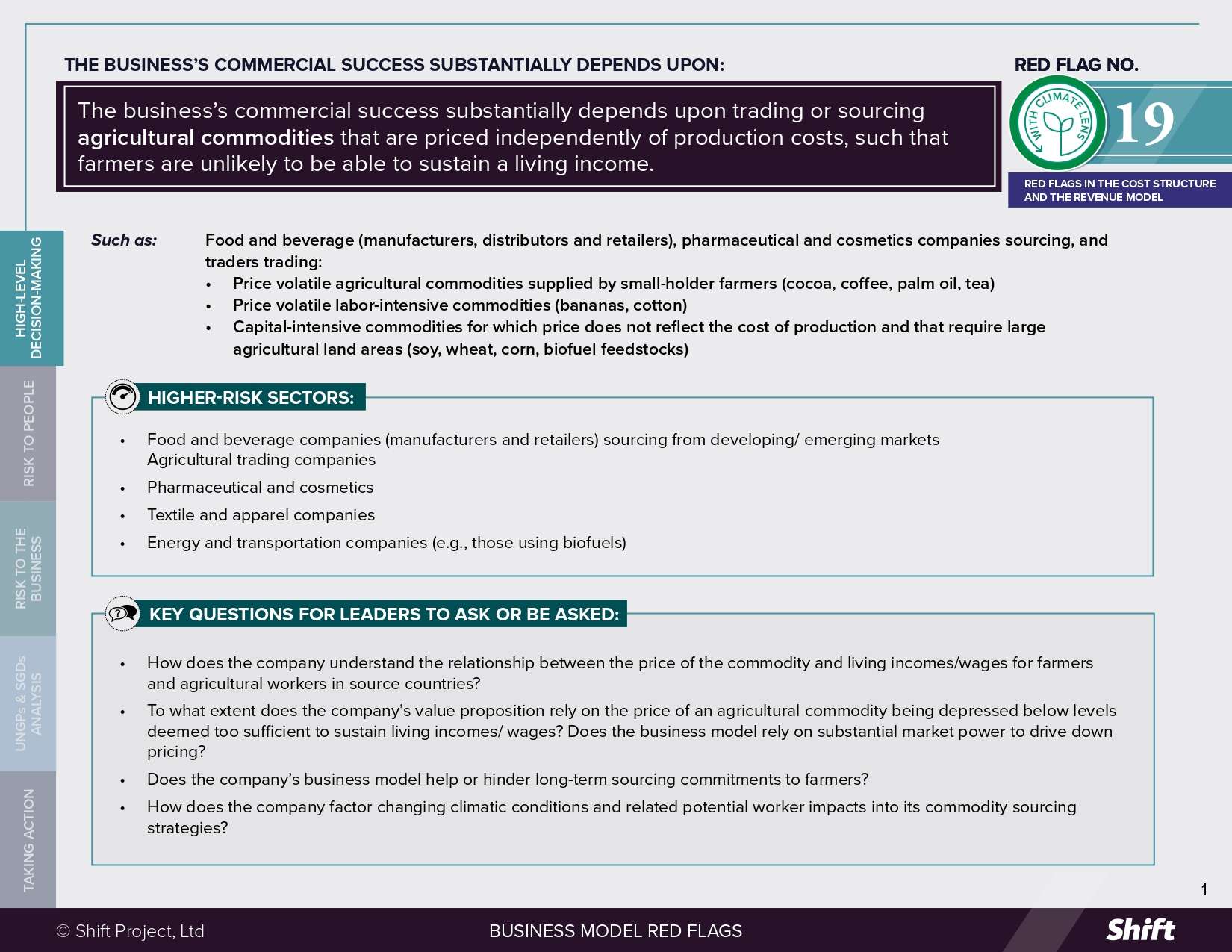

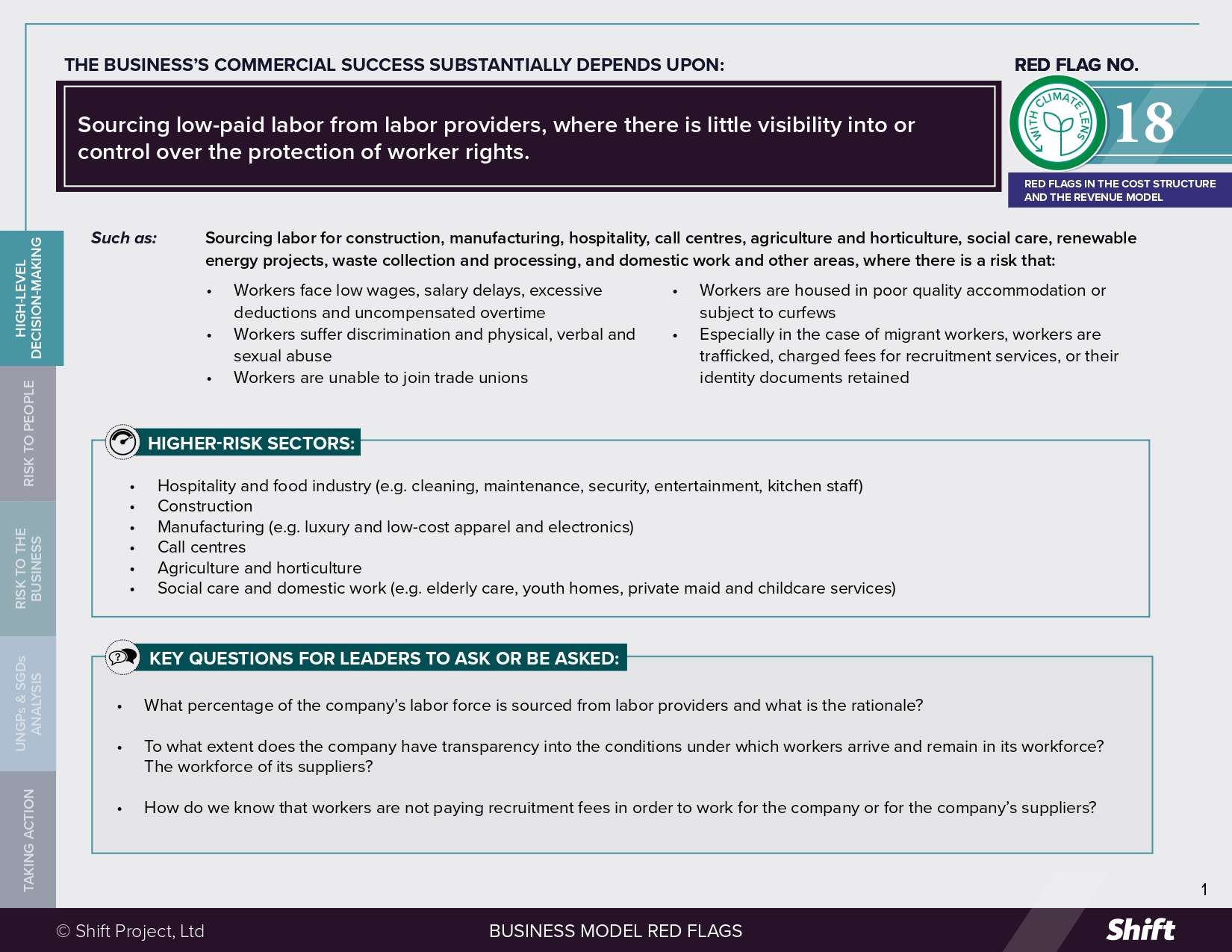

-